Читать книгу Strange Paradise - Grace Schulman - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhen it came to marriage, I could delay Jerry no longer than two years. “Look, we are married in every way. Why not make it official? We’ll work, strum, walk, fight. Same difference,” he declared one day. I loved him but still feared the confines of wedded life. Freedom, my mother had taught, was the highest choice, never to be endangered. Jerry had a direction in his work, while I was still seeking one.

I needed to think. In a cold February, in 1959, I packed a small bag, put on a winter coat, and left for Barcelona with thirty dollars in my wallet, enough to cover a five-night stay in a rooming house just a short walk from Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia church. Without unpacking, I went to a park nearby and sat on a bench alone. Musicians were playing wooden flutes. Soon a crowd gathered and formed a circle. Hands were everywhere, and feet stepped to the sardana, a local folk dance. I joined the dance, amiable people inviting me into their ring. With each turn I felt free—but with each counter-turn I wished that Jerry were dancing there with me. I came home resolved never to leave him. And finally, when I returned home he convinced me that by marriage he meant not a protective shelter—not a house, not even a tent, but a common path through dense trees.

I would change my name to his, Grace Waldman to Grace Schulman. The loss was chilling: would I lose my self just as I was seeking it? But I knew it would have confused employers, registrars, and professors in an age unused to wives with maiden names. The only time I tried being a wife named Grace Waldman, I was met with a baffled stare: “Do you mean you married a Waldman?”

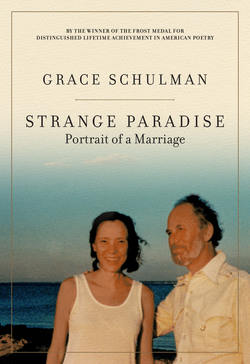

We were wed at the Plaza Hotel on September 6, 1959. I was twenty-seven to his thirty-two. His parents, Conservative Jews, had to adjust to our Reform wedding, with no canopy and no bridal veil. His mother had assumed that the groom would ritually step on a glass, but our Rabbi Bamberger discouraged it: “We don’t know the exact reason for it, and the breakage could be dangerous.” His parents did, however, compliment the rabbi on his address, which emphasized the separateness inherent in a good marriage. Jerry’s brother, Edward, flew in from Boston to be best man. With him was his wife, Beatrice, large with her second child. My mother helped me pick out a silky beige dress. She herself wore an outsize blue one, my father fearing she would look too sexy if she wore her true size. I was marrying the man I loved, and Jerry was beaming. In other words, a perfect day.

Why then did I pace the dressing room and down four cups of strong black coffee?

I’m stricken with terror. And what am I doing now? What if I lose my freedom? What if it doesn’t work? What would that do to my grandmother? Surely a divorce would give her cause for vast concern. Step back, now: what if he is summoned to a lab in Texas? What would I do there? My father smiles reassuringly as he walks me down the aisle, but my hands are shaking. The bridesmaid, my cousin Katie, is shooting me a doubtful glance. The makeshift altar is raised too high on too steep a platform. I can’t see the rabbi, let alone climb up to where he stands. My white rose bouquet has wilted. The rabbi speaks mostly in English, but his few Hebrew words seem an admonition for me to be as loyal as Ruth to my mother-in-law. The pianist is playing funereal music. The tradition calls forth high moral standards, the prayers assuming spotless behavior, and I think we might not come up to the mark.

Responding to my voice, which quivered as we exchanged vows, Jerry felt that what we needed was freedom. After the reception, we sank into the Austin-Healey and drove far into upstate New York. We had no itinerary, no reservations. We’d forgotten it was Labor Day, and hotel vacancies were scarce. Around midnight we found a room, though we had to sleep in separate beds. No matter. Whatever the inconvenience, we were glad to have done it off the cuff.