Читать книгу Strange Paradise - Grace Schulman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

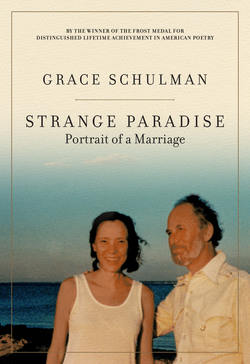

ОглавлениеWhen Alan Gilbert raised his baton at Avery Fisher Hall on November 30, 2013, I slid forward in my seat. Mozart’s Symphony No. 41, the “Jupiter.” We’d heard it before, Jerry and I, in our fifty-four-year marriage, but each time it told us something new. During the intermission, Jerry spoke of the percussion rumblings, the silvery harmonics, the magic. “It was the fire of his last years,” he said, having read that it was composed only three years before Mozart’s death. When the concert was over, I stood with the crowd for an ovation. Jerry couldn’t stand. Sidestepping out of our row, I retrieved his folding wheelchair to push him up the aisle, and we waited downstairs for a hired car that would take us home. I knew he was in pain.

Ironically, it was his long, fast stride that I remembered from when we first met, in Washington Square Park. I hadn’t expected to go to there that Sunday, wanting instead to stay in and get to know the studio apartment I had just rented, for eighty dollars a month plus electric, in a gangly twenty-two-story brick building on University Place, in Greenwich Village. I left my new home only when one of the maintenance workers who’d helped me move chairs in, a burly man from Jamaica given to humming fragments of gospel songs, said I needed air. That day, noticing my guitar balanced precariously on top of a stack of china cups, he directed me to the park, diagonally across the street from my building, where, he said, slowly and with emphasis, “You can play in the fountain.”

I was astonished. What he called the fountain was a limestone circle in the center of the park which, when dry, was brimming with another kind of energy. Faces, crowds of animated faces, people, like me, in their mid-twenties, were singing out “Wimoweh” and “Suliram” and “Down by the Riverside” (with its refrain, “Study war no more”), as though their fervor alone could achieve peace on earth. Nineteen fifty-seven was a year of innocent hope, and these believers rallied, unaware that their dreams would be dashed in the following decade.

In the pre-beatnik fifties, folksingers John Jacob Niles and Susan Reed were the progenitors of Bob Dylan and the Beatles. Alan Lomax and his father, John, hunted work songs and prison chants in America, then collected ballads abroad. Their followers, the fountain singers, were wearing torn jeans and plaid shirts, their Sunday-in-the-park clothes, although I’d seen one of the men that Friday dressed in tweeds for his job.

Sometimes the singers performed individually. A woman on the far ledge offered a bluegrass song from her native Kentucky, accompanied by, she announced, a dulcimer plucked with a turkey quill. Her abiding influence was Jean Ritchie, who gathered Appalachian songs and popularized the dulcimer. Playing an English sea chantey on a guitar was a man I recognized from a news photo as Israel (Izzy) Young, who ran the Folklore Center on nearby MacDougal Street. Izzy was an activist whose only cause was fighting the frequent neighborhood bans on outdoor music. I spoke with him long enough to learn that the actor Theodore Bikel often tried out Austrian ballads here, even before he performed Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Edelweiss” in The Sound of Music on Broadway.

In that stone ambiance on a cool September late afternoon, I sat strumming the guitar my father had bought for me while I was a student at Bard College five years before. Raised on West Eighty-Sixth Street in Manhattan, I was singing a rural Scotch-Irish ballad whose origin was far from mine. It began, “She was a lass from the low country.” I was trying not to look at the man with cropped auburn hair who was sitting on the fountain rim next to me and did not sing. He seemed a few years older than the musicians around him, but he had a boy’s gaze and a youthful way of waving his long arms. I was drawn to his hazel eyes, alert, then darting, which shone when his smile made creases at their corners. Because he did not meet my eyes, I thought he was listening to others, not to me. I was wrong.

We didn’t speak. “Venga Jaleo,” “Röslein,” and “Green-sleeves” went by, our glances still wandering around or beyond each other. I had been informed that it was illegal to sing after six o’clock, and invited some twenty folksingers to my apartment across the Square. A guitarist who enunciated Romanian lullabies thought that the man with cropped auburn hair and hazel eyes was with a pretty young woman nearby, and, with my permission, asked the man to join us. The man wasn’t with anyone.

Back at my place, “Michael, Row,” a spiritual, started up, to the dismay of neighbors objecting to noise. Still the man was silent. (I didn’t know at the time that his behavior was characteristic: he would say, years later, “Silence is the supreme contribution to conversation.”) That night he left early, having surreptitiously copied the number on my telephone. He dialed it within an hour, announced his name, Jerry Schulman, and said in a low, unassuming voice that friends had left him theater tickets to West Side Story the next evening and would I join him. When I accepted he asked me to be ready at six and said we’d travel uptown together. The lie was transparent—though charming: the next night was a Monday, with its interval between performances, and his offer was a ruse to see me. It worked. Jerry appeared at the prearranged time and apologized for the change in plan.

“The theater is closed tonight, and I don’t have friends who leave me tickets. I just wanted to see you.”

Disarming. I played the show’s score on a record player. The song we liked best was “One Hand, One Heart,” a marriage vow based on a traditional Spanish hymn to God. As the last notes faded we looked at each other directly, unsmiling.

I was attracted but not smitten. Not yet. My bliss was walking unencumbered through the winding streets west of the park, so much more inviting than the rigid rectangles in the uptown neighborhood of my childhood. I was intent on a career as a news reporter, hard for a woman to manage in the 1950s. Then, too, a very early relationship with an older man, a C.I.A. operative, in Washington, D.C., had soured me on romance. When he pressed me to sublimate my ambition to his furtive career, I left that spy. The cage unlocked, the door opened, and I saw the world anew.

Alone at last, I was bound for an enlightened single life. If romance had to be followed by marriage—a common precept in those years—I’d have none of it. Still, I was drawn to this new acquaintance from the fountain. I was taken by his eyes, which had the intense gaze of an El Greco saint, and his voice, which was low-pitched and smooth with a ragged edge, the pauses between phrases indicating that he was examining a subject from all sides.

As we talked that night, my interest grew.

“Did you enjoy the folk singing yesterday?” Jerry asked.

“Yes.”

“I treasured it.”

Not knowing how to respond, I picked up the guitar, tuned it, and played an old French song, “À la claire fontaine.” In it, a woman bathing in a fountain by moonlight remembers her lost love and regrets deeds undone. As I sang I thought, Why bathe in a fountain? As with other ballads, the details are exact—three ravens, four horses—but the central situation is a mystery. I slowed down on the refrain:

Il ya longtemps que je t’aime

jamais je ne t’oublierais.

Jerry spoke, swaying to the music: “That’s how I feel.”

“About a lost love??”

“No, about the fountain.”

I doubted Jerry’s enthusiasm, but only at first. I saw him listen to Carol Lawrence and Larry Kert singing on the record we played of West Side Story. I heard him speak of Mozart, whose symphonies he had first heard live in Salzburg in 1954. At the time, he was an Army captain medical doctor with a field artillery battalion stationed in Germany. He had gone with a fellow officer who did not love the music as he did. When I told him I’d just recovered from Asian flu, he said that he was a physician doing research in influenza virus. Noting his modest expertise, I assumed he was good at his profession.

His presence was sparkling, and yet we hardly knew each other. He was open to the arts, especially, I thought, for a physician, but his receptiveness could be simply the momentary appeal of a woman playing the guitar, withdrawn the next day. What if his mind were closed, his views unacceptable? What if we were hopelessly at odds? I was to express those doubts to him on a subsequent meeting when he would reply “Inconceivable” and go on stroking my shoulder. From early on, he had a way of thinking me better than I was, less difficult, less mercurial. I wanted to become the woman he had in mind.

On that first night, we ordered a moussaka delivery from a nearby restaurant and placed the plastic boxes on a table made from a door I’d sanded down and varnished. Unfortunately, the brass legs, badly attached, buckled under. With apologies, I brought a tray to my huge bed, and we settled there.

Yes, we spent that night in the apartment building we were to live in, that he was to die in.

The recognition that we were in love came early. After a five-dollar dinner for two—Jerry’s treat—at Rocco’s on Sullivan Street, we walked home through the park, where white-to-purple hydrangeas glowed even in the dark. We reached my apartment singing “I Could Write a Book,” off-key but in tune with each other. In the park an elm screened a full moon, close to the earth and with a blue-gold halo in humid air. I looked up at the elm, and at him, which was a pleasure: I was unusually tall, standing shoeless at six feet, and he topped that at six feet two. He proposed marriage a week after we met. I held back for two years. I wanted first to find work on a New York paper, and I knew that to most city editors, married women were anathema.

In the meantime, we went to the Metropolitan Opera and heard La Bohème from the fourth tier. It felt odd initially to see Jerry weep for Colline, who sings a bass farewell to the overcoat he has to sell. Finally, though, I was moved. At my place, we put on a long-playing record and danced soft-shoe incongruously to Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. Walking down the street for dinner, we stood before the house where Henry James set his novel Washington Square, bought a paperback, went back, and read scenes aloud to one another. Jerry picked out the phrase “luminous vagueness” in the description of Dr. Sloper, and, seeing me smile, repeated it.

“Is this the house where Henry James’s grandmother lived?” he asked.

“Yes, I think so.”

“It’s supposed to have marble steps and to have very quiet neighbors. It’s not the same,” he said, looking at the book.

“Things change,” I offered.

“We never will.”

“We ought to celebrate our love with presents,” Jerry said that first year. On Eighth Street we bought a long-playing record album for me and for him a pipe whose white bowl resembled a soap castle. We ate paella in a restaurant on MacDougal Street and wrote down the ingredients so we could cook it at home.

Shortly after we met, Jerry bought a guitar at Izzy’s Center, and we played songs of Huddie Ledbetter (“Lead Belly”), which we picked up from a book edited by Alan Lomax. In Jerry’s top-down Austin-Healey, our long legs entangled somewhere under the hood, we drove to the Newport Folk Festival. There, on the Rhode Island seashore, we slept in a tent on the beach, walked barefoot in the oncoming tide, and, sitting on the grass at Fort Adams State Park, heard a slender woman sing “Virgin Mary Had a Little Baby,” a woman who later sang to the world as Joan Baez. “I went to college nearby, but it was never like this. I missed the tones,” he said. Music accompanied our early encounters, and it never faded.

My street lay between two muddy rivers, rust-red at sunset. We liked to walk from the East River, really an inlet, to the Hudson, where we’d look out at New Jersey. Once the Hudson’s wharves held commercial steamers; now one was a depot for errant cars and another a dry dock for an aircraft carrier. Nearest my apartment was the Gansevoort pier, a bare landing that was to become a park for writers and for families with baby strollers. Shortly after sunrise, the waters were murky green, but in places they glistened as though reborn. Ailanthus trees shimmered with gleaming questions. On the way to the river, we’d glanced upward to see the lofty, tawny-red towers of downtown buildings that seemed to be following us. I remarked on the illusion, while Jerry was at pains to discover just why we saw them that way. Avenues were ghosted with fog that lifted as we spoke. This was our river, our neighborhood, our city.

What intrigued me about Jerry was his relentlessly inquisitive mind. I had never known anyone with his irreverence for received knowledge. Jerry challenged easy truths, as I discovered early on. He probed established formulas. Take the morning after a lightning storm, when we ventured outside. Suddenly he breathed deep and tasted the air. “Can you smell the ozone?” he asked.

“I know it’s there.”

“Yes, but can you smell it? It’s supposed to follow lightning, but how can we be sure?”

Or the night we’d come home from a concert at Carnegie Hall to my place. It was late, the traffic was raucous, and we were glad to relax in one big room containing the immense bed and the still-unsteady table that held my typewriter and our meals. While I tinkered with a stovetop espresso maker he had bought for us on Bleecker Street, I noticed Jerry grow distant, forcing his attempts at conversation. He courted me as usual, and we made love with no lessening of ardor. But later that night I woke to see a coin spinning to catch the light from the table lamp. Jerry sat at the homemade table in his pajamas, tossing a penny high in the air. Was he trying to decide something? I wondered. No, his coin toss was to question one of the laws of probability. Four hours, four hundred heads, only forty tails, he said next morning. Not even the final toss—at 6 a.m.—could slake his hunger.

He carried an air of mystery. He was alive with opposites: easy in manner yet stern about principles; a languid walker yet quick in an emergency; casual and yet traditional. In the process of questioning things, from the wind’s direction when he’d run with a kite to the premises of natural laws, he surprised me constantly. Following each of his changes was, for me, like entering a wrought-iron door opening to another door opening to a dark stairway, as in the narrow houses on our side streets. I knew his background, his predilections for Dickens and Mahler, his long arm that reached for a glass of gift Yquem, his slim torso in the cotton T-shirts I bought for him. And yet I didn’t know him at all.

In a generation that eschewed living together before marriage, Jerry and I usually slept in my apartment on the Square. On Sundays, we were careful to avoid my father, who would silently leave bagels and Danish outside my door. There was a duality in his understanding, not uncommon in the fifties. He assumed we made love while simultaneously expecting that his unmarried daughter was chaste. He never spoke of it.

On one of his visits I opened the door, unthinking, and Jerry rapidly blurted, “I came over to drive her to the Grand Army Plaza Library in Brooklyn, open on Sundays.” My father glimpsed the unmarried lovers, left the packages, and disappeared. Jerry confessed, “I know he didn’t believe me. But he liked that I offered him a proper excuse for being there.”

Jerry kept a sunny, white-walled apartment he rented before we met, a walkup in the East Sixties, close to his lab at Cornell Medical College. Even at the height of our joys, I secretly wished for free hours alone. The adventure moved too quickly. I needed time to think and work. One weekend I asked to write undistracted in my apartment, and Jerry agreed to ski in the Berkshires. The next afternoon he phoned, his voice a fading stammer. He had tumbled and broken a shoulder. With abnormal control, he drove himself to New York Hospital for an X-ray. Then, staggering up the six flights to his apartment, he felt his cheeks burn with a high fever. He’d come down with Asian influenza, the prevalent strain he studied in his laboratory.

I rushed up the landings with deli soup, bottled water, and orange juice. His face was grayish, expressionless. Sitting up to drink, he wore a white sheet like a shawl, emphasizing his helpless demeanor. He drank, took his temperature frequently, and made this request: “Either marry me or else phone every hour to check for delirium.” I stayed over, welcoming the chance to make up for the many times he’d tended my family, including three sick uncles, until my mother took to calling him “a great little doctor.” Late the following afternoon, he announced: “Tobin Rote is playing for Detroit against Cleveland.” He was well.

His illness aroused a conflict. Would I be tending this man forever, at the expense of my freedom? Thinking that way, I left and fled down the six flights without looking back. On the bus home, I faltered. I loved him. Helping him get well came with a rush of gratification. Out the window, I saw snow starting to come down, and hail tipped with light.

One month after we met, Jerry’s parents visited “his girl” in her one-room studio apartment. In the last hours of a heavy snowstorm, they drove from Brooklyn, parked blocks away, and trudged in slush. Jerry slung their wet coats over the bathroom shower rod and gave them time to settle in. His mother, Shirley, a robust woman who shone in old family photos, handed me an immense box.

“Latkes. I made them this morning. Jerry said you’d like the way I made them.”

“Oh, lovely. They will go well with the lunch I prepared.” Actually, they didn’t, and Jerry had readied the kosher meal, but I thought the lies might boost her confidence in me.

“Jerry passed his State Boards,” I said, searching for conversation. “That means he’s a board-certified internist.”

“Yes, but you should meet my older son. Edward. He passed his Boards right away. They tell me they’ve gotten easier.”

Jerry shrank in his seat. He, too, adored Edward, his mother’s first and favorite doctor.

“Edward. He’s handsome, like Tyrone Power. Here’s his picture.”

Jerry quickly asked about the drive. His father said, “Fine. I’ve got snow shoes,” referring to tires. Car talk, a welcome relief.

“Edward’s a real doctor, with patients,” Shirley insisted.

The silence sat heavily. She peered around the room and cast a kind but critical gaze on the homemade bed and table. “So you don’t live at home either.” She stopped, meeting Jerry’s frown and noticing his arm on my shoulder. “I mean this is pretty. But now Jerry, he has a nicer home with us than where he goes uptown.”

Jerry’s father’s eyes twinkled as he supported her. “You know what Bernard said—you know, Bernard: ‘It’s a shame that youth is wasted on children.’”

“Meyer!” Shirley rejoined.

Jerry and I exchanged desperate glances. Shirley gestured for a hand to rescue her from the sling chair, and Jerry hoisted her up. She crossed the room to read the dozen Christmas cards I had tucked into the slats of a wood blind. In the hasty preparations for their visit, we had forgotten them. Miraculously, she turned up a card that read, “Happy Chanukah, Grandma.” She turned to me with a loving smile and exclaimed, “Oh, you have a grandma!” Yes, I thought, inwardly thanking my grandma for her ethnicity. Jerry and I breathed freely. He played Brahms on the turntable. Shirley walked over and kissed me. She placed her hand on my head, as in a blessing. Then she took my hand and danced with me. We laughed. Soon after that our parents would meet and charm each other while undoubtedly expressing their common wonder as to why, given suitable homes, each of us preferred to live in close quarters.

They left. While Jerry finished the wash-up, I trekked outside to take in the cold air. The snow had tapered off, but some fluff still clung to the sleeves of coats. I studied a scraggly new pin oak in its fenced-off square of earth on University Place. Despite its enclosure, it would bloom wildly in spring. The visit had pleased me, and yet I feared the snare of family life. My days were unpredictable, theirs were expected. But could I still call myself alone? My love was losing me the resolve to go my own way.