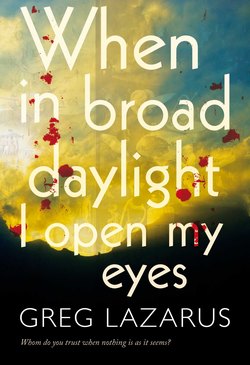

Читать книгу When in Broad Daylight I Open My Eyes - Greg Lazarus - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTwo

Taxis are zipping along Claremont Main Road, veering from side to side, treating the dividing line as a meaningless spill of paint. The air is filled with hooting and emission fumes. Pedestrians bob between the Saturday morning traffic. An old woman serenely follows her own Zen path straight across the road, ignoring the cars weaving around her; a bus bears down on a trio of sauntering young men, who respond with comic running gestures, swinging their arms without speeding up.

Kristof’s small white car passes down the road. He is humming a musical piece, Short Ride in a Fast Machine, imitating highlights from the various instruments. Nearing the finale, he takes a neat left turn into the underground parking lot of a shopping mall.

He runs up two flights of stairs and emerges next to a shop that sells occult books and computer games. Then he turns left and strides past a bowling alley fronted by twitching fluorescent lights and a brace of loitering, scowling teenage boys. Near the alley is a café, Divine Muffin, and next to that is a post office.

As he approaches its glass doors, Kristof sees the Saturday morning queue, a conga line snaking back and forth until it reaches the counter, where five employees are attending to customers. He joins the back of the queue. The line is unusual today: it is visibly moving. In fact, the employees of the post office are handling customers at great speed. Behind the counter they bend to write, stamp blue messages onto black-edged forms, smile as they hand over packages. People walk away from the counter slightly dazed, as if they have just received an unexpected kiss.

In front of Kristof is a young woman whose strong back is covered by a cotton shirt, her dark skin visible as a shadow through the white material. She is wearing blue jeans, and as he stands behind her Kristof begins to whistle. It is an old hymn, yearning, intensely spiritual. His performance, while not showy, is uninhibited; he whistles as he would in his own bedroom. The woman turns and smiles.

“Wow,” she says.

He nods and continues whistling.

“That’s quite something.”

He stops and looks at her.

“Are you a musician?” she asks.

“I wish I were. I love music. And you – are you a musician?”

“I wish! But I’m a huge music fan too.”

The two music lovers smile. They are moving steadily forward, thanks to the hyperactive tempo of the post office employees.

“What’s going on with them?” asks the woman.

“Maybe they’re high on life,” says Kristof. She snorts.

Half a minute passes. “Can I ask you something?”

She turns to Kristof. “What?”

“It’s personal. You might not want to answer.”

“If I don’t want to, I won’t.”

“Do you come here often?”

She laughs. “As much as I need to.”

“Me too.” There is a pause. “I’m Kristof. Would it be rude to ask your name?”

“Umm,” – she bites her lower lip. “Nomsa.”

“I’m glad to meet you. Look at that, we’re at the front already.”

Nomsa goes left, Kristof right. The woman at the counter deftly takes his ID book, stamps a form, has him sign it, and passes him a package. Standing behind her is a grim man, heavily built, arms folded: a post office inspector.

As Kristof walks away from the counter, he neatly slits open the cardboard package with his car key and shakes out the hardcover book inside. It is called Under the Skin of the Earth, and is a collection of photos taken with powerful flashes in trenches at the bottom of the world’s oceans. Waiting for Nomsa while standing at the back of the post office, he flips through the book. There they are, all those miraculous beauties and horrors, captured by scientists deep in their exploration vessels, alone in the profound darkness. A metaphysical lesson reveals itself: reality outstrips the imagination. One sometimes encounters works of philosophy in which the author dismisses a possibility – some social arrangement, or state of mind – on the grounds that he cannot imagine it. But why be bound by his pitiful capacity to imagine the contents of the world? No philosopher could have conjured up the otherworldly physiology of these creatures, yet they exist in abundance.

As Nomsa arrives, Kristof slips his book back into its packaging. “Did you get what you wanted?” he asks.

She smiles and holds up a broad letter.

“I was thinking it would be nice to have coffee,” Kristof says. “Maybe at Divine Muffin. What do you think?”

“I shouldn’t. I have a lot to do.” She flashes him a smile of consolation, and turns to go. Her white shirt, her jeans.

“Are you sure?”

She turns back and nods. Sorry.

“Would you give me a minute? Then you can go. That’s all – just a minute.” She is silent, waiting, as he looks at her with his sharp green eyes. “I guess I’m older than you – by nine, ten years? – but I’m not experienced at this. Now and then I’ve met someone by chance, and thought, well, this could mean something. I’ve never done anything about it, though.”

Her eyes are made up, curves of black, and her hair is braided. She looks like a woman of ancient Egypt.

“I don’t want that to happen again. Just a cup of coffee.”

Nomsa appears to be working something out. A variety of expressions pass across her face; she is performing a kind of moral calculus. Then she reaches an appearance of anxious pleasure. “Fine.”

She is a tall woman, nearly his height. She walks with a strong stride, two silver bangles on her left wrist tinkling. His glide is smooth and quiet.

Divine Muffin is almost empty. On Saturday the students lie in late, and it’s too early in the morning for shoppers to be taking a break from their chores. “Here?” Kristof asks, pointing to a small round table. On the floor he sees a squat portable bar heater, its three strands glowing red, peeping up like an obliging dog. Capetonians are never prepared for winter; their response to the long annual cold season is improvised and patchy.

The waiter comes over to give them a pair of laminated menus, slightly sticky. He is a middle-aged man with a grey ponytail and muscular arms. Even on this cold day he is wearing a short-sleeved shirt. Along his forearm is a tattoo that says “Baby, don’t cry.” Kristof watches the message undulate slightly as the man wipes the table. Punctuation is arresting in a tattoo: skin mutilations usually neglect this aspect of language.

“You know what I like about this place?” Kristof says. “They don’t flood you with choices – only a few flavours, but they’re all good.”

“What do you recommend?”

“That’s a big question. It depends what kind of person you are.”

She arches an eyebrow.

“I’ve learnt some things about you already. For instance, you’re ambitious.”

“Oh, really.”

“And also sensitive.”

“How do you know this?”

“People are what they seem to be. You just need to watch. For example, the way you move – I can see you’re on your way. Also, you’re open to the world.”

Nomsa laughs. “You’re making it up.”

“Tell me I’m wrong.”

She ruminates. “Well, I have a career in finance.”

“There you go.”

“And other interests, social concerns.”

“Exactly: a woman of substance.”

“One day – when I’ve made enough money for it – I want to produce documentaries. Real South African documentaries, you know.”

“Oh?”

“To show South Africans to each other. Deep down, beneath our differences, we’re all the same.”

“Unity amidst variety,” says Kristof, nodding. “Do you know Francis Hutcheson’s work? Hutcheson thinks that unity amidst variety is beauty. That’s just what beauty is.”

“Wow,” says Nomsa. “I mean, that’s exactly – that’s what I want to do.”

“Are you from Cape Town?”

“Joburg.”

“Is your family still there?”

“My dad is.” She rolls her eyes.

“Looks like it’s not bad having some distance from him.”

“Oh, he’s not so terrible. I mean, he kind of is.” They both laugh.

Kristof says, “Now I know what kind of muffin you should have. Coffee caramel. Coffee because you’re strong, capable, alert. And caramel because you’re also kind of a sweetie.”

“Oh my God. You’re such a flatterer.”

“It’s not flattery if it’s true.”

The waiter comes over to take the order: two coffee caramel muffins.

Half an hour later, Nomsa has told Kristof about her job, recently begun, as a junior analyst at a stockbroking firm; the pressure she feels from her father, a tycoon in Johannesburg, for his only child to succeed spectacularly in business and to start a family and raise children, especially now that she is already twenty-seven; and the feeling on some days that she is on top of the world and on others that she is a failure. He nods, grimaces, laughs and shakes his head at the right places.

“You’re a good listener, you know?” she says. Then she adds, “Look, I should have said something earlier. I have a boyfriend.”

“I’m sorry,” Kristof says, grinning, comically slapping his head with his hand. “I should have known. Lucky guy. I’m not going to try anything. I respect your choice.”

“Thank you.”

“Of course, you didn’t know me when you met him.”

Nomsa swats at Kristof with a serviette.

“Just kidding. Anyway, at least I can be your once-off muffin friend.”

The waiter comes for their plates. “Can I interest you in anything else?”

“No thanks,” says Kristof. “I’m happy with what I’ve got here.”

“You’re bad, you know that,” says Nomsa, briefly placing her fingers on Kristof’s forearm.

He allows himself to be touched, but does not offer any physical movement in return. Along with his muffin, he has drunk two strong black coffees. His eyes are sharper than before, his gaze more intense.

“Since we’re only here for coffee, once and never again,” says Kristof, “there’s a kind of freedom in that. I can speak my mind.”

Nomsa waits, her hands now clasped around her cappuccino for warmth.

“Life is short and tough, and there aren’t many moments of grace. But here we are, and there’s that rare electric spark when two souls touch. Even if we don’t see each other again, I’m grateful for that.”

Divine Muffin is getting busier. The tattooed waiter and his colleagues are taking orders, juggling plates on their forearms. The air smells of bitter coffee and baked goods.

“Okay,” says Kristof quietly. “Well, that’s off my chest. It was lovely to meet you, to have coffee with you. And so, goodbye.”

When he gets up to pay the bill at the counter, he puts his hand down on hers for a moment. Her hand is warm, the same temperature, as if they are two parts of the same creature.

Kristof turns off Main Road and drives for a few minutes until he is on the street containing Maria’s house. Two days ago he took this road to the departmental counselling session with her.

He does not see Maria on the street. She is probably in her house; her car is in the driveway. But he drives more around the area – wide roads with broad tar pavements, patches of trees and grass. The streets are calm compared to Main Road: there are few drivers and no hooting. Kristof moves slowly, cruising. The white light of this winter morning sharpens the scene, delineating every tree, rendering the green wire fencing of Paradise Primary School dramatic. In a cul-de-sac, protected from cars by a bollard, three kids are playing piggy-in-the-middle with a tennis ball. He gives them a wave as he passes them. Polite children: one boy waves back, smiles, before throwing the ball high over a girl’s head. Then Kristof sees Maria. He often experiences coincidences of this kind; sometimes he regards himself as a locus of unlikely events. She is wearing a pair of black jeans and a green shirt this morning, an arresting combination with her short blonde hair. Maria is walking up the street, weighed down with shopping bags. Her pregnancy is a subtle curve. It seems that the other philosophers did not notice it at the session – at least, no one mentioned it afterwards – but to Kristof it is quite obvious.

“Hi,” he says, opening his car window and leaning his head out, smiling. “Would you like a lift?”

“Oh, hello,” she replies after an uncertain moment, her hand above her eyes to shield them from the morning light. “Sorry, I didn’t see you at first. That’s very kind of you –”

“Not at all.”

“But I’m happy to walk, thanks.”

“I think that’s great,” says Kristof. “That’s the right decision.”

She laughs, lowering her shopping bags to relieve her fingers.

“That’s the way to exercise – doing real chores. The hunter-gatherer way. Carrying shopping bags is the closest we get to our primal way of life. Except that we don’t hunt down our shopping.” After a pause, he says: “Well, I won’t detain you any longer. I hope you have a lovely weekend.”

“Thank you. You too.”

“It’s a day that makes you glad to be alive, isn’t it? I find that life – just bare life – is quite underrated. Breathing, for example, and seeing the sky. Enormously satisfying, in certain moods. Almost unbearable. But maybe that’s only my morning coffee speaking.”

“Well, that’s a good recommendation for coffee. Maybe it would save people from coming to psychologists!”

“Oh, I don’t think so. Psychology is about as essential as a profession can get. People underestimate the power of words.”

There is a pleasant silence between them. His arm is hooked comfortably out of the window. Her face is a little moist from carrying the bags, even though it is a cool day. It appears that Maria has pushed herself.

“Goodbye, then,” says Kristof. And off he drives. His car, he notices through the rear-view mirror, is watched by Maria as it speeds up the road.