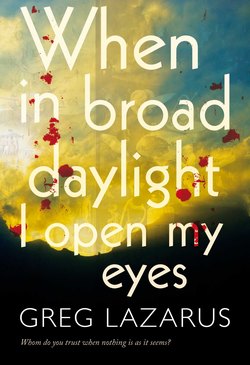

Читать книгу When in Broad Daylight I Open My Eyes - Greg Lazarus - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFive

The slam of a hard object against glass: Maria jolts awake. In her mother’s double bed she lies on her back, paralysed, interlocking hands draped over her belly to form a barrier. What was that? There is only the distant drone of a few cars on some highway. She slides her foot down the cold sheet to break the paralysis, making it possible to move her arms and shift onto her side so that she faces the bedside clock: 2:36 am. Maria stays like that until her breathing settles and her heart slows to a regular rhythm before she flops onto her back again. Through the window she can see the stars, pointy and bright, in the night sky. Claudia, opinionated about almost everything, believed curtains to be unnecessary. “I must look at the stars,” she would say. “So many of my night hours are spent awake, the stars my only companions.”

The house emits its usual sounds, all easily identifiable: the northwesterly wind lashes the awning outside the window, water drips from yesterday’s first winter storm, and a rat, possibly more than one, scurries across the beams in the roof. She can hear the high-pitched squawks of the rodent’s offspring. Is that what woke her? Yet the noise, as she remembers it, was sharper, as if someone were trying to gain entry – not the shrill bleat of hungry young.

Even while she was sleeping, Maria felt disturbed. She is haunted by strange and vivid dreams. They began a week after her mother’s death. The police report hadn’t come out yet, and all she knew was that her mother had fallen to her death from a precipice in Newlands Forest on a Sunday morning. A serious incident, the police said in her meeting with them, takes time to investigate. Seeing her agitation, the sergeant and his assistant had promised to pray for her. She told them rather to concentrate their efforts on police work, which produced a resentful silence.

Maria’s first dream came as a block of colour, fiery orange, filling her vision. Parting the orange curtain, Claudia glided through, her long black hair framing her face. There were more dreams: sometimes her mother stood at the top of a stone tower, similar to the one on the tarot cards she used. Maria had the sensation, comparable to that which she felt with her clients, that Claudia was about to tell her something important. If asked, Maria would have said that her mother was trying to say goodbye. Despite their difficult relationship, and her sense that she was never truly wanted, Maria believes Claudia wanted to offer her farewell before killing herself. Sometimes she thinks this is only what she wishes to believe, but she feels it strongly.

Of course she expects such dreams, this re-encountering of the dead during sleep, when the unconscious has free rein. In her night life she recreates a wish: a living Claudia. But – and here she can barely give voice to her thoughts, because she has always seen herself as not only intuitive but also rational – there is something odd about these night images. Always it appears to her as though she is awake, and even upon waking she has the sensation that she was not asleep, so vivid are the dreams.

Maria forces herself up from the warmth of the bed for some water. These days she gets so thirsty, it feels more like she’s drinking than eating for two. She makes her way to the bathroom used by her patients, where the light is dimmer, to avoid a further push into wakefulness. The room is spare – only a toilet, a tiny porcelain basin (if the tap is turned a touch too hard, the water sprays the tiled floor) and a medicine cabinet.

She bends to drink from the tap, letting the cool water flow over her lips. A sleeping pill is what she wants. Since her mother’s suicidal plunge, she has not only endured unsettling dreams, but also insomnia. For this she resents Claudia. Maria has tried everything to cure herself, from valerian root to long and tedious runs in the late afternoons – nothing worked, so many wasted hours. Eventually she grew tired of the thoughts that circle in the early hours of the morning, and found a doctor with an easy hand, a poor sleeper himself. Now, with the pregnancy, she dares not risk the blank pleasure of a sleeping pill – though, on a few desperate occasions, she has sliced a pill into quarters, knocked it back with a capful of wine – but the nights for the most part are taunting and never-ending. She opens the medicine cabinet, knowing precisely what it contains: Panado (many patients come to therapy with a headache, or develop one during the session), a spare box of tissues and a brown bottle of PaxMax, a herbal remedy for anxiety.

At first she fails to register – her thoughts are confused, a stew of recently departed sleep hormones overlaid with adrenaline – that the missing blue gecko is at the centre of the bottom shelf. How odd. But there it is, sitting slyly, body curved in mid-slither, reptilian head facing her. Maria picks up the creature so that it lies flat and cold in her palm. She flips it onto its back, noticing the contrast between the blue glossy surface and the white underbelly with its thumb-shaped indentation. Again she mulls over the idea that one of the philosophers placed it there ten days ago – but which one? She rules out Luke immediately. Too serious, too disturbed by Saskia’s disappearance; such behaviour would never occur to him. Also, if she remembers correctly, he didn’t leave his seat. Perhaps Joan Castle? Joan, however, does not seem to possess the required levity; for her there would be no point in such a silly act. Cyrus Jackson? Too smooth and efficient to waste time with hijinks like this. Kristof, she thinks, the cheekiest of the group, is the prime suspect. A prank like this might appeal to him. Maria leans against the wall, closing her eyes to extract the memory of that session. She remembers, she thinks, Kristof’s meander to the bookcase at the end of the session, his quick tracking of a finger across the spines of her books. At the time she’d felt the gesture to be strangely intimate, the silent touching of her books as though his fingers were learning her contours. And hadn’t he asked to use her bathroom? The possibility tips her into full consciousness. Despite the late hour, and her frustration at not sleeping, she smiles, amused by the trick. Of course she can understand the wish of a patient to get one over on the therapist, to level the power. She walks back to the bedroom with the gecko in her closed hand. The lizard takes on the warmth of her skin as she lies in bed, still holding it. It occurs to her that Kristof simply wants her to think of him. This desire she recognises: most of her patients crave her intimate attention, and – in truth – their need for her is gratifying.

Maria must have drifted off, because when next she opens her eyes the sky is white, and a high-pitched chirping comes in volleys from outside. She turns, the gecko on her pillow more endearing than sly in the light of day. Its presence, seemingly calm and thoughtful, lifts her mood despite yesterday’s awful blow-up with Lionel at Kalk Bay. During the fight, her attention was drawn to a youth of no more than seventeen, an inflamed red eruption of pimples on his jaw line. He was fishing, his body as taut as the line.

“Look,” she said to Lionel, desperate for a distraction. “He’s caught a fish.”

“I don’t give a fuck. Listen to what I’m saying: I want you to move back in with me. You’ve been in Claudia’s house now for months. A dead woman’s house –”

“My mother’s house.”

“I know,” he touched her shoulder. “That’s not what I meant. It’s not about her. I want you – need you – back with me.”

“What’s changed, Lionel?” She couldn’t even believe she was having this conversation with this man.

“You’re carrying our child, for a start.”

“That’s going to make you faithful? Don’t make me laugh.”

He placed his hands on her shoulders, making an effort to be gentle, though his fingers were digging into her skin. Lionel faced her out to sea, as if he were adjusting a mannequin in a shop. “Having a child together does change things. How can it not?”

She felt her old surge of anger towards him. “So that’s what’ll make me your number one, that I’m carrying your genes? Tell me, are your genes so great? And how long before I slip down your list again? How long until I’m not your number one,” she held up her hand, index finger outstretched, “or even your two,” second finger snapping up, “or three? How long until I’m your number ten, or fifty? It all depends, Lionel, doesn’t it, on how many women you can lure into bed. And for some reason there are lots of us out there – myself, idiotically, one of them.”

“That’s totally unfair. I’ve told you I’ve changed, I’m a completely different –”

She rolled her eyes, snorted in derision. That’s when he pushed her, or at least she thought he did. Of course he said he didn’t: “Are you out of your mind, do you think I would deliberately hurt you? What kind of a madman do you take me for?” He said he tripped – over what? – and fell forward, bumping hard against her shoulder so that she stumbled but righted herself before falling. It must have looked odd, she thought afterwards: out of nowhere, Lionel falling on top of her as she staggered backwards under his weight. Muscle weighs more than fat, she’d thought irrationally at the time, and Lionel, though not tall, was solidly packed.

“Even if it wasn’t conscious, you wanted to hurt me,” she told him, and he shot back that she spoke a lot of crap – and so their fight continued, but at least they stopped talking about her moving back with him. Finally there were apologies and protestations of love from him. At one point he put his arm around her and they stood on the pier, her body stiff next to his.

“I can’t live without you. You know that, don’t you?” he said.

“No, I can’t do this again, Lionel. It’s – just exhausting.”

He was silent for a while. Then he quietly said, “Also, to lose your only parent, and so suddenly. It takes a long time to recover from that.” She’d said nothing. Afterwards, as they walked back to the car, he held her hand. “I’ll be here for you, Maria,” he’d said as he opened her car door. “Please think about what I’ve said. I need you with me. You need me, too, especially after Claudia’s suicide.” He touched her belly with his hand as she sat. Inside his car, she kicked away the papers and old water bottles that formed a thick layer at her feet.

“Sorry,” he said as he closed the door. “I’ll clean it up.”

On and off, this relationship, and each time it drained her. The instability of their bond was caused not only by his many infidelities, but by a secret she had kept from him, something she mostly avoided thinking about. Her pregnancy made her want to cling to Lionel, a strong force despite his unfaithfulness. Yet several times she had broken it off not only because of his affairs, but from disgust at her own deceit.

She glances again towards the gecko, now perched on the bedside table. This time the lizard reminds her not of Kristof but of its actual owner, Claudia, and the task of finally cleaning out her mother’s bedroom. The room is unchanged since her mother’s death in September: desk piled high with astrology books, cupboards stuffed with her mother’s clothes. Every day she has to manoeuvre past objects – the wooden chest at the end of the bed, the recliner chair – to get between the door and the bed. Adding to the chaos, aromatherapy burners lie scattered on the floor. Maria sits on the unmade bed, gathering her strength for the clean-up ahead.

It is not like her to live in such a mess; she deals with it by using the bedroom only for sleep. She wouldn’t have moved into the house at all if the break-up with Lionel hadn’t occurred at the same time as Claudia’s death. Her plan today is to pack the stuff, all of it, into boxes and give it to a charity. Let them dispose of the junk. At least the room will then become more habitable.

Though she hasn’t cleaned out the place, she has searched it a number of times, digging her hands into drawers, rummaging through the contents of the bedside cabinet. What is she looking for? A communication, some kind of explanation from Claudia. A farewell note, written only for her. She has read the police report, produced some months after the event, so many times that she knows it by heart: Survey of scene showed no evidence of foul play . . . woman in her mid-fifties . . . judged a suicide.

The scent of lemons in the bedroom is strong, from the residue of the oils in the aromatherapy burners. Unbidden, the memory rises of the first time she took her mother walking in the forest. Exercise, Maria had told Claudia, was almost as effective in lifting the mood as antidepressants. And the fresh air, the scent of pine, would be rejuvenating.

“I’m not depressed,” Claudia had said. “There’s a difference between a depression and the abyss. The abyss needs to be travelled – it’s a long descent.”

But despite their arguing, she had for the first time followed one of her daughter’s suggestions. After their first trip together, Claudia went alone, preferring the solitude to her daughter’s company. “When I’m by myself,” she said, “I see things that aren’t visible otherwise.”

Before Maria can stop herself, she heads to the kitchen for half a Hunter’s Dry to steady her nerves for the day ahead. The rest she pours down the sink, watching it fizz like acid. I’m past the first trimester, she tells herself, as she begins with a buzz of activity. A small drink is fine. She opens drawers, chucking clothes into black bags. First goes underwear: panties and bras, almost unbearable to touch. Outside, Chicken and Egg, Claudia’s two black Labradors, are lolling in the sun. Chicken is on her back, her legs parted to expose a tender belly to the weak light; Egg lies panting on his side. Her mother rescued them from the SPCA, naming them on their day of arrival. (Maria: “You can’t name a dog Egg!” Claudia: “Oh, Maria, show some spark – Chicken and Egg, a perfect unit, just like the world and the afterworld.”)

She’s doing the clean-up too quickly, grabbing huge handfuls of fabric (she doesn’t bother to pick up a flowing green skirt that falls to the floor), filling bags halfway, knotting the tops with a twist and a pull, lining them up like schoolchildren all in a row in the passage. She flings open a narrow cupboard: shoes, and behind a row of empty shoe boxes, hidden from her initial view, is Claudia’s laptop. Her machine! Maria searched for it previously, but without success. Finally she decided that Claudia must have given it away.

How sceptical her mother had been when she bought the laptop – how would she ever learn to use it? – but when Claudia found out that she could do complex birth charts using software, she became determined to master it. She would sit too close to the screen, now and then giving it sharp slaps as though to force the electronic circuits to release their secrets.

Maria powers up the machine before she can stop and think about what she’s doing. Perhaps here she’ll find the communication she’s seeking, the final note, lovingly crafted. A cursor appears; the computer is demanding a password. Who would have thought Claudia could get it together to protect her documents? And what word would she choose? Maria types Claudia – a good first guess, she thinks – but without success. Then, after a moment’s hesitation, she types her own name. Incorrect. Please enter the password. Perhaps she should try some esoteric astrological term, or the name of one of her mother’s lovers. She hits the machine in frustration, and then, embarrassed by her impetuous gesture, finishes the job of cleaning out the bedroom.

That afternoon, she takes Chicken and Egg for a walk. There is a dead bird outside her bedroom window – she remembers the slam from last night. Even though she scoops up the poor creature in a plastic bag, denying the dogs a chance to pull it apart, the sight of the carcass has enlivened them. Their energy is suddenly boundless for their Sunday outing.