Читать книгу The Amazing Bud Powell - Guthrie P. Ramsey - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

In August 1966, William Powell, Sr., found himself speaking to the press about times past as he prepared to bury his son, the gifted jazz pianist, Bud Powell. He reminisced about giving a four-year-old Bud his first piano lesson after being cajoled by his wife, Pearl, to provide some instruction to keep the child from banging on the piano, something Bud enjoyed doing. “That started it,” he told the New York Amsterdam News. As he recounted memories for the reporter, William expressed pride in his son’s accomplishments, no doubt to fend off his sense of loss and regret. He ticked off a list of his son’s accomplishments, from his diligent study of classical piano as a child to his years as a teenage titan in jazz. Powell, Sr., wanted the world to see Bud as he himself recalled his son in early life: “We used to call him ‘happy’ because he was always laughing and was a healthy youngster.”1

At press time, his son’s remains had been held in New York’s Kings County Morgue for more than forty-eight hours since his passing on July 31. Awaiting legal permission from his next of kin to carry out an autopsy, hospital authorities tried to reach out to his estranged wife, Audrey Hill, then living in California, but their efforts apparently failed, since Bud’s father had to send the morgue a telegram that would allow his body to be released shortly thereafter.

By the time of his death, Powell’s health struggles were well known throughout the international jazz world. Before he had come back to New York in August 1964 (he had lived in Paris since 1959), the press had hailed his impending homecoming with enthusiasm, despite reports of his life-threatening illnesses and hospitalizations in Europe. Powell recuperated and aspired to make a comeback in the United States. When he arrived in New York, “cured of TB and fat as a Bürgermeister,” he was immediately booked at Birdland for an extended engagement, for which he received favorable reviews.2 Powell’s former manager, Oscar Goodstein, no doubt planned the appearance with high hopes that the pianist could return to one of his old gigs in grand form. Could he recapture some of the magic of years past now that he was well and had the added mystique of a Parisian pedigree?

How the engagement went depended on whom you asked and which night they saw him. Greeted by a seventeen-minute standing ovation when he first took the stage, the night of August 25 was filled with promise. But when he didn’t show up for the gig one night in October and went missing for two days, it became clear that returning to New York was perhaps not the best idea for his health. Powell was fired from the gig, and things would get worse. His devoted friend and caretaker Francis Paudras—the man credited with saving Powell’s life, who had accompanied him to New York—returned to Paris without him. Powell would now have to work out his life and career issues without the benefit of his trusted “supervisor.” When he had first landed in New York, Powell declared that he was looking forward to managing his own finances. That time had come.

Money turned out to be just one of his many challenges. If Powell planned to get solvent by jumpstarting a recording career, his discography tells of the bleak results. He recorded only sparingly between September 1964 and January 1966. Beyond the first album, titled The Return of Bud Powell, on the Roulette label, the rest were recordings that lacked the necessary quality to be released to the public. The recordings have, however, inspired lots of debate, detective work, and speculation among Powell discographers as they’ve tried to figure out the who, what, when, and where of these scant, intriguing unissued records. Everyone agrees on one thing: Powell only hinted at the virtuoso prowess he had once flaunted with ease.

These final contributions to his body of work were a far cry from the high hopes he and Paudras had held as they planned their stateside trip: “Bud was going to be back on top, buoyed by the certainty that he has recovered all of his powers, ready to plunge into a new life, freed from the spectres of the past.”3 But as Paudras’s copious, personal, and poetic account of Powell’s last days in his book The Dance of the Infidels details, the misfortunes of the pianist’s past were always close at hand, ready to swallow him whole. Indeed, as Paudras points out, more often than not Powell’s psychological issues positioned him on the weaker side of interactions with the businessmen, police, psychiatrists, attorneys, and even journalists with whom he had to contend throughout his entire adult life. When all was said and done, and as Powell and Paudras would soon learn, the mid-1960s New York jazz scene could not offer him the new life of prosperity, calm, and artistic acclaim he so desired.

Reality hit as soon as he stepped off Air France flight 025. With all of the excitement generated in the press and by Birdland’s publicity machine, Powell’s upcoming residency was eagerly anticipated. However, as Paudras would learn, the American way of jazz business was stark, unglamorous, and undignified. Goodstein had booked them into a rundown, roach-infested single hotel room with a kitchenette for the entire stay. The advance consisted of the following, according to Paudras’s dramatic account: two one-way plane tickets, thirty dollars between them for immediate expenses, nine hundred dollars for back dues he owed the musicians’ union, room and board deducted from Powell’s future earnings, and seven hundred dollars for an attorney to clear up various legal actions before he had expatriated himself. And then there were the narcotics testing, fingerprinting, and police notification that would all verify that he had been cleared to receive a cabaret card, which would in turn allow him to perform in a New York nightclub. That engagement, of course, was the reason for the business trip.4 It had to work.

There was much to cheer them on. Time, Newsweek, Down Beat, and the New Yorker covered Powell’s return to the American stage and praised him with solid, enthusiastic reviews. Musician friends offered a steady stream of admiration and love—Max Roach, Thelonious Monk, Barry Harris, Babs Gonzales, Elmo Hope, Mary Lou Williams, the Baroness Nica de Koenigswarter, and others celebrated his return. Each had supportive contact with Powell between the time he arrived and the time he passed away. But during those two years, his life unraveled—gradually and in dramatic fits and starts—in a manner that was all too reminiscent of his old struggles. His body, now ravaged from the effects of tuberculosis, could not heal. He chain-smoked and craved alcohol. One drink would immediately debilitate his performances and severely rattle his emotional balance. Drugs abounded in this atmosphere. And to make matters worse, sometimes Powell would suddenly disappear, sending everyone into a panicked search around the city.

By this time, Powell appeared to be closer to his French guardian than to his own family. His mother had died and his father, by Paudras’s account, had no room for Powell in his home or psyche. When Bud showed up one night at his father’s Harlem apartment, unannounced and drunk, the elder Powell called Paudras to come and take him back to the hotel and warned Bud to not come back; his presence was too much to handle. Bud’s then teenaged daughter, Celia, and her mother, Frances Barnes, had moved to North Carolina. At Paudras’s invitation, they made the trip to Birdland, reuniting father and daughter for the first time since she was a little girl. They moved back to Brooklyn, and Powell soon began living with them. He began to drink heavily, too, growing weaker and weaker physically.

His last public performances of note took place at Carnegie Hall at a Charlie Parker memorial concert in March 1965 and at Town Hall on May 1 of the same year. Reports from observers of those concerts toggle among shock at his deteriorating physical appearance, memories of his once stunning musicianship, and disappointment in his failure to live up to them. Some called the Town Hall date (which was arranged by Bernard Strollman, Powell’s attorney since his return to the United States) simply disastrous. But all around him remained hopeful that they could get a glimpse of the musician who had rocked the jazz world to its core and helped to shift its aesthetic center.

He was hospitalized on June 28, 1965, and given a moderate chance of survival because of his serious pulmonary complications and other issues, including jaundice and abdominal dropsy. He remained at Cumberland Hospital for five weeks, some of that time spent in critical condition. Powell was not a forgotten man, as evidenced by the many visitors, cards, and letters that came to the hospital. Mary Lou Williams and Max Roach, old friends from the glory days, both visited before he was discharged in August.

Amsterdam News reporter George Todd visited Powell as he convalesced in Brooklyn. Described as “the home of friends,” the apartment in which Powell stayed was on the second floor, and the climb, Todd noted, exhausted Powell to the point of breathlessness. Powell could not, or at least would not, respond to questions. Celia Powell and Frances Barnes cared for Powell in his last days. Even with this support system, however, his physical and mental health continued to spiral downward. His drinking also increased, which meant, of course, that his music languished. Insisting on drawing Powell out and apparently keeping the best face on for the press, Frances told George Todd that she’d been in love with the pianist since she was fifteen and that Powell had planned to spend his time composing new music.5

Concerned friends reported by letter any information that they learned about Powell to his friend Francis in Paris. The news was mostly bad. Making matters worse for Paudras, he was in a battle with Strollman over some recordings of Thelonious Monk’s compositions that Powell had made when he lived in Paris. A letter from Alan Bates announced that Powell once again had been institutionalized by November 1965, this time in Kings County Hospital, where he was making progress and losing some excess weight, although his teeth were rotting from neglect. He was allowed to play in “a half-assed band” in the hospital twice a week.6

By April 1966, he was living in Brooklyn with Frances Barnes and her and Bud’s teenaged daughter, Celia, and he was struggling physically but mentally stabilized. A circle of Paudras’s friends plotted in vain to take Powell back to France, where they believed he would thrive once in his friend’s constant care again. Their hopes were dashed by news reports that he had fallen seriously ill in early July. After another stint in Cumberland, Powell was transferred to the psychiatric hospital in Kings County, where doctors, against his wishes, were planning shock treatments to his brain. Frances intervened, but he couldn’t hang on. Earl “Bud” Powell was given the last rites of the Catholic Church and passed away on the night of July 31, 1966, at the age of forty-one.7

The jazz community, together with Powell’s family, associates, and fans, honored his memory in grand style and with reverence. His body lay in state for three days at Unity Funeral Chapel in Brooklyn, surrounded by impressive floral displays, provided by his family, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Mary Lou Williams, and Alfred Lion, among others. Close to five hundred visitors—an interracial crowd of young and old—paid their last respects at the police-managed event. Following this, a New Orleans–style funeral was held in Harlem. The procession, which was led by the Harlem Cultural Council Jazzmobile and an honor guard, slowly filed up Seventh Avenue toward St. Charles Catholic Church on 141st Street, which he had attended as a child. It was truly a jazz community affair: pianist Barry Harris was among the musicians performing; Nellie Monk, Thelonious Monk’s wife, was on the committee planning the funeral; and Max Roach and Local 802, American Federation of Musicians, were among those recognized for their role in the financial arrangements. Powell was laid to rest in a family plot in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, the town outside of Philadelphia where his mother had lived.

BUD POWELL: THE EXCEPTIONAL ARCHETYPE

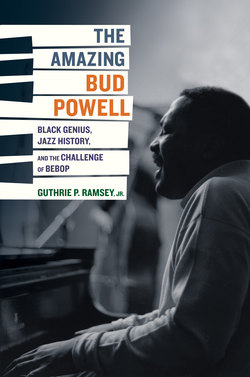

The extent to which the public and the jazz community celebrated Powell’s life is a testament to his contributions to American music. This book discusses some of the reasons that he continues to be one of the most intriguing musicians of his time. The Amazing Bud Powell is not an exhaustive biography. Rather, it puts what we know about Powell’s life and music in dialogue with ideas that made possible, among other things, his reputation as a musical “genius” and bebop’s social identity as a singular art form. Jazz letters have circulated these notions about Powell’s impressive artistic stature, and these sentiments are directly aligned with the music’s ever-evolving social pedigree.

Throughout this book—which is the first extended scholarly study of its kind on Powell—I explore questions concerning the relationships among Powell as a figure in American music, bebop as a sonic discourse, and the writing of jazz history as a political activity that engages many issues beyond musical aesthetics. Within these connections, Powell emerges as a complicated subject, both typical and exceptional among his peers in modern jazz. Powell was an archetypal bebop musician, and his accomplishments, much like those of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, and Thelonious Monk, inspired the expansion of artistic horizons for black artists across varied media at midcentury and beyond.

And yet within this paradigm of African American experimentation, narratives of Powell’s exceptionalism abound, and this book treats, but does not attempt to resolve, these tensions. Like the dissonant intervals that define the art of bebop itself, they are allowed to languish here, resisting my desire to manage—to make stable, consonant, and neat—what is truly a robust, multidimensional, and unruly historical subject. With that in mind, then, Powell’s life, music, and the analyses of them reveal a complex and dynamic picture of one of the twentieth century’s most beautiful and fiercely adventurous musical minds. His artistic commitment not only codified bebop piano, but also beat a path for the language of musical abstraction that would stun the jazz world during his final years.

This book is about more than one musician’s inspiring accomplishments. It is also about the various meanings that can be derived from the bebop movement, in which Powell was an innovator. Powell’s amazing muse—his expansive musicianship, riveting improvisations, and inventive compositions—can be best understood within the broad social, musical, historical, and especially marketing frameworks in which listeners experienced and understood him. Thus, this book considers the relationship between the sonic details of bebop—particularly Powell’s engagement with them—and the “performance rituals, visual appearance, the types of social and ideological connotations associated with them [the musical details], and their relationship to the material conditions of production.”8 This book, then, is also about how bebop and the social networks in which meanings about it were made, and how all of these things suggest that jazz had experienced a generic shift. Jazz, according to many, had become a new “genre,” and it did so partly because of Powell’s important contributions.9

The idea of genre in this study involves many factors, including the pressing business of labeling in popular culture; the tidal wave of “Negro” artistic experimentation and the surging black political efficacy that characterized the 1940s; modern jazz’s evolving critical discourse; the gendered musical language of bebop genius; and the potent atmosphere in which new identities and identifications were being made at this historical moment. During these years and set against these influences, Powell began his rise as a bona fide giant of modern jazz piano—just as black popular music and the social sphere it inhabited were experiencing the tumultuous changes mentioned above. His work is, therefore, ideally suited to an exploration of shifting notions of genre in jazz. Why? Because he was one of the key musicians who supported jazz’s perceived move outside the tight constellation of “vernacular” styles such as blues, gospel, jump and urban blues, rhythm and blues, and, later, rock ’n’ roll. And he is an exceptional example of this shift because even while he helped to codify bebop’s language, he developed an idiosyncratic, forward-looking voice within it.

THE SOCIAL CONTRACT IN BEBOP’S CHALLENGE

Jazz is singular in that its social mobility—its ability to move among “folk,” mass culture, and “high” art discourses—has been the subject of meticulous scrutiny. Through the years, divergent theories about it have surfaced as observers debated whether jazz was the music of an ethnic, subcultural folk, a popular music intended for mass audiences, or a cultural expression of the highest order, one requiring an elitist, specialized training to adequately comprehend its value. As such, we hear in its history the audible traces of this struggle for a cultural and social identity, the commercial interests of the music industry, and the “changing orientations and perspectives among working-class and middle-class African-Americans, especially black youth and young adults.”10 To this latter point, I note that at the time that Powell was building his early reputation, jazz occupied a similar cultural-social position to the one that hip-hop has held for the last thirty or so years.

When bebop drummer Kenny Clarke said he resented the label “bebop,” he joined a chorus of critics who understood the power as well as the limiting effect of musical labels. Yet labeling has been a major preoccupation in the world of arts and letters, particularly in the specific case of music, where the act of categorizing performs many functions. Stylistic distinctions, for example, tell us much more than which musical qualities constitute a piece of music. They shed light on what listeners value in sound organization. Categorizing also inherently comments on the nature of power relationships in society at large—it tells us who’s in charge and running the show. As bebop musicians were keenly aware, if you named it, you could claim it. In the “on the ground” listening experience, labeling establishes the rules of the game, allowing listeners to perceive the relationship between the idiosyncrasies of a single piece of music and the larger category of sound organization to which it belongs. Thus, a good deal of cultural work is achieved by the act of stylistic labeling: it provides a social contract between music and audiences, one that conditions the listeners’ expectations on many levels, particularly in the area of meaning. When one considers, for example, the range of musical tributaries flowing through Powell’s aesthetic sensibilities—as this study does—it becomes obvious how labels can constrain or discipline interpretations of a musician’s work.

African American music in general is a particularly rich site for exploring issues of stylistic labeling. Critics, scholars, and listeners have recognized that the singular historical experience of African Americans is perhaps the most compelling reason that the conventions of black music have inspired such powerful reactions. The ideology of race has, of course, contributed to the dynamic reception of the history of music labeled “African American.” And beyond this aspect of their shared social histories, the genres jazz, gospel, rhythm and blues, soul, blues, and hip-hop contain strong familial relationships based on common characteristics that many, despite contestation, continue to trace to an African cultural legacy, as well as other sonic tributaries originating in Europe and elsewhere. Despite their commonalities, however, these genres have distinguished themselves and are marked with social, historical, geographical, and commercial particularity.

Generic labels such as “jazz” guide listeners toward the “proper” responses as dictated by a social contract established by the label itself. They establish a framework for the communication of meaning, provide a context for interpretation, and serve as a starting point from which to discern changes or innovations. To be sure, positioning a musical practice in this or that category carries important consequences: it connects the music and musicians to commercial institutions, genre-specific interpretations, and traditional audience bases. Thus, when sound organization is assigned a genre designation, the name speaks to both purely musical issues and to larger social orders. Musicians are keenly aware of this fact.

I should back up a bit here and make clear how I’m using the terms genre and style. Important and helpful accounts tracing the etymology of these terms already exist, so I will not recount them here.11 I use genre to refer to the broadest categories of musical and social practices. The term style, for me, designates subsets of such practices. These groupings are always flexible and situational. For example, we use the term black music to indicate a large range of styles closely associated with the social and historical experiences of African Americans. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., among many other writers, links these various styles by identifying a common set of conceptual approaches. When we turn to jazz specifically, the labels Dixieland, swing, bebop, modal, free, fusion, and acid represent substyles that have been subsumed under the “jazz” genre.12

Because musical practices tend to be dynamic, categorical designations are always moving. Consider the relationship of blues and gospel. On the purely stylistic level, they shared many common qualities in the 1920s. But as we see in the music of Thomas A. Dorsey, the “father” of gospel music, for example, socially grounded beliefs about each category of music (blues and gospel) began to codify. Thus, although they continued to share formal conventions, they became separate genres of music, a move that the commercial market perpetuated and helped to solidify. Categories or distinctions such as these performed a good deal of cultural work. They carried the baggage of social hierarchies: some genres fit into the “art” category of culture, while others were viewed as mass or folk culture. To further clarify this point, bebop permanently changed how jazz was viewed in the value system of American musical culture and represented an important rupture that was felt beyond the music world. This book seeks to index some of those changes by considering Powell’s career and music. Indeed, the specifics of his art and the identity he fashioned with it bring into sharp relief some of these shifting perceptions.

THE BEBOP FIGURE IN JAZZ HISTORY

One way to interpret these changes in the music’s social pedigree is by considering jazz historiography, or the history of writings on this topic. As such, my work engages a wide range of literature with the deliberate intention to contextualize Powell’s work. I should mention at the outset that I situate my own work within two broad historiographical streams. During the 1960s, the final years of Powell’s life, two vibrant studies appeared or were underway, and each of their premises is central to this book’s methodological approach. They are Gunther Schuller’s Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development (1968) and LeRoi Jones’s (Amiri Baraka) Blues People: Negro Music in White America (1963).

When it was published, Schuller’s work promised to be a model for future jazz studies: a book-length treatise on jazz that explored its sonic qualities with rigor. In his opening paragraph on its origins, Schuller gives what one has come to expect from his writings: an emphasis on the notion of development: “Jazz . . . was not the product of a handful of stylistic innovators, but a relatively unsophisticated quasi-folk music—more sociological manifestation than music.”13 Schuller moves on to give the most thorough technical discussion in any jazz narrative to that date of the transformation of African and European musical practices into an uniquely African American one. Schuller considers form, timbre, melody, harmony, rhythm, and improvisation with the tools of western music analysis. The remainder of the book maintains this standard, with formalist, technical explanations of a large body of jazz recordings.

Some saw this approach as purging the sonic of its social (or even cultural) meaning. In his essay “Jazz and the White Critic” (1963), Amiri Baraka argues that “Negro music is essentially the expression of an attitude, or a collection of attitudes, about the world, and only secondarily an attitude about the way music is made.” Furthermore, Baraka believes that white critics’ approach to jazz criticism stripped “the music too ingenuously of its social and cultural intent. It seeks to define jazz as an art (or folk art) that has come out of no intelligent body of socio-cultural philosophy.” Baraka draws a hard line with what he sees as the search for organic unity and structural coherence: “In jazz criticism no reliance on European tradition or theory will help at all.”14 At the same time, however, Baraka insists on the uniqueness of the American experience and argues for “standards of judgment and aesthetic excellence that depend on our native knowledge and understanding of the underlying philosophies and local cultural references that produced blues and jazz in order to produce valid critical writing or commentary about it.”15

With Blues People, Jones attempts to develop what he sees as a more appropriate theory for black music. Its reach has been broad: one writer hails it as “the founding document of contemporary cultural studies in America” because of the way Baraka combines aesthetic judgments with poignant cultural and political critique.16 Not everyone agreed with this “social” interpretation of black music. In his famous review of Blues People, the African American novelist Ralph Ellison draws a line between art interpretation and sociology, arguing that “the blues are not primarily concerned with civil rights or obvious political protest; they are an art form and thus a transcendence of those conditions created within the Negro community by the denial of social justice.”17

My work here flatly rejects the notion that music itself can transcend, in the sense suggested here by Ellison, the conditions of its historical and social milieu. Yet historical actors have certainly used music to assert their own senses of beauty as well as to make sense of, confront, negotiate, and/or change their social, political, and economic conditions. Music’s ability to do this kind of cultural work is, in fact, one of the reasons we find it such a powerful medium. The Amazing Bud Powell attempts to uncover the cultural work of Powell’s music partly by dealing with issues, methods, and questions appearing in Early Jazz and Blues People. How, I ask, do we make sense of Bud Powell’s music as that of someone whose talents could never lift him above the challenges he faced as a uniquely gifted but disabled black American man at a time of tumultuous transitions in the material conditions of African Americans across the board? What were his musical contributions, the structure of his sound language, the broader stylistic worlds he engaged, the conditions of the music’s reception, and the critical discourses that surrounded and tried to make sense of it? In what social orders did bebop emerge, and how did musicians such as Powell navigate them?

• • •

My first chapter discusses the idea of bebop’s pedigree as a serious art: how that concept emerged and which musical, social, literary, and pedagogical discourses support the claim. From today’s vantage point, the “art of bebop” notion condenses a collection of disparate yet interdependent factors: formal musical analyses, commercial interests, subcultural visual styles, western ideas about musical “complexity,” aesthetic multiplicity and sonic assemblage, traditions of avant-garde black youth culture, violent state-sponsored suppression, the cultural politics of geography, a jousting written criticism, a discerning and thoughtful audience base, and a politically focused body of interdisciplinary scholarship. Powell’s points of intersection with these variables form an important thread in this book.

In chapter 2, Powell’s artistic agency, together with his life’s challenges, is situated in the context of modern jazz’s growth in the music industry and in the broader world of black artistic experimentation in the 1940s and 1950s. At the same time that Powell was building a name in the jazz world, poets such as Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks were refining, and indeed remaking, the black artistic landscape through their bold experiments with the written word. Painters such as Norman Lewis were also troubling artistic waters with the visual language of abstraction as practiced by the always politicized creative imagination of the black man. The chapter places Powell’s life as a musician squarely within the context of the various identifications he made during bebop’s early development. By identifications, I mean the specifically musical and social associations he made among the choices that were available to him. In my view, it is impossible to fully appreciate Powell without considering, in some relevant way, the work and lives of his contemporaries. He and the other modern jazz musicians all “made” bebop within the music industry’s business practices and venues. As we learn, Powell’s genius was geographically, historically, and culturally specific. It did not, and in fact could not, transcend its milieu—indeed, his genius was a product of its time, place, and artistic position with other musicians in bebop’s orbit.

Chapter 3 focuses on three broad social orders: art discourse, the idea of “blackness” in historical jazz criticism, and American psychiatric practice. I treat each of these as important structural factors with undeniably direct and indirect bearing on our contemporary understanding of Powell and his accomplishments. The role of race “thought and practice” in jazz’s literary aesthetic discussions and in the pianist’s experiences with psychiatric institutions throughout his adult life animates and connects these seemingly incongruent discursive spheres of influence. As we shall see, the compelling literature that established an art discourse in jazz aesthetics was shaped by ideas about race and blackness within energetic discussions about the “Africa” in the music. Taken together, these factors—the industries of music criticism and psychiatry and each of their roles in creating a jazz-art idea—provide compelling contexts for understanding some of the very powerful social ideas associated with Powell’s exploits as well as his reputation in American music history. The chapter helps to move my discussion beyond sound organization in order to explain the ways in which various social orders have inspired meaning in Powell’s music.

Much has been written recently about the “masculinist” discourses that have informed jazz’s public persona since its early years. Bebop, with its storied history of gladiator-style jam sessions/cutting contests patterned on athletic conquest, is legendary in this regard. Moving beyond this proving ground for musical “manhood” through spontaneous technical display, chapter 4 considers other factors. This key symbol of modern jazz masculinity can also be understood by engaging the histories of attitudes about a range of topics, including gendered ideas about musical instruments and commercialism, rhythmic coherence and the body, racial social orders, artistic heroic individualism, and the creative hierarchies assigned to both composition and improvisation. All of this is meant to deconstruct what constitutes jazz manhood or, in Powell’s specific case, to declare how the notion of his genius is a very gendered proposition from top to bottom. When situated within historical patterns of the larger American musical landscape, the jazz manhood complex takes on a more comprehensive import.

Chapter 5 provides a technical working through of the particularities of Powell’s contributions within the developing language of modern jazz. The presentation of this part of my discussion may challenge some readers not familiar with music theory. I have nonetheless tried to make the main ideas accessible to nonspecialists. Throughout the book, I show that modern jazz’s quite fascinating historiography has forwarded theories of its sound organization and cultural politics from the very beginning. Together with the details of Powell’s musical rhetoric, we witness a new style crystallizing through the recordings of a gifted yet challenged musician. As I stated above and reiterate throughout this book, with bebop, jazz expanded its social pedigree and became “art”; and it also morphed jazz itself into a genre distinct from other contemporary vernacular forms. This trajectory is easily traced from Powell’s earliest recordings to his later work.

In many ways, this book, one that centralizes the contributions of Bud Powell, details the collision of two vibrant political economies: the discourses of art and the practice of blackness. The “race” discourses that have formed a persistent source of controversy in jazz history are important (and certainly fascinating) enough to scrutinize here. As we will learn, the story of bebop is about the discourses of art and blackness meeting head-on and tussling it out in both musical and critical terms. Modern jazz occupies a singular position in American musical thought and scholarship. The so-called bebop revolution has been generally perceived as a radical break with “tradition,” particularly because of the perceived absence of social dancing in its aesthetic. This turn has signaled to some the music’s break with black vernacular expression and even the harsh realities of race in twentieth-century America. I argue, however, that the social energies resulting from this fissure spiral out into broader questions of artistic production in American society. As such, chapter 6 concludes with Powell’s move to Europe in an attempt to escape the complexities of race and art in America.