Читать книгу The Amazing Bud Powell - Guthrie P. Ramsey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

“Cullud Boys with Beards”

Serious Black Music and the Art of Bebop

Little cullud boys with beards

re-bop be-bop mop and stop.

Little cullud boys with fears,

frantic, kick their draftee years

into flatted fifths and flatter beers

that at a sudden change become

sparkling Oriental wines rich and strange . . .

Langston Hughes, “Flatted Fifths”

In her treasury of private memories, Bud Powell’s daughter, Celia, recalls her father as an uncomplicated man, “content with the simple things in life, not wanting much more than a meal and to play.”1 But in the public world where he established his fame, Powell cut a more challenging figure. His work represents, for many, a pinnacle of artistic achievement among the pantheon of brilliant jazz pianists. His relentless flow of musical ideas—their unsettling rhythmic disjunction; those explosive launches into beautifully crafted passages of push, pull, run, and riff, punctuated by the perfect landing at ferocious speeds—remains an inspiring, though intimidating, factor for pianists who come behind him. Indeed, his brilliance in the bebop idiom pushed jazz musicians of all stripes to high standards of performance that have rarely been matched. His contributions have been as germane to the modern jazz pianist’s training as Czerny five-finger exercises and Bach Inventions are to that of classically trained pianists. Despite his importance to jazz, he remains one of the music’s lesser-known figures. Yet he was a towering pianist who inspires awe and respect among those in the know.

As one of the select group of gifted mid-twentieth-century “cullud boys,” Powell can teach us much about what made his chosen idiom such a dramatic and poignant musical statement. Here and in following chapters, I discuss some of the themes and issues—musical and otherwise—that show how Powell’s bebop worked as a commercialized, racialized, gendered, and age-specific enterprise. Throughout his lifetime, jazz developed from a cultish, ethnic-infused vogue to the sound of American pop to a demanding avant-garde. Within this dynamic continuum of pedigree shifts, Powell’s work can also be seen as entangled in the aesthetic legacies of musicians such as Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, and Teddy Wilson, among others whose artistic lives helped to create a cultural space for the learning, practice, and dissemination of the art of jazz. At the same time, there are those who believe that we should retain the political edge that bebop once possessed as a stand-alone tradition. Eric Lott, for example, has lamented what he sees as the casual commercialization of a style that at one time represented the political and aesthetic avant-garde: “We need to restore the political edge to a music that has been so absorbed into the contemporary jazz language that it seems as safe as much of the current scene—the spate of jazz reissues, the deluge of ‘standard’ records, Bud Powell on CD—certainly an unfortunate historical irony.”2 Bebop is, indeed, an abundant site of expressive force.

Despite Powell’s brilliance as a pianist, composer, and innovator, his work remains a curious and understudied force in jazz history. Indeed, looking for Bud Powell involves a search through “cullud boys’ beards and fears”: it’s an investigation of the meanings embedded in all manner of styles, musical and otherwise, and how all of them signified in the world. Black male musicians of the 1940s streamed self-conscious ideas about who they were in the world through their art. In the flatted fifths, rhythmic disjunction, and sheer velocity of bebop convention, we can find Bud and his peers. But we also find him (and others like him) in other forms of representation, such as photography, and even in the other kinds of art that shaped his social world, such as poetry and the visual arts. In other words, we must examine the world into which Powell walked, a world in which life and musicianship challenged the post–World War II world on many levels. When we look for Bud, we sift through many riches.

THE MUSIC, THE WRITING, AND THE ART IDEA

Powell’s accomplishments invoke a generation of musicians whose innovations during the 1940s and 1950s are some of jazz’s greatest artistic triumphs. Through them, jazz became a bona fide “Art,” an expression that is considered by many to be an elitist music deserving formally trained devotees, a vigorous criticism, and a rigorous scholarship. With bebop, the accepted wisdom goes, jazz shed its populist impulses and moved up the cultural ladder. This book meditates on, among other things, this dramatic transition through the example of Powell’s musical contributions.

But “Great Art-Jazz” did not just happen; it had to pay its dues. In the scholarly world, for example, jazz would need to be analyzed with tools from beyond its immediate cultural borders. Jazz needed to be imbedded into the nineteenth-century Eurocentric notion of Great Art’s transcendence of the social and political “everyday,” and this move was a major hurdle for this body of music. And naturalizing the shift has been achieved primarily, though not exclusively, by the acts of formal musical analysis and written criticism. Let’s begin with “analysis,” by which I mean the study of musical structures as applied to specific works and performances.

One of the goals of formal analysis—to expose organic unity—is a musical value in which few major jazz musicians have expressed much interest. Enter Joseph Kerman, one of musicology’s progressive voices during the 1980s. This was a time when analysis of this kind came under increasing scrutiny as well as the time when the first dissertations on jazz began to appear in the field. Kerman argues that musical analysis is not a politically benign act, but “an essential adjunct to a fully articulated aesthetic value system”: western art music of the common practice period. Musical analysts extended their techniques to all of the music that they valued, and eventually to jazz, as part of this book exemplifies.3

At the same time, it should be understood that this brand of formal analysis, embedded as it is in nineteenth-century western European music history, has done little to raise the music’s prestige among the average jazz fan. Many Powell enthusiasts, for example, have never required musical scores or scholarly treatises to validate or affirm their devotion. His recordings, together with the lore, myth, and gossip that circulated around him, have sustained his reputation as one of jazz’s greatest, and indeed most mysterious, stars. Even casual knowledge of Powell and his exploits seems to anoint the jazz fan with insider, aficionado status. His work has remained important because of the extent to which jazz pianists have imitated his innovations, the scholarly analysis that it (and the work of his colleagues) has stimulated, and the devotion and awe that exists among his fans.

FROM THE JOOK TO THE CLASSROOM: BEBOP’S PEDIGREE OF BLACK MULTIPLICITY

Powell’s and his colleagues’ version of serious black music has often inspired the notion that theirs was an aesthetic in opposition to crass commercialism and, I would argue, to certain aspects of art discourses as well. A recurring theme in bebop literature (one that still shapes its reception), for example, presumes that modern jazz intentionally tried to sever itself from the entertainment business, from the “jooks” and nightclubs of its origins, and from its social legacy in the black “vernacular.” It is quite remarkable that such a diverse range of writers—music scholars, journalists, cultural critics—frame bebop’s profile in the same way: as a challenge to a diverse set of orthodoxies.

Musicologist Frank Tirro writes, for example, that bebop musicians attempted “to create a new elite.” The cultural critic Cornel West believes that “bebop musicians shunned publicity and eschewed visibility.” Likewise, journalist Nelson George argues: “The bebop attitude overrode any lingering connection to the black show-business tradition that turned any cultural expression into a potentially lucrative career (though eventually that would happen to the beboppers as well). Its adherents found it a higher calling than mere entertainment.” Music historian William Austin maintains that Charlie Parker’s “music required for discriminating appreciation as thorough a specialized preparation as any ‘classical style.’ . . . He stood for jazz as a fine art, knowing that this meant exclusiveness. . . . Thus with ‘bop,’ jazz met the difficulties that had bewildered critics of new serious music ever since 1910. The best work was so complex in harmony and rhythm that it sounded at first incoherent, not only to laymen but to professionals very close to it. Good work could no longer be discriminated with any speed or certainty from incompetent work.” English music critic Wilfred Mellers writes that although Parker’s roots in the black music tradition are evident, the “expressivity” of his rapidly paced music shares “affinities with the development in European art-music that was (contemporaneously) associated with Boulez, Stockhausen and Nono.”4

Writers who valued beboppers’ achievements borrowed critical rhetoric from the most prestigious and status-building model available to them—the modernist strain of western art music. But where did this leave Powell and his associates? Did the rhetoric of elite modernism serve well their aspirations?

One important writer believed it did not. Martin Williams, the influential jazz critic and compiler of the landmark anthology The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, writes that Charlie Parker helped renew jazz “simply by following his own artistic impulses.”5 Williams argues that bebop musicians made a self-conscious effort to change the social function of jazz. But he characterizes the result of this effort as a kind of “dream deferred,” questioning its success because although social dancing is, for the most part, not done to modern jazz, “for a large segment of its audience it is not quite an art music or a concert music. It remains by and large still something of a barroom atmosphere music. And perhaps a failure to establish a new function and milieu for jazz was, more than anything else, the personal tragedy of the members of the bebop generation.”6

Williams writes in the same essay that although Parker and others “repudiated what they thought of as the grinning and eye-rolling of earlier generations of jazzmen. . . . [they] courted a public success and a wide following that were defined in much the same terms as the popular success of some of their predecessors.”7 Naturally, the process of elevating bebop to this lofty new pedigree meant critically endowing the musicians themselves with artistic autonomy. But at the same time, Williams seems to recognize that jazz was not completely free from its social roots, that it seemed stuck between aesthetic discourses. So what is the truth about modern jazz’s pedigree?

Bebop musicians such as Powell did represent an elite group, and my discussion of his music will show that he merits this claim. But his elite status, like the pedigree of bebop itself, is quite a complex matter. At one time the word elite described “someone elected or formally chosen”; by the end of the nineteenth century, however, the term “became virtually equivalent with [the] ‘best.’”8 Writers have framed beboppers’ achievements in this latter sense, and more specifically, as an elitism within the framework of western art music. Yet I believe it is important to show that bebop retained powerful connections to black communal values and to the commercial, popular music industry. Ultimately, I wish to show through Powell’s music that any argument about bebop as fine art should take into account its dynamic relationship to art discourses, black culture, and commerce.

In order to parse this relationship, one has to move beyond the sonic. Bebop was, of course, sound, but it also embodied a look composed of the berets, goatees, and thick horn-rimmed glasses that were popular among the postwar “Museum of Modern Art set.”9 The clothing worn by the beboppers represented an “intellectualized” adaptation of the zoot suit, the dress code for World War II–era hipsters.10 Photographs of bebop musicians show that many chose to chemically straighten their hair in the “conk” style popular among many urban black males in the 1940s. Along with the look came an insider language. Trumpeter Miles Davis is only one of many who recalls that early beboppers cultivated a colorful vocabulary that grew out of black slang or jive talk, a popular dialect in the jazz world during the late 1930s and early 1940s.11

The bebop look and language gave the popular press an image to promote (or denounce) and lent more than a dash of human interest to the scene. Both Life and Ebony magazines featured articles in the late 1940s that focused primarily on these features. These seemingly peripheral aspects of bebop culture reveal much about the music’s political import. Robin D. G. Kelley argues that clothing such as the zoot suit (and variations thereof) does not carry a direct political statement in itself, but its cultural context renders it into a statement. Bebop musicians belonged to a larger underground culture of black working-class youth, in which the “zoot suit, the conk, the lindy hop, and the language of the ‘hep cat’ [were] signifiers of a culture of opposition among black, mostly male, youth.”12 Such acts have traditionally allowed the construction of a collective identity that challenges dominant stereotypes and forms insularity.

Consider, for example, Miles Davis’s account of Dexter Gordon coaching him in the art of “bebop hipness” in 1948. Gordon urged Davis to buy new clothes and to try to grow a moustache or a beard to affirm his affiliation with the bebop subculture—onstage and off. Davis recalls that after he had saved enough money, he purchased a big-shouldered suit that felt much too large for him. Gordon’s response upon seeing Davis in the suit resembles an initiation rite: “Now you looking like something, now you hip. . . . You can hang with us.”13 Bebop dress negotiated a musician’s identification as an insider of bebop subculture.

Kelley connects bebop’s sonic language to the hipster vocabulary that Miles Davis refers to above. Young black males, he writes, “created a fast-paced, improvisational language that sharply contrasted with the passive stereotype of the stuttering, tongue-tied sambo.”14 Dizzy Gillespie also recognized the relationship between the spoken words of the hipster and the musical rhetoric of bebop: “As we played with musical notes, bending them into new and different meanings that constantly changed, we played with words.”15 Gillespie’s “play” represents some important cultural work, firmly situating bebop within the priorities of black vernacular culture.

Moving back to the musical, how do we interpret bebop’s artistic pedigree through the lens of its sonic complexity? Did its intricate approach to harmony and rhythm and its virtuosic solos situate it outside the realm of black popular culture? Certainly this notion of complexity is crucial among those who believe that western art music is superior to other musical forms. Ethnomusicologist Judith Becker has argued that many believe “that Western art music is structurally more complex that other music; its architectural hierarchies, involved tonal relationships, and elaborated harmonic syntax not only defy complete analysis but have no parallel in the world.”16 And many jazz writers believe this sentiment to be true because a good deal of jazz literature assigns jazz prestige by arguing that it is just as complicated (and that it is complicated in the same way) as western art music. As I will show later, Powell’s music certainly embodies a good deal of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic complexity—so much so that it would seem to support a perception of bebop as art music. Yet we will also see how Powell’s early career in swing grounds the music in the repertory, not to mention the social histories, of other 1940s black popular music. (This is not a new point by any means; it is simply amplified in the specific case of Powell.)

Susan McClary has made clear how “within the context of industrial capitalism, two mutually exclusive economies of music developed: that which is measured by popular or commercial success and that which aims for the prestige conferred by official arbiters of taste.”17 The bebop-as-fine-art notion seems to have moved jazz from McClary’s first musical economy to the latter. The much-promoted idea that jazz is “America’s classical music” seems to suggest that philosophy. But successful music making in the United States has always depended on attracting and satisfying the needs of paying customers, and bebop was no exception.18 Beboppers worked under these assumptions, as Gillespie himself has pointed out: “We all wanted to make money, preferably by playing modern jazz.”19

The bebop movement as a whole conveyed a string of tensions: popular versus elite, commercial versus esoteric, vernacular versus cultivated. Bebop’s ability to communicate this aesthetic of multiplicity says much about the source of the music’s appeal in its own time, and even more about the nature of American music making. Some writers have tried to capture bebop’s essence in ways that indicate this multiplicity. Albert Murray links bebop, for example, to the Kansas City jam sessions of Charlie Parker’s youth: “Whatever they play becomes good-time music because they always maintain the velocity of celebration. . . . What you hear when you listen to Charlie Parker . . . is not a theorist dead set on turning dance music into concert music. What you hear is a brilliant protégé of Buster Smith and admirer of Lester Young adding a new dimension of elegance to the Kansas City drive, which is to say the velocity of celebration.”20 This kind of “driving celebration” is front and center in Powell’s music, as we shall see in much of the commentary about his music.

Music scholar Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., has said that “works of music are not just objects, but cultural transactions between human beings and organized sound—transactions that take place in specific idiomatic cultural contexts that are fraught with the values of the original contexts from which they spring, that require some translation by auditors in pursuit of the understanding and aesthetic substance they offer.”21 This book is ultimately about what transactions might have taken place during a Powell performance. How was the sound organized? In which specific contexts did Powell create his music, and in which contexts did it circulate? What aesthetic substance did he offer?

Powell’s contributions are, of course, best interrogated by exploring some of the ideas, activities, and discourses that have shaped our modern-day understanding of bebop. It should come as no surprise that old and new ideas about race percolate through many of these issues. Jazz is a powerful example of the many cross-pollinations occurring among the various cultural tributaries flowing into African American culture. As such, explanations of jazz that consider it essentially and solely “African” do not take into account history, human agency, or the fact that jazz shares a legacy with the European aesthetic value system. In other words, to analyze jazz, one must take seriously the breadth and diversity of African American culture, understand the qualities that make black music distinctive, take artistic human agency into account, consider jazz historiography, and, finally, consider the historical specificity of the work or artist in question. Numerous contested histories are dialogically and vibrantly present in both the art and the letters of modern jazz.

NOTES FROM A BLACK YOUTH UNDERGROUND—AND ITS CRITICS

The bebop movement began as the avant-garde music of 1940s black youth culture, much as Louis Armstrong’s music did in the 1920s and as hip-hop did in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As bebop drummer and pioneer Max Roach implores:

I often have to remind my cohorts, musicians of my generation, that rappers come from the same environment as Louis Armstrong—they came from the Harlems and the Bed-Stuys, the West Side of Chicagos. The rappers didn’t . . . [go] to the great conservatories or universities so they could deal with literature and “learn how to write poetry.” And Louis Armstrong didn’t go to the conservatory where he could learn to write music. And if he had, we wouldn’t have this great music that the world is listening to now. So thinking about that, I have to remind them that these guys are making history, like [John] Coltrane and Pops [Armstrong].22

Roach’s words not only grapple with the issue of youth culture, but also call up a fundamental tension involving “high” and “low” culture in the United States and the role of black youth in it all. Furthermore, they strike at the core of some key concerns involving the supposedly discrete and usually ahistorical boundaries drawn around this dichotomy. The sentiment behind statements such as “Jazz is serious,” “Jazz is not popular or commercial,” or even the now politically correct assertion—one that has been soundly refuted about western art music—that jazz possesses an “implicit universal intelligibility” begs rethinking.23

The idea that some music by its nature can transcend the commercial world and can thus become high art is an accepted tenet of the western art music tradition, particularly in its American context. But art music, in fact, has a commercial history. As William Weber has written: “We must regard the rise of the musical masters [Handel, J. S. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert] as an early form of mass culture—just early forms, of course, and therefore somewhat limited, but nonetheless clever, profit-seeking mass culture.” In other words, he argues that the “commercial exploitation of the masters was a major starting point of the modern music business.”24 These insights are not lost when considering Powell’s career in jazz. For example, every composition from Powell’s first leader session—with the exception of the two originals and “Indiana”—was considered a hit in the popular music industry at one time or another.25

The aesthetic, and therefore political, challenge leveled by this primarily black male youth culture went public in a highly visible and impacting way. The well-known story of bebop’s move from Harlem jook spaces to the wider commercial world of 52nd Street is, among other things, shot through with the politics of gendered language: commercial conquest, cultural territorialism, violence, and musical “cutting contests” are among the terminologies we encounter in various accounts. Bebop’s move to a “whiter” downtown geographic space represents more than simply a broadening of available venues for the music’s presentation. A huge aspect of bebop’s revolutionary, heroic status should be attributed to its ability to do precisely that: move “out of its place” geographically. As Katherine McKittrick has argued, “The ‘where’ of black geographies and black subjectivity . . . is often aligned with spatial processes that apparently fall back on seemingly predetermined stabilities, such as boundaries, color-lines, ‘proper’ places, fixed and settled infrastructures and streets, oceanic boundaries.”26 Following McKittrick’s model, I believe that bebop’s geographical journey, such as it was, altered the social processes of marginalization, concealment, and boundary making by revealing them as hegemonic strategies that organized race, gender, and class differentiation. In other words, it upset the “traditional geography,” an assumption pertaining to the ways in which we “view, assess, and ethically organize the world from a stable (white, patriarchal, Eurocentric, heterosexual, classed) vantage point.”27

New York in the 1940s was a hotbed of activity for all manner of black artists, but musicians seemed to be in the forefront of what might be called an after-hours renaissance. (We will see later that the emergence of new possibilities in artistic experimentation and black identities was not confined to the jazz world.) Bebop, like any commercially presented music, needed a venue, and Harlem’s nightlife in the early ’40s provided just that. Pianist Mary Lou Williams claims to know exactly how and why bebop got started. According to her, young black musicians often complained about not receiving enough credit for their contributions. Eventually, Thelonious Monk tried to start a big band to “create something that they can’t steal because they can’t play it.” Monk wrote difficult arrangements and began rehearsing in a basement. However, the group disbanded shortly thereafter because “the guys got hungry” and out of economic necessity had to seek employment with other bands: “Monk started as house pianist at Minton’s—the house that built bop—and after work the cats fell in to jam, and pretty soon you couldn’t get in Minton’s for musicians and instruments.”28

The story of how young maverick musicians congregated in afterhours jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse (and later at Clark Monroe’s Uptown House) is legendary.29 Jam sessions such those that took place at Minton’s and Monroe’s were “a mixture of recreation and business . . . musicians made contacts for future employment, held competitive ‘cutting contests’ to establish a pecking order, and took advantage of the isolation from public scrutiny to experiment with new techniques.”30 A crucial step in bebop’s progression toward economic viability was finding a place that would (1) give the musicians the freedom required to explore new musical territory, and (2) attract an open-minded and supportive clientele, a fan base. For several reasons, Minton’s created a suitable atmosphere for bebop’s early life. The club’s owner, Henry Minton, was a former musician who had, in the 1920s, run the Rhythm Club, an informal clearinghouse for black musicians.31 When Minton’s opened for business, musicians made it theirs. As the first African American delegate of Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians, Minton was sensitive to the financial and artistic needs of jazz musicians: he was generous with loans, he was fond of food, and, as an old acquaintance recalled, he “loved to put a pot on the range to share with unemployed friends.”32 As Ralph Ellison writes, Minton’s policy “provided a retreat, a homogeneous community where a collectivity of experience could find continuity and meaningful expression. Thus the stage was set for the birth of bop.”33

In January 1940, Minton hired musician Teddy Hill to replace Dewey Vanderburg as manager of his club. Hill, in turn, hired musicians whom he knew and encouraged jam sessions on the small bandstand.34 According to Kenny Clarke, arguably the first modern jazz drummer, Hill “never tried to tell us how to play. We played just as we felt.”35 Musicians’ eyewitness accounts provide valuable evidence of the cultural, and even musical, importance of the after-hours establishment to jazz life. Williams stresses that Minton maintained a down-to-earth atmosphere, believed in keeping the place up, and was constantly redecorating. “And the food was good. Lindsay Steele had the kitchen at one time. He cooked wonderful meals and was a good mixer, who could sing awhile during the intermission.”36 Miles Davis remembers that it did not cost anything to get into Minton’s unless you sat a table, and that cost around two dollars. He describes Minton’s as a supper club with neat white linen cloth tables complemented with little vases, where the clientele was well dressed. And Davis recalls that a great black woman cook named Adelle prepared the food.37 Another attraction of Minton’s was the “Monday night down home dinners” for the cast of current shows at the Apollo Theater.38 To away-from-home musicians such as Davis, the Minton’s milieu exemplified good food, music, atmosphere, stylish dress, and remembering the cook’s name. It was the communal sharing of urban African American culture.

The atmosphere of clubs such as Minton’s made Harlem a hothouse for early bebop and other forms of entertainment aimed at local black audiences. Harlem offered these musicians “a rediscovered community of things they had left behind: feasts, talk, home.”39 And, as Malcolm X observed, Harlem’s nightlife appealed to many who did not live there when he arrived in the early 1940s: “Up and down along and between Lenox and Seventh and Eighth Avenues, Harlem was like some technicolor bazaar. Hundreds of Negro soldiers and sailors, gawking and young like me, passed by. Harlem by now was officially off limits to white servicemen. There had already been some muggings and robberies, and several white servicemen had been found murdered. The police were also trying to discourage white civilians from coming uptown, but those who wanted to still did.”40 Fifty-Second Street, bebop’s new “home” after 1945, was starkly different. Leonard Feather once described the clubs there as having no identity, sleazy, discriminatory, with very small tables and watered-down drinks: “There was nothing to them except the music.”41 Perhaps candid observations by Davis and Gillespie, respectively, comparing Harlem and 52nd Street sum up best the tenor of each space: “It was a wonderful time. But 52d St. was better. Uptown we were just experimenting. By the time we came down[town] our ideas were beginning to be accepted. Oh, it took some time, but 52d St. gave us the rooms to play and the audiences.”42 Gillespie’s statement contrasts strongly with Davis’s:

It was Minton’s where a musician really cut his teeth and then went downtown to The Street. Fifty-second Street was easy compared to what was happening up at Minton’s. You went to 52nd to make money and be seen by the white music critics and white people. But you came uptown to Minton’s if you wanted to make a reputation among the musicians . . . After bebop became the rage, white music critics tried to act like they discovered it—and us—down on 52nd Street. . . . But the musicians and the people who really loved and respected bebop and the truth know that the real thing happened up in Harlem, at Minton’s.43

Wonderful times with rooms and audiences, compared to respect among peers and the real thing—a distinct dichotomy produced in two very different cultural spaces. Harlem was a woodshed. It was a rite-of-passage experience in which bebop musicians came of age. Fifty-Second Street, on the other hand, represented the larger marketplace, the media, and commercial industry. With proper exposure on the Street, an artist could gain access to record contracts and prestigious concert bookings in halls that previously had been off-limits. A bebop musician’s career soon depended on having others manage or navigate this move. Thus, bebop’s journey to 52nd Street represented another important rite of passage: it became a mainstream business. The economic reality that bebop musicians could not sustain careers in Harlem is an important point to keep in mind while reevaluating the notion that bebop was somehow exclusively anticommercial.

Bebop musicians found themselves turning to audiences outside Harlem for wider recognition. They could not achieve lucrative careers away from the white publications or from downtown audiences. Furthermore, they could not help but care what critics wrote about their music, nor could they thrive economically without them. Miles Davis noted that critics became keenly interested in bebop only after musicians began playing on the Street, which provided them with money and media exposure. Nightclubs such as the Three Deuces, Kelley’s Stables, the Onyx, and the Downbeat Club became more important to bebop’s survival than Harlem clubs because of the economic opportunities available in midtown Manhattan.

Patrick Burke’s study of the Street’s social history represents it as a complex, contradictory space where one could find “the most conventional forms of racial discrimination and stereotyping” existing side by side with “a radical trend toward racial integration.” These clubs were among the first to feature integrated bands and audiences, and by the 1940s some of them had become the city’s first black-owned nightclubs.44 This social frontier in race relations highlighted the fear of miscegenation as once segregated audiences began to fill with black (and white) hipsters (or “zombies,” as they were also called). Zoot-suited, long-haired, and reefer-smoking, these black hipsters quite publicly undermined the Street’s entrenched “white bachelor subculture” by openly dating and showing authority over white women. As Burke points out, not all blacks and bebop musicians were hipsters on the Street, and some of the musicians were white. But the bebop movement was closely associated with this hipster subculture, and as Burke, Ingrid Monson, Robin D. G. Kelley, and other observers have noted, its reputation turned on troubling primitivist notions of black masculinity.45

As real or imagined sexual threats to white superiority, black bebop musicians became embroiled in a battle of subcultures, sometimes marked by violent episodes. Miles Davis, for example, recalls a specific kind of racial tension surrounding bebop’s Midtown move—one that was an age-old and volatile reason for Jim Crow in the first place. For him, the increased visibility of black male musicians dating white women in Midtown, together with the insider’s dress code and colorful vocabulary, fanned the flame of intolerance: “[Whites] thought that they were being invaded by niggers from Harlem.”46 Uptown invaded Midtown with a dissonant, polyrhythmic, and uncompromising vengeance. Indeed, bebop’s beginnings in Harlem’s insular woodsheds and heroic cutting contests, together with the language of conquest used to characterize its move to the commercial and sexual territories of the Street, sharpened the music’s experimental, masculinist edges. But bebop was only one side of a multifaceted world of black artistic experimentation at midcentury.

CRITICAL INQUIRY: JAZZ CRITICISM AT THE CROSSROADS

Although scholars have been among its most ardent advocates, the idea that jazz is an art music did not first emerge in the plodding pages of academic journals, but rather in a messy, noisy, free-for-all atmosphere in which musicians, critics, entrepreneurs, club owners, and publicists battled for cultural turf, prestige, and a slice of the commercial pie. Motivated to varying degrees by self-interest, artistic experimentation, and the politics of American social life, these historical actors established the jazz-as-art idea in what Bernard Gendron has called an “aesthetic discursive formation.”47

Jazz critics were especially dominant forces in these discourses—many of which borrowed from the western art music world—that laid the groundwork for jazz becoming serious art and, with that, a genre separate from other popular music styles. It should be noted that jazz criticism was a primarily white enterprise in the 1940s, and the bebop musicians themselves primarily African American.48 The amalgamation of social worlds is only part of the story’s complexity, however. Other aspects include primarily journalistic debates in which key ideas—usually oppositional—established a conceptual framework in which jazz would transform its pedigree from folk and mass culture into art. Such debates investigated genres and brand names; art and commerce; folklore and European high culture; progress and the new; standards, techniques, and schooling; affect and antics; and fascists and communists.49 Many of these ideas formed binary constructions that galvanized the debates. (As we learned above, even the early cultural spaces in which bebop could be heard can be viewed as a dichotomy between the after-hours Harlem and 52nd Street nightspots.)

As Gendron points out, two literary factional wars in the 1940s, the first between swing and the revivalist Dixieland movement, and the second pitting bebop against the two former styles, created a new way to look at jazz. What emerged from this war of words was “a set of agreed-upon claims about the aesthetic merit of various jazz styles . . . [and] a grouping of concepts, distinctions, oppositions, rhetorical ploys, and allowable inferences, which as a whole fixed the limits within which inquiries concerning the aesthetics of jazz could take place and without which the claim that jazz is an art form would be merely an abstraction or an incantation.”50

Thus a language developed for valuing jazz as art, a strategy contingent upon the notion of the music’s organic growth and development.51 In this framework, a boundary between jazz and other popular forms was drawn. For Gendron, bebop represents an early form of postmodernism because its emergence marked the first time that “popular culture abandoned its previously passive, almost unwitting, engagement with high culture, to become an initiator and even an aggressor.”52 This claim is instructive, especially in its implications for a gendered reading of bebop and jazz’s generic shift, as we shall witness below.

The musicians in this saga negotiated this emerging, contentious art world primarily through their sonic experimentations, although Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, the two iconic figures of early bebop, issued public statements in interviews that critics used to validate one position or another. How can we interpret and understand their cultural work— indeed, their insurrection—as masculinist, aggressive, and transformative? The following commentary identifies some of the ground on which these meanings were fought out.

The journalists who wrote about bebop left behind a trail of print in the popular and trade press documenting a colorful and instructive controversy. With titles such as “How Deaf Can You Get?” (1948) and “Do You Get It?” (1949), many of these articles range in tone from bewilderment to hostility to outrage at bebop. In a record review, Charles Miller writes as if peer pressure had forced him to deal with the new music: “Although I’m less than enthusiastic about a style of jazz called bebop, I feel that it’s worth writing about because it’s attracting an increasing number of listeners and because it might some day make more sense than it does now.”53 His description below, particularly his choice of such words as “weird,” “neurotic,” and “foreign,” allows us to experience a bit of the distancing effect bebop had on some contemporaneous listeners. Interestingly, these terms function—perhaps unwittingly—to emasculate the work of bebop musicians, especially the embedded innuendo that they were not involved in serious creative acts and seemed to be just “fooling around”: “Bebop isn’t easy to define, but I think it’s safe to call it highly experimental. Bebop musicians like to fool around with weird sounding chord effects and unusually complex melodic and rhythmic patterns, producing stuff that’s comparatively foreign to many ears. For my money, it’s an intensely neurotic style, and except for occasional passages that show imagination and beauty, I want no part of it.” Miller goes on to rehearse a wisecrack about the style: “Bebop is just a bunch of guys covering up their mistakes.”54 Wilder Hobson adopts a similar tone when reviewing a Dizzy Gillespie recording, using the opportunity to expound on the virtues of earlier jazz and to ridicule bebop. While generally dismissive, he compliments bebop musicians for being “incredibly agile” and reluctantly admits that the recording has a certain arresting and eerie quality.55 In his listening experience, bebop was “a miss.”

The mainstream press also took note of the controversy. A Time article from 1948, “Bopera on Broadway,” about the Royal Roost, a New York club that was among the first to feature bebop exclusively, notes: “Bebop has been around for seven or eight years, and something of a fad for two, but experts still disagree as to what it is, and whether it will last.” To this writer, the music was “shrill cacophony” and “anarchistic.”56 The article also mentions that clubs featuring bebop customarily maintained a no-dancing policy, which forced audiences either to listen to or ignore the music. A Newsweek article of the same year, “B. G. and Bebop,” responding to Benny Goodman’s experimentation with bebop in his group, polls several of Manhattan’s leading jazz critics. The most negative comment comes from the influential jazz critic and entrepreneur John Hammond, then vice-president of Mercury Records: “To me bop is a collection of nauseating clichés, repeated ad infinitum.”57

By 1949, the public recognized Gillespie and Parker as leading figures in bebop, and the musicians issued public statements about the music in the press. When he was asked the question “What is bebop?” Dizzy Gillespie answered that it is “just the way I and a few of my fellow musicians feel about jazz. It’s our means of expressing ourselves in music just as, years ago, the Chicagoans and the Dixielanders expressed themselves.”58 At face value, his words seem to defend his artistic right to experiment, to achieve artistic manhood. But he was probably also connecting bebop to earlier, more popular styles because he was fighting to keep his career afloat and his bank account in the black. Gillespie, known for his demonstrative, antic-filled stage manner, had a modernism that was an unabashedly commercial endeavor.

For his part in the “debate,” Charlie Parker chose another tactic. In Oedipal fashion, he claimed that bebop had developed apart from the older styles of jazz, stressing his music’s distance from the musical past.59 Bebop, for Parker, was rhythmically radical, and he wanted to wear that distinction on his sleeve. Gillespie countered in the October 7, 1949, issue of Down Beat that Parker was wrong: Bebop was an interpretation of jazz and certainly a part of its tradition.60 This debate was about more than a casual exchange of abstract ideas for these musicians. They were engaged in a public struggle for their commercial lives and, by extension, their social lives, in a context in which they exercised little control over the public meaning and discursive dissemination of their work. The critics, although not culturally powerful outside of the jazz community, ruled over these domains.61

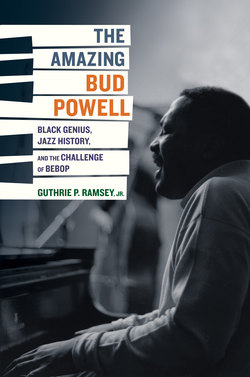

Like jazz criticism, photographs of jazz musicians became an expressive domain that informed the ways in which bebop’s pedigree circulated in the public sphere. The diligence and artful sensibilities with which photographers began to frame jazz musicians had political as well as commercial implications. As Benjamin Cawthra argues: “Jazz photography . . . did its best to bring jazz into a mainstream of American culture. In this mainstream, jazz could function as an ambassador for American values while subtly—but with increasing intensity over time and in the eyes of particular photographers—offering a critique of those values via the presentation of African American virtuosity. Jazz itself existed as a kind of critique of a society divided racially, and its photographers made that critique visible while publicizing and selling the music.”62 The photographs of Bud Powell in this book allow us to see an influential modality in which the idea of his genius—and, by extension, bebop’s artistic constitution—was consumed by his public and in history. Indeed, the photographs, Cawthra insists, “shaped that history, making arguments through visual means for the significance of African American musical culture, the meaning of jazz in American history, and the moral necessity of a politics of equality, even though these goals themselves were complicated by the racial dynamics of jazz itself.”63 Bebop visuality, it seems, asserted just as much force in American culture as the music’s sonic aspects.

Bebop has certainly traveled considerable critical distance since the days when it was described as “a bunch of guys covering up mistakes” and as “shrill cacophony” and “nauseating clichés.” While certainly rooted in the bodily excesses of the dance floor, Powell’s music has risen to the lofty status of “head” music. Even the hip dress and speech patterns of bebop musicians, treated routinely in sensationalist terms by the contemporaneous press, seem benign and safe by today’s standards.

RACE, COMPLEXITY, AND “THE” JAZZ AUDIENCE

A standard axiom of the western art music tradition is the sheer effort it takes for audiences to comprehend the best of its works. In an article published during bebop’s early years (1941), Theodor Adorno compares the cultural work of “popular” and “serious” audiences, especially as they relate to the notions of simplicity and complexity:

Listening to popular music is manipulated not only by its promoters but, as it were, by the inherent nature of this music itself, into a system of response mechanisms wholly antagonistic to the ideal of individuality in a free, liberal society. This has nothing to do with simplicity and complexity. In serious music, each musical element, even the simplest one, is “itself,” and the more highly organized the work is, the less possibility there is of substitution among the details. In hit music, however, the structure underlying the piece is abstract, existing independent of the specific course of the music. This is basic to the illusion that certain complex harmonies are more easily understandable in popular music than the same harmonies in serious music.64

Jazz, in Adorno’s mind, belongs to the popular realm. He does recognize, however, that it possesses qualities not found in other popular genres. But to him these qualities only camouflage jazz’s inherent banality: “In jazz the amateur listener is capable of replacing complicated rhythmical [sic] or harmonic formulas by the schematic ones which they represent and which they still suggest, however adventurous they appear.”65 (If what Adorno says is true, it seems to suggest a certain level of sophistication on behalf of jazz audiences that largely goes unnoticed.)

Establishing the point that jazz is not popular has composed an important part of the jazz studies agenda over the last thirty years. In doing so, jazz scholars have ignored or usurped the varied nature of the jazz audience. One strategy has been to make the jazz audience appear to have the same goals and tastes that western art music audiences do. This strategy invariably attempts to place jazz in the realm of high art.

In the fifth edition of his Jazz Styles, a popular “jazz appreciation” textbook, Mark Gridley’s didactic explanation of why jazz is not “popular music” shows some of the problems implicit in attempts to reify the perceived boundaries between high and low culture: (1) “jazz musicians represent a highly versatile and specially trained elite whose level of sophistication is not common to the population at large”; (2) jazz “is appreciated for its esthetic and intellectual rewards, and it is approached with some effort”; and (3) jazz “requires a cultivated taste.”66 All of Gridley’s statements are true. But they rub against his other ideas, designed to put the undergraduate music appreciation student at ease: “Jazz can be a lot of fun to listen to. But some people miss that fun because they let themselves be intimidated.”67 In my view, however, jazz audiences are dynamic entities that defy static representation, and they invite a reconfiguration of terms such as sophistication, taste, intellectual, cultivation, and even fun as they concern the reception of jazz.

Naturally, this suggests that a history of “the” jazz audience begs to be written.68 Such a study could help to clear up some commonly held misconceptions, among them that after the advent of bebop, black citizens shunned jazz in favor of rhythm and blues. Such sentiments fail to acknowledge the diversity and complexity of African American audiences, especially in the postwar period. Black audiences have continually demanded that musicians be avant-garde with regard to their treatment of traditional musical materials.

Moreover, history also proves that for many reasons, African Americans have generally shown little interest in preserving idioms for posterity’s sake. That attitude toward music making has produced a huge body of music, some of it among the most influential and widely appreciated music of the twentieth century. Susan McClary has coined the term terminal prestige to explain the results of certain contemporary, academic composers’ view that audience approval is a symbol of artistic compromise.69 Some writers have suggested that bebop musicians’ temperaments resulted in the same terminal prestige for modern jazz—especially among African American audiences. What these accounts fail to acknowledge, however, is that the black audience’s continual demand for an avant-garde necessarily positions every musical idiom, artist, and genre as a candidate for supplanting. Such was the case with swing at the appearance of bebop, and with bebop at the advent of rhythm and blues.

There also remains a huge misunderstanding about how black audiences “take music seriously.” For many scholars, critics, and other observers, this confusion has led to the assumption that whites are better caretakers of black music making than blacks themselves could be. Martin Williams wrote the following passage in 1964, a racially contentious moment indeed, as a challenge “to the next man who does a sociological study of jazz”:

Now everyone knows, musicians themselves aside, that it had been white men, by and large, who have taken jazz seriously, written its history, cataloged its records, criticized its players, and called it an “art.” One might easily say that the mode of the white man’s education prepared him to treat this musical activity called jazz in that manner, since he had been trained to treat painting, architecture, literature, and music in a similar manner. Whereas fewer Negroes have been exposed to that sort of education, to that sort of treatment of artistic endeavor, and therefore did not think in those terms. Or those who had been, again, were brainwashed against jazz by middle-class standards.

Williams notes that even black jazz musicians agreed with him: “Louis Armstrong often said that, throughout his musical life, his work was better attended and better appreciated by white men than by members of his own race. And Duke Ellington did not even begin to discover the size of his talent until he started to play at the Cotton Club for audiences that were predominantly white and where Negroes knew they were not welcome.”70

Williams’s argument raises two points worth pursuing here. First, his two examples highlight the need to understand the impact of black jazz audiences on jazz musicians’ careers. In that light, Williams’s conclusions raise important questions. Was Armstrong far past his vogue, at least as far as black audiences were concerned, when he expressed the sentiments above? In which ways did whites demonstrate their “appreciation”? Could the fact that white audiences at the Cotton Club were able to provide the financial support necessary for Ellington’s musical growth be a factor in his “epiphany”? If so, then Williams’s concerns are more economically based than they are racial. Can the same patterns be seen in the bebop audience?

The second point concerns the role of cultural values and hierarchies. During her tenure in the Billy Eckstine Orchestra, Sarah Vaughan witnessed bebop’s impact on audiences. Her comments imply that black audiences paid their highest compliments by dancing: “We tried to educate people. We used to play dances, and there were just a very few who understood who would be in a corner, jitterbugging forever, while the rest just stood staring at us.”71 Mary Lou Williams also recalls that bebop, for a time, pleased dancers where the space allowed: “Right from the start, musical reactionaries have said the worst about bop. But after seeing the Savoy Ballroom kids fit dances to this kind of music, I felt it was destined to become the new era of music, though not taking anything away from Dixieland or swing or any of the great stars of jazz.”72 These examples show the necessity of historizing statements about the tastes and reactions of African American audiences (or any audience), because these sentiments are dynamic ones that constantly shift. In fact, Lawrence Levine shows that jazz generally enjoys an audience in much the same way that opera in mid-nineteenth-century America did: “Like Shakespearean drama, then, opera was an art form that was simultaneously popular and elite. That is, it was attended both by large numbers of people who derived great pleasure from it and experienced it in the context of their normal everyday culture, and smaller socially and economically elite groups who derived both pleasure and social confirmation from it.”73 In other words, whether one writes histories, catalogues records, founds archives, or “jitterbug[s] forever,” there are many ways to get at the meaning and the history of cultural expressions.

The tensions surrounding any simplistic view of these points can be illustrated by a recent visit I made to Jazz at Lincoln Center. Situated atop an upscale mall in midtown Manhattan, its stunning facilities have become symbolic of jazz’s century-long trek from brothel Muzak to artistic artifact. An in-house repertory ensemble keeps the flame of previous jazz styles alive while a pristine, smokeless nightclub provides current jazz stars an unusually plush and inviting setting in which to share their music before a breathtaking backdrop of Manhattan’s skyline. Clearly, the boundaries between art and commerce are laid bare here, in relaxed splendor. Even the most cynical “pro-folk” cultural critic is grateful to witness jazz’s ascent to such auspicious surroundings.

We find similar tensions in discussions about the nature of the jazz sound itself. Martin Williams, for example, believes that Charlie Parker was not “a great composer.” Parker’s best composition, he asserts, is “Confirmation,” primarily because of one quality it possesses: “a continuous linear invention,” or, in other words, its complexity.74 (Williams has plenty of distinguished company who share his preferences.) Whenever jazz seemed to stray from certain ideals held in western music, critics have responded hastily. The history of jazz has seen more than its share of calls for greater motivic unity in solos, praise for longer forms in composition, denunciations of repetition, and appeals for formalized concert decorum. Of course, it has seen calls for “back to the basics”/“down-with-elitism” movements as well.

The suggestion that jazz needed a transfusion from the western art music tradition is curious, considering the music’s debt to European traditions in the first place. Certainly Powell’s early training in classical music provides an obvious case in point. Yet on a deeper level this privileging of the “West” points to the need to understand the complexity of the relationship between African American culture and modernism. Elsewhere, I have employed the term Afro-modernism to describe a specifically African American response to modernity, especially in the United States. Its concerns are not just aesthetic, but also social, political, and economic. Expressive practices such as music, photography, visual art, poetry, and literature both reflect and shape these domains. All these factors intersect in the world of one musician: Powell.

SCHOOLING BEBOP

In the 1990s, during jazz’s new academic surge, Scott DeVeaux summed up the prevailing view of bebop’s new modernist pose:

The transition from swing to bebop is more than the passage from one style to another. Bebop is the keystone in the grand historical arch, the crucial link between the early stage of jazz and modernity. Indeed, it is only with bebop that the essential nature of jazz is unmistakably revealed. There is an implicit entelechy in the progression from early jazz to bebop: the gradual shedding of utilitarian associations with dance music, popular song, and entertainment, as both musicians and public become aware of what jazz really is, or could be. With bebop, jazz finally became an art music.75

I add that with bebop, jazz became a genre separate from other popular music styles, complete with a new social contract with the public, cultural institutions, and musicians.

This perceived change in pedigree has inspired numerous speculations on the art of the politics and on the politics embedded in the art of bebop, with writers coming down on one side or the other of the aesthetics-versus-politics divide. These cultural differences are seen clearly in the language used to argue for this or that position in these debates. If gender is about power, with the ideals of male and female representing different points on a continuum of prestige, then bebop has existed as a slippery, transgendered discourse, at various times being assigned the mantle of great, masculinist art, and at others relegated to “weaker” cultural positions vis-à-vis western art music. Yet certainly one gets the impression from DeVeaux’s characterization that, finally, through aesthetic discourse, jazz had “manned up.”

Although bebop is recognized as black music, its pedigree has been elevated as the work of an elite class of musicians, akin to modernist composers of the western art music tradition such as Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Webern. Subsequent musicians who worked in the style known as free jazz inspired similar comparisons to this group of avant-garde, experimental composers. Powell’s music (and that of other beboppers) has achieved, in some respects, the status and appeal that cultural critics and theorists desired for black classical musicians such as William Grant Still, whose activities blossomed during the Harlem Renaissance. In fact, African American composers of classical music still do not receive the attention they deserve in the broad scheme of American music studies. Jazz musicians, on the other hand, have become crucial figures in these histories.

The popularity of jazz in the curricula of American colleges and universities is a reliable measure of the respect it now attracts. Performing ensembles and theory and history courses bring serious study to the music once thought unworthy of sustained consideration. Universities bestow honorary doctorates on jazz musicians in this new “jazz age,” and their names are cited among the same cadre of honorees as prominent scientists, physicians, educators, artists, and scholars. Yet for all of its sonic riches and rewards, the music alone accounts for only part of this pedigree shift. Writers—both critics and scholars—have played a key role in establishing the music’s new and improved social profile.

Jazz criticism as an enterprise has appeared in many guises. Truly international in scope, its expressions are myriad, ranging from publicists’ ravings in trade journals to freelancers’ rants about the latest pressing controversy. From the French critic Andre Hodeir to the black nationalist Amiri Baraka, from the southern new criticism of Martin Williams to the Big Apple poetics of Gary Giddins, from the staunch and testy prose of Stanley Crouch to the leftist politics of Nat Hentoff, jazz criticism has constituted an eclectic bundle of journalistic impulses. Taken together, these writings brought to the American public a sustained level of critical and aesthetic discourse about a music that had at one time struggled for widespread aesthetic legitimacy.76

For its part, jazz scholarship—its most current iteration is dubbed “the new jazz studies”—is now a bona fide area of the music subdisciplines and appears across an interdisciplinary spectrum of humanities fields, including English, history, and American studies. Partly as a result of the deconstruction of the canon and partly inspired by the 1980s jazz renaissance (replete with “young lions” dressed in business suits, new recording deals, and historical classics reissued on compact disc), the 1990s surge in dissertations, scholarly monographs, and articles changed forever how the music was perceived: as a serious artistic pursuit on par with other fine arts. The new jazz studies insists that jazz music is much more than an abstract set of technical principles, chord changes, rhythms, and organizations; it is also a cultural phenomenon whose scope of influence can be experienced in the visual arts, literature, dance, and film.77

Since the 1990s, jazz historians have moved beyond the aesthetics of universalism that once ruled jazz academic discourse and led us into richer readings of the topic. A number of scholars (the work presented below is merely suggestive of the available studies) have taken on the challenge of bebop specifically, producing nuanced interpretations of the musicians, the music, its audiences, and the historical contexts that produced them. The most broadly conceived and sweeping of these bebop studies is Scott DeVeaux’s blockbuster study The Birth of Bebop (1997). DeVeaux writes about the emergence of bebop style by attending to musical analysis and to the political economy of the jazz world during the years that bridged the swing and bebop eras. When the book won the American Musicological Society’s best book award in 1998, it sent a resounding signal to this corner of the academic world that jazz studies was viable, attractive, and rigorous. Other scholars tightened their focus around more specific topics. Ingrid Monson’s Saying Something (1996) penetrates and explains the social meanings generated within the improvisatory setting of the typical rhythm sections of modern jazz ensembles. Her ethnographic work weds the social theories of anthropology to musical analysis and the broader field of cultural studies, the latter of which had rambled through the humanities during the 1980s and 1990s. In What Is This Thing Called Jazz? (2002), Eric Porter takes a discerning look at modern jazz musicians as bona fide intellectuals—not as naturally gifted noble savages, but as self-conscious participants in both their creative work and the critical discourses that surround it. Porter’s American studies–styled readings of a multiplicity of texts illuminate how bebop opened a space in the popular sphere for aesthetically challenging black music, serious black audiences, and virtuoso black musicians. In two of its chapters, Bernard Gendron’s Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club (2002) focuses on critical discourses during the bebop era and argues that modern jazz represents a postmodern turn in the historical relationship between high and low culture. By this argument, Gendron means that, in his view, postmodernism emerged when popular culture (in this case, bebop) became the unprecedented aggressor in the historical high and low cultural exchanges that had occurred throughout the twentieth century. Eddie Meadows’s Bebop to Cool (2003) contextualizes bebop within the black liberation struggles in all its stripes—from Marcus Garvey to Islam. Also narrowly focused on African American reception, my Race Music (2003) discusses the social energies that were exchanged between musical cultures such as bebop and historical African American audiences to determine the extent to which each symbolizes specific responses to modernism. Works by David Ake, Ingrid Monson, Farah Griffin and Salim Washington emphasize cultural studies informed readings of bebop—what the music teaches us about the larger social world in which it circulated. And Robin D. G. Kelley’s majestic biography of Thelonius Monk is a model for understanding how the historical bebop musician impacted the entire American musical landscape.78

All things told, jazz criticism and scholarship have helped to usher the music into a new age of quasi-respectability. Coupled with corporate interest in promoting this new profile, it would seem that we are in the sway of a new orthodoxy that might be called Jazz, Inc. With respectability as one of its core impulses, Jazz, Inc., embodies all of the tensions and contradictions of late capitalism, a state in which a discourse attempts to marshal and stabilize styles, critiques, and theories into something manageable and consumable even as it exploits its perceived marginal status. The emergence of jazz studies in the academy developed in the context of the larger movement of multiculturalism. This leftist-inspired 1990s shift allowed “people of color culture” to gain ground as subjects and objects of study in the academy. And, of course, commerce has played an important role here. Institutional support, in particular funding from foundations, provides financial backing for symposia, endowed chairs, publications, concert series, and artist-in-residence posts—all the trimmings and trappings of an established art form.

This new jazz orthodoxy is reminiscent of similar moves in other areas. The late painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example, rose to prominence in the 1980s. He burst onto the scene first as a marginal, self-styled graffiti artist. Later, by virtue of his outsized talent, growth, and ambition, he quickly became an art star whose works today command “some of the highest prices of any African American artist in United States history.” Basquiat’s important 2005 touring retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, was sponsored by none other than JP Morgan Chase.79

Closer to jazz’s home, Wynton Marsalis, a gifted jazz musician who emerged as a young titan in the early 1980s, has become a notable ambassador of Jazz, Inc., in his highly visible roles as the artistic director and philanthropic pitchman for Jazz at Lincoln Center, a powerful institution with a reported $31 million operating budget, supported by both sponsors and ticket sales. A newcomer to the Lincoln Center complex, jazz first became a strong presence there in 1987 when it took its place next to opera and concert music, genres with much longer American histories of philanthropic backing.80 These “from margins to center” narratives—be they about specific artists or entire genres— did not occur in vacuums, but within a political economy that is constituted by the obvious suspects of race, class, gender, commerce, and other discourses that always mediate interactions between the powerless and the powerful.

Now we can begin to examine the relationship between the historic figure (Powell) and the “historiographic,” the world of histories of and ideas about expressive culture. I seek to understand Powell and his music from many perspectives and interpretive positions and with many tools, an exercise that is in sync with other recent examples of contemporary jazz scholarship. These studies, as John Gennari notes, investigate how “jazz has been imagined, defined, managed, and shaped within particular cultural contexts. [They consider] how jazz as an experience of sounds, movements, and states of feeling has always been mediated and complicated by peculiarly American cultural patterns, especially those of race and sexuality.”81 With an ambitious model of investigation in mind, this study of Powell illuminates his life’s work, but also takes this opportunity to address larger issues in African American music.