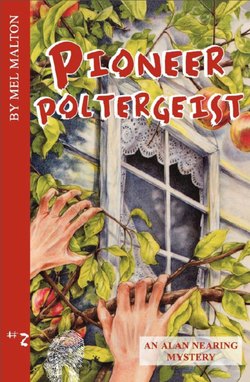

Читать книгу Pioneer Poltergeist - H. Mel Malton - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеHow can two goats and a donkey produce so much . . . manure?” Alan wanted to use a stronger word for the stuff, but he was saving it for when he was mad enough. He blew out a breath to get a flop of hair out of his eyes and took a better grip on his shovel.

“It’s just grass and mulched veggies,” Ziggy said. “Think of it as backyard compost.”

“Still stinks.”

It was their first day on the job as go-fers at the Kuskawa Pioneer Village Park.

“Go-fer means you’re the one who goes-fer things,” Alan’s mother had explained. “Kind of a messenger and helper on the site. And you’ll be wearing pioneer costumes, like in a play. It’ll be fun.”

It had sounded like a good idea at the time. They were going to be paid for the work, even though they were only eleven, and anything had to be better than mowing lawns, which is what they usually did to earn back-to-school money. So, Alan and his friends Ziggy and Josée were spending the last two weeks of August working at the park, before school started.

Their job, as explained when they had arrived that morning, was simple. “Just make yourselves useful,” the staff supervisor had said. She looked like someone’s saintly old grandma, in a long dress and shawl, but she obviously ruled the place. “All the staff have jobs to do around here,” she had said, “and they’ll be glad of the help. They’ll send you back and forth with messages, too. We don’t use walkie-talkies here, except when there’s trouble. They ruin the atmosphere.”

Alan and Ziggy had been given overalls, boots and straw hats. Josée was handed a long skirt and a sunbonnet.

Now, Alan was working himself up into a temper. “I thought we would be doing things like chopping wood and carrying axes around,” he said. “Maybe grabbing a nap under a tree.”

Josée got to sit in a shady courtyard, helping a lady make candles. Alan and Ziggy, however, were asked to muck out the animal pens with wooden-handled shovels—the old-fashioned way, to show the tourists how it used to be done. In the evening, when the park was closed, the maintenance guy, Sheldon, would clear out the pens properly with a MiniCat tractor, but the boys were to do as much as they could by hand, for show. And they weren’t allowed to go near the tractor.

“This is my baby,” Sheldon had said when he was showing them around the maintenance hut.

“I can see that,” Alan had said, and Ziggy had poked him. The machine was hidden under a blanket, like a horse. It was orange and chrome, gleaming with polish and oil, and Sheldon was patting the side of it. He kept the keys on a chain attached to his pants, so they knew he was serious about the No Touch rule. Alan figured they wouldn’t be getting tractor-driving lessons any time soon.

Instead, they were shovelling poo.

“Think of the money, Alan,” Ziggy said as they worked. “Your mother promised that you wouldn’t have to put it into your college fund, right? You can spend it on anything you want.”

“If this is the kind of work we have to do for two weeks, I’ll be spending it all on deodorant,” Alan said, wishing that Josée was there shovelling too. She’d be agreeing with him and cracking jokes, not trying to make him like it.

The animal pen and its manure pile were next to a log cabin, part of an old-fashioned homestead—one of many on the property. Along with the houses, the pioneer village included an inn, a blacksmith shop, a general store, church, school and meeting hall, all filled with staff and volunteers in costume, doing the kind of things people used to do back in the 1800s. The log cabin (called the Fergusson House on the village map) was where Josée was working. There was an open firepit in the courtyard, with a big kettle of wax suspended over it. A woman used a ladle to fill tall, thin cans with the hot wax, which she brought over to the table where Josée and several visitors were standing. You took a piece of string and dipped it, over and over, into the wax, and slowly, it became a candle. It looked like Josée was enjoying herself, chatting with the tourists and laughing. As the boys looked over at her, she looked up and gave them a wave. Then she said something to a couple of kids who were part of the tourist group, and they headed over to the boys.

“This is where we’re supposed to pretend to be pioneers,” Ziggy said. “What do we say?”

Alan, who had acted in a couple of school plays, said, “Leave it to me.”

The kids, a boy and girl of about seven, approached and leaned over the fence that separated them.

“Aren’t you afraid of the animals?” the girl said. “Do they bite?”

Fred the donkey was standing a few feet away, munching a mouthful of grass and gazing off into the distance. The two goats, Gertie and Alice, were lying in the shade, still as shadows. It was hot, the sun was blazing down, and nobody was moving who didn’t have to.

“Nah, they’re totally tame,” Alan said. “Back in the old days, kids would ride the donkey to school, even.”

“Do you ride him?” the boy asked.

“I could, but we’ve got work to do here.”

“Isn’t that really gross, what you’re doing?”

“You get used to it,” Ziggy said. “People had to work a lot harder back then. They made you get up at, like, four a.m. and go and feed the chickens and milk the cows or goats or whatever, and then you had to walk ten kilometres to school in blizzards and sit in a freezing room with no internet.”

“Ew,” the girl said. “But you’d get to ride the donkey to school in the blizzard, right?”

“Not in the winter. Donkeys hibernate,” Alan said.

“They do not,” the boy said.

“This one does. He goes to a farm out in the country and sleeps in a barn all winter.”

“So, do you guys live here all the time? Do you sleep in that little house?”

“No, we live in town,” Alan said. “This is just a job, really.” Both boys began shovelling again, to show the watching children what real old-fashioned work was like. Alan was beginning to feel a bit like something in a zoo, and he was hoping the kids would get bored and wander off, maybe go make some more candles over there in the shade.

Alan plunged the shovel down into the muck, and there was a weird clang as he struck something hard. A horseshoe, maybe? Or a donkey-shoe? He used the tip of the shovel to scrape the dirty straw away, then gasped. Ziggy, looking down too, whispered, “Holy cow.”

Before the children could see what he had uncovered, Alan quickly booted a bit of straw over it.

“Hey kids,” he said, turning back to them. “We have to do some work, now, or we’ll get into trouble. You’d better go back to your parents.” Both children looked surprised and hurt for a moment, then the boy shrugged.

“When I grow up, I’m going to be a computer scientist,” he said. “I won’t have to get a dumb, stinky job like you have, anyway. C’mon, Lisa.” They turned their backs on the boys and returned to the candle-making area.

“That was smooth,” Ziggy said, but they were both too excited to care much. He flipped the covering straw back, and they both stared at what was there. Unmistakable, which was why Alan had covered it up so quickly. Lying under the dirty straw they’d been shovelling was a very big, very dangerous-looking, no-way-it-was-old-fashioned handgun.