Читать книгу Housing in the Margins - Hanna Hilbrandt - Страница 10

In the Margins: Allotment Dwelling in Berlin

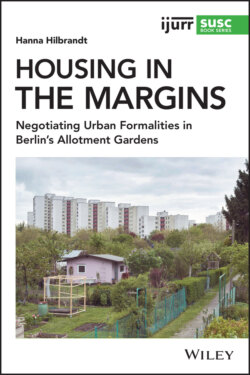

ОглавлениеAn abundance of research has documented the history of allotment gardens, but it has rarely associated these sites with informal housing. Most of Berlin’s allotment compounds (see Figure 1.1) go back to a period of industrialization and rapid expansion of the city at the turn of the twentieth century. They are frequently referred to as colonies – a term that I adopt and contextualize in Chapter 3. As that chapter also details in depth, Berlin has witnessed more than a century of allotment governance in which dwelling on one’s plot was variably forbidden and politically sustained. The dwelling practices that persisted throughout two wars, rival political systems, and the increasingly profit-driven use of urban land have left their vestiges in the contemporary city: today’s landscape of allotment colonies, 876 compounds with 71,071 garden plots on 2,915 hectares of urban space (SenUVK, 2019: 24), is served by an infrastructure of mini-scale allotment huts, electricity networks, water hook-ups, and telephone lines (Urban, 2013; Hilbrandt, 2015).

FIGURE 1.1 View of allotment colony in Berlin-Neukölln. Source: Michael Berger.

By and large, allotment gardens can be characterized as spaces of the lower middle class, though over-proportionally white. Most gardeners are of an older generation that has fostered social networks between allotment holders who have gardened, plot by plot, over decades (SenSW, 2019: 32). Despite repeated exceptions with far-reaching consequences for the acceptability of dwelling, permanent residence on these sites is generally prohibited – today most centrally through the Federal Allotment Law, the Bundeskleingartengesetz (BKleinG). Yet, allotment holders rely on a variety of regulations as they take up residence within allotment huts. To avoid any misunderstandings, it should be stated that allotment dwelling is not a mass phenomenon. In addition to 1,131 gardeners who hold dwelling permits (documentation of the Berlin Senate, provided in an interview, 18.09.2013), an unknown number of Berliners with other legal statuses permanently reside in colonies, particularly in those that have functioning infrastructures throughout the year, including electricity connections and water pumps. Schwarzwohnen [literally: “black” (here signifying clandestine and unlawful) dwelling] remains the exception,3 although my research has taught me to expect at least one or two permanent dwellers in each colony and higher numbers in some of the colonies at the periphery of the city. Conversely, Sommerwohnen [summer dwelling] is a rather frequent practice. It implies moving “out” into the colonies in early spring and returning “back” into the city in late autumn, and possibly subletting one’s flat during the stay on the plot, or inhabiting a hut throughout longer vacations, or routinely spending the night.

In the diversity of these practices, the case of allotment dwelling widens understandings of housing precarity in a European city. In contradistinction to studies of homelessness (Mitchell, 1995; Marquardt, 2013), camps (Clough Marinaro, 2017; Pasquetti and Picker, 2017; Picker, 2019), emergency shelter, or some of the work on informal settlements in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, allotment dwelling does not limit the study of housing precarity to an exploration of severe urban poverty. Berlin’s allotments – even if some may be inhabited – are commonly seen as orderly and tradition-bound. It is to a lesser extent that allotment gardens also provide refuge for the income-poor – people scraping by on unemployment benefits, or migrant laborers, or pensioners with limited means, for example. Yet the case of allotment dwelling also speaks to growing social divides in which those at the bottom of the income ladder are additionally disempowered through the tensions in European housing markets and their spatial and social effects.

Over the years in which I researched and wrote this book, investment-led policy, housing privatization, and the financialization of real estate have crucially changed Berlin’s housing conditions. In the aftermath of the 2007/2008 financial crisis, processes of displacement and the associated deepening of social divides have increasingly appeared to be the order of the day (Aalbers and Holm, 2008; Bernt, 2012; Soederberg, 2017). As a result, Berlin has experienced a resurgence of interest in the “new” housing question (Schönig et al., 2017; PROKLA, 2018). A plethora of urban scholarship (e.g. Holm, 2011; Uffer, 2014) has drawn into sharp relief that Berlin’s housing crisis has been politically caused through neoliberal approaches to housing provisioning and the resultant reductions of social housing and rent increases in all market segments; that it is structurally determined through the global financial crisis that moved Berlin’s housing stock into the spotlight of capital flows; and that the crisis has been aggravated through the population growth of the city (Investitionsbank Berlin, 2017).

As I argue in Chapter 4, literatures explaining the resulting processes of gentrification and displacement focus predominantly on the political interventions that allow for or hinder gentrification, or on areas that experience gentrification and displacement (Holm, 2010; Schipper, 2018). This includes qualitative attention to incoming middle- to high-income pioneers and gentrifiers or quantitative explorations of population mobility incidences and rent increases to identify affected areas (e.g. Döring and Ulbricht, 2016). Yet, the debate remains limited in providing an understanding of the affected populations, their housing trajectories, and new forms and locations of residency – in part due to the difficulties of locating displaced residents (although see Helbrecht, 2016). The scarcity of literature on displaced populations is indicative of the lacuna of qualitative studies on housing precarity – including on the many faces of housing practices in irregular conditions. To date, informal housing is hardly recognized as existing in Berlin or in other European, Canadian, or US cities and rarely researched in relation to processes of governance (but see Chapter 4 for a discussion of existing research). Thus, to develop a more complete understanding of housing exclusion, to grasp the practiced relations formal and informal housing have to one another, and to challenge the “intellectual segregation” between these extensive but still largely disparate debates, my discussion of allotment dwelling joins up three strands of work: a global literature on informal housing, the contemporary German housing debate, and more specific and partly historical accounts of urban allotments.

To be sure, my aim is not to establish a direct causal relation between the tightening of housing markets and informal housing practices in Berlin’s allotments. Rather, the book approaches questions of the housing crisis “sideways,” as Jackson (2015: 3) puts it, through examining one of the “back ends” of the housing crisis – temporary or permanent residency in sites not deemed appropriate for dwelling. This includes discussion of people’s lived realities, strategies of staying put, and interim solutions; for instance, when people lessen their rent burden by moving into their allotments over the summer and subletting their apartments during that time. In particular, Chapter 4 offers a rich empirical account of how and why gardeners take up residence within allotment huts. On the one hand, it illustrates the entanglement of formal and informal housing in the dwelling biographies of the allotment’s residents. On the other hand, it explores how residents experience their housing conditions in widely varying ways.

This perspective promises two conceptual contributions to understandings of housing precarity. First, allotment dwelling constitutes an object of inquiry through which questions of governance can be explored through processes of negotiation in which informality tends to be tolerated and sustained. Although I also discuss instances of evictions, allotment dwelling allows examining the normalcy of governance arrangements in which rule-breaking is mostly accommodated by all concerned. Instead of top-down regulation by a heavy-handed state, the case of allotment dwelling permits us to understand how such compromises are collectively secured. Second, and conversely, I maintain that a focus on understanding small-scale negotiation also fosters an understanding of registers of exclusion and boundary work that often remain uncovered in structural accounts of informality and the state. This includes discussion of how ethnic discrimination, self-regulation, and other boundary mechanisms undergird the compromises I previously discussed.