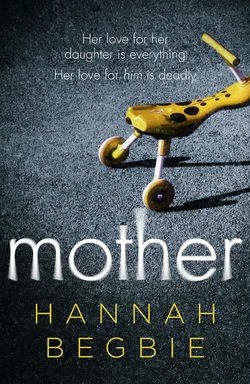

Читать книгу Mother: A gripping emotional story of love and obsession - Hannah Begbie - Страница 10

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеI bounced on the back of my heels and glanced down the canned goods aisle for any sign of my mother. We’d arranged to meet by the custard but then I was early, much earlier than I usually was to meet a mother who was always, without fail, on time.

We’d last spoken a few weeks ago, the morning after the parents’ meeting, when I’d telephoned to tell her about this thing that I’d met some people at and that I’d felt positive about. But I hadn’t got into the details of the thing before she asked me who had babysat that night. I hadn’t been prepared for the silence that followed when I told her it was Dave’s mum. I hadn’t been prepared for how bad I’d feel when the conversation ended without her knowing anything more about the thing.

In the end I’d been the one to break the silence by calling her after ten days and telling her that she was needed.

I pointed the trolley in the direction of the home products aisle and checked Mia was still comfortable and curled into my chest, still safe and snug in the soft hold and stretch of the sling. I held my ear close enough for it to be tickled by the soft fuzz on her head, which smelt of warm milk and clean new skin, and listened to the snuffling sounds she made before sleep. I set off at a slow pace, keen to deliver her into a heavy slumber so I could get a head start on buying the bleach.

Above me a luminescent sign waved on cold breezes – on it, a scrawl in thick black text, silently shouting:

Promotion. Buy One Get One Free.

Just buy the bloody tinned peaches.

Don’t say we don’t do anything for you.

And I wondered how Mum would be that afternoon.

You buy bleach like other people buy milk, she’d said to me the other week as she beheld five empty bottles of the stuff lying in the recycling box like a gang of defeated bowling pins. And she was right – we used it so much nowadays to keep an army of disease-causing bacteria in retreat: MRSA in the fruit bowl, E. coli in the toilet – but the way she’d said it had sounded like we were being hysterical.

I arrived at my aisle and began filling the trolley with soft bricks of antibacterial wipes. A long time ago, five years or more, Dave and I had taken a set of glorious supermarket shopping trips nestled within a set of equally glorious sunny days when we had filled most of a trolley with bleach and wipes and floor cleaner. Once upon a time those products had been used to clean and polish the big new house we’d found to fill and decorate with candle-holder, casserole pot wedding gifts. The same house in which we’d planned Dave’s new plumbing business, discussing his dreams of one admin assistant and fifteen plumbers by the second year, laying out the budget sheets on a family-sized kitchen table. The same big house that would accommodate our shared dream of two, three, perhaps four children.

Products to buff a shining dream!

Products to bury mortal threats!

Back then we’d wiped away the ghosts of the previous occupants – eradicating their food smells and the stains of their lives with nuclear yellow floor cleaner, bars of sugar soap and piles of scouring blocks. Then, in another glorious trip, we’d filled another trolley at the DIY shop – this time with sandpaper, paint samples (cerulean, slate and rose white) and plastic-sheathed brushes. Three children or four? we’d asked each other.

The sky’s the limit!

Then we waited in our new house. And those big spaces accumulated dust and spider legs, and the paintbrushes remained unopened.

And then I had thought: All right, maybe not four or even three children, as Dave employed his sixth plumber and thought about getting that office help.

We put down our paintbrushes and started having tests instead. Juggling the mood swings from hormone injections – too much! too little! – and the mood dips, and the terrible grinding disappointment of it all.

And, later still, when I’d lost count of the plumbers on Dave’s burgeoning books, we said: Maybe one would be enough. One child, and a spare room?

I’d travelled back and forth to the hospital on the number 8 bus. And in between appointments there was still the matter of getting to work on time and the dentist and the things people said, oh the things they said, the work appraisals and office politics, and the nausea and the bloating, the making time for ‘us’ and feeding ourselves.

Up until then, we’d always taken it in turns to cook, to surprise each other at dinner with the way Camembert didn’t work with chicken as expected, or how passionfruit worked better than expected with chocolate. And wine. Always too much wine! But then the tests and the waiting for results took up lots of energy. Something had to go. It’s not like we stopped having dinner. We still had dinner. Dinners at home, dinners out, aborted dinners, miscarried dinners. But they were increasingly silent and, I suppose less surprising because we knew by then that chicken did not work with Camembert. The point was that we were still sitting at that table together, the point was that in the middle of it all we hadn’t forgotten about us.

All the false starts. The recoveries. Starting all over again. No end.

Not for years.

‘Cooee!’ Mum called to me from the end of the aisle, waving a cauliflower in the air. ‘I’ve been here an age.’ She was inspecting the loose potatoes like an archaeologist with a new find when I arrived at her side. ‘Looked for you everywhere. We did say the custard and there you were, daydreaming by the floor mops, so I thought I’d make a head start on the fruit and veg essentials.’

She had once been tall, statuesque even. Now I spoke down to a silver-gold helmet of hair. ‘Thanks for coming shopping with me. It’s hard … with Mia. She’s fussy a lot of the time so having you here, it’s …’

‘Don’t be silly. It’s nice to be helping somehow.’ She made space in the trolley for the potatoes, nestling them between a bag of onions and a bag of apples. She had always been strategic like that. A knack for not bruising soft things.

Then she turned to me and laid her cold palms on my cheeks. ‘You’re always so proud. Like your bloody father, God rest his soul. It’s that Scottish DNA. You think you can do it on your own but there aren’t many who can do that and the sensible ones don’t even try. If your father had complained a bit more then maybe he’d still be here. Oh dear.’ She turned away from me to study a row of mangoes. ‘Look at these. Obviously hard as rocks!’

She knew I hated it when she talked about Dad’s death.

‘I’m not being proud,’ I said. ‘And I don’t want to do any of this on my own. The opposite, really, but the thing is that I’m finding people and what they say, well … quite hard. You know what Dad was like. He’d have found a way of laughing about it all, or at least he’d have something to say—’

‘I’ll tell you exactly what he’d be saying now.’ I flinched and a little boy looked over from the lemons towards Mum. ‘I’ll tell you exactly what he’d be saying now,’ she said more softly. ‘From that pedestal made of cloud and bloody sunshine you have him sitting on.’

‘I don’t—’

Mum snapped her handbag shut, having pulled out a carefully folded tissue. ‘He’d say there’s no use in dwelling. That it’s time to focus on the positive and the plans you can make. Work out what on earth you’re doing with your life.’ She found it easier to channel the things she wanted to say to me through my dead dad. ‘Dear oh dear, what on earth are the grapes doing under the satsumas?’

I rescued the grapes from under the satsumas. ‘I can’t think about what I do next. I struggle to plan for tomorrow. I don’t, I can’t think about next year or the future in general, I—’

‘You never could plan, and that’s why time ends up passing. It slips away from you. Always has.’

Mum had never been shy voicing her opinion of my IVF treatments, coming close to blaming my failure to get pregnant naturally on my general habit of tardiness. A failure of the uterus to make up its bloody mind.

‘I need to get my head around this situation. I’ve still got nine months of maternity leave left to decide what I do about my job and if I go back and—’

‘Last time you showed any ambition was when your dad was around and as he’s not here, I’m merely doing what he would have done. Encouraging you.’ She dabbed under her eyes with the tissue. Air conditioning always made them water. ‘But I’ve done a terrible job, haven’t I? Nothing’s moved on. You haven’t so much as researched new vocations. Office management clearly doesn’t suit you – your words, not mine. And so what about the inland revenue? I saw something in the supplements about them looking for heaps more tax inspectors.’

‘I hate numbers, Mum. They’re the main reason I don’t like my existing job.’

‘So useful to have a head for numbers in this world. Oh dear …’ She balled the tissue in her hand and looked around, eyes wide with panic: it was a moment before I realized it was because she couldn’t see an accessible bin. I took the tissue from her and crammed it into my own pocket.

‘It’s not up to you to have the answers,’ I said softly.

‘I feel terribly disappointed for you.’

One. Two. Three. Four. Five.

If you’re disappointed tell me it’s because your granddaughter will die before she has even lived, or that you lost your husband before his time, not because I don’t get on with office spreadsheet software.

Six. Seven. Eight.

Breath. Breath.

Then reply:

‘You don’t need to feel disappointed, Mum.’

‘And you look exhausted. Though this light is very unflattering. Come on, let’s get more fruit and veg into you.’ She piled courgettes into the crook of one arm and hooked a bunch of bananas with her free hand.

‘Thanks,’ I said. ‘But Dave doesn’t like bananas so we don’t buy them.’ She laid the bananas back with a sigh. ‘Although I saw some banana milk in his bag the other day, so that could have changed? We’re not getting the chance to catch up on that kind of thing … or anything much.’ Mum hadn’t interrupted me so I kept going. ‘I honestly don’t feel like talking about anything at the moment.’

She was rolling lychees between her palms like Chinese stress balls. ‘The weather doesn’t help. We all feel a bit low in the rain, particularly if the sun is supposed to be out. Now come on – if he doesn’t like bananas, then what? Peaches?’

I looked behind me. A mother was heaving her toddler-filled trolley toward us as if the summit of her mountain was still so far away. As she passed us she pulled a bag of something off a shelf and, tearing it open, crammed the contents into her child’s mouth. Bored and hungry, her toddler needed feeding and she needed silence.

‘Peaches are fine. Thanks.’

‘Well, I can’t reach them.’ She tipped her head in the direction of a green plastic basket on the top shelf. ‘Can you?’

I craned over the lychees and blueberries, holding Mia against me, and slid out a box of peaches I knew we’d never eat. ‘I’m cooking when I can, Mum. I even made a stew last week. I’ve got some left. You could come back and maybe we could have lunch? It would be nice to talk through some of Mia’s stuff. I … What’s wrong?’

Mum’s brow was furrowed and she scratched at her temple with nails she’d filed into soft-pointed triangles.

‘Oh dear,’ she said. I’d given her bad news, again. ‘If you’d come up with that plan before … but I’ve got a church meeting and it’s important that I go. Attendance hasn’t been good this last month. Any other time. Or maybe you’ll have dinner with me next week? Let’s say Wednesday. I’ll cook a chicken the way you like it, with all that artery-clogging butter. We’ll do that. Seven p.m. sharp.’

‘Dave’s mum and dad might be coming to stay that night.’

‘Oh. They’re babysitting again, I suppose?’

Mum was stockpiling green peppers into the bottom of the trolley, and wouldn’t meet my eye. I had no use for seven, eight, nine green peppers but I had even less use for an argument about whether they’d stay in the trolley.

‘They’re only coming for dinner, Mum, and if they stay the night they get to spend time with Mia first thing. It’s hard for them to see her otherwise. They both work in the week. It’s nice that I get to see you during the day. When you’re around.’

She tried a smile. ‘I suppose there’s an upside to my being too old to contribute to the economy. What marvellous people Dave’s parents are, fitting it all in.’

I stroked the length of Mia’s spine to calm the restlessness in her and in me. ‘The truth is that we don’t see many people at all at the moment. I just don’t feel like seeing—’

Mum came to an abrupt standstill opposite the yoghurts. ‘Look at me,’ she said. I looked down at Mia. ‘No, look at me, Cath.’ I looked at her. ‘Don’t think I’m not listening when you tell me repeatedly that you don’t want to see anyone. Are you getting out of bed in the morning? I don’t suppose you have a choice, what with the little one. Do you need pills again? At least we know which ones work. You must say something, you must ask. They did warn you, Cath. If you catch it once you can catch it again.’

‘Depression isn’t like getting a cold.’ My fingers worried at the folds of Mia’s sling, itching to pick up a pot of yoghurt and hurl it across the aisle as I screamed. Anything to shock her, to reboot her.

‘I wasn’t suggesting it’s a cold. But depression can be passed through the genes.’ She coughed into a balled fist. ‘I’m not at all sure whose side you’d have got it from. I did have an aunt who—’

‘I’m not depressed.’

‘I’m only trying to help.’

She took a deep breath and began buttoning her coat because the freezer section was always cold. I watched her as she did it, all the way to the topmost, strangle-tight button.

‘You’ve got a newborn baby,’ she said eventually. ‘And this rainy summer is very depressing for everyone.’

‘It’s not the weather.’

‘Even people who are normally very cheerful can end up feeling at odds. I heard a programme about it on the radio. In some countries they make children sit under light bulbs or none of them can get out of bed.’

‘That’s Vitamin D.’

‘No, I’m sure this was for depression.’

Mia squirmed angrily. I paced to keep her still, paced to walk off some of the blistering hot anger I felt at always having to soothe my mother every time she came into contact with something about me that she found difficult. As if I was a puzzle she found too frustrating to solve. Over and over. Time after time. I came to a halt at the end of the frozen aisle.

She’d followed me, a few steps behind. ‘What support are you getting?’ she said. I turned to see her, arms crossed tight across her chest. The cold was really coming off those freezer cabinets.

I looked at her closely and wondered when she’d decided to put fine lines of black back into her gold and silver hair, and when the skin had begun to sag off her bones like that. Like sheets draped off ladders. Because it was like seeing her again after an absence of years – as I thought, if Dad had been here, you wouldn’t have had to ask about what support I was getting because it would have come from him. You’d have known that and you’d have let him get on with it.

‘Well, let’s see,’ I said. ‘The thing I tried to call you about last week, the CF parents’ group? That was great actually. Everyone sat around and talked and we shared some of our experiences. I might try and do some fundraising, or something.’

‘Parents’ group? What, like AA?’

‘It’s run by one of the charities for cystic fibrosis. It’s a support group for parents of children with CF.’

‘I understand. Sharing the burden.’ She scanned a shelf of fish fingers. ‘If it’s sharing the burden you’re after, you’d be better off at the church.’

I clenched my fists and adjusted something on Mia that didn’t need adjusting. ‘Let’s not talk about me for a bit. How are you, Mum? Tell me how you are.’

‘Bearing up.’ She released a resigned and exhausted sigh. ‘Sarah Blackwell keeps on at me about Dad’s headstone. Tiresome cow. I won’t be pushed on it, particularly as all she wants is symmetry in the graveyard. All that landscaping. You’d do a better job of it than her. You’ve got a good eye for design. Perhaps you should consider that for your next career? Get your hands into the earth sometime?’

‘I can’t work with damp earth. With Mia, the bacteria – did you read the email Dave sent out with all the things that are dangerous for her? Like sandpits and lakes and soil?’

‘Yes, of course I remember, but you’re obviously feeling over-sensitive so I’ll keep my thoughts to myself. Oh look, coconuts on offer. In the frozen aisle, for no good reason.’ She picked one out of its wooden box and held it against the strip lighting. ‘I read that these give you a lot of energy. Something about the fats in them. You’ll be as right as rain after a few of these.’

I pressed a palm against the top of my head, but it was no good. The words began erupting before I could start counting to stop them. ‘Mum.’ I brushed a strand of hair from my face and straightened my back.

She lowered the coconut.

‘It’s not my diet, or the sleep I’m not getting, or the absence of a career plan. Coconuts aren’t going to relieve the burden. I’ve got feeding and nappy stuff to do, like everyone, but as well as that I’ve got nearly ten drugs a day to administer and a hundred threats to watch out for and hours of physiotherapy. And I don’t know if I’m doing any of it right. Too many digestive enzymes will hurt her. Not enough and she’ll get stomach cramps. I worry about walking under shop awnings when it rains in case dirty water drips off it and on to her. I cross the road when the street-cleaner vehicle is coming. Every single minute of the day I’m terrified I’ll get it wrong and it’ll be the start of her getting really ill. I’m so tired, Mum—’

‘Yes, all right. I understand.’ She flapped her hands like she was trying to disperse a cloud of tiny flies.

And I was crying again.

I’d spent a lot of time crying in the bathroom before we had IVF, and even more during IVF. Perched on the edge of the bath, overflowing with disappointment when another pregnancy test failed to produce a pale blue line. At the beginning, Dave was always there, his hand held over mine, our faces buried in each other like a couple of swans. But toward the end, after months and years had passed, he was there much less. And even if he was, I was never sure if he had heard me somewhere in the house and just decided not to come.

I wasn’t sure because I never asked and I never asked because I wasn’t sure if I wanted to hear the answer. But one day, after another negative test, I’d had enough. I had grown so tired of the prodding and the poking and the lacking and the not knowing that I walked into the kitchen and said to Dave: Let’s put the house on the market because, really, what’s the point of this place if it’s only going to be you and me? Have you ever thought that maybe this isn’t happening because we – you and me – don’t work? That maybe this isn’t supposed to work?

Despite all the tests, the doctors never found out what was wrong with us. There wasn’t a single sperm count or hormone level that was abnormal.

Dave left the kitchen after that outburst. It was a Saturday and the football was about to start but I think he missed the match that time.

We never spoke about what I’d said and then on the Monday he left for work with a smile, like our conversation was forgotten, like life had grown over any wound I had made. And, soon after that, an embryo grew anyway. There was life inside me and no space left for old memories of tears in bathrooms and kitchens.

Mum almost had her back to me now, like she was sheltering from the wind.

‘I don’t think you do understand,’ I said, crying. ‘No, of course you don’t. Why would you? You never ask.’ The last confrontation I’d had – with Richard – had felt exhilarating. But this had the contours of an old habit. Goading her. Pushing her for more than she knew how to give. ‘I’m tired because when I’m awake all I think about is how to keep her alive and when I lie down to sleep all I can think about is her dying anyway. I have dreams when I bury her and I wake up and nobody can tell me it’s only a bad dream.’

Come on, Mum. Tell me that you feel something. Anything.

Mum looked up and down the aisle. ‘Do calm down.’

She placed her basket carefully on the floor in front of her and bowed her head, as if she were taking Communion. When she looked up again her eyes were cold and determined. ‘Come to church. Next Sunday.’

I searched for a tissue in my pocket. ‘Mum, you’re not listening.’

‘There’s a noticeboard that people pin prayers on, prayers for people who are unwell or in need. If you come and look at that board you’ll see exactly how much illness and sickness is around us. You’re struggling, granted, but we are all tested at some point. Deborah Maccleswood posted a lovely little note about her daughter’s breast cancer. Such a difficult thing for that family to be going through, but they’re praying together and they’re supported by all of us in the church. You might find some solace in that.’

‘Why would I find solace in another family’s suffering?’ I pressed the tissue angrily to my cheeks. ‘And if there’s a God, a truly all-powerful God, then he or she or it is a fucked-up deity. Letting children suffer and die.’

Her face had lost all its colour. I didn’t care.

‘There’s nothing there,’ I said. ‘And if there was something up there? I’d spit in its face for allowing this.’

‘He gave us his only son,’ she said tearfully, angrily.

‘I wouldn’t give Mia’s life for anyone or anything. That’s what a mother should be, isn’t it? The person saying: No, stop, you’ll have my child over my dead body. But I’ll have to watch her be taken from me all the same.’

Mum turned to the cereals shelf and pulled a yellow-and-blue box off the display. ‘She’ll be eating porridge, soon.’ I could tell from the quiet of her voice that tears were near. She turned abruptly and walked back in the direction of fruit and veg, then halted – torn between her desire to be away from me and to have the last word.

‘You’re impossible. As bad as your father. I always say it.’ She swallowed. ‘I wish he was here too, you know.’ She turned her back again.

And just like that, the anger that had given me so much heat and speed was extinguished, leaving a leaden cold sadness in its place.

‘Mum. Please don’t go.’

And she didn’t. Instead she turned and walked towards me, her cheeks red and damp with tears. ‘Stop taking it out on me.’

‘I’m not.’ I wiped my tears away with cold fingers, my tissue now balled and crumpled up against Mum’s in my pocket.

‘You blame me. And you should. After all, I probably gave you the faulty gene. It won’t be your father. Nothing was ever his fault.’

‘It’s no one’s fault. It doesn’t matter who gave anyone what.’

She looked so sad and desperate then, lost like a child swallowed by a crowd. And so I went to her and hugged her as close as I could with Mia in the sling between us. ‘It’s OK, Mum, honestly it is.’

‘It doesn’t matter what you say. I know that Jesus loves you,’ she whispered to me. To Mia.