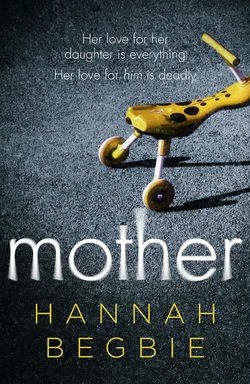

Читать книгу Mother: A gripping emotional story of love and obsession - Hannah Begbie - Страница 8

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеLate one afternoon, on a day that was hot and thick and had been promising a storm for too long, I boarded a red London bus. Three passengers on the top deck, dotted far from each other, heads bowed to their phones. Windows closed, greenhouse conditions. I pushed hard at my nearest window pane and was the only one to flinch when it opened with a bang, like something being fired.

I sat, felt the scratching nylon pile beneath my fingertips and resented the electric blue and fluorescent orange chosen to cheer the commuter. Don’t tell me how to feel with your upbeat seat fabric! I will make my own decisions about how I feel.

And I felt fine, actually. Probably better than in the three weeks and six days since diagnosis because now I was on my way to do something. I was on my way to meet people who shared my new language, to ask them: What is this island we have been exiled to? How long have you been waiting for the boats and how do we bring them here quicker?

Mum would be pleased because the kind of thing she might have said if it hadn’t sounded so harsh in the circumstances was, You’re a mother now! Take responsibility! Then I could say to her, But that’s exactly what I’m doing! Taking responsibility for my family. And my feelings.

Because the truth was that no one else – no husband, doctor, sister or friend – was actually doing anything to change the fundamental facts of it and so it was up to me. That was how I felt.

The bus sped through the paint-splatted, urine-stained, poster-torn mess of a city with its crammed stacks and storeys, its ripped holes and soldered joints. If it were up to me, I’d wipe the whole lot away with a bulldozer and start again.

Learn to clean up your own mess, Mum used to say when I was growing up.

I’m doing it, I’m doing it. Once I’ve finished, can I go out?

I was dealing with the mess. I was taking action.

The consultant with the blunt fringe had said: Delta F508 is the name of the mutated gene that you both carry. Mia has taken a copy from each of you.

Then I had said, She didn’t take them. We gave them to her.

She’d said something nice like we mustn’t blame ourselves. But who else was there?

I had plugged Mia into my own life source and helped her build her heart and lungs and organs using my blood and my oxygen and my energy.

I was her mother. I had given her life.

I was her mother. I had given her a death sentence.

Those were the fundamental facts of it.

I rested my head against the bus window, trying to stop my stomach from swimming and heaving, studying the tiny greased honeycomb prints of other people’s skin on the glass. I watched the sunlight thin under gathering clouds and reached for my belly, longing for the solid, reassuring curve of pregnancy and life – instead feeling fabric and loose, scooped-out flesh. Evidence of that life released into the world, my genie out of her bottle. And now I wished and wished and wished.

The panicky stuff had started small – the hours lost to finding my phone (in the fridge) and my keys (in the door). Those things might have been fine, the kind of thing a person does when they aren’t sleeping enough, but in the back of my mind I recognized the pattern in it all – the way my thoughts splintered and the tears came and any light in me felt dimmed by a choking smoke. But I couldn’t dwell too much on patterns and pasts because there was too much going on, what with the nappies and the feeds and trying to quell Mia’s tears and my tears and the anxieties of other people when they said to me How can we help? as I forced a smile and struggled to find an answer for them.

I got more frustrated and panicked as the words people spoke (mother, mother-in-law, sister, friends and other in-laws) rang hollow, fell flat, downright collapsed on the road to meet me.

Pavlova and lasagne? How lovely! It was kind of them, honestly it was, to think that they could change things with a meringue and a béchamel. They weren’t to know that, along with so much else, taste had been blunted in me.

The letters people wrote were sending me into a tailspin. The last time I’d even got a letter, in proper ink on paper, had been after Dad’s funeral. After someone had died, for God’s sake.

One of them started, ‘Of all the people for this to happen to …’ It made me think of a film I once saw, ‘Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world …’ People were amazed by the news. Privately relieved, some of them, I think … because statistics had to happen to someone. That’s the nature of the beast. My misfortune kept them safer. At least some good was coming of this.

But none of them did anything. None of them changed anything.

I wanted to throw up on the deck of that bus, like it was the only way I would rid myself of that grinding, persistent angst.

Fat drops of rain had started to fall and I was glad of it. I would be able to wash my face in them. Feel their chill on my skin.

As my stop approached I made my way to the top-deck stairs. The driver braked suddenly, before the lights and before the stop, and if I hadn’t been holding on so tight I would have fallen headfirst. A double tragedy, people would have said of our family. And then, when Mia was old enough, they would have said stupid things about chance and randomness and accidents – things they thought would reassure her. Leaving her equipped to deal with her mother’s death-by-bus-stairs.

A ridiculous balancing of deaths, one stupid but fast, the other lifelong, grinding and airless.

I had thought about running away, every single day since diagnosis. I had a credit card and phone – all that I needed to set up life elsewhere.

She loved you, they would tell her. She just couldn’t … some people simply don’t know how …

It must happen all the time: leaving it for someone else to deal with, telling yourself that someone else will be better equipped to meet the needs of the child. Believing it too, maybe.

Would you teach yourself to forget their face? Would that be the key to it?

My feet made hollow, violent hammering sounds as I ran down the stairs, unable to disembark quick enough into the rain, people on the lower deck looking alarmed and suspicious as I banged at the closed sliding doors with flat palms; Get me off this fucking bus! I couldn’t breathe. I was going to be sick.