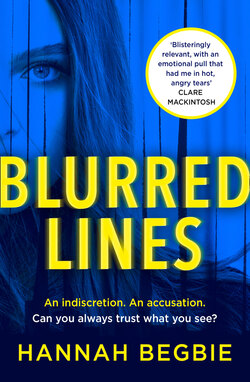

Читать книгу Blurred Lines - Hannah Begbie - Страница 9

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеHounslow, London

13 September 2003

Becky loves Saturdays. No school all day, and then another day just like it to collapse into after this one’s spent.

Today her parents have gone out to the garden centre and left her in peace to enjoy the high-pitched presenters of Saturday morning television as they leap about in front of butter-yellow and sugar-pink backdrops. When Becky is old enough to do this kind of thing, when it is her turn to interview people, it will be in her contract that she gets to choose the colour of the sofa – hot pink to offset her lime-green leggings, thank you! She will ideally graduate quickly from children’s television into a kind of late teatime, primetime Saturday slot just after the family game shows. And as a presenter she will have a habit of asking tough and yet elegantly emotional questions like, ‘But in the last analysis, how does that actually make you feel?’ Perhaps while reaching out a warm hand in genuine concern. It will sort of be her thing, so that after a while her guests expect it and people will talk about how she was the refreshing opposite of all the old men who do their chat shows.

Becky has a box full of diagrams of the set she will inhabit, drawing each one like a bedroom with four walls. It doesn’t occur to her that you need to put the cameras somewhere, so one wall has to be imaginary. She sees no trickery, no special effects. Just a bright, bubblegum reality that is kind enough to welcome her in, whenever she turns on the television.

Charred burgers and relish for lunch today, the classic Saturday meal in the Shawcross household, complete with Dad complaining about broken tongs and Mum saying he should bloody well do something about it then.

Becky goes to the local pool. In the changing room she watches other women’s bodies as they get in or out of their costumes. As she walks to the water, she is a catwalk model with all eyes on her. When she dives down, she is a dolphin or a jet-ski or a shark. When she returns home later that afternoon the house smells of hot dogs and frying onions: the conciliatory dish her mum offers her dad after a hard day’s arguing.

She calls out from the hallway. ‘It stinks in this house. Will someone please open the window? All my clothes are going to smell of gross oil and onions.’ Then she runs up the steps to her bedroom, two at a time, in a bid to rescue her party outfit.

Downstairs her mum begins a fresh diatribe on her favourite subject, which is ‘being blamed for bloody everything in this house’.

Becky stands at the mirror of her wardrobe in her underwear, wanting to look more sophisticated than she does in these baggy pink cotton knickers bought in bulk by her mum every Christmas. She needs to investigate alternative options. She hates the idea of a G-string, the notion that somehow you are a block of cheddar perpetually on the verge of being halved by a cheese wire. And then there’s the sheer hassle she’d get if she actually bought something nice (comfortable cut, bold-coloured lace) and her mother found them in the washing basket. The torrent of questions that would follow! Who was she thinking of impressing with a pair like that? Who the bloody hell did she think she was? Which boy exactly had she impressed so far? And the crowning glory: what precautions was she taking, and did she know that even condoms can’t prevent pubic lice from spreading?

Becky lays her outfit out on the bed and her make-up on her side table, so that everything is ready. She loves decorating herself: all that nipping and tucking and flaring and wedging, like taking a sharpened pencil and rubber to your outline and adjusting it accordingly.

She holds up a fluorescent-pink vest top with a spaghetti strap which, because it was bought at a flea market lacking a changing room, is too big and needs adjusting so the lace trim of her bra is not on display. She wreathes strings of beads and trails fake pearls about her neck until she is satisfied with how good the concentric circles look against a plain pink background. Then she takes her jeans – tight, low-slung, the fashion – and pours herself into them, ramming the zip closed twice before it stays put.

The next bit takes the longest. She outlines and flicks and smudges and colours in cheeks and eyes until she looks a picture: the best, most sophisticated version of herself, she thinks.

Just before she leaves, she stands a few feet away from the threshold of the kitchen rubbing moisturizer into arms that are dry and chlorinated from the pool, watching as her mum lays out a fresh cloth on the table.

Her dad turns to her and laughs, then says, ‘You look like you’ve fallen in the dressing-up box.’

Becky wants to say, Don’t be a dick, but she won’t risk being sent to her room and having her plans cancelled. Instead she settles for a sarcastic smile and a mumbled, ‘You’re not exactly setting Milan on fire with those Union Jack socks.’

They’re not the kind of parents who insist on collecting their child from a party at a set time. They don’t suggest it and Becky doesn’t ask them to. That’s one good thing about them. She’ll be home when she’s home.

Their party plans had nearly been abandoned because of Mary’s summer cold, which Becky would probably have been OK with, if she’s honest. But now that Mary is on the up, the only sign of her ailment a lower-than-usual voice, left gravelly by a week’s coughing, it’s all back on and they’re arm in arm, walking down the road from Mary’s house, with Mary pushing and pushing to see if Becky will do a pill with her tonight.

Mary is Irish and favours wearing pinafore dresses with band T-shirts rumpled up underneath. She is extremely persuasive. Her hair is terracotta red out of a packet which emphasizes the china white of her skin, which in turn emphasizes the rings of dark under her eyes which are there because she has to get up earlier than her body wants to, she says, which is one more crime that the education system has to answer for. Mary feels that the school week compounds the problem of weekends, which should ideally involve missing at least one whole night’s sleep.

‘So? Are you going to do one with me or not?’

Mary believes that, as friends, you go down together and you come up together. If it’s a good pill then you have a fellow traveller for the night, and if it’s a bad pill then you don’t die alone.

Today, Mary is disappointed about an unsupportive government and disappointed with the bags under her eyes, and Becky can’t quite bear to add to the tally, at least not yet, so she says: ‘Yeah, maybe I’ll take a pill. We’ll see. Yeah, go on then.’

Mary whoops because it is only a party when you are guaranteed to have fun and not die alone. Then she takes out two cigarettes, lights them both and hands Becky one as if smoking cigarettes together is the best way of sealing this deal of togetherness.

It is Saturday night and Becky is feeling good. Her skin feels lit with magpie-bright colours and sparkles, and it fits well. At this moment, walking arm in arm with her best friend, everything is as it should be.

Oh, to have a photograph of that moment, the time before the rest of it happened.

To have that to come back to, to tell yourself: you are still in there, that girl with flying hair and a newly lit cigarette and a whole weekend, a whole life, laid out for the taking. She is not lost to you. Imagine yourself back into that skin and feel the closeness of the fit. Persuade yourself.

But you are not watched by anything other than a fat, ginger housecat, which moments after you pass him forgets you for a rat-rustle in the bushes nearby.