Читать книгу Can We Save the Catholic Church? - Hans Kung - Страница 27

Christian Churches Need to Be More Christian

ОглавлениеCatholicism, as it evolved historically, and particularly modern Catholicism in its current form, cannot be the yardstick by which the Church measures itself. Many within the Vatican and many external ‘supporters of the Vatican’ want to commit the Catholic Church to a status quo which is both comfortable and profitable to them. And so they reject – always with reference to a ‘higher’ (i.e. papal) authority – any proposals for change in the pathogenic course they have adopted for the Church, and they rule out any serious reforms to the Church’s teachings and practice: if it is not Roman (i.e. does not toe the Vatican line), it is not Catholic.

But more and more Catholics are seeing through the knee-jerk reactions that have brought Rome more and more power and only worsened the Church’s pathological condition. No one who has even the slightest idea of the real history of the Church can either ignore its flaws, ruptures and cracks, deny the many contradictions and inconsistencies in its history, or gloss over and excuse them.

Conversely, however, the question arises: can such things really be reformed and transcended? I admit that I have become increasingly sceptical, not just in view of the current, lamentable situation in the Catholic Church, but also in view of the epic upheavals and paradigm changes that mark the history of all three Abrahamic religions, and particularly the history of Christianity, which I have analysed in two decades of laborious research. Neither Catholic leaders nor church historians have taken seriously the consequences of such shifts for our present-day Church.

I will return later to the topic of paradigm change, those epochal changes in the overall mindset and way of doing things that, in the history of the Church, have led to the formation of separate confessional traditions and churches. But here, I want to highlight at least briefly some of the problems facing the Church as a result of such changes.

Anyone who knows the Church’s history will ask themselves: can one seriously expect a Church so deeply rooted in a Medieval paradigm (‘P III’ in my terminology – see Editor’s Note) to embark on a new course in the future? Can one expect this of a Church which has largely forgotten the original Jewish–Christian paradigm of the Apostolic Church (‘P I’) and which only selectively accepts the early Christian–Hellenist paradigm of the first millennium (‘P II’)? Can one expect an adequate response to the current problems facing the Church from a Church that sees both the paradigm of the Protestant Reformation (‘P IV’) and the paradigm of Enlightenment and Modernity (‘P V’) only as a falling away from the true path of Christianity? How can such a Medieval, Counter-Reformation, anti-modernist Church manage the transition to a new, more peaceful, more just, ecumenical paradigm (‘P VI’) appropriate to the twenty-first century? Given the fact that, at the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church only partly managed to integrate the Reformation and modern paradigms and that currently a restoration of the pre-Vatican II paradigm is well under way, is such a Church at all capable of steering a path into the future that allows it both to preserve the original message of Christianity and express it anew?

And this brings us to the crucial point; the challenge to reform is addressed not only to the Catholic Church but to every church that considers itself Christian: the Protestant and the Orthodox churches are likewise not sanctuaries immune to similar criticism. The crucial question is always the same: Does one’s church faithfully incorporate and reflect the original Christian message, the Gospel, which to all intents and purposes is Jesus Christ himself, to whom each church appeals as its ultimate authority? Or is it mainly a church system with a Christian label, be it Early Christian/Orthodox, Medieval/Roman, Protestant/Reformed or Modernist/Enlightened?

Without a concrete and consequent return to the historical Jesus Christ, to his message, his behaviour and his fate (as I described it in my book On Being a Christian [1977]), a Christian church – whatever its name – will have neither true Christian identity nor relevance for modern human beings and society. For Catholics, that means that all the many Roman Catholic institutions, dogmas, doctrines, ceremonies and activities must be measured according to the criterion of whether they are ‘Christian’ in the strict sense of the word or, at the very least, not ‘anti-Christian’, in short, whether or not they are in agreement with the Gospel.

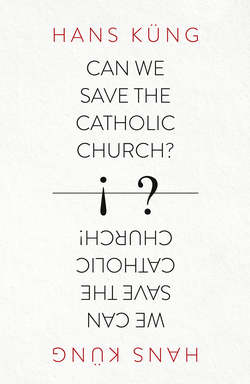

This is what so many people in the Church are hoping for when they say to themselves: our Church must become more Christian again, must once again model itself on the Gospel, on Jesus Christ himself. And to ensure that such hopes are not dismissed as an unrealistic theological agenda, I want to illustrate this point so crucial for the survival of the Church with an – admittedly drastic – image.