Читать книгу Lenin: A biography - Harold Shukman - Страница 10

1 Distant Sources

ОглавлениеVladimir Ilyich Lenin did not appear fully fledged on the scene as the leader of the radical wing of Russian social democracy. At the end of the nineteenth century, when he was not quite thirty, he was merely one among many. Julius Martov, who collaborated closely with him in St Petersburg and Western Europe between 1895 and 1903, recalled that Lenin cut a rather different figure then from the one he was to present later on. There was less self-confidence, nor did he show the scorn and contempt which, in Martov’s view, would shape his particular kind of political leadership. But Martov also added significantly: ‘I never saw in him any sign of personal vanity.’1

Lenin himself was not responsible for the absurdly inflated cult that grew up around his name throughout the Soviet period, although he was not entirely blameless. When in August 1918, for instance, it was decided to erect a monument at the spot in Moscow where an attempt had recently been made on his life, he did not protest, and only a year after the Bolshevik seizure of power he was posing for sculptors. In 1922 monuments were raised to him in his home province of Simbirsk, in Zhitomir and Yaroslavl. He regarded all this as normal: in place of monuments to the tsars, let there be statues of the leaders of the revolution. His purpose was rather to affirm the Bolshevik idea than to glorify personalities. Everyone had to don ideological garb, the uniform of dehumanized personality, and Lenin and Leninism were the main components of the costume. The deification of the cult figure was the work of the system which he had created and by which he was more needed dead than alive.

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov began to use the alias and pseudonym ‘Lenin’, probably derived from the River Lena in Siberia, at an early stage. His very first writings, in 1893, appeared, unsigned, in mimeographed form. He first used a signature, ‘V.U.’, at the end of 1893, and then a year later he signed himself ‘K. Tulin’, a name derived from the town of Tula. In 1898 he used the pseudonym ‘Vl. Ilyin’ when reviewing a book on the world market by Parvus (Alexander Helphand), translated from German. In August 1900, in a private letter, he signed himself ‘Petrov’, a name he continued to use in correspondence with other Social Democrats until January 1901, when he signed a letter to Plekhanov with the alias ‘Lenin’. He seems not to have settled into this alias straight away, and still went on using ‘Petrov’ and ‘V.U.’, as well as his proper name, for some time. He also adopted the name ‘Frei’ for part of 1901, and in 1902 ‘Jacob Richter’ vied for a while with ‘Lenin’. But from June of that year, it appears he became comfortable at last with the name by which the world would one day come to know him.

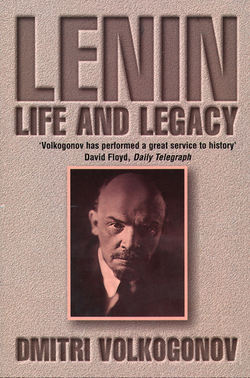

It is difficult to imagine Lenin as young. We are familiar with the photograph of the chubby little boy and high school student with intelligent eyes, yet he seems to have stepped straight from his youth into mature adulthood. Alexander Potresov, another early collaborator, who knew him well at the age of twenty-five, recalled that ‘he was only young according to his identity papers. You would have said he couldn’t be less than forty or thirty-five. The faded skin, complete baldness, apart from a few hairs on his temples, the red beard, the sly, slightly shifty way he would watch you, the older man’s hoarse voice … It wasn’t surprising that he was known in the St Petersburg Union of Struggle as “the old man”.’2

It is worth noting that both Lenin and his father lost their considerable mental powers much earlier than might be thought normal. I am not suggesting a necessary connection, but it is true that both men died of brain disease, his father from a brain haemorrhage at the age of fifty-four, and Lenin from cerebral sclerosis at fifty-three. Lenin always looked much older than his years. His brain was in constant high gear, and he was usually having a ‘row’ with someone, ‘row’ being one of his favourite words. It may not be a sign of his genius, but the fact is that, even when he was relatively young, Lenin always looks like a tired old man. Be that as it may, let us look at his origins, his antecedents and his background.