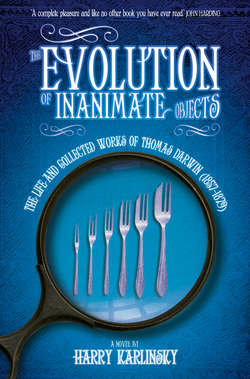

Читать книгу The Evolution of Inanimate Objects: The Life and Collected Works of Thomas Darwin - Harry Karlinsky - Страница 10

ONE DOWN HOUSE

ОглавлениеThomas Darwin was born on December 10th, 1857, the eleventh and last child of Charles Robert Darwin and his wife Emma (née Wedgwood). All but three of the Darwin children reached the age of majority. Mary Eleanor, third born, died in infancy in 1842 while the much-loved Annie succumbed in her tenth year in 1851. Charles Waring, born developmentally disabled one year earlier than Thomas, died at only two years of age in 1858. Of Thomas’s seven surviving siblings (William Erasmus, Henrietta Emma, George Howard, Elizabeth, Francis, Leonard, and Horace), Horace was the closest in age to Thomas, but almost seven years his senior. As a result of his much younger age, Thomas grew up in relative isolation from his older brothers and sisters, particularly during his adolescent years.

Home was Down House, a large residence sixteen miles south of London, England, located on the outskirts of the small village of Down (now spelled Downe) in the county of Kent. Charles and Emma Darwin moved to this quiet countryside some three years after their marriage, having found the social commitments of London society poorly suited to Charles’s health. After settling in Down House in 1841, and with the considerable aid of a large domestic staff, they resided there with contentment throughout their forty years of married life.

Figure 1. Down House:

Back of House from Garden with Trellises and Climbers, Summer Half of Year. CUL location-MS. DAR.219: 12.172-173. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Oddly, the earliest accounts concerning Thomas’s infancy and toddler years are found within the scientific literature. Charles Darwin was a loving and attentive father, but a child’s arrival was also an opportunity for the close scrutiny of a domesticated species of interest. Charles studied Thomas intensely, as he had his other children, and the initial observations of his youngest son were recorded in a vellum-bound diary, still extant as Appendix IV of the Oxbridge Unabridged Correspondence of Charles Darwin.

The notes begin with a meticulous account of Thomas’s reflex actions. Thomas first yawned on the third day of his life. On day thirteen, he sneezed. Between three and four weeks of age, he began to startle at loud noises. As Thomas slowly matured, his father’s brief comments evolved into more complex observations. By carefully monitoring Thomas’s facial expressions and the circumstances in which they occurred, Charles effectively recorded Thomas’s earliest experiences of anger, fear, affection, pleasure, shyness, and even his sense of morality.

It was at four months of age that Thomas first expressed fear. Until then, Charles had delighted Thomas by playing peek-a-boo while galloping on an oversized rocking horse, a family heirloom. On the evening of April 10th, 1858, however, Charles and the horse unexpectedly toppled quite violently. Thomas’s moment of surprise quickly transformed into stupefied amazement and then fear. Charles, lying prostrate and injured, still managed to note that, as Thomas watched, powerless, from his crib, his son’s eyebrows were raised and both his eyes and mouth were widely opened. In recounting the melodrama, Charles acknowledged he had reflexively scanned the rocking horse for signs of terror, searching specifically for dilated nostrils. Subsequently, Thomas would whimper whenever his father tried to reinitiate the game and the rocking horse was soon removed from the nursery.

Thomas’s calm demeanour was rarely broken and Charles recorded only one ill-tempered outburst. At seven months of age, Thomas glared fiercely when his nurse inadvertently dropped the bottle from which he was feeding. Gums clenched, Thomas briefly raised his hands as if to strike the offending nurse, but quickly reverted to passivity. The first indication of Thomas’s sense of injustice and morality soon followed. At eight months of age, Thomas refused to kiss an older sister, possibly Henrietta, when she declined to share her last piece of liquorice.

A notable feature of the entire diary (which ended when Thomas was eighteen months of age) is the frequent comparisons found within its entries. On the more pedestrian level, the timings of Thomas’s developmental milestones were consistently cross-referenced to those of his brothers and sisters. In general, Thomas’s progression was roughly equivalent to that of his siblings. Thomas did, however, show a much earlier aptitude for drawing, a fine motor skill he acquired when only fifteen months of age.

The far more interesting correlations were Charles Darwin’s whimsical comparisons of Thomas’s development to a diverse range of plants and animals. Insectivorous plants were more excitable, iguanas more agile, and rhododendron seeds much hardier. The most unusual inference was when Thomas’s melodious intonation of “Oh, Oh!” was deemed analogous to the musical utterances of the short-beaked tumbler pigeon.

Throughout Thomas’s infancy, Charles also subjected his youngest son to an ongoing series of experiments that were conducted with the assistance of the other Darwin children. To test Thomas’s startle response, Charles recruited Francis to play his bassoon from variable distances and directions. To test Thomas’s reflex withdrawal, Elizabeth was instructed to stimulate specific areas of Thomas’s limbs and torso with strips of blotting paper. Thomas tolerated the attention with good humour.

Always inquisitive, Charles’s conjectures and theories eventually became too much for Emma. Shortly after Thomas had begun breastfeeding, Charles noted that Thomas would protrude his lips whenever Emma’s bosom approached within five to six inches. After excluding any correlation with vision or touch, Charles generated a list of alternative explanations that included a possible association to the position in which Thomas was cradled when about to be fed. Although Thomas seemed unfazed, Emma could not bear the delay in feeding occasioned by Charles’s constant requests for Emma to withdraw her breast, reposition Thomas in her arms, and to again thrust her by then oozing breast towards Thomas. An exasperated Emma requested Charles to refrain from attending further breastfeeding sessions, a maternal injunction he amenably recorded and obeyed.

Though not intended as such, Charles’s notes concerning Thomas amount to an engaging biographical sketch of an infant, publishable immediately as an independent manuscript had Charles wished to do so. Instead, he characteristically delayed publication and chose to include selected observations of Thomas in a much later work titled The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, printed in 1872. Here, Charles’s meticulous surveillance of Thomas and the other Darwin children aided his delineation of thirty-four distinct emotional states in man. A careful reading of Expression of the Emotions reveals that depictions made under the headings of “Meditation,” “Self-Attention,” and “Shyness” pertained to Thomas. Though circumscribed in nature, Thomas’s three appearances within Expression of the Emotions convey a thoughtful and sensitive child.

Figure 2. Photographs Used to Depict Suffering and Weeping. In Darwin, C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray, 1872.

Plate 1 with six vignettes of babies. CUL location S382.d.87.1. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The evocation of “Shyness” is particularly poignant. After a week’s absence to obtain treatment at Dr. Lane’s hydropathic establishment,3 Charles was touched by Thomas’s response on his return home. Just seventeen months of age, Thomas initially averted his eyes and attempted to hide his face in his mother’s dress as Charles warmly greeted Emma and his other children. After hesitating briefly, Thomas then reached out to hug his elated father.

Other early glimpses of Thomas can be found within his mother’s correspondence. When younger, Emma frequently exchanged letters with many of her Darwin and Wedgwood relatives, particularly her Aunt Fanny Allen. At first, Emma enjoyed describing the activities of her children, especially William, Annie, and Henrietta. By the time Thomas was born, however, Emma’s writing had begun to take on a reserved and less personal quality. Emma’s earliest mention of Thomas occurred in association with his first birthday.

Down, Friday Dec 10th [1858]

My dearest Aunt Fanny,

It was so pleasant to receive your affectionate letter on this special date. Our dear Thomas is one year old today. His brothers and sisters adore him; he is so delicate and quiet. Yet still I am tired and drained. How thankful I will be when the children no longer require such constant care and attention. Even then I suppose Charles will never want to be alone. My poor Charles. His stomach aches again and he has been very uncomfortable.

Yours, E. D.

The letter would prove typical of much of Emma’s subsequent correspondence in which Thomas’s brief appearances were quickly eclipsed by details of Emma’s fatigue or the ill health of Charles or another child. At other times, Emma failed to mention any of her children altogether and instead addressed such details as household accounts, recent visitors, or the latest novel she had read. One exception was a letter Emma wrote many years later to her granddaughter Gwen (née Darwin) Raverat.4 After thanking Gwen for a recent visit, Emma discloses that Gwen’s stay evoked memories of her own children when they were young and the unusual games they would play. She then recounts in detail one amusement that was invented by Henrietta. It required hunting the stinkhorn toadstool exclusively by scent. Emma describes a young blindfolded Thomas as exceptionally adept at sniffing his way around the unmown meadow behind Down House until, “with a sudden leap,” he fell upon his “pungent” prey. The only other mention of Thomas within the letter is a brief reference to his death: “Tragically, your Uncle Thomas died of tuberculosis while travelling in Canada at age twenty-one.”

In confiding in Gwen Raverat, Emma may have been responding to her granddaughter’s interest in hearing such family anecdotes. Although Gwen never met her Uncle Thomas (she was born in 1885), she later wrote Period Piece: A Cambridge Childhood, an extended family memoir that places Thomas’s childhood (and health) in a helpful context. According to Gwen, all but one of Thomas’s siblings suffered from nervous difficulties. Elizabeth was “very stout and nervous,” Henrietta had “been an invalid all her life” and was portrayed as having an insane fear of germs; Francis seemed to have “no spring of hope in him,” Leonard “inherited the family hypochondria in a mild degree,” Horace “always retained traces of the invalid’s outlook,” while Gwen’s father, George, had “nerves always as taut as fiddle strings.”

Henrietta was the most disturbed: “When there were colds about she often wore a kind of gas-mask of her own invention. It was an ordinary wire kitchen-strainer, stuffed with antiseptic cotton-wool, and tied on like a snout, with elastic over her ears. In this she would receive her visitors and discuss politics in a hollow voice out of her eucalyptus-scented seclusion, oblivious of the fact that they might be struggling with fits of laughter.”

In accounting for his children’s astonishingly poor health, Charles Darwin blamed himself. He was certain they had inherited what he viewed as his constitutional weakness: various and often ill-defined symptoms that began shortly after his travels aboard the Beagle as a young man. Charles’s most consistent and distressing complaint was gastric discomfort associated with retching, chiefly at night. If severe, his stomach pains were accompanied by alarming, hysterical fits of crying. Charles also experienced uncomfortable cardiac palpitations as well as eczematous skin eruptions. At times he was incapacitated, enduring at least three episodes of prolonged sickness.

Charles’s diverse ailments were a constant worry to his family and he, in turn, fretted incessantly over the health of his children. He became particularly anxious following the death of his son Charles Waring, who had been born one year prior to Thomas and died June 28th, 1858, during a scarlet fever epidemic. Deeply affected by the loss, Charles became panic-stricken that Thomas would also fall ill. For the remainder of that year, an exhausted Charles monitored Thomas’s breathing during the night. When finally challenged by Emma, Charles cited the nocturnal habits of the Indian Telegraph plant, explaining that circadian rhythms could significantly stress breathing patterns. Emma was unconvinced and forbade Charles from further disturbing both his and Thomas’s sleep.

Despite his ill health, Charles Darwin maintained a relentless and rigid work schedule. Each day, as a rule, he was in his study, quietly reading, writing, and attending to correspondence, or carefully dissecting the latest specimen to arrive by post. While Charles professed to require absolute solitude while working and wished to be interrupted only in urgent circumstances, he in fact welcomed his children’s playful intrusions. Thomas would peek in and, with his father’s assent, tiptoe quietly across the study to read silently by the fireplace. Charles would often take such opportune moments to instruct Thomas on the use of various scientific instruments. At age eight, Thomas was reported by Emma to have looked up from his father’s dissecting microscope and said, “Do you think, Papa, that I shall be this happy all my future life?”

Throughout his childhood, Thomas also joined his father on the Sandwalk, a “thinking path” Charles had built behind Down House. Thomas and Charles enjoyed the constitutionals they shared round its circuitous course, which was named for the sand used to dress its surface. One summer, Charles grew curious about the bees that disturbed their otherwise contemplative walks. In the guise of a game, he recruited Thomas and his brothers to track the bees’ movements. After dispersing his sons around the Sandwalk, Charles instructed each to yell out “Bee!” as one flew by. Charles would reposition his assistants in accordance with these cries and, in time, the bees’ regular lines of flight were determined. Thomas was adroit at sightings and would fearlessly tear after the bees as they flew by. An agitated Charles, fearing Thomas might be stung, would quickly redirect his youngest son back to his original post.

Even with Charles’s persistent anxiety over Thomas’s health, the two enjoyed an affectionate relationship. It was Emma, however, who attended more directly to Thomas’s day-to-day needs. She was forty-nine when Thomas was born (Charles was forty-eight). Undeterred by the risks associated with pregnancy at her advanced age, and often restricted to bed rest due to her pronounced morning sickness and fatigue, Emma tolerated her confinement with Thomas without complaint. Thomas’s earlier than anticipated birth was precipitous. Finding his wife suddenly in labour, and with Henrietta and Elizabeth at his side, an apprehensive Charles had administered chloroform as they waited for the local doctor to arrive. An over-sedated Emma was virtually unconscious when Thomas was delivered.

In between doting on Charles, raising her other children, and supervising a large household staff, Emma cared for Thomas in her characteristically pragmatic fashion. Resurrecting storybooks she had written years before as a young Sunday school teacher, Emma also served as Thomas’s first tutor. It was from such simple Bible stories that Thomas was taught both reading and religion — what Charles fondly referred to as his wife’s abridged version of the three Rs. Thomas’s religious instruction was of central importance to Emma. Even as a toddler, it was compulsory that a scrubbed and well-dressed Thomas walk with Emma, and all those siblings then at home, to the local church. After services, Emma would exchange pleasantries with the other families in the small adjoining churchyard. Although Emma encouraged Thomas to play with the other children, he preferred to linger at her side, “Alone, but not lonely,” according to Emma.

Thomas also participated from an early age in his mother’s charitable affairs. Revered by the parish community, Emma quietly supported those who were ill or in financial need. Each week, with Thomas as her “assistant,” she prepared homemade remedies that were then dispensed to grateful congregants, often with an accompanying food basket. Many of her medicinal recipes were based on prescriptions first written by Thomas’s physician grandfather, Dr. Robert Waring Darwin. Although all her generous parcels were appreciated, a particular favourite with the parishioners was Emma’s potent gin cordial laced with opium.

Thomas proved helpful in the kitchen, at first retrieving the various ingredients from the “physic cupboard” that Emma would carefully weigh and measure. As he grew older, he took direction from both Emma and Mrs. Evans, the family cook who served the Darwins for many years. One of Thomas’s early chores was to assist Mrs. Evans in the scullery, a small room beside the kitchen where the dishes and kitchen utensils were scrubbed. Despite difficulty in reaching the top-most drawers, Thomas’s responsibilities soon included returning the cleaned cutlery and serving pieces to the large antique sideboard that ran the length of the Darwin dining room.

In addition to their impressive Wedgwood dinner service,5 the Darwins also owned a large and eclectic assortment of serving utensils, as Emma often entertained her extended family. A number of these implements, such as marrow forks and cream ladles, were curious in appearance and Mrs. Evans would challenge Thomas to identify their purpose as the two worked together. Though only four years old, Thomas immediately recognized that a u-shaped, narrow-bladed set of tongs was used to serve asparagus. Not even his father had initially appreciated their function. Many years before, the piece had been mailed to Charles as a wedding gift from his friend J. M. Herbert. In the accompanying letter, Herbert, in an effort to be amusing, only drolly stated the enclosed gift was a representative of the genus Forficula (a reference to the common earwig, an insect that the silver utensil apparently resembled). To reward Thomas’s unexpected acumen, Mrs. Evans insisted thereafter on serving him the first portion of roasted asparagus whenever she prepared the seasonal vegetable. Though Thomas disliked asparagus and would have far preferred priority for Mrs. Evans’s gingerbread, he graciously accepted the asparagus as the gift he knew it to be.

On turning five, Thomas began to receive sporadic tutoring from Mr. Brodie Innes, vicar of Down. Mr. Innes focussed on expanding Thomas’s reading and writing skills, and also introduced Thomas to basic arithmetic. Though Thomas learned to add and subtract, Mr. Innes had little talent for teaching. Recognizing his own limitations, he encouraged Emma to allow Thomas to join his sisters Henrietta (while she was still at home) and Elizabeth in the small schoolroom at Down House, where a series of daily governesses supervised the girls’ home schooling. As Emma Darwin held strongly that the “Devil finds work for idle hands,” the emphasis of the girls’ education was skewed towards embroidery and handicrafts. As one activity, Thomas made a number of flimsy Easter baskets. He had intended to present individual members of his family with an identical holiday gift but each basket was significantly and disappointingly distinct from its predecessor. Thomas would later conclude that such imperfect production was an important source of diversity in the world of artefacts.

Thomas also attended his sisters’ weekly Wednesday Drawing Class in the local village. Miss Mary Matheson, the teacher, was a diffident but well-intentioned spinster whose style of instruction was to emphasize accuracy over artistic interpretation. Although never hesitant to erase errant lines, she was genuinely supportive, and Thomas was a conscientious pupil. While Thomas was self-deprecating about his ability to draw, these early lessons came to useful advantage. He later produced his own illustrations for the manuscripts he authored.

If the weather was remotely tolerable, Thomas was excused from all lessons and allowed to play outside. Emma and Charles were permissive parents, and their sole stipulation was that Thomas remain in earshot of the one o’clock bell for lunch, the family’s principal meal of the day. Thomas would spend hours digging in the sandy soil of the kitchen garden and the orchard, deploying toy soldiers on the ample lawn, and inspecting the considerable number of birds’ nests in the trees that bordered the Sandwalk. A favourite sanctuary was a small abandoned summer house, just beyond the Sandwalk, where Thomas enjoyed drawing in chalk on its decaying wooden walls.

The only drawback to such activities was their solitary nature. For most of Thomas’s childhood, his brothers were either at boarding school or living away from home. On occasion, Parslow, the Darwins’ long-serving butler, would challenge Thomas to a game of quoits. Akin to horseshoes, this entailed tossing rings towards a spike in the ground some distance away. To Parslow’s irritation, Thomas’s throws were rarely accurate and he was prone to closing his eyes and simply hurling the rings as far as he could. This resulted in long, and at times fruitless, searches for the hard-to-find rings.

When available, Thomas’s favourite outdoor play-fellow was his father, but Charles seldom had the energy to engage in child-driven games. For more consistent fellowship, Thomas relied on the cows, pigs, and ducks that also resided on the eighteen acres upon which Down House stood. During Charles’s “pigeon phase,” Thomas spent considerable time in his father’s pigeon house, where he quickly learned to mimic a number of pigeon sounds, including their warning call of distress: coo roo-c’too-coo. Thereafter, and with the amused collusion of his father, Thomas would loudly sound coo roo-c’too-coo each time a member of the clergy called upon the Darwins. A forewarned Charles could then hurriedly retreat to his bedroom with an apparent exacerbation of any number of physical symptoms, much to Emma’s annoyance.

Thomas was also inclined to flee to his bedroom to avoid company and was generally perceived as shy. His smallish room was located on the second floor, one of the many bedrooms in Down House’s large three-storey structure, which had been altered and expanded over the years to accommodate the growing numbers of Darwins and domestic staff. One means to entice Thomas downstairs was the sound of a billiards game. Just prior to Thomas’s birth, a billiards table had been installed in the old dining room, and the game immediately became a favourite form of recreation for the entire household. It was Thomas’s task to methodically organize the balls at the beginning of each family tournament using a triangular rack that had been crafted expertly out of cork by Jackson, the Darwins’ groom.6 Charles often won, likely because Emma had instructed her sons “never to beat Papa.”

Thomas would also leave the security of his room on the sound of a secret knock. Thomas’s bedroom was directly beside larger quarters shared by Henrietta and Elizabeth. On hearing three taps in rapid succession, Thomas would dutifully open his door and descend partway down the staircase as his sisters furtively dressed in their mother’s jewels and wardrobe. The former were kept in a simple locked wooden box that first had to be quietly removed from their mother’s room. As the key fitted badly, Henrietta and Emma often resorted to violently shaking and bashing the box before it would open. Again, Thomas’s skills as a pigeon were required as he timed loud calls of coo roo-c’too-coo to mask the sounds arising from his sisters’ inept thievery. These calls had the unintended consequence of also sending his well-trained father scurrying to his room only to emerge some time later, uncertain as to whether any of his physical symptoms were still required. Otherwise, when not involved in such clandestine activities, Thomas preferred to spend long hours in his comfortable but cluttered room, reading, drawing, and, most satisfying of all, organizing his various collections.

From a young age, Thomas was an entrenched collector. Though he amassed all sorts of objects, his greatest passion was for accumulating buttons. These were organized by size, shape, and colour, and were sorted into trays and jars that Thomas appropriated from his father’s dissecting supplies. As Thomas’s expertise increased, he also began to identify each button on the basis of its composition. This was challenging, as many button materials closely resembled each other. Thomas taught himself to insert a fine, heated needle in the back of each button in order to smell for a distinct odour, such as the stagnant saltwater smell associated with tortoise-shell. The technique was time-consuming, but it allowed Thomas to sort and re-sort his buttons according to finer distinctions and also garnered his father’s admiration for his methodical perseverance.

Although Thomas was free to retire to his room as he wished, he was generally expected to spend evenings with other members of his family. After a relatively late and simple tea, it was the Darwins’ custom to gather in their large unpretentious drawing-room. This was a time for discussion, affable loitering, and two rituals, the first of which was the collective reading aloud of novels.7 Thomas’s favourite story was The Ugly Duckling as read by Henrietta. His eldest sister was masterful at impersonating the ducks whose dialogue animated the fairy tale. At one point in the story, a mother duck instructs her ducklings to “now bow your necks, and say ‘quack.’” Taking his cue, Thomas would dutifully bend his neck and boisterously “quack” along with Henrietta, much to the pleasure of the Darwin household.

Charles’s enjoyment of Thomas’s participation was twofold. Aside from revelling in Thomas’s joie de vivre, the transformation of a homely and unwanted baby bird into a graceful and beautiful swan was for Charles, above all, a “eugenics” parable.8 Although a swan’s egg had accidentally rolled into a duck’s nest, the ultimate superiority of the “ugly duckling” over the other barnyard ducks was predetermined by its genetic lineage. Charles, who supported the concept of selective breeding, saw Thomas’s enthusiasm for The Ugly Ducking as a sign he was a fellow eugenicist, one who recognized the importance of nature over nurture.

After the shared pleasure of reading, it was then time for backgammon, the second of the evening rituals. The games played by Charles and Emma were undertaken seriously, with Charles uncharacteristically boasting on one occasion, “Now the tally with my wife in backgammon stands thus: she, poor creature, has won only 2490 games, whilst I have won, hurrah, hurrah, 2795 games!” Although the children were expected to remain neutral, Thomas and his siblings would openly cheer their mother’s victories.

Following backgammon, Emma, a competent pianist, might then entertain the family by playing a number of classical pieces. This was an opportunity for Thomas to do his schoolwork, to read, or to quietly withdraw to his room. By half past ten, it was bedtime for Thomas and the entire Darwin household.