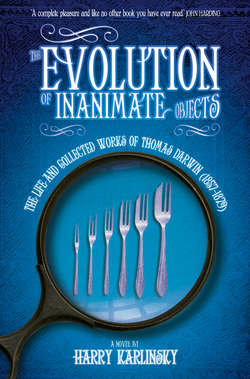

Читать книгу The Evolution of Inanimate Objects: The Life and Collected Works of Thomas Darwin - Harry Karlinsky - Страница 7

PREFACE

ОглавлениеThis work was intended to be a treatise on the history of Canadian asylums, particularly the London Asylum, which was among the first Canadian facilities established for the care of the insane. Opened in 1870 three miles east (at the time) of the city of London, Ontario, by 1879 more than 700 patients were lodged — a word chosen carefully — within its imposing structure. Regrettably, detailed descriptions of the initial patients and their illnesses are virtually nonexistent. Although casebooks, now housed in the Archives of the Province of Ontario, were maintained throughout each patient’s stay, the most consistent entries at the time of admission were limited to the patient’s name, sex, age, religion, birthplace, occupation, and civil condition (whether single, married, or widowed). Additional notes describing a patient’s symptoms or circumstances prior to admission were rare.

Sadly, “scant though this admitting information was, it was far more than was usually recorded later in the patient’s career.”1 Career was an apt word. The majority of those admitted to the London Asylum did not recover and receded quietly into the anonymity of institutional life. Most commonly, subsequent documentation was confined to brief annual notes to the effect that a patient’s clinical status had remained unchanged. Only dramatic and untoward events altered this singular and uniform rhythm.

My preliminary research included a casebook review of all admissions to the London Asylum during the year 1879. On July 2nd of that year, Thomas Darwin, age twenty-one, was assessed and admitted by Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke, Medical Superintendent. Aside from the dull identifying details referred to above, there were no further clinical observations. Mr. Darwin was a single male of unstated religion and occupation. His birthplace was Down, England. An accompanying, and apparently standard, document issued by the Department of the Provincial Secretary of Ontario authorized transfer of Mr. Darwin from the Toronto Gaol (now better known as the Don Jail), where he had evidently been imprisoned for the previous twelve days as “dangerous to others.” The only additional entry in Thomas Darwin’s casebook was dated just under four months later — “Death due to tuberculosis — October 23rd, 1879. R. M. Bucke.”

The surname Darwin aroused my immediate interest. There was Charles Darwin, of course — the Charles Darwin — of On the Origin of Species. But who was Thomas?

The imperfect story has now emerged.

Thomas Darwin was the last of eleven children born to Charles Robert Darwin and Emma Wedgwood. Scattered details of his early years can be found by focussed reading of obvious sources — primarily the preserved correspondence of Emma Darwin (particularly the letters to her maiden aunt, Fanny Allen) as well as the affectionate but unpolished accounts of Charles Darwin’s life by various descendants. The writings of Charles Darwin also contain a number of references to his youngest son. These include his Autobiography as well as his text The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals where descriptions of Thomas appear on three occasions. There are also the “scientific” observations of Thomas’s first eighteen months contained within one of his father’s unpublished diaries.

Little preserved material relates to Thomas’s adolescence or early adulthood. There are the brief annual reports of his student experience at Clapham, a boarding school attended by other members of his family. Accounts of Thomas’s subsequent two years at Cambridge University are largely confined to the transcriptions of his readings to the Plinian Society, a student group devoted to discourse on the natural sciences, as well as a preserved expense notebook with its list of purchases incurred during Thomas’s brief research excursion to Sheffield. There is also Thomas’s single letter to his father, and his father’s response, both previously published in various compilations of Darwin correspondence. Finally, brief reminiscences of Thomas appear in an acquaintance’s memoir.

According to Darwin family lore, an otherwise healthy Thomas tragically and abruptly died of tuberculosis while travelling in Canada following his second year at Cambridge. Essential to the expanded, and surprising, life story presented in this account are two key and previously unappreciated collections of primary sources.

First and foremost, my enquiry into the career of Thomas Darwin’s Canadian physician, Richard M. Bucke, led to an assortment of relevant materials now housed in the Rare Book Room at the University of Western Ontario. These include Bucke’s diaries, one of which contains a number of entries concerning Thomas’s psychiatric illness along with a letter, almost certainly confiscated, that Thomas wrote to his mother near the end of his confinement in the London Asylum. As well, there is the brief correspondence — previously unpublished — between Bucke and Charles Darwin, which includes a short note that Charles Darwin requested Bucke deliver to his son. The collection also includes Bucke’s extensive scientific and personal correspondence, including the first draft of a letter he wrote to the physician William Osler concerning Thomas; letters to and from J. W. Langmuir, the province of Ontario’s Inspector of Asylums, Prisons, and Public Charities; and of less relevance to this account, notes to and from the poet Walt Whitman. Lastly, two additional documents associated with Thomas’s transfer to the London Asylum that were amongst a series of “Admission Warrants and Histories” dating to the early 1870s were a significant find. This material was relocated to the Rare Book Room on the closure of a small archival and teaching museum that had previously been maintained in what is now London’s Regional Mental Health Care facility.

The second crucial array of source material revolves around Thomas Darwin’s unpublished manuscript submitted to the journal Nature. As Charles Darwin’s letter to Bucke alluded to this work, I contacted the current administration at Nature’s head office in London, England. The article in question (titled, “Hybrid Artefacts and Their Role in Our Understanding of the Evolution of Inanimate Objects”) as well as a copy of its letter of rejection was eventually unearthed in an archived file.2 In what must have been an extraordinary circumstance, Thomas’s submission prompted a concerned Joseph Norman Lockyer, the Editor of Nature at that time, to write to Charles Darwin. A copy of this letter, as well as Charles Darwin’s response, was also preserved in the Nature file.

In summary, what was intended to be a (lively!) academic account of Canadian asylums circuitously and with growing momentum has evolved into a biography of Thomas Darwin and a repository for those images, letters, and manuscripts that unfold his story. Chapters 1 to 4 provide a brief sketch of Thomas’s life — from his earliest days at Down House, through school days and Cambridge to, finally, his involuntary admission and subsequent death in the London Asylum. Thomas’s known scholarly works, all related in some way to his unusual interest in eating utensils, are reproduced in Chapters 5 to 8, along with details of their critical reception. Original source material related to his psychiatric illness and his confinement in the London Asylum is presented in Chapters 9 and 10.

The concluding Epilogue is a contemporary reappraisal of Thomas’s scholarly contributions as well as his underlying illness. Thomas Darwin’s life merits such resurrection, both as a testament to his significant accomplishments and for the bittersweet depth it adds to our knowledge of Charles Darwin, eminent scientist and devoted father.