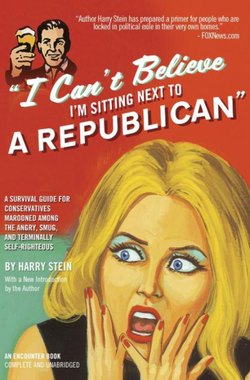

Читать книгу I Can't Believe I'm Sitting Next to a Republican - Harry Stein - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFriend or Faux?

WHAT ARE LIBERAL “FRIENDS” SAYING BEHIND OUR BACKS - AND, OKAY, WHAT ARE WE SAYING BEHIND THEIRS?

THIS IS GOING to get personal. Then, again, when the subject is sundered friendship, what else could it be?

I used to have a good friend - let’s call him Nick. A writer specializing in popular culture and politics, he was a lefty from way back - but, then, when we met, so was I. Though I was aware that he was somewhat baffled when I began my rightward drift, I was caught short - and royally pissed off - when a couple of friends in common reported he’d told them I’d changed only because I’d recently struck it rich with a book deal.

“Sure, I said it,” he replied immediately, unembarrassed, when I called to demand whether the report was accurate. “I think it’s true.”

“What the hell are you talking about? A, I’m not making all that much from the book. And B, money doesn’t have a damn thing to do with it!”

“Listen,” he said coolly, in that smug, high-handed way of his that somehow had never bothered me before, the one that I’d come to associate with so many on the Left, “as far as I’m concerned, greed is the only reason anyone ever becomes a right-winger.”

I guess there’s something to be said for that kind of honesty, but nothing I was interested in. The friendship ended right there.

There’s an aphorism attributed to Indira Gandhi that applies: “You can’t shake hands with a clenched fist.”

Talk to conservatives, especially those who started out on the Left, and you’ll hear a lot of stories like that. “It truly is astonishing how few liberals credit those on the other side with having any principles or ideals worthy of respect,” notes John Leo, the columnist, whose social circle includes many liberal eminences in journalism and the arts. “You can go your whole life and not hear a liberal take seriously any conservative argument - they just yell ‘racist’ or ‘fascist’ and think they’ve won.”

True enough, direct attacks on one’s very decency, like Nick’s on mine, are hardly the norm; civility is the natural order of things and most of us are especially protective of our friendships. But with a certain kind of adamant left-liberal, the possibility of such an outburst is always there, lurking, lurking, and there’s no telling what will set it off.

For Amy Anderson’s impassioned, irrational, newly left-of-center friend Jane, the tipping point was Fahrenheit 9/11. “One night I’m in the kitchen, trying to get dinner on the table for the kids,” recalls Amy, a good-natured, tart-tongued Westchester mother of two, “and the phone rings. She’s just seen this ridiculous movie, and it’s like the road to Damascus - she’s seen the light! She starts haranguing me: ‘How can you support these monstrous people? What is wrong with you?’ Just this emotional sturm und drang, viciously attacking me, hammering and hammering away. This, mind you, from a woman who does not read the paper, does not listen to radio, someone not plugged in in any way. I swear to God, she didn’t even know who Rupert Murdoch was! But we’d been close since college, she was my maid of honor and godmother of one of my children, and I wanted to save the friendship. So finally I said, ‘Jane, stop, we cannot talk about this.’ But, really, the damage had already been done.”

For Marlene Mieske, a psychiatric nurse and reformed Sixties veteran, it was the right to bear arms that abruptly ended a friendship. “We’d always gotten along wonderfully, this woman and I, and just then we were co-chairing a blood drive. But it was shortly after Columbine and we were in New York City, so someone walked in with an anti-guns petition. Of course, everyone but me immediately signed. When I refused, this woman was beyond furious. Her attitude toward me changed instantly - it was literally as if she couldn’t stand the sight of me, just stood up in a rage and started to leave. I said, ‘Hey, hold on, wait a minute. Let’s talk about this. You’ve got to understand that I grew up in the country, my father hunted, so to me it’s okay - it’s the Second Amendment, part of the Constitution.’ She wouldn’t even answer. And she never talked to me again.”

Nor, she adds, was such a thing unique in her experience.

“The people I work with are very caring, but they’re almost all liberals, and to them my beliefs are just incomprehensible. I’ll never forget having lunch in the conference room of the Brooklyn Bureau of Community Service, right after Giuliani announced he was withdrawing from the Senate race with prostate cancer, and all these people, my friends, are going ‘Yesss, Giuliani has prostate cancer! Isn’t that the best news you’ve ever heard?’ And I said: ‘Tell me, how would feel if it were just announced Hillary has breast cancer?’ They just looked at me blankly, and I said: ‘Enough said.’ From that time on, they never talked in front of me again. I was labeled - and it was my problem, not theirs.”

“Another woman,” she adds, “your typical major Upper West Side liberal, someone I’ve known for twenty-seven or twenty-eight years, actually said to me, ‘Marlene, I know you’ve worked with the mentally ill, so I know you care about people. But how can you be a good person and a conservative?’ It’s sad - we’ve now reached the point where we really can’t really discuss anything.”

On the basis of my random survey, stories of friendships fallen victim to ideology are told by men and women in roughly equal numbers, but they tend to differ considerably in tone. We men generally dismiss our ex-friends, as Norman Podhoretz memorably dubbed his own impressive roster, with bemusement or contempt, identifying them as the jerks they are. “Every time the name Palin came up, his wife would start frothing at the mouth, and he’d follow right along” as one guy says of a recently jettisoned pal. “Why would I even want to stay friends with a wimp like that?” Another, thinking back on the Upper West Side parties he no longer attends, told me, “Every time I’d say to someone, ‘No, I don’t think all criminals are victims,’ or ‘Yes, I do think welfare does harm,’ another jaw would drop, and someone else would accuse me of being a monster. After a while, my reaction became, ‘Okay, fine, these people aren’t my friends anymore. That’s the way it is, and the hell with them.’”

But women, annoying as the fact may be to biology-be-damned feminists, are wired differently, and seem to feel these losses more keenly.

“There’s no question my world has narrowed,” as the Manhattan Institute’s Kay Hymowitz puts it, with a note of at least quasi-regret, “and my social life has been greatly diminished. I actually used to stay up at night, thinking, ‘I should’ve said this, I should’ve said that’ - like the kid feeling left out. One old friend basically let me know she can’t have me around anymore, just can’t fit me in, because I supported the war. To her, conservatives are all Darth Vaders, planning mayhem and war for the fun of it. And this now included me.”

All of which brings us back to the key question: Is it even possible to be genuine friends with someone who believes that you - or, if not precisely you, everyone who agrees with you - is a vicious, mean-spirited, greedy, bigoted S.O.B.? A bunch of liberal educators have actually created a scorecard that helps provide an answer to this question. Like most liberal initiatives, it is pitched to the mental/emotional level of your average six-year-old - the only difference being that, this time, six-year-olds were actually the target audience, the checklist having been created in reaction to the much ballyhooed “epidemic” of schoolyard insensitivity, once known as “childhood.” Anyway, for our purposes it provides a handy means of grading the performance of our liberal friends in the plays-nice-with-others department.

This being my book, I will take the liberty of handing out the grades:• Good friends listen to each other.

Do yours? Grade: F

• Good friends don’t put each other down or hurt each other’s feelings. Do yours? Grade: D

• Good friends can disagree without hurting each other.

Can yours? Grade: C-

• Good friends respect each other. Do yours? Grade: C-

• Good friends give each other room to change.

Do yours? Grade: F

Then again, who’s kidding whom? It’s not like such friendships have much of a payoff for those on our side of the fence, either. A casual bond with someone in the office or the neighborhood is one thing, sustained easily enough by the occasional give-and-take about the kids, or work, or the latest pop tart to disgrace herself publicly. But if you care as deeply as some of us do about the state of the nation and the culture, how do you remain tight with someone who quotes Keith Olbermann and Paul Krugman, or has no problem with campus speech codes, or can hear America compared to Nazi Germany and feel anything other than utter revulsion?

Old times’ sake being the fine thing it is, we often find ourselves hanging on, even as the returns diminish with each awkward conversation. “The common ground just kept getting smaller and smaller,” one woman says of a once-close friendship. “What to talk about became a real problem - because after a while, we couldn’t even talk about pop culture or shopping without hitting a land mine.”

“We still see each other on important occasions,” says someone else, “but that natural give-and-take is gone, and it’s all very superficial. How can there be a real friendship when you can never be honest or real?”

My wife and I know a couple, Paula and Alex, about which we feel exactly such a sense of loss. Paula and I were friends first, right out of college, when we briefly worked together, and when our respective spouses happened along, we clicked as a foursome. We had a great deal in common - including, back then, the usual gamut of liberal attitudes and assumptions - and over the years they’ve been kind and generous friends. We’ve spent innumerable pleasant evenings together, consulted each other regularly about life and careers, and watched one another’s kids grow up.

At first, when we began to diverge politically, it didn’t seem all that great a problem. Although outspoken about many things and given to hilariously blunt critiques of both the passing scene and many individuals in it, Paula had never been much interested in politics; her husband, while a liberal by birth and inclination, is a gentle soul, given to a bemused live-and-let-live-ism all too rare on the Left.

But at some point they got very chummy with a woman in their extended circle, a fairly well-known old-line feminist, someone who’d actually written finger-wagging books full of terms like “patriarchy,” “heterosexism,” and “hegemony.” Paula, who’d always been blithely indifferent to the raging culture wars, suddenly started coming out with the most astonishing statements of her own.

I can nail almost precisely the time and place when it became clear that the friendship was in serious trouble. It was between 9:30 and 10:00 on a Friday night in February 2005, over dinner at a Japanese restaurant in Manhattan’s West Twenties. Somehow, foolishly, we’d let the conversation wander onto the then-current firestorm involving Harvard President and future Obama Lackey Larry Summers and his critics on the left, feminists and their pathetic male fellow travelers. You’ll recall that Summers had committed the unpardonable sin of free and open inquiry by speculating that one of the reasons more men than women are to be found in the upper echelons of math and the sciences might be innate differences between the sexes.

The moment Summers’s name came up, Paula made clear that she did not regard his views as either commonsensical or in the spirit of free and open inquiry. “You know what I wish?” she asked, smiling, as if certain everyone present would agree. “That he would be reincarnated as a woman.”

I caught my wife’s look at that instant, and understood that we’d crossed a Rubicon; she may still have been fond of Paula, but I could see the respect melting away. There followed a brief, intense back and forth, in which we more or less made our feelings known, before both sides backed off in deference to our shared history.

But I know how we talked about that moment on the way home, and, knowing them, have little doubt about how they talked about us. As the philosopher Blaise Pascal once observed, “Few friendships would survive if each one knew what his friend says of him behind his back.”

So, yes, I still have deep, deep affection for them. We still see each other from time to time, and are always careful to avoid land mines. But what mattered most, the ease that comes with the certainty of shared values, is irretrievably lost.

Only here’s the thing: In recent years, individually and as a couple, we’ve forged a variety of new friendships. Just about my favorite few hours every month are the ones I spend over lunch with my fellow contributing editors at City Journal, the quarterly of the conservative Manhattan Institute, trading thoughts, kibitzing, and occasionally having at each other, on politics and policy. It’s a great comfort to know that no matter how much we might disagree on waterboarding or the utility of vouchers, those differences pale beside our shared bedrock beliefs and principles. “That’s the lifeline, people who are on the same page,” Kay Hymowitz, one of those new friends, sums it up, “people who don’t make you feel” - she laughs - “weird.”

“What really struck me is the intellectual environment I found on the right,” adds Marlene Mieske. “I can sit around with other conservatives, and know that even if I say something they find outrageous, I won’t be ostracized - I’m still family. As a former liberal, I can’t tell you how refreshing that is.”

What’s especially satisfying, and more than a little startling, is how many of my oldest friends have made the same intellectual and moral journey from left to right as I have. Among these is a guy named Cary Schneider. We met way back in journalism school, when we were twenty-one - slightly younger than our sons, close friends themselves, are today. Cary and I talk at least three times a week, everything from baseball and work to politics and movies. Though there’s a lot of kidding around, it is all undergirded, as it always has been, by a double-wide-load of common assumptions. Only now these assumptions have largely to do with the lunacy of our former creed, liberalism, and the incalculable damage it has visited upon the land.

My wife has a friend like that, too, a woman named Jenny, with whom she grew up in Northern California, and likewise went to Berkeley, moved east and, glory be, also ended up on the Right and largely isolated. She and her husband Gerry live in a small Connecticut town a couple of hours away, and late on Election Day afternoon, we drove up there to wait out the coming storm together. Except it never came - never, at least, penetrated the walls of their home. We sat up late before the fire, bellies full of braised short ribs and mashed potatoes, wine glasses in hand, talking, interrupted only occasionally by their teenaged son, who was monitoring the TV. Gloomy as his reports were, among such friends, things didn’t seem nearly so cataclysmic. The women reminisced about the Monterey Pop Festival, where as teens they both worked shepherding zonked-out rock legends to their hotels; Gerry, who teaches English at an inner city vo-tech high school, told mesmerizing stories about his battles with administrators to teach Shakespeare instead of the Alice Walker and the rest of the P.C. crap on the approved list, and how, once he won, the kids blossomed in their belated exposure to the Bard.

Then, briefly, the spell was broken. “I already arranged to take a sick day tomorrow,” said Gerry. “I knew I wouldn’t be able to stomach the other teachers’ gloating.”

“Oh, c’mon,” snapped Jenny. “Londoners survived the Blitz, we’ll survive this.”

“Gosh, Jen, I wish we lived closer together,” cut in my wife, going sentimental. “You, us, Cary and Lucy, Kenny and Carol. . .”

“A commune!” Jenny laughed. “There’s a hoary old idea that’s come and gone.”

“And maybe should come again, for conservatives, under Obama.”

We all laughed. But at that moment, the idea didn’t sound half bad.