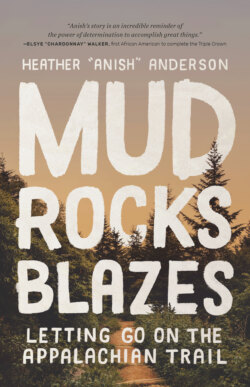

Читать книгу Mud, Rocks, Blazes - Heather Anderson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 RESTLESSNESS

ОглавлениеWATCHING THE PALE-GOLD HARVEST moon crest the foothills as I drove home, I recalled the last full moonrise I’d seen while crossing the flanks of North Sister in central Oregon. Its beams had turned Obsidian Falls into a ghostly veil as the water plummeted over the brink—the only sound in a silent wilderness. I remembered how I’d walked through fields of obsidian, like glittering black diamonds under my feet. Then I turned into my driveway, and blinked back the tears. My body was here, but my heart remained in the wild.

A few weeks after my run along Bellingham Bay, I found myself driving upriver at dusk, thinking existential thoughts as I gained on the mountains. Moments from the PCT replayed themselves on the movie screen inside my mind. I sang along as the radio proclaimed, “Nothing scares me anymore,” the only phrase I could identify with in an ocean of vapid lyrics.

I found a comfortable spot to sleep a stone’s throw from the trailhead, but the roar of Canyon Creek kept me awake. Five thirty arrived as it always did—too early—and I ate an almond butter sandwich in the pre-dawn light. It was the most normal thing I’d done since reaching Canada over a month before.

My dreadlocks, swollen by the humid air, bounced freely against the back of my neck as I ran along a ridge bathed in midday sun. The arduous climb up to McMillan Park had felt abnormally swift. Over and over I checked in with my body, awed at how effortless it felt to run through the mountains.

My body must be recovered from the PCT because it’s handling this forty-mile run today as though it is nothing.

I didn’t push. I simply reveled in the beauty of the wild and my body moving through it—free of the weight of a backpack. I was vaguely aware of reaching landmarks sooner than I expected, but it didn’t really matter. I was home—wild and free—in a hazy realm of sunshine and weightlessness. Less than eleven hours later my feet pummeled the mighty bridge over boisterous Canyon Creek. I whooped with the joy of it and worked my way down to the rocky shoreline. Fully clad, I lay down in the glacial creek, letting the water roll over me until I went numb. My joy flowed downstream, draining from my heart and limbs along with the heat of my effort. Instead of sleeping at the trailhead again, I would drive downriver to a cabin beneath the cedars and fall asleep in a bed. Tomorrow, there would be no wandering in the alpine. Shivering, I headed for the car.

There is an ebb and a flow to life post-hike. I feel moments of utmost contentment, knowing that I accomplished something mind-boggling, whereas other moments I gaze out the window, wondering if I merely dreamt it. In still other moments, the absence of focus, miles, and freedom to walk sends me spiraling into despair, and I grieve. Life feels empty when the trail is over, even when it’s full. The memories are like those of a loved one who is gone forever—with a churning in my stomach and an ache in my soul mixed with bittersweet joy. Having loved and lost—having hiked and come home—is better than never having hiked at all. Only time, and perhaps another journey, can mend the wound, though I know I’ll be scarred forever. I say, “Never again,” over and over, but it is a lie, a lie I tell myself when the grief overwhelms me. In the end, my memories of the trail are what make me feel whole. Despite the scars, loss, and depression, I know I will seek it again. For the joy, beauty, focus, drive, depletion, pain, and chance to achieve the impossible are simply too alluring. Just as I cannot hike forever, neither can I walk away for good.

Within the first week of finishing the PCT, I had stopped reading the comments of online articles about my fastest known time. The viciousness of internet personas both mystified and wounded me. Why critique the hike of someone they didn’t even know? Or speculate about my motivations? My choices? Yet, I continued to answer the email requests to speak about my hike from Scouts, hiking clubs, schools, and outdoor stores. Each time I recounted my story the trail felt so real I could nearly hold it in my hand. But then I would go home and it slipped away, sand between my fingers. Lying awake in bed afterward, I would clench my fists, trying to sense it again.

I began to collect print articles about my hike in a shoebox under my bed, which quickly overflowed. The articles filled me with a sense of wonder. The woman they described sounded superhuman. Her story was incredible. And she was a complete stranger. One even stated that my life prior to setting the record was unremarkable. As though I had simply appeared out of nowhere to hike the entire PCT in 60 days, 17 hours, and 12 minutes.

Perhaps she was a superhuman stranger. Had I made her up? I was weak. I was always the mid-pack runner in every race. I labored to keep up on the ascents. My body was too broken. I’d been sick and out of shape when I’d started my hike. I could not be that woman.

Yet I could remember every detail with wrenching clarity. Each moment of every day was permanently etched into my memory. I could sit and write for hours, recalling every second. But perhaps the record had been an accident. Maybe the reason I didn’t recognize that woman was because I knew that I wouldn’t have succeeded without more than a fair amount of luck.

To find Anish—the woman I was on the trail—I knew that I had to once again reach my limit. Only then could I ask her whether the record had been an accident, whether she and I were truly the same person. Although I’d lost her to daily life, that woman from the magazine articles must exist inside me somewhere. And only she could quell my fears.

Everyone I met clamored to know what was next. As though I owed the world an encore, as though putting myself through the travails of transformation once was not enough. Maybe they were right. Maybe I did owe them—and myself—that encore. To prove I was no accident.