Читать книгу Mud, Rocks, Blazes - Heather Anderson - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6 PREPARATION

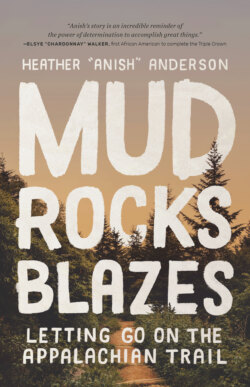

ОглавлениеI’D CONTEMPLATED ATTEMPTING the self-supported speed record on the PCT for years. The thought of someday trying it had given me hope when my marriage dissolved, when other relationships ended, when I quit my job and wandered aimlessly for eight months. Always, the trail was there, as something I wanted to do, something I was terrified of, and yet something I was convinced I had to try. Always. Stepping away from the southern terminus at the start of the PCT had been the most terrifying moment of my life. Reaching the northern terminus—essentially rebirthed—had been the most visceral. Now, despite forswearing FKTs and, to some extent, long-distance hiking, the white blazes of the Appalachian Trail were inexplicably calling me.

“I can’t believe I’m planning another two-thousand-plus-mile FKT,” I muttered to myself as I ordered Awol’s Appalachian Trail guidebook and downloaded the Guthook navigation app to my phone. A long row of Priority Mail Flat Rate boxes containing food, shoes, socks, and other supplies sat in the hallway, waiting to be taped shut and mailed. I sighed, turned off the light, and crawled into bed.

In the morning my boyfriend and I got in the car and headed north to Canada for a weeklong mountaineering trip. During that expedition, I couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that I needed to call my mom. We returned to cell reception five days later, and the news that my mother had suffered a severe stroke the day we’d left for Canada.

Two weeks afterward, I stood in my parents’ tiny living room, trying to explain my upcoming hike to my father.

“This is what I do now, Dad. I’m a professional hiker. I have sponsors helping me. If I set the AT record it will be a really big deal. I’ve put everything I have left into this hike.” I need this hike as much as I need food or air, I added mentally.

“Are they paying you?”

“Well, no. I don’t get paid. But they’ve donated gear and food to help me.” I paused, searching for further words of explanation, and finding that I did not have them. “I just have to do this.”

My father shrugged and leaned over the arm of his recliner to aim the remote at the TV behind me. The volume of The Andy Griffith Show rerun increased. Our conversation was clearly over. He’d spent thirty years building cars for General Motors, trading his time for a paycheck to sustain himself and his family. It was a tidy equation—one that was easy to understand. Yet, somehow, he’d raised a daughter who did not follow a neat mathematical path. Her rocky route was unfathomable to him.

I went into the dining room and sat at the table. Opening my laptop, I thought of my mother—in the hospital—barely able to speak. I thought about the rocks, roots, and mud that awaited me on the Appalachian Trail. Then I turned my mind to the process of planning my upcoming hike.

After numbing hours of scouring maps, plotting campsites, and making copious notes in my spreadsheets, I exhaled deeply and slipped into running shorts. Outside, in the oppressive humidity of the Midwestern summer, I ran down a dirt road, under a blue sky dotted with promising clouds.

As I ran, I passed corn fields bordered by ditches full of mullein, chicory, staghorn sumac, and Queen Anne’s lace. It was a landscape familiar to me in ways the peaks of Washington were now. I felt a sense of home, just as I did on mountain trails. My feet rhythmically struck the packed dirt and I sweated profusely in the ninety-degree heat.

How can I feel at home in so many places? Even ones so different from each other? The stress flowed out of me and into the wideopen air as I ran. I knew that if my feet took me there, I could always find a home in nature.

A week later we brought my mother home from the hospital. I sat down across from her at the table and held her hand. It had been over a month since her stroke and she still struggled to find words and create sentences. I wondered if I’d ever be able to sit and talk freely with her again.

“Mom, it’s time to go. I’m sorry I can’t be here right now, but Dad and Sis will take care of you. You’re going to be ok.”

She nodded and squeezed my hand. “I know.”

I’d offered to stay, but she’d insisted I go. As much as my father did not understand or support my path, my mother in more than equal measure did. She knew hiking was my life, even if she was worried—even though my dad could not comprehend it. She had known from the moment I took her to the white-blazed streets of Hot Springs, North Carolina in the fall of 2003 that I was meant to do something different: to walk a wild and mountainous path.

“I promise. This is the last time I try a multi-thousand-mile FKT. I promise.”

I wrapped my arms around her and we cried. No matter how many times we bid goodbye to one another we always cried. The drumbeat of both our hearts had always been in sync. I vowed to never again ignore my gut if it told me to call home.

I turned to my dad and hugged him awkwardly. “Goodbye, Dad.”

I picked up my backpack, and walked out the door.

The plane landed in Manchester, New Hampshire, a few hours later. My best friend, Apple Pie, and her husband, Greenleaf— both avid thru-hikers—picked me up at the curb and we headed north. The sun was shining and I marveled at the lushness of it all: the Oz-green landscape, thick deciduous timberlands, and the shining lakes and rivers. I felt a twinge of nostalgia. Here in the Appalachians, I was also home.

We made ourselves comfortable in a suite at a hostel in Millinocket, Maine. I laid out my gear: a Gossamer Gear 40-liter backpack, a Zpacks Solplex tent, a quart baggie of first aid supplies and ditties, two headlamps, a sleeping pad and bag, fleece sleep clothes, a rain jacket, poncho, trekking poles, a Sawyer Squeeze filter, and a few other things. One item at a time, I carefully repacked, trying to relax, but my body and mind were in overdrive. They knew what was coming. I knew what was coming. My resolve wavered, and I batted the ideas of quitting versus following through back and forth.

“What the hell am I doing?” I muttered to my gear.

I showered and lay down on the bed. I had no more confidence I could complete this FKT than when I left Campo to start the PCT two and a half years before. But I did have the same sense of destiny. I knew that I had to try. I would attempt to hike the 2,189-mile-long Appalachian Trail faster than anyone else had. I would do it alone and not to prove anything to anyone this time except myself—unlike the JMT, this hike was more than an attempted encore. It was eight months to the day from my dream of following the white blazes. There was something I needed to learn out there on the rocky, rooty trail.

“I just don’t know what it is,” I whispered, before closing my eyes and trying to sleep.