Читать книгу Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirits - Heike Behrend - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOne

Troubles of an Anthropologist

The Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena

In August 1986, Alice Auma, a young woman from Gulu in Acholi in northern Uganda, began raising an army, which was called the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces (HSMF).1 From a local perspective, she did this on orders from and as the spirit-medium of a Christian holy spirit named Lakwena. Along with this spirit who was the Chairman and Commander in Chief of the movement, other spirits – like Wrong Element from the United States, Ching Po from Korea, Franko from Zaire, some Islamic fighting spirits, and a spirit named Nyaker from Acholi – also took possession of her. These spirits conducted the war. They also provided the other-worldly legitimation for the undertaking.

In a situation of extreme internal and external threat, Alice began waging a war against Evil. This evil manifested itself in a number of ways: first, as an external enemy, represented by the government army, the National Resistance Army (NRA);2 and secondly, as an internal enemy, in the form of impure soldiers, witches, and sorcerers.

In November 1986, Alice moved to Kitgum and took over 150 soldiers from another resistance movement, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA), which was also fighting the government. In a complex initiation ritual, she purified these soldiers of evil and taught them what she termed the Holy Spirit Tactics, a special method of fighting invented by the spirit Lakwena. She instituted a number of prohibitions, called Holy Spirit Safety Precautions, also ordered by the spirit Lakwena. With these 150 soldiers, at the end of November she began attacking various NRA units stationed in Acholi. Because she was successful and managed to gain the sympathy of a large part of the population even outside Acholi, she was joined not only by soldiers (from other movements), but also by peasants, school and college students, teachers, businessmen, a former government minister, and a number of girls and women.

The HSMF marched from Kitgum to Lira, Soroti, Kumi, Mbale, Tororo, and as far as Jinja, where they were decisively defeated at the end of October 1987. Alice had to flee to Kenya, where she was granted political asylum, and she is alleged to be living in northern Kenya today.

The war in northern Uganda did not come to an end with her defeat, however, for the spirit Lakwena did not give up. He took possession of Alice’s father, who continued fighting with the remaining soldiers of the HSMF until he surrendered to the NRA in 1989. In addition, Lakwena took possession of a young man named Joseph Kony, who continued the war against the NRA up to the present.

Mass Media and Feedback

When I began my work, the subject of my research, Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement (HSM), had no place in the books and articles of my colleagues; it had not yet been taken up in scientific discourse. But I did not have the privilege of writing the first text on the movement, for the HSM had already been created by the mass media.

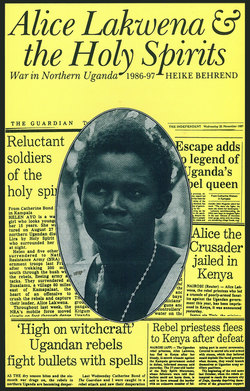

In 1986, when a young woman in Acholi, in northern Uganda, began creating an army on orders from a holy Christian spirit, this was not really noted as an event. Not until she had inflicted severe losses on the government army in several battles, especially the battle at Corner Kilak, and marched on the capital, Kampala, was she seized upon not only by the local but also by the international mass media. The press created the images and stereotypes that would shape discourse on the HSM. In local and international headlines, Alice was designated as a rebel or voodoo priest, a witch, a prophetess, a former prostitute, the future Queen of Uganda, and a Jeanne d’Arc in the Ugandan swamp. Jeanne d’Arc, too, was called a saint and a prophetess and was reviled by her enemies as a prostitute and a witch.) Her movement was depicted as a bizarre, anachronistic, suicidal enterprise in which hordes armed only with stones and sticks were conducting a senseless struggle.

The reporting addressed a topic that will be treated extensively in what follows, namely witchcraft and sorcery. In New Vision, a Ugandan daily paper loyal to the government, Alice was called a witch doctor as early as 21 March 1987. And on 3 April 1987, one could read: ‘The extraordinary casualties rate suffered by the rebels is largely explained by their continuing reliance on witchcraft as a means of primitive mobilisation.’ This was followed by a report that provides a typical example of war propaganda:

Alice murdered a child in a ghastly ritual sacrifice after the second attack on Lira 21 March [1987]. Lakwena found a woman who had twins and took one of them. The child was then killed and its liver eaten by the rebel soldiers. The sacrifice3 was intended to strengthen rebels through witchcraft . . . (New Vision, 3 April 1987).

It is commonplace that charges of witchcraft and cannibalism are among the stereotypes used to designate those to be excluded: the other, strangers, and enemies (cf. Arens 1980). War propaganda in the First and Second World Wars also employed this theme (cf. Fussell, 1977:115ff.).

The Holy Spirit soldiers did not remain uninfluenced by the mass media. They listened regularly to the radio, especially the BBC and Deutsche Welle. They also read newspapers and magazines. They heard and read the reports and reportage on themselves and their struggle. Their own significance was conveyed to them in the media.4 They learned how they were seen by others and attempted to live up to, as well as to contradict, the images drawn of them.

In an interview Alice – or rather, the spirit Lakwena – granted reporters a few days before her defeat at Jinja, she tried to correct the picture the media had sketched of her and her movement. She announced in the Acholi language (which one of her soldiers, Mike Ocan, translated into English) that the spirit Lakwena was fighting to depose the Museveni government and unite all the people in Uganda. She said that the war was also being conducted to remove all wrong elements from the society and to bring peace, and that she was here to proclaim the word of the holy spirit (Sunday Nation, 25 October 1987). In addition, she demanded balanced reporting (Allen, 1991:395).

Alice and the Holy Spirit soldiers were aware of the power of the mass media, and tried to build up a counterforce to meet it by setting up a Department of Information and Publicity within the HSM. It produced leaflets giving information on the goals of the movement, distributed them among the populace, wrote letters to chiefs and politicians, and also collected information. A radio set was available and a photographer took pictures of prisoners of war, visitors, captured weapons, and rituals. The Holy Spirit soldiers wrote their own texts. They kept diaries; the commanders and heads of the Frontline Co-ordination Team (FCT) drew up lists of casualties, recruitments, and gifts from civilians; they kept minutes of meetings and composed reports on the individual battles. And the chief clerk, Alice’s secretary; wrote down what the spirits had to say when they took possession of Alice, their medium. Individual soldiers also noted in school notebooks the twenty Holy Spirit Safety Precautions, rules the spirits imposed on them, as well as prayers and church hymns. And pharmacists, nurses, and paramedics noted the formulas for various medications invented by the spirit Lakwena.

The HSM documented itself and produced its own texts in answer to the mass media. Composing these writings was an act of self-assertion, an attempt to have their truth, their version of the story prevail against others. In a certain sense it was also a magical act with which they fixed a reality that became more real through the very act of writing.

But even the attempt to shed the images and stereotypes of the mass media had to take their power into account. Some of these images remained powerful even in the opposing texts.

Field Research in a War Zone

Ethnography is currently conducted in a world in which the commodities of the Western and Eastern industrial countries – such as Coca-Cola, transister radios, sunglasses, clocks, cars, etc. – are found everywhere, including on the peripheries. And although it appears as if the differences between the various cultures are increasingly being levelled to produce a homogenous world (Kramer, 1987:284), ethnographic works have shown (cf., for example, Taussig, 1980; Appadurai, 1988; Werbner, 1989:68; Comaroff and Comaroff 1990) that the people of the so-called Third World adopt and transform these wares in their own independent way. The commodities develop their own life-history and their own meanings; sometimes they are transformed into status symbols or are integrated in a sacred exchange, thus even losing their character as commodities. Torn from the context of our culture, they confront us again in another context, one which is foreign to us. We think we recognize them as our own, and yet, when we look at them closely, they appear alien or at least alienated.

It is no longer ethnographic comparison that brings the objects of our culture and of other cultures together; rather, they confront us side by side, already brought into a new context in cultures which are foreign to us. Perhaps recognizing familiar things in a foreign context allows us to define more precisely the difference that exists between the meanings which are familiar to us and the new meanings in another context.

Not only goods produced in the West, but also mutual information and knowledge of each other reach the peripheries of our world via the mass media. In this way, the anthropologist and the subjects of his field research are a priori familiar and known at the same time as they are strange to each other (Marcus and Fischer, 1986:112). As already noted, the mass media also affect what we have up to now called ethnographic reality. They deliver pre-formed images to be relived. They create feedback. Ethnographic reality can no longer be assumed to be ‘authentic’; rather, we anthropologists must consider how it is produced – and what models it imitates.

Since centres and peripheries influence each other, we can no longer speak of independent, self-sufficient cultures, which were long the classic analytical units of ethnology (ibid). And thus the dichotomy, so customary in anthropology, between the ‘traditional’ and the ‘modern’ has also lost its validity (cf. Ranger, 1981).

It is already becoming apparent that in future, anthropologists will increasingly be confronted with an (ethnographic) reality that they themselves (together with the subjects of their research) have created. When I talked with Acholi elders in northern Uganda, I could not fail to note that my discussion partners had already read, and were reporting to me from, books and articles that missionaries, anthropologists, and historians had written on their culture and history. Thus I encountered in their answers not so much authentic knowledge as my own colleagues – and, in a sense, myself. I also discovered that a number of local ethnographies and historiographies already existed that had been written by Acholi like Reuben Anywar, Alipayo Latigo, Noah Ochara, Lacito Okech, and R. M. Nono,5 to mention but a few. The texts of Europeans, especially those by missionaries from the Comboni Mission, by Crazzolara on the history of the Lwo (1937), and by Pelligrini on the history and ‘tradition’ of the Acholi (1949) found entry into these indigenous texts. So I had to ask myself whether the Acholi elders were telling me their or our story (cf. Bruner, 1986:148f.) and what that meant for distinguishing the interior (emic) from the exterior (etic) view (ibid). Bruner, who sought an answer to these questions in his research on the Pueblo Indians of the United States, assumes that Pueblo Indians and the anthropologists who write about them share the same discourse.

My position is that both Indian enactment, the story they tell about themselves, and our theory, the story we tell, are transformations of each other; they are retellings of a narrative derived from the discursive practice of our historical era (Foucault 1973), instances of never-ceasing reflexivity. (Bruner, 1986:149).

I agree only with part of this statement. For one thing, Bruner neglects the historical perspective, which is precisely where we can trace how a dominant discourse takes over. For those ethnographed, the subjects of our field research, do not share our discourse from the beginning. They put up resistance to their colonization and ‘invention’ (Mudimbe, 1988) and designed counter-discourses, even if (as will be shown in this study) these finally confirmed the hegemony of the European discourse (cf. Comaroff and Comaroff, 1991:18). But it is precisely the history of the hegemony of our discourse which also makes clear the difference that arises from the often original interpretation of the dominant discourse that the ethnographed come up with. In future, noting this difference as precisely as possible may be the ethnographer’s primary goal.

From the outbreak of the fighting in May and June 1986, northern Uganda became increasingly isolated from the rest of the country. The NRA government declared the Acholi District a war zone. Roadblocks controlled access. Transport and trade collapsed almost completely towards the end of 1987. As early as March, the NRA forced a large part of the population in Acholi to leave their farms and take ‘refuge’ in camps or in the city. But, I was told, many fled less from the so-called ‘rebels’ than from the soldiers of the NRA, who plundered, stole livestock, and burned houses, supplies, and fields.

In November 1989, I was able to visit northern Uganda – Acholi – for the first time. Most of the more than 150,000 refugees the war had created had now returned to their villages and begun to cultivate their fields. Following a government offer of an amnesty and a peace treaty with another resistance movement, the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA), thousands of ‘rebels’ left the bush, returning to their villages or joining the NRA and militias to fight against their former allies. A few bushfighters who refused to surrender joined up with the Holy Spirit soldiers of Joseph Kony. They conducted a guerrilla war, staging ambushes here and there or daring an occasional attack.

The NRA seldom managed to catch Holy Spirit soldiers, and all too often vented their frustration on the local populace. After each defeat, they took vengeance on innocent people. The result was that the population indeed sympathized more or less with the Holy Spirit soldiers, though they too degenerated more and more into marauding bands of thieves.

In November 1989, Gulu, the capital of Acholi District, was a city ‘occupied’ by the NRA. Trucks carrying soldiers and weapons careered down the main street. Soldiers sat in small bars, rode bicycles, or strolled the streets in groups, singing songs. Some had tied chickens they had acquired to the handlebars of their bicycles, carried them in their knapsacks, or strapped them to the counter of the bar while they drank. The traces of the war had not been eliminated. Many houses lining the main street had been destroyed, their facades burned, the pavements torn up, the street signs perforated by bullets and twisted, and the central roundabout, once planted with glowing red bougainvillea, now consisted of nothing but a heap of stones. The scantily covered dead were carried on stretchers through the city followed by weeping relatives. One woman told me there had been too many dead taken by the war and now by AIDS as well.

While the war continued in the territory surrounding Gulu, and distant gunfire could often be heard, in the afternoons, and especially in the evenings, the sound of machine gun fire also emanated from the video halls in town where low-budget American films or karate films from Taiwan staged a reprise of war. These films provided the models avidly imitated by Holy Spirit soldiers and government troops alike. Soldiers I got to know gave themselves names like ‘Suicide’, ‘Karate’, ‘007’, and ‘James Bond’. And a spirit who liked to introduce himself as ‘King Bruce’, after the karate hero Bruce Lee, fought in the Holy Spirit Movement of Joseph Kony.

I did not pitch my tent in the middle of an Acholi village, as Malinowski exhorted, but took up my quarters in what had been a luxury hotel in town. I was advised to do this because I was told that the Holy Spirit soldiers still made the territory around Gulu insecure. Especially at night, ‘rebels’, militiamen, and government soldiers moved about in small groups plundering farms. Since they all wore the same uniforms, one could never be sure who the plunderers were. In the evenings, many people, especially women with children, came to the city to seek protection from such marauders, spending the night there then returning to their villages in the morning. Others, who lived too far from the city, were so afraid of the soldiers that they slept in the bush. The children were wrapped in blankets and hidden separately under certain trees or bushes. They were warned not to make a sound, whatever happened, and not to come back to the house until morning, when it was light again.

The hotel I stayed in had been plundered twice, once by Idi Amin’s soldiers, who had fled from the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) in 1979, and a second time by Bazilio Okello’s followers, who took flight from the National Resistance Army (NRA) in March 1986. Most of the windows were broken, and all the transportable furniture had been taken away. The doors had been smashed and could no longer be locked; the rooms contained nothing but a bed. In the evening, I was the only guest. The waiter put on livery in my honour and the kitchen boy arranged a bouquet of bougainvillea.

Under the conditions of a continuing war, it was impossible for me to carry out field research in the classic sense. George Devereux has shown that methods are a favoured means of reducing anxiety. Method derives from the Greek hodos, i.e. a path or road. Methods are paths one takes together with other scientists. They calm the feeling of insecurity; after all, one is not taking the path alone. But the information I was collecting for my work was not the only frightening thing; there were also the situations in which I had to collect it. I am sure I have not managed to understand what happened without displacements and blind spots (Crapanzano, 1977:69). Speaking of the unspeakable and making it my topic sometimes seemed the only escape. But my wish that everything not be so terrible was also very strong. At some point, I noticed that I tended to conduct discussions mostly with members of the Holy Spirit Movement who had been in its civilian wing and who had not themselves fought and killed.

During my study of anthropology and while conducting field research among the Tugen in northwestern Kenya, I had learned to defend the people on whom and with whom I was working. Here, too, I now wanted to sketch a picture of the HSM which showed them from their own perspective and in correspondence with their self-image, against the discrimination of the mass media. I assumed that the Holy Spirit Movement, like so many others, was a peasant revolt against the state; and I planned to take their side more or less clearly. But I was soon forced to realize that most of the original members of the Holy Spirit Movement were not peasants, but soldiers who had fought in the 1981–5 civil war and who could not or would not pursue any other occupation than waging war and killing. Their goal was to get rich, take their revenge, and regain the share in state power they had lost. I played with the idea of giving up my project, since I saw no possibility of depicting the Holy Spirit Movement and its history except by idealizing it unjustifiably or repeating stereotypes that would have been too close to certain colonial images of warlike, violent ‘savages’. Not until I talked with a former Holy Spirit soldier who had fought alongside Alice Lakwena from the beginning did I learn of the HSM’s serious attempt to wage a war against the war and to put an end to violence and terror; only then did I manage to regain the sympathy for the ‘object’ that seemed to me to be a necessary precondition for ethnography. And although I tried to trace the inner kinship of humanism and terror as well as the double movement of liberation and enslavement (cf. Habermas, 1985:289) in the history of the HSM, this precondition may, I fear, be to blame for a certain tendency to idealization in my depiction. My discussion partners, who used me and my work to justify their own past, also exhibited this tendency.

The postmodern call for heterogeneity (for example, Lyotard, 1977; Derrida, 1988), for interpretations that not only call forth counter-positions, but which also take account of what lies in between or alongside, is very difficult to fulfill in ethnographies (on war), because in such a situation one indeed thinks in oppositions and in opposition to something. But I hope, especially in the historical chapters, that I have brought to light the transitions, that which lies between the oppositions (cf. Parkin, 1987:15).

I conducted a number of extensive discussions, sometimes over periods of several days, with some fifteen former Holy Spirit soldiers in Gulu and Kampala. Their willingness to talk to me was rooted in the task the spirit Lakwena had assigned them of correcting the false image the government had spread about the movement in the mass media. Many of them still acted on behalf of the spirit, even though they had left the movement.

All of them, with one exception, made me promise not to mention their names in my text. The exception was Mike Ocan, a former member of the civilian wing, the Frontline Co-ordination Team of the HSM. He had been taken prisoner after the fighting in Jinja in October 1987, had been in prison, had been ‘politicized’ in a camp, and afterwards rehabilitated. When I got to know him in the Spring of 1991, he was working as headmaster at a school in Gulu. He had already served as an informant to Apollo Lukermoi (1990), a student writing a thesis in Religious Studies and Philosophy at Makerere University, and he felt himself called to be the historiographer and ethnographer of the Holy Spirit Movement. Since he was on the side not of the victors but of the defeated, he was under great pressure to explain himself and under a greater burden of proof than a victor, for whom success itself speaks (cf. Koselleck, 1989:669).

He derived his ethnographic and historiographic authority (cf. Clifford, 1988) from being an eyewitness and a participant, which he considered an epistemological advantage that assured the truth of his story (ibid:668).6 But he also appealed to the authority of an otherworldly power, the spirit Lakwena. In the text he gave me, he wrote: ‘The Lakwena bestowed upon me the authority to inform the world about his mission on Earth and I feel in duty bound to do so.’ Just as the Holy Spirit Movement legitimated itself transcendentally with reference to the spirits, Mike Ocan adopted this legitimation for his story.

At my request, he wrote the ‘first text’ about the HSM, a ‘thick description’ in Geertz’s sense (1983). He thus gave the past the status of a written story and, by putting it in writing, irrevocably fixed the difference between the story that had passed and the linguistic form it had now gained (cf. Koselleck 1989:669).

But this text is also an attempt to translate the organization of the Holy Spirit Movement, its content, goals, meanings, and history, for a European audience. Anthropologists are not the only ones confronted with the problem of translation; the same is true for those who try to produce a text that crosses cultural boundaries. It is in this context that we must place Mike Ocan’s assurance at the beginning of his text that ‘the accounts here contained are by no means fictitious. They are real life experiences which took place a couple of years back.’ The distance from events that a text for Europeans required from him permitted him to recognize the ‘exoticism’ of the Holy Spirit Movement and its history. But perhaps it was also the influence of the mass media and the stereotypes and images from an external perspective that led him to defend his own text as non-fiction. With this remark, he also sought – in the best anthropological tradition – to enhance once more the truth of his portrayal.

In 1995, Mike Ocan and I visited another intellectual of the HSM. Like Mike Ocan, he had been working in the Frontline Coordination Team and, in addition, as the secretary, or chief clerk, of Alice Lakwena. The first question he asked me was if I believed. Hesitantly, I said that I would believe and take seriously what other people believed. This answer obviously did not please him. ‘Do you believe that when bombs are falling and you believe and pray and I put up my hand against the sky the bombs stop falling? Do you believe that when you believe and bullets are coming straight towards you they start encircling you without hitting or injuring your body?’ He asked Mike Ocan to give other examples which Mike did. Both started talking passionately and somewhat nostalgically about the old days in the HSM. And I suddenly realized something of the atmosphere that at certain times must have prevailed among the Holy Spirit soldiers, an atmosphere of powerful enthusiasm and absolute trust in God, the spirits sent by Him, and the believing self. This aspect has been excluded almost completely from Mike Ocan’s text and my interpretation. Mike Ocan knew very well the difference between belief and knowledge, and in his text he presented the latter as I had asked him to do. In the short encounter with the chief clerk, however, I had the chance to get a glimpse of this powerful force called belief, which is not treated in this book.

Mike Ocan’s text is the essential foundation of this book. It also formed the basis for a long dialogue he and I conducted on the Holy Spirit Movement.7 Thus, we re-uttered the text and in this long conversation were able to give speech back its due.

Aside from Mike Ocan, I also conducted talks with some elders about Acholi macon, the Acholi ‘tradition’ and history. Special mention is due to R. M. Nono, who himself wrote an ethnography and history of Acholi, which I received after his death in the Autumn of 1990. I visited him often on his farm a few kilometres outside Gulu. We sat in the shadow of a mango tree, and he read to me from his manuscripts, which he kept in a briefcase made of goatskin. Again, his text was the basis for our talks.

In contrast to R. M. Nono, who was something of a self-styled historian and ethnographer of his own society, Andrew Adimola had studied at Makerere University and even published an essay on the Lamogi Rebellion in the Uganda Journal (1954). He had been a Minister under Idi Amin, but had left the country to organize resistance against the dictator from exile. He was a leading politician of the Democratic Party (DP), which was banned under Museveni. In the Spring of 1991 he and seventeen other people were arrested and accused of high treason. The charges had to be dropped for lack of evidence, and when I left Uganda in January 1992, he was a free man again. With Adimola I conducted talks primarily about the past and present political situations.

Along with these elders, Israel Lubwa, his wife Candida Lubwa, and their children provided essential help in my research in Gulu. Patrick Olango, their son, had returned to Uganda after studying ethnology in Bayreuth, and their two daughters, Carol Lubwa and Margaret Adokorach, worked as my research assistants.

Israel Lubwa had studied agriculture at Makerere and had been an agricultural officer during the colonial period. In our talks, he repeatedly stressed his own unsuitability: he said he could not be an authentic informant, because he had read too much. He was well aware of the epistemological problems that arise when ‘informants’ have read the books and articles published on their own culture and history. Some of the essential insights of this study emerged in talks with him.

With Mrs. Lubwa and her two daughters, Carol and Margaret, I talked primarily about witchcraft. The discourse on witchcraft is conducted mostly by women. Only in some cases is it adopted by men, which then makes it a public discourse.

Jeanne Favret-Saada (1979) has shown that, from the local perspective, no one ever speaks of witchcraft simply to learn something, but always to gain power. There is no disinterested talk about witchcraft, for the discourse on witchcraft itself already possesses real power (ibid:249). In conversations about witchcraft, the ethnographer loses his/her apparently neutral position and finds him/herself in a power configuration in which he/she is assigned a specific role. The three women were unable to speak with me openly (or more openly) on this topic until I myself began going to various witch doctors,8 who discovered that I, too, was a victim of witchcraft, whereupon they lifted the spell on me and put one on my enemy.

These witch doctors, who, as spirit mediums, divined and healed, considered it important that I should not remain an outside observer, but should become a client or, better still, a patient. They assigned me a clear place in their network of relationships and thus called on me to carry out what has been regarded as an ethnographic method since Malinowski: participant observation. I agreed, paid the registration fee, and presented them with problems resulting from my daily life in Gulu, in a situation of war, menace, and fear. Like Acholi women, I too visited one of these mediums almost every day and asked her to consult the spirits. These visits became part of my daily life and, by allowing me to speak of the menace and fear I felt, in a sense making them public and ‘treating’ them, thus helped me reduce, acknowledge, and at least partially deal with them. ‘I know . . . and nonetheless!’ – this attitude, which Favret-Saada described among French peasants (1979:77), was also mine in Gulu. Like them, I tried to satisfy my desire for security, while at the same time knowing this was impossible. And although I, and perhaps other women in Acholi, considered ritual procedures futile, they were consoling.

I was able to speak English with most of the discussion partners named here (and also those who remain unnamed). Only in dealing with some of the spirit-mediums did I have to rely on translation into English from the Acholi. Since primarily Kiswahili and English, along with Acholi, were spoken in the Holy Spirit Movement, I abstained from learning Acholi or Lwo. But I worked out the semantic fields of certain Acholi words that seemed to me indispensable to any understanding of the HSM and its history. In what follows, I shall present them. To make it possible to see when and in which context in the discourse of the HSM English, Kiswahili, or Lwo were used, in this text I have left the terms in their original language.

This study deals with war, destruction, violence, suffering, and death. I have not managed to do linguistic justice to the events, for no language can ever approach the events themselves. In his outstanding analysis of the literature on the First World War, Paul Fussell (1977) pointed out that only with Mailer’s, Pynchon’s, and Vonnegut’s writings on the Second World War was a dimension in the depiction of war achieved – ironically, only after the death of most veterans of the First World War – that permitted the description of the limitless obscenity of the Great War (ibid:334). I hope that subsequent studies will do more justice to the events described here.

Notes

1. As well as this self-chosen designation, the name Holy Spirit Movement was also used. In what follows, I use the two terms synonymously. Outsiders also spoke of members as the ‘Lakwenas’.

2. Since 1995, after establishing the new constitution, the NRA is now called the Uganda People’s Defence Forces.

3. Although some spirits (jogi) in Acholi demanded human sacrifice, all the Holy Spirit soldiers with whom I spoke on this topic denied that there had been human sacrifice in the HSM.

4. Fussell quotes a report on the Second World War in which the soldiers ‘had almost completely substituted descriptions which they read in the newspapers or heard on the wireless for their own impressions’ (Fussell, 1977:173).

5. All of whom wrote their texts in Acholi. With the exception of R. M. Nono’s text, I was not able to collect and translate their writings, because the manuscripts had been lost or destroyed in the confusion of the civil war.

6. In the European tradition, being an eyewitness, or better still a participant, was considered an epistemological advantage as late as the eighteenth century; but since the development of historical-philological criticism, growing temporal distance from past events has served as a warranty of better knowledge (Koselleck, 1989:668f.).

7. The generosity of the University of Bayreuth’s Special Research Programme allowed me to invite Mike Ocan to come to Bayreuth and Berlin to continue the discussion.

8. I use the term ‘witch doctor’ quite pragmatically, as English-speaking Acholi also do. In my chapter on the history of religions I examine more closely the history of the term and the almost discriminatory connotation it carries.