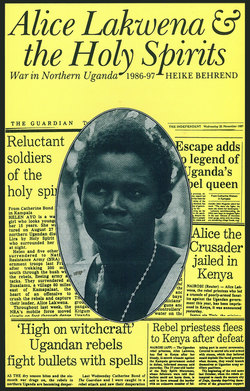

Читать книгу Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirits - Heike Behrend - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

JOHN MIDDLETON

On 2 January 1985, an Acholi woman from northern Uganda named Alice Auma was possessed by an alien Christian spirit known as Lakwena (‘Messenger’ in Acholi), and became known as Alice Lakwena. From this event ensued a powerful prophetic movement, the Holy Spirit Movement, and its very nearly successful military insurrection against the government of Uganda. Alice was still alive, a refugee in Kenya, when this book was published. A last report was of her sitting in a bar drinking gin and Pepsi-Cola: Lakwena had deserted her. Hers was a personal tragedy. But if we look behind her, as is done in this valuable book, we can discern a far greater tragedy, namely, the history of the many thousands of Acholi men and women who took her as their prophet and followed Lakwena’s message to put right the cruel and sinful world in which they lived, a message that led them to defeat and even greater misery. Alice’s Holy Spirit Movement failed: yet, like many ‘failures’ it transformed its country’s history.

Prophets and prophetic movements are nothing new in African history, but few prophets have been observed by outsiders. Many appeared during the colonial period in reaction to unpopular administrations; the colonial administrators considered the prophets to be rebels and tried to prevent outsiders from meeting them. A problem in studying them is that many prophetic movements have today been mythologized as national independence movements, and most of their prophets have become mythical personages. It is difficult to reconstruct events.

Many sanguine politicians expected that, after political independence, these movements would cease, but they have not done so. We should ask why these movements still appear and become strong enough to lead to overt political action. The people who take part in them are ordinary citizens and not crazed religious maniacs. Why do people follow self-proclaimed prophets, and why do they die for their beliefs? These are important questions, and this book provides some of the answers within a specific region at a specific time in history, rather than giving wholly ‘theoretical’ generalizations.

Heike Behrend was not able to meet Alice Lakwena; but she had contact with many of Alice’s former followers, in both Uganda and elsewhere, as she tells us in her introduction. Her research was as deep as was possible in the confused conditions of the time, and she managed to find many veterans of Alice’s movement who were willing to tell its history as they recalled it. Behrend writes without sentimentality of Alice’s followers, some of whom, after suffering cruel defeat by a brutal government army, themselves degenerated into a crew of predatory brigands.

Alice was originally one of many local Christian healers but only she appears to have become recognized as a powerful prophet. She organized and led the Holy Spirit Movement through its victories against the central government, then to its defeat and her final loss of authority when she became known as a mere witch doctor. At first she was the medium of an Italian military engineer, known as the spirit Lakwena, then later a medium for several alien spirits from America, Korea and Zaïre. Her authority was that of Lakwena himself and the other spirits who spoke through her body and voice; later she remembered nothing of what ‘she’ had uttered. These spirits possessed Alice on different occasions, and their various personalities and identities became known to her listeners as soon as she uttered their words. On another level considerable authority was exercised by the person known as the ‘chief clerk’ who summarized Alice’s words to those listening. There was a triad of spirit, medium and translator. Alice had three ‘chief clerks’ in succession, all men of education and knowledgeable about the entire Ugandan political situation. Towards the end of the Holy Spirit Movement they separated themselves from Alice when she began to ignore the rules of the movement, and her followers then blamed her for the movement’s defeat.

Why did so many people follow Lakwena and Alice? The immediate reason was that the leaders promised to rid the country of witchcraft. This might not ‘exist’ in actuality but beliefs about it did, as a dangerous sign of the evil that was taking over the land. The Acholi had suffered many years of wretchedness under Idi Amin, Obote and then Museveni, with continual military attacks and at times famine and sickness. The country was riven with dissension and greed, seen as the consequence of witchcraft; and the power of the enemy, the government, was also regarded as being based upon witchcraft. Alice and her spirits, as Christians, claimed first to rid northern Uganda of its ‘internal’ witchcraft and then to destroy the ‘external’ witchcraft throughout the rest of the country. Witchcraft, like armed violence, was a form of aggression, and Behrend discusses the links and analogies between them as being clearly at the heart of the movement.

The Holy Spirit Movement, and its military wing the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, were concerned with the purification of society from sin, especially as expressed in ‘witchcraft’. Sin, unlike the breach of taboo, was considered a deliberate act for which the sinner had to take responsibility before both the living and the Divinity. To defeat external sin required armed force; to defeat internal sin demanded spiritual purification, and once that was gained the soldiers of the Holy Spirit Movement would be victorious against the government army. Pure soldiers had no fear of enemy bullets but stood in line singing psalms, their spirits deflecting the bullets. Defeat was seen as a consequence of their own moral backsliding and not of the superior military strength of the enemy.

Heike Behrend’s account of the internal organization of the Holy Spirit Movement is welcome, as there are very few such accounts in the literature. The organization of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, the military wing of the movement, was complex. Beneath the overall authority of Lakwena, entitled ‘Chairman and Commander in Chief, there were many levels of command and much use of written regulations such as the Holy Spirit Safety Precautions and the Holy Spirit Tactics. Many Acholi men had military experience, the older ones as members of the King’s African Rifles during the Second World War and the younger majority as either members or foes of the various armed forces that had been raised by Obote and Idi Amin and had engaged in civil wars throughout much of the postcolonial period. They knew how to organize a modern and literate army. But there was more to it than the merely military aspect. The organization of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces provided a coherent structure in an incoherent situation, and created order within disorder. The emphasis on controlling witchcraft, the rules against taking food or women by force, of giving written receipts for ‘donations’, and the other regulations, were all part of constructing order. As Behrend states, to draw up and date documents provided proof that the transactions had actually taken place: they constructed history. These rules served to form a new community and gave a new and common identity to people of many descents and ethnic groups – Acholi, Lango, Teso and others. Their joining together validated Alice’s claim to the leadership of all Uganda.

Besides their own leaders and troops, the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces had other allies in the form of the denizens of ‘nature’ and the environment. These appeared during the semi-mythical ‘journey to Paraa’ (a traditional spiritual centre) in May 1985, when Alice’s prophetic powers began to take shape. She claimed to have persuaded many animals and natural phenomena to become allies; and in later battles her soldiers were aided by 140,000 spirits, bees, snakes, rivers, rocks and mountains. The link with nature meant more than merely extending Alice’s authority beyond the human and social. It implied that Lakwena gave animals, bees and rocks speech and the power to communicate with one another, that the horrors perpetrated by the Ugandan government and its army affected not only the Acholi but also insulted and destroyed the environment in which they lived, and that Lakwena and his adherents were fit to lead and control the entire world.

All this actually happened only a few years ago. We are grateful to Heike Behrend for presenting the history of Alice and her Holy Spirit Movement so lucidly and movingly.