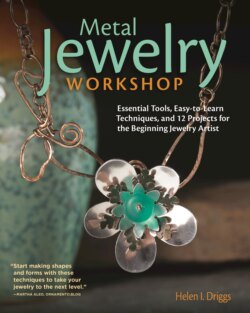

Читать книгу Metal Jewelry Workshop - Helen I. Driggs - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Tools of the trade

ОглавлениеThere are hundreds of specialty hand tools and other types of equipment used in the jewelry arts. Usually, a career craftsperson will build their tool and equipment inventory slowly and steadily over time, as space, need, and resources allow. One of the best ways to ensure that a potential tool purchase is appropriate is to estimate the amount of time and effort that particular tool will save. Justify a tool purchase carefully, considering the use you will get from a tool before buying it. If and when you do buy, choose the highest-quality tool your budget will allow, particularly for daily-use hand tools. It is wiser to spend more for a well-made tool at the start than it is to end up purchasing several low-quality models over time, only to abandon and replace them with a quality version in the end. In jewelry making, patience is an essential skill that applies not only to creating work, but also to tool acquisition.

General Hand tool and Technique Categories

In most jewelry workshops, hand tools are typically grouped and stored by the jobs they perform. Arrangement of a jewelry-making workspace is highly individual, and you will find that over time you may reorder, rearrange, sort, separate, change, and expand your work area many times as your skills and interests improve and change. But there are several broad technique categories in jewelry making (and specific tools associated with those processes) that can serve as guidelines for ordering your workspace. It is a good idea to keep these categories and your needs and preferences in mind as you add tools and equipment to your workshop. The four categories below, in fact, are reflected in the structure of Part 2 of this book.

Metal preparation techniques include layout, marking, measuring, weighing, and cleaning. Never underestimate the importance of careful measuring, proper marking, and clean metal.

Metal manipulation techniques include gripping, holding, bending, thinning, twisting, forming, texturing, stamping, curling, and coiling. Tools associated with these techniques are among the most abundant and widely varied in the craft of jewelry making.

Metal severing or separation techniques include shearing, sawing, drilling, scribing, cutting, clipping, and punching. This category of tools requires focused attention during use to avoid injury, because many of these tools feature very sharp cutting edges and require great force to use.

Metal abrading and refinement techniques include grinding, filing, sanding, scraping, burnishing, and polishing. Another huge category of tools, this group includes metal-specific products and tools as well as those designed for broad or general use.

GOOD, BETTER, AND BEST

Throughout Part 2 of this book, you’ll discover alternatives for completing a process or technique using different types of tools, including less expensive, budget-friendly options as well as more sophisticated, costly specialty tools appropriate to a semipro to pro workshop. Watch for the Good, Better, and Best box as you read to learn other methods of getting a job done and for ideas and tips when you are ready to add new tools to your jewelry-making space.

Workshop Safety

Making jewelry with hand tools is typically not dangerous; however, it is important to keep safety in mind when using any tool—no matter what you are doing. Remember, metal can be sharp, hammers can bruise, pliers can pinch, and cutters can cut. Always be mindful in the workshop, move slowly and steadily, and think every process through before attempting it with tools and metal. Look at your hands as you work, turn off your phone, work under good lighting, and proceed carefully and methodically.

Here are the five commonsense, non-negotiable rules every student working in my shop must follow. I learned them by following my own teacher’s rules, and you will most likely adopt them in your own workspace and eventually pass them on, as well.

1. Wear safety goggles whenever you manipulate, sever, separate, and abrade metal. Your eyes are one of your most valuable (and vulnerable) tools, so take the time to protect them.

2. Keep a first aid kit with antiseptic solution, bandages, and antibacterial ointment handy, as you’ll appreciate it when the inevitable scrape or cut occurs. If you do get hurt, always take a short break away from the workshop before starting again to regain your composure. Even little injuries that you think are no big deal can throw off your concentration without you realizing it.

3. Dress appropriately in the workshop. Tie back hair, remove all jewelry, and wear fitted clothing to prevent snags, tangles, trips, or falls. Closed-toe shoes will protect your feet in the event of flying metal or falling tools.

4. Be awake and alert when making jewelry to avoid costly or potentially hazardous mistakes. I will usually not begin a difficult process at the end of the workday, but instead save it for the next morning when my mind is fresh.

5. Read the instructions thoroughly before you start. If unsure, reread them until you completely understand what to do. When in doubt, stop. Your safety matters more than any jewelry object, so don’t proceed until you are confident that you are certain of what to do.

The Jeweler’s Dozen

Well-made jewelry tools can be seductive and intriguing objects of beauty. As you are learning, it can be daunting to know which tools you truly need, so it’s tempting to enthusiastically purchase tools you think you might need—even if you don’t know how they work! Because of this, every jewelry maker ends up with a stash of beautiful and supremely cool but seldom-used tools. If you enjoy making jewelry, this will inevitably happen to you, too.

That said, no matter what level of experience a jewelry maker may have, there are about a dozen essential hand tools common to all jewelers everywhere. This “jeweler’s dozen” is made up of daily-use hand tools that you will reach for every time you create jewelry. Choose this group of tools wisely and learn to use them well to get the most enjoyment from your work over the long term. After this brief introduction to the jeweler’s dozen tool kit, you will learn more about each tool in depth in Part 2. By following the techniques and practicing the exercises in Part 2, you will learn how to use all of the tools correctly.

TOOL 1: B+S GAUGE

A Brown and Sharpe (B+S) gauge determines the thickness of sheet metal and wire. Two metal measurement systems exist—American Standard and British Standard—so it is important to choose a gauge appropriate to your region. B+S gauges are marked with the metal gauge size on one side and the equivalent decimal measure on the reverse. Well-made measuring tools are expensive, but will have tolerances down to less than one one-hundredth of a millimeter. Inexpensive pocket metal gauges are available, and this type is often acceptable for most beginner-level work. In lieu of a B+S gauge or other metal gauge, a millimeter ruler used with magnification can help to determine gauge, although for thin materials, accuracy will be very difficult to achieve.

TOOL 2: MILLIMETER RULER

As a rule, most jewelry or jewelry-making components and parts are usually very small. Many jewelry materials and supplies are denoted and sold using the metric system. It is possible to purchase sheet metal by the inch or foot; however, other supplies like milled metal stock, gemstones, beads, manufactured components, and even tools are typically denoted using the metric system of measurement. A hardened steel millimeter rule that also indicates inches will provide the best of both worlds. Choose a 6" (15cm) model, which will usually suffice for most sheet metal measurement in jewelry scale.

TOOL 3: RING CLAMP

One of the unsung heroes of the jewelry-making workshop, the leather-lined jaws of a ring clamp will help you hold very tiny things during drilling, filing, sawing, sanding, forming, and polishing. Most models feature a round side for rings and a straight side for other shapes. Brace the ring clamp against or in the V slot of the bench pin to support the metal as you work. Always choose wood over plastic, because a wood clamp can be easily modified for specialty work. In a pinch, a large, sturdy wooden clothespin and a small strip of leather can substitute for a proper ring clamp.

TOOL 4: BASIC UTILITY PLIERS

A tool is super handy when it’s essentially three tools instead of just one! Before getting into details, first think of pliers as strong, miniature metal hands that can be used for holding tiny things as well as for forming or shaping them. There are literally hundreds of kinds of pliers available on the market, but the three you’ll use most in jewelry work are non-serrated round-nosed, chain-nosed, and flat-nosed pliers. Look at pliers with the jaws aimed toward your face to figure out what they are for. For all pliers, it is good to note that the shorter the jaws are, the stronger the grip will be. You can economize on pliers at a hardware store, but know that the more expensive and quality jewelry-specific pliers will be more hand-friendly, are able to bend thicker metals without twisting out of shape, and will become some of your most-used tools.

Round-nosed pliers (middle) have jaws shaped just like you would think—round. They’re used for making curved or circular shapes, or for holding those kinds of shapes.

Chain-nosed pliers (left) look like two shallow D shapes, with the flat bar of each D touching in the center. Engineered for chain making, these sturdy pliers will get into tight places and allow you to close findings, pinch sheet, and move metal with ease.

Flat-nosed pliers (right) make straight-sided bends in metal. If you need zigzag, square, or triangular bends in a wire or strip of sheet, these are the pliers to reach for.

TOOL 5: UTILITY HAMMER

To most jewelry artists, hammer plus metal equals a perfect match. Hammers for jewelry work come in two classes: those designed for striking jewelry metal, and those designed for striking tools. Utility hammers fall into the latter class. These all-purpose hammers include classic ball peen (or pein) hammers you’ll find at most hardware stores, as well as chasing hammers, specific to the jewelry trade. A chasing hammer is designed to strike punches or other tools during the art of chasing—a metalsmithing technique that produces different levels, designs, and shapes in sheet metal by stretching and forming it without the use of cutting or soldering. You can also use utility hammers to texture or flatten the edges or surface of sheet metal and wire.

TOOL 6: STEEL BLOCK OR ANVIL

One of the best properties of metal is that it is malleable. Malleability means that something can be textured, stretched, twisted, and bent without breaking. For example, when you strike soft metal with a hammer, it will dent. Some metals are so soft that a punch or chisel can perforate them. Having a simple block of hard steel or a small anvil on hand will prevent metal from stretching, cupping, or denting when it is struck with a hammer or other steel tool. Many alternatives to a jewelry-quality steel block exist: recycled railroad rails, old engine parts, and discarded steel can often be found in scrap yards, although it may be rusted or distressed. Flea markets and machine shops are also a good option for hunting down useful small strips of old tool steel as a substitute for an anvil. Another option is a steel vise with a large, flat work surface.

TOOL 7: CENTER PUNCH

The pointed end of a center punch can be used decoratively for creating all-over dotted patterns, as well as for marking and utility work during the creation process. To use the punch for marking the position of a hole to be drilled, position the pointed end of the tool at the center position where a hole is to be drilled and gently strike the flat end with a utility hammer. It is never necessary to strike too hard; just a small dent, or divot, in the metal will effectively guide a rapidly spinning drill bit and prevent it from bending or breaking. A serviceable substitute for a center punch is a sharpened, non-galvanized, heavyweight, 4" (10cm) finishing nail.

Utility hammers

Bench pins

TOOL 8: JEWELER’S SAW AND BLADES

The jeweler’s saw is probably the most important hand tool to master in jewelry making. Sawing and saw piercing are basic operations for most metal work. Saw frames come in many depths, shapes, and price ranges. A good starting point is the classic university-quality 4" (10cm) German saw frame with a wooden handle available from nearly every jewelry supply source. General-purpose saw blade sizes come in a variety of sizes to suit your needs. There is no substitute for a quality jeweler’s saw; purchase the best you can afford.

TOOL 9: BENCH PIN

Jewelers typically work at a specially designed bench that is higher than an ordinary worktable, measuring about 37" (94cm) from floor to worktop. The jeweler’s bench is fitted with a bench pin, which is a small flat or wedge-shaped piece of wood that is mounted facing the jeweler like a miniature diving board and which is where all of the precision work like sawing, filing, and other techniques happen. Portable bench pins are designed to clamp onto almost any worktable up to about 2" (5cm) thick. In lieu of a dedicated bench pin, a simple block of 1" x 3" (2.5 x 7.5cm) pine can be clamped to the worktop with a C-clamp, but it is essential to cut a “V” slot in the wood for successful use of the jeweler’s saw.

TOOL 10: METAL SHEARS AND WIRE CUTTERS

Wire cutters and metal shears can be hazardous because sharp edges are produced with this type of cutting tool and great force is applied as you snip, so sharp bits of metal can fly off and become dangerous airborne weapons. Always wear safety goggles when using them! Keep fingers well away from the blades of any cutter as you are using it to prevent injury. There are several types of cutters with different blade styles and cutting actions: straight, side, angle, flush, and semi-flush cutters all work by compressing metal and severing it at the blade. Compressed edges and V-shaped ridges are produced when metal is cut with this class of tool, and they must later be abraded away. Hardware store wire cutters are typically fine for cutting most jewelry wire and thin metals.

TOOL 11: HOLE PUNCH, HAND DRILL, OR ROTARY TOOL

The ability to drill or punch holes in sheet metal allows for complex saw-piercing, as well as the creation of interior openings, holes for rivets and jump rings, and decorative effects. Simple hole punching pliers or a hand drill and drill bits are an essential in every jewelry workshop—with the option to upgrade to an electric rotary tool as soon as possible. Hand drills and small drill bits can be found in most well-stocked hardware stores. Always drill slowly with the sheet metal positioned over a block of wood to prevent dulling or breaking the drill bit.

Basic hand files

TOOL 12: BASIC HAND FILES

A large, coarse-to-medium file is great for cleaning up metal edges, removing sharp metal burrs from sawn sheet and punched holes, making joins flat, and cleaning up scratches and scrapes. When filing, always use the largest file you can to get the job done. It is important to remember that file teeth will only cut on the forward stroke—that is, away from the file handle, or tang. The first file that should be purchased is a medium-coarse #2-cut half-round or flat hand file, measuring about 8" (20cm) long. Needle files are a good next choice, but are designed for smaller work. Economize on files at the hardware or discount store, but be sure to purchase files designed for metal, not for woodworking.

Metal shears and wire cutters