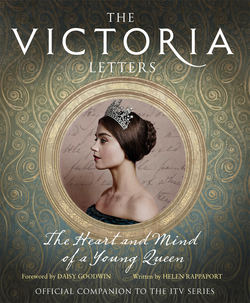

Читать книгу The Victoria Letters: The official companion to the ITV Victoria series - Хелен Раппапорт - Страница 11

ОглавлениеLITTLE DRINA

‘It was a rather melancholy childhood’

– Victoria –

ON 28 APRIL 1819 A RAGGLE-TAGGLE CONVOY of 20 carriages, thick with the dust and grime of 30 days on bumpy roads from Amorbach in Bavaria, rattled up the drive of London’s Kensington Palace. The journey its exhausted occupants had just completed – along with a mountain of luggage, two Russian lapdogs and a cage of singing birds – had been a frenetic race against time to ensure that the first legitimate heir to the British throne to be produced by any of George III’s sons be born in England.

The soon-to-be parents were Edward, Duke of Kent – the fourth of the nine sons of George III – and his wife, Marie Louise Victoire, formerly a princess of the German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. They had until now been living at Amorbach in greatly straitened circumstances – thanks to an accumulation of debts brought on by the Duke’s compulsive overspending from the moment he completed his military training.

Their one hope of a change in fortunes had followed the death of Princess Charlotte of Wales (the Duke’s niece and Duchess’s sister-in-law), who had died tragically in 1817. If the Duke outlived his elder, childless brothers, he would become King. And the child his wife was soon to bear, the one most likely to outlive them all, would be fifth in line to the British throne.

BY 1819, THE DUKE OF KENT WAS 50. Determined to marry and beget an heir, the previous year he’d discarded his long-term French mistress, Madame St Laurent – giving her a pension for going without making a fuss – and set about finding a wife. As a son of King George III, he knew that his marriage to Victoire of Saxe-Coburg was far from ideal. She was considerably inferior in royal dynastic terms and was a widow with two children. But the Duke needed to legitimise his claim to the throne in the eyes of the public by marrying and becoming a respectable family man.

Announcement of the Royal birth in The London Gazette.

Despite the draining 427-mile journey from the Continent, at 4.15 a.m. on 24 May, the Duchess of Kent, who seemed to have suffered no adverse effects, gave birth to a pretty, fair and fat baby girl. She was very like her father, having the unmistakably large blue eyes of the Hanoverians. The birth prompted the entire British nation to heave a sigh of relief, for it came during one of the old King George III’s bouts of madness and the Regency of his eldest, unpopular son George.

‘Fair and fat’ – baby Victoria.

Script quote:

Duchess of Kent:

Driving in a coach from Amorbach, across France, so that you could be born in England – I was so worried that you would come early and your wicked uncles would say you were not English.

THE DUCHESS OF KENT HAD RESISTED the services of a male physician to deliver her child and had instead brought with her the family’s own German obstetrician, Marianne Siebold – one of the first women in Europe to obtain a medical degree. Siebold announced the birth to the dignitaries who had gathered in an ante-room to bear witness to the legitimacy of the birth, among them the Duke of Wellington. ‘Boy or girl?’ he asked her.

‘Girl,’ answered the doctor, then added in her thick German accent, ‘Ver nice beebee. No big, but full. You know, leetle bone, moosh fat.’

Just three months later, Marianne Siebold would deliver another baby, at the Castle Rosenau near Coburg – the son of the Duchess of Kent’s brother, Duke Ernest of Saxe-Coburg, and a cousin to the little Princess. From the outset, the grandmother of the two infants, the dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, was determined that her dear grandson Albert and her adored new granddaughter should one day marry. From her home in Ebersdorf she wrote adoringly of little baby Albert. ‘What a charming pendant he would be to the pretty cousin,’ she remarked, setting the matchmaking wheels in motion.

Young Prince Albert, Victoria’s cousin and young suitor.

Feature:

PRINCESS CHARLOTTE

‘She might have been saved if she had not been so much weakened’

– Victoria –

CHARLOTTE (BORN 1796), only child of George, Prince Regent by his wife Caroline of Brunswick, was until her death George III’s only legitimate grandchild. Warm-hearted and engagingly impulsive, she was under pressure to secure an advantageous dynastic union through marriage to Prince William of Orange. She was desperate to find an alternative, and after meeting Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, pleaded with her father to be allowed to marry him instead. Alexander I of Russia saved the situation by offering his sister Anna to the Prince of Orange, and the Prince Regent allowed Charlotte and Leopold to be married in 1816. It seemed a happy union and was popular with the British public, who were overjoyed at the news of their much-loved princess’s pregnancy in 1817.

Charlotte, though robust and healthy, was put on a strict diet and bled mercilessly during pregnancy. After an agonising, protracted two days of labour, made worse by incompetent doctors, on 5 November 1817 she gave birth to a stillborn son but shortly afterwards suffered a haemorrhage, and died of shock and exhaustion. Her death provoked unprecedented public grief: regarded as a national disaster, the simultaneous deaths of two heirs to the British throne presented a potential crisis in the monarchy. There was now a race to see who, among George III’s surviving sons, could produce a legitimate heir to replace Charlotte. Adelaide, wife of the Duke of Clarence (the future William IV), hoped to give birth to an heir, but between 1819 and 1822 lost all four of her babies.

Having lost his wife and child, Leopold made it his life’s mission to prepare Victoria for the throne that Charlotte should have occupied.

VICTORIA’S DELIGHTED FATHER PRONOUNCED his new baby daughter ‘as plump as a partridge’ and was ridiculously proud and protective of her.

‘Don’t drop her! Don’t drop her! You might spoil a queen!’ he had told the Bishop of Salisbury when he visited soon after and took the baby awkwardly in his arms. Mindful of his daughter’s royal prospects, the Duke announced that he wished her to be named Elizabeth after the great Tudor monarch, but at her christening the Prince Regent instead chose the name Alexandrina, after the baby’s godparent Tsar Alexander I of Russia, who had recently been Britain’s ally in the war against Napoleon. Then, after some prevarication, and with everyone gathered expectantly around the font, he allowed a second name, Victoire, after her mother. Fondly nicknamed Mai-blühme, or May Blossom, by her German mother and grandmother throughout her early childhood, the princess who would become Queen in 1837 was generally known as Drina.

The first happy months of Drina’s life were, however, brought to a sudden end when, in January 1820 while staying by the sea at Sidmouth in Devon, her father caught a chill and died of pneumonia. His last words were to beg God to protect his wife and child.

Although she would never have more than the most distant recall of her father, Victoria later remarked, ‘I was always taught to consider myself a soldier’s child.’ She nursed a somewhat rosy view of her father’s long and not altogether distinguished military career, which was to give her a lifelong admiration for the army. But she missed his presence and throughout her life, as if to compensate, she would latch on to a succession of strong father figures.

Six days after the Duke’s death, his father King George III also died. In less than a week little baby Drina was propelled a great deal closer to the throne.

The Duke of Kent, Victoria’s father and fourth son of George III.

Kensington Palace, Victoria’s childhood home.

Feature:

KENSINGTON PALACE

‘My dear old home’

– Victoria –

THE ORIGINAL KENSINGTON PALACE, built on the western edge of Hyde Park in 1661, was a red-brick Jacobean mansion situated in what was then a beautiful, tranquil park of chestnut and beech trees. It was bought by the royal family in 1689 for King William III, because the damp riverside palace at Whitehall had aggravated his asthma. During William’s reign the interior of the house underwent extensive renovations designed by the architect Sir Christopher Wren. Queen Anne loved it so much that in 1704 she added a grand orangery, and George I ordered its beautiful gardens to be laid out in 1723–27 by the landscape gardener William Kent.

Little money, however, was spent on maintaining the exterior fabric of the building and it fell into disuse as a royal residence after the death there of George II in 1760. Once Buckingham House (later Palace) was built in central London, George III preferred to live there and Kensington instead became a home for minor royals. The Duke of Kent had been allocated two floors of apartments in 1798, which he furnished, at considerable expense, with new upholstery, curtains and bed hangings. The new furnishings, however, did little to enhance the dark and gloomy interior, which had long been infested with black beetles and other insects, and the Duke’s mounting debts drove him to seek refuge abroad.

By the time Victoria was born, Kensington Palace’s only remaining occupant was her rather frightening and eccentric Uncle Sussex. She later recalled:

My earliest recollections are connected with Kensington Palace, where I can remember crawling on a yellow carpet spread out for that purpose – and being told that if I cried and was naughty my Uncle Sussex would hear me and punish me, for which reason I always screamed when I saw him!

VICTORIA’S REMINISCENCES OF HER EARLY CHILDHOOD, WRITTEN IN 1872

Uncle William and Aunt Adelaide send their love to dear little Victoria with their best wishes on her birthday, and hope that she will now become a very good Girl, being now three years old. Uncle William and Aunt Adelaide also beg little Victoria to give dear Mamma and to dear Sissi a kiss in their name, and to Aunt Augusta, Aunt Mary and Aunt Sophia too, and also to the big Doll. Uncle William and Aunt Adelaide are very sorry to be absent on that day and not to see their dear, dear little Victoria, as they are sure she will be very good and obedient to dear Mamma on that day, and on many, many others. They also hope that dear little Victoria will not forget them and know them again when Uncle and Aunt return.

LETTER FROM THE DUCHESS OF CLARENCE TO VICTORIA, 24 MAY 1822

My dearest Uncle – I wish you many happy returns on your birthday; I very often think of you, and I hope to see you soon again, for I am very fond of you. I see my Aunt Sophia often, who looks very well, and is very well. I use every day your pretty soup-basin. Is it very warm in Italy? It is so mild here, that I go out every day. Mama is tolerable well and am quite well. Your affectionate Niece, Victoria.

P.S. I am very angry with you, Uncle, for you have never written to me once since you went, and that is a long while.

LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, 25 NOVEMBER 1828

FOR THE MOST PART, life at Kensington Palace was unremittingly quiet and uneventful for the young Victoria:

We lived in a very simple, plain manner; breakfast was at half-past eight, luncheon at half-past one, dinner at seven – to which I came generally (when it was no regular large dinner party) – eating my bread and milk out of a small silver basin. Tea was only allowed as a great treat in later years.

~ VICTORIA’S REMINISCENCES OF HER EARLY CHILDHOOD, WRITTEN IN 1872

The Duchess, seeking to protect her precious daughter at Kensington from the pernicious influence of court and her predatory Hanoverian uncles, installed little Drina’s chintz-curtained bed on one side of her own. ‘I was brought up very simply, never had a room to myself till I was nearly grown up and always slept in my Mother’s room till I came to the throne,’ Victoria later wrote.

On the other side of the Duchess’s bed slept Feodora, her daughter from her previous marriage. With playmates very few and strictly vetted, Drina clung to her adored half-sister. Feodora cosseted her and would often take her into her own bed in the mornings; she liked nothing better than pulling her baby sister along in a hand-carriage in the gardens outside. But with the emphasis so much on Drina, Feodora remained a shadowy figure, a ‘timid onlooker’, as she herself said, of the life of her far more important half-sister.

Victoria adored her: ‘My dearest sister was friend, sister, companion, all to me, we agreed so well together in all our feelings and amusements,’ she later wrote. It hurt her that so little attention was paid to dearest Fidi, as she called her. ‘Why do all the gentlemen raise their hats to me, and not to Feodora?’ she once asked.

Script quote:

Mrs Jenkins:

Funny to think she’s never slept a night alone or even walked down the stairs without her hand needing holding and now she is Queen.

Character Feature:

DUCHESS OF KENT

- Victoria’s Mother -

‘Like having an enemy in the house’

– Victoria –

THE DUCHESS OF KENT WAS born Marie Louise Victoire, daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and his wife Augusta in 1786. She was the sister of Leopold, King of the Belgians, and Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg Gotha – Prince Albert’s father. At the age of seventeen she was married to the Prince of Leiningen, a man 23 years her senior, and had two children by him, Charles in 1804 and Feodora in 1807. Widowed in 1814, she was steered in the direction of the unmarried Duke of Kent by her ambitious brother Leopold, who knew that the Duke was keen to father a legitimate heir to the British throne. Although on paper it was an advantageous royal match for a relatively lowly Saxe-Coburg, the Duchess’s brief life with the Duke was plagued by financial insecurity and an endless and repeated flight around Europe from their creditors. When the Duke died unexpectedly in 1820, Victoire was left penniless and socially isolated until Leopold, with his eye on the prize of his niece’s accession to the throne, bailed her out with an annuity.

Alienated from the court and King William, who disliked her intensely, the Duchess immured herself and her daughter at Kensington Palace. Her vulnerability, isolated and friendless as she was, laid her open to the domineering influence of the controller of her household, Sir John Conroy, who brought out the worst in her by encouraging her ambitions to become Regent. Aware of this and infuriated by the Duchess’s constant demands over precedence, William willed himself to stay alive until his niece Victoria had reached her eighteenth birthday in May 1837.

Once upon the throne, Victoria ruthlessly relegated her mother to a separate suite of rooms and it was only later, thanks to Prince Albert, that mother and daughter were reconciled.

Catherine H. Flemming Plays the Duchess:

‘With all the political manoeuvring around the young Victoria, her mother didn’t want her to choose the wrong path. Conroy was guiding [the Duchess] and he was the only one she trusted. The Duchess stayed at court even though she was a complete lone wolf. She was never able to step into the bubble of the English royals. She was always someone on the side watching, as a spy, in order to protect her daughter.’

ONCE DRINA REACHED THE AGE OF FOUR, a carefully monitored regime, which became known as the ‘Kensington System’, was devised for her by the Duchess, on advice from the controller of her household, Sir John Conroy. Conroy had previously served as the Duke of Kent’s equerry and since his death had gained a considerable hold over the Duchess and her financial affairs. This system of concerted isolation of the young and impressionable child – and which Drina’s governess, Fräulein Louise Lehzen, assisted – was designed to exclude any outside influences that might dilute the little girl’s undivided loyalty to her mother and undermine her mother’s ambitions for Drina’s ascent to the throne and her own regency should this happen before she was eighteen. It was important to Conroy and the Duchess to control Drina’s dependence on them and resist any attempts by the King to insist that she, as heir to the throne, live with him at court. But in so doing, they turned a little girl’s love into resentment and ultimately hatred.

A daily register of Drina’s upbringing was meticulously recorded. After breakfast she would take exercise in the garden, often riding on her donkey or in a small pony cart until ten. For the next two hours her mother instructed her, assisted by Lehzen (who had originally been Feodora’s governess and was appointed subgoverness to Drina in 1824). ‘Dear Boppy’ – Mrs Brock, her nurse – provided more plain food for lunch at two, followed by lessons until four, after which Drina went outside again for exercise. Another very plain meal of bread and milk came at seven. Promptly at 9 p.m. she was tucked up in the bed next to her mother’s. At all times the child was watched, cosseted and protected from potential harm. She was not even allowed to go up and down stairs without an adult holding her hand.

A young Victoria.

When little Drina’s regular education began, her mother warned her tutor, the Revd. George Davys, ‘I fear you will find my little girl very headstrong, but the ladies of the household will spoil her.’ The Queen herself later freely admitted her early reluctance in the schoolroom, saying that she ‘baffled every attempt to teach me my letters up to five years old – when I consented to learn them by their being written down before me’.

It was Davys’s task to teach Drina her alphabet and elocution, and to try and soften the edges of the pronounced German accent she had assimilated from her mother. Feodora also helped with spelling, including the composition of one of the four-and-a-half-year-old’s first, very forthright, letters – addressed to the Revd. Davys:

MY DEAR SIR, I DO NOT FORGET MY LETTERS NOR WILL I FORGET YOU

~ VICTORIA

Reading was de rigueur – mainly the scriptures and a great deal of devotional literature. Her mother allowed some poetry, but very little fiction. Mr Stewart came over from Westminster School to teach Drina writing and arithmetic; Madame Bourdin arrived twice a week to teach dancing and deportment; Mr Bernard Sale from the Chapel Royal encouraged Drina’s musical talents and her singing; her riding master Mr Fozard ensured that she became a most accomplished horsewoman, while Richard Westall of the Royal Academy nurtured her considerable talent for painting and sketching, and she was also taught French by M. Grandineau and German by the Revd. Henry Barez; Latin and Italian were added later.

Script quote:

Victoria:

There was a time, Mama, when I needed your protection, but instead you allowed Sir John to make you his creature.

MORE IMPORTANTLY PERHAPS in that early training, Drina was taught always to be truthful, punctual and frugal and to take plenty of fresh air and exercise. She went out into Kensington Gardens in all weathers, sometimes on Dickey, her favourite white donkey. Dickey – a present from the Duke of York – its head decorated with blue ribbons, was led by an old soldier who had once served her father. Whenever the little princess emerged from the Palace, often holding hands with Feodora, she was friendly to everyone she met, bidding them ‘Good morning’ with a smile.

By the age of eleven she seemed exceptionally accomplished and forward for her age. ‘A child of great feeling,’ thought the Revd. Davys. She was impulsive and generous – but she could also be wilful, and, as the Behaviour Books recording her every misdemeanour noted, on one occasion she had been ‘very very very horribly naughty’.

Queen Victoria later explained that ‘I was naturally very passionate, but always most contrite afterwards’. She may have been stubborn and impetuous but an abiding quality, from a young age, was her truthfulness, reflected in the often surprisingly candid comments in her journal.

High days and holidays in the protected life of young Drina during the 1820s amounted to summer breaks at Ramsgate and other seaside towns, where she rode her donkey on the sands and was sometimes allowed to play with children of the gentry. Other than this, visits to her mother’s brother, Uncle Leopold, were the thing she most longed for. ‘Claremont remains as the brightest epoch of my otherwise rather melancholy childhood,’ the Queen later wrote, and she and Feodora would often stay at this Palladian mansion near Esher in Surrey for weeks or months at a time, taking great delight in playing in its huge parkland and gardens.

Princess Victoria in Kensington Gardens.

Twenty years later her sister recalled in a letter how much the two sisters had loved Claremont in comparison to Kensington Palace – to which they always returned with heavy hearts:

When I look back upon those years, which ought to have been the happiest in my life, from fourteen to twenty, I cannot help pitying myself. Not to have enjoyed the pleasures of youth is nothing, but to have been deprived of all intercourse, and not one cheerful thought in that dismal existence of ours, was very hard. My only happy time was going or driving out with you and Lehzen; then I could speak and look as I liked.

~ LETTER FROM FEODORA, 1843

During this difficult time, Drina’s German grandmother, Augusta of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, continued to dote on and adore her little May Blossom from a distance. In 1825 the 68-year-old visited for two months. It was a moment that little Drina had longed for:

I recollect the excitement and anxiety I was in, at this event, going down the great flight of steps to meet her when she got out of the carriage, and hearing her say, when she sat down in her room, and fixed her fine clear blue eyes on her little grand-daughter whom she called in her letters: ‘The flower of May’, ‘Ein schönes Kind’ – ‘a fine child’.

~ VICTORIA’S REMINISCENCES OF HER EARLY CHILDHOOD, WRITTEN IN 1872

Princess Augusta, Victoria’s grandmother.

Script quote:

Victoria:

When I was growing up, Mama and Sir John – they kept me under constant supervision. I was allowed no friends, no society, no life of my own.

She was a good deal bent and walked with a stick, and frequently with her hands on her back. She took long drives in an open carriage and I was frequently sent out with her, which I am sorry to confess I did not like, as, like most children of that age, I preferred running about. She was excessively kind to children, but could not bear naughty ones, and I shall never forget her coming into the room when I had been crying and naughty at my lessons – from the next room but one, where she had been with Mamma – and scolding me severely, which had a very salutary effect.

VICTORIA’S REMINISCENCES OF HER EARLY CHILDHOOD, WRITTEN IN 1872

AUGUSTA WAS BESOTTED WITH her beloved granddaughter, enthusing about her in letters home and proclaiming her to be ‘incredibly precocious for her age’. She had never seen ‘a more alert and forthcoming child’.

Little Mouse is charming: her face is just like her father’s, the same artful blue eyes, the same roguish expression when she laughs. She is big and strong as good health itself, friendly and cuddlesome – I would even say obliging – agile, poised, graceful in all her movements. […] When I speak incorrectly, she says quite softly, ‘Grandmama must say …’ and then tells me how it should be said. Such natural politeness and attentiveness as that child shows has never come my way before.

~ LETTER FROM AUGUSTA, 6 AUGUST 1825

Augusta did, however, worry that Drina ‘eats a little too much, and almost always a little too fast’, and noted that she was also rather short for her age. But she was already displaying other far more important qualities. Grandmama Augusta was one of the first to observe an enduring trait of the future Queen: ‘when she enters a room, and greets you by inclining her head, according to the English custom, there is staggering majesty’.

In February 1828 came a terrible wrench for Drina when Feodora, now aged eighteen, left England to marry Ernst, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg – a man much older than herself, whom she hardly knew. From her new home she wrote endless letters to her half-sister in England, filled with love and sorrow at their separation.

If I had wings and could fly like a bird, I should fly in at your window like the little robin to-day, and wish you many very happy returns of the 24th, and tell you how I love you, dearest sister, and how often I think of you and long to see you. I think if I were once with you again I could not leave you so soon. I should wish to stay with you, and what would poor Ernst say if I were to leave him so long? He would perhaps try to fly after me, but I fear he would not get far; he is rather tall and heavy for flying. So you see I have nothing left to do but to write to you, and wish you in this way all possible happiness and joy for this and many, many years to come. I hope you will spend a very merry birthday. How I wish to be with you, dearest Victoire, on that day!

LETTER FROM FEODORA TO VICTORIA, MAY 1829

George I, first Hanoverian king.

Feature:

THE HANOVERIANS

‘I am far more proud of my Stuart than of my Hanoverian ancestors’

– Victoria –

BY BECOMING QUEEN, Victoria ended an uninterrupted line of Hanoverian kings from 1714 when George I, Elector of Hanover, assumed the British throne after Queen Anne died childless. To have a young, virginal queen on the throne after a long line of disreputable males was a refreshing change: the Hanoverians had not endeared themselves to the British public. Collectively the four Georges and William preceding Victoria were looked upon, along with their mistresses and scores of illegitimate children, as rogues, blackguards and fools from a petty provincial German kingdom. The public baulked at having to support the vast entourage of dependents (including two mistresses) accompanying George I to England.

His son, George II, provoked a deep, abiding hatred in the Scots when he ordered the brutal suppression of the Jacobite Rebellion (1745–46).

George III’s tumultuous 60-year reign was punctuated by scandal, political disaster and madness. A devoted husband and father at home, producing fifteen children with his long-suffering wife Caroline, George lost the American colonies in 1783 and quarrelled endlessly with his heir, who assumed the Regency in 1811 upon George’s last, most crippling descent into madness.

George IV, a man of considerable aesthetic taste and a patron of the arts, was nevertheless a lazy spendthrift who abandoned his wife Caroline of Brunswick and squandered a fortune on his lavish coronation. Despite lingering gossip about the ‘bad blood’ of the Hanoverians, Drina had taken a liking to her ‘Uncle King’, as she referred to George IV on a visit to Windsor (1826), remembering him as ‘large and gouty but with a wonderful dignity and charm of manner’. ‘Give me your little paw,’ he said, lifting her into his carriage – a jaunt that had greatly pleased the young princess.

In contrast, she found the last Hanoverian king, her uncle William IV, ‘very odd and singular’, but appreciated his kindness and determination that she be properly prepared for a monarch’s onerous duties. Although the new Queen’s reign would depart dramatically from the path laid by her royal predecessors, Victoria would carry one heritage with her: the slightly bulging blue eyes, round face prone to chubbiness and receding chin were all inherited by her children – unmistakable markers of Victoria’s Hanoverian line of descent.

AS THE 1820S PROCEEDED, Little Drina’s own path to the throne became ever more inevitable. Her uncle, the Duke of York, died in 1827, and in June 1830 King George IV died, making Drina now heir presumptive to the throne after her uncle, the new king William IV. It provided Grandmama Augusta with a moment’s pause for thought:

God bless old England, where my beloved children live, and where the sweet blossom of May may one day reign! May God yet, for many years, keep the weight of a crown from her young head, and let the intelligent, clever child grow up to girlhood before this dangerous grandeur devolves upon her!

~ LETTER FROM AUGUSTA TO THE DUCHESS OF KENT, MAY 1830

In the seven years that followed, Little Drina proved to be more than equal to the challenge that lay before her.