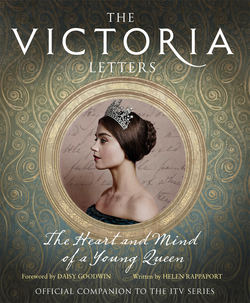

Читать книгу The Victoria Letters: The official companion to the ITV Victoria series - Хелен Раппапорт - Страница 12

ОглавлениеFROM KENSINGTON PALACE TO BUCKINGHAM PALACE

‘She evinces much talent in whatever she undertakes’

– Duchess of Kent –

WHEN PRINCESS VICTORIA was eleven, by now a rather more diligent and conscientious pupil, she is said to have finally discovered that she was in direct line to the throne. Leafing through the pages of a court almanac with her governess Lehzen, she came across a genealogical table of the British succession. Lehzen, writing to Victoria many years later, recalled that the Princess had remarked, ‘I never saw that before.’

‘It was not thought necessary you should, Princess,’ I answered. – ‘I see, I am nearer to the Throne, than I thought.’ – ‘So it is, Madam,’ I said. – After some moments the Princess resumed, ‘Now, many a child would boast, but they don’t know the difficulty; there is much splendour, but there is more responsibility!’ The Princess having lifted up the forefinger of Her right hand, while she spoke, gave me that little hand saying, ‘I will be good!’

~ LETTER FROM LEHZEN TO VICTORIA, 2 DECEMBER 1867

BY THE EARLY 1830S, Victoria was being schooled well beyond her years; training fit for the throne that now, in all likelihood, awaited her. Upon learning of her position as heir presumptive, she is said to have told Lehzen, ‘I understand now, why you urged me so much to learn, even Latin.’ She was indeed a good Latin scholar – tackling Virgil and Horace – and a fluent linguist.

Undoubtedly one of Victoria’s greatest joys in the schoolroom came in 1835, when the Irish-Italian bass baritone Luigi Lablache was appointed to give her singing lessons, in so doing nurturing a lifelong love of Italian opera.

She was still very small for her age – which she worried about – and the Duke of Wellington still found her German accent troubling. Some of Victoria’s ‘mangled phrases’ were, he said, ‘particularly unpleasant, coming from the lips of an English princess’. Victoria dissolved into floods of tears when she heard this. Uncle Leopold was also concerned that her love of food was causing her to put on weight. Victoria reassured him, writing from the seaside in 1834: ‘I wish you could come here, for many reasons, but also to be an eye-witness of my extreme prudence in eating, which would astonish you.’

I like Lablache very much, he is such a nice, good-natured, good-humoured man, and a very patient and excellent master, he is so merry too (…) I liked my lesson extremely; I only wish I had one every day instead of one every week.

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 3 MAY 1836

IN PREPARATION FOR his niece’s accession, King William ordered that an English aristocrat, the Duchess of Northumberland, be appointed to work with Lehzen on teaching Victoria court and ceremonial etiquette and training her in deportment and the social graces. But despite this Victoria continued to gravitate ever more to her governess.

Lehzen remained her closest companion, her trusted friend and ally, so much so that Kensington Palace became clearly divided into two camps, with the Duchess and Sir John Conroy in one and Victoria and Lehzen in the other. Although Sir John Conroy’s daughter Victoire was brought occasionally to play with her, Victoria spent much of her time alone with her treasured dolls: wooden ones, paper ones, dolls made of leather and expensive wax dolls sent from Berlin –132 of them in all, carefully organised and listed in her childlike hand in a small copy book. Each doll had its own name, an explanation of which person it represented – if based on a real person – and who made her costume (herself or Baroness Lehzen).

Victoria’s favourites were the plain wooden jointed dolls of 3–9 inches long with ‘small, sharp noses, and bright vermilion cheeks’ that would fit in her dolls’ house. She based their costumes on those of real-life actors, opera singers and ballet dancers she admired, sewing tiny ruffles ‘with fairy stitches’ and making ‘wee pockets on aprons embroidered with red silk initials’. The dolls were fitted onto a long board full of pegs by their feet so that Victoria could position them and rehearse court receptions, drawing rooms and levées with them.

When she reached the age of fourteen she packed them all away, but she kept them safely stored in a box even after she came to the throne. Recording one of her first conversations with her future favourite Lord Melbourne, she described how, even then, they ‘spoke of my former great love of dolls’.

Script quote:

Conroy:

Still playing with dolls, Your Majesty?

Duchess:

You must put away such childish things now, Drina. I am afraid that your carefree days are over.

Character Feature:

BARONESS LOUISE LEHZEN

- Victoria’s Governess -

‘Dear Lehzen who has done so much for me’

– Victoria –

LOUISE LEHZEN, ALONG WITH UNCLE LEOPOLD, was one of the guiding presences in Victoria’s early life. One of nine children of a Lutheran pastor, the plain, long-nosed Lehzen had lived in obscurity until the age of 35 when she was appointed governess to the Duchess of Kent’s daughter Feodora and brought to England with the family. In service to Victoria from 1824, she rose from subgoverness to friend and adviser and then to lady of the Bedchamber and effective private secretary during those crucial formative years. George IV rewarded her with the honorary title of Hanoverian baroness in 1827 – a title that rather went to Lehzen’s head. Her overweening manner thereafter antagonised many members of the household, who resented the lowly-born Lehzen’s tyranny. They made cruel jokes about her, among them Lady Flora Hastings, who derided the Baroness’s eccentric habit of sprinkling caraway seeds – specially sent over from Hanover – on all her food.

Lehzen was extremely conscientious, to the point of excess, in her duties as governess. Although she could be overly censorious at times, she was also skilful at managing Victoria’s legendary tantrums. More importantly, she kept the lonely little girl company and amused her between lessons – their favourite pursuit together being the dressing of Victoria’s many dolls.

Daniela Holtz Plays Baroness Lehzen:

‘Lehzen was really Victoria’s only confidante and she never betrayed her, never played power games with her. She understood monarchy and power and when Victoria was Queen, she controlled the people who went to her, to protect her.’

DURING HER EARLY YEARS VICTORIA was offered few diversions from the oppressive life at Kensington Place, beyond occasional summer breaks by the sea at Ramsgate and, in 1830, a long holiday to the spa town of Malvern in Worcestershire. En route, she and the Duchess passed through the Midlands where the streets had thronged with people out to greet her. They stopped briefly to see glass-blowing and coining, and visited a porcelain works in Worcester, but otherwise Victoria was not exposed to the realities of Britain’s industrial heartland. There was also a visit to Norris Castle on the Isle of Wight in 1833, and that same year, on her fourteenth birthday, Victoria enjoyed her first royal ball:

At half past seven we went with Charles, the Duchess of Northumberland, Lady Catherine Jenkinson, Lehzen, Sir George Anson, and Sir John, to a juvenile ball that was given in honour of my birth-day at St. James’s by the King & Queen. We then went into the closet, soon after the doors were opened and the King leading me, went into the ball-room. Madame Bourdin was there as dancing-mistress. Victoire was also there, as well as many other children whom I knew. Dancing began soon after. I danced first with my cousin George Cambridge, then with Prince George Lieven, then with Lord Brook […] We then went to supper. It was half past II. The King leading me again. I sat between the King and Queen. We left supper soon. My health was drunk. I then danced one more quadrille with Lord Paget. I danced in all eight quadrilles. We came home at half past 12. I was very much amused. I was soon in bed and asleep.

~ VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 24 MAY 1833

Victoria’s singing lessons, occasional visits to the opera and ballet, and the long, vigorous horse rides she enjoyed at a gallop, all contributed to the variety of experience she so craved. But nothing was better than the joy of a visit in 1834 from Feodora and in 1835 from Uncle Leopold and her new aunt Louisa. ‘What a happiness it was for me to throw myself in the arms of that dearest of Uncles, who has always been to me like a father, and whom I love so dearly!’ she wrote, noting the pleasure of his company at dinner, in contrast to being ‘immured’ at Kensington: ‘I long sadly for some gaiety,’ she wrote plaintively.

Script quote:

Melbourne:

Lady Portman knew your father, Ma’am.

Lady Portman:

Such a handsome man, Ma’am. And a very good dancer.

Victoria:

Was he? I never knew. That must explain why I love dancing so much

DURING THIS TIME, the British public began taking a growing interest in its young queen-in-waiting; Victoria, they declared, was something of a prodigy. ‘Her powers of attention appear extraordinary for her age, and her memory extremely retentive, which indeed phrenologists would infer from the prominency of her eyes,’ noted one observer. Not only was this gifted young mind receiving the best education, but, thanks to Lehzen’s firm management, Victoria’s volatile temper had also been curbed, for her governess allowed ‘no indulgence of wrong dispositions, but corrects everything like resistance, or a spirit of contradiction, such as all children will indulge if they can’.

Meanwhile, Parliament addressed the urgent question of what should happen if the King died before Victoria reached her majority, and decreed that her mother should become Regent, until completion of Victoria’s eighteenth year, and in recognition of this the Duchess was granted an extra £10,000 a year, for Victoria’s household and education. Although her preposterous demand to be titled ‘Dowager Princess of Wales’ was thrown out, she was duly grateful: ‘This is the first really happy day I have spent since I lost the Duke of Kent,’ she said. She was proud of her daughter’s progress:

She evinces much talent in whatever she undertakes […] The dear girl is extremely fond of music, she already fingers the piano with some skill, and has an excellent voice.

~ DUCHESS OF KENT

With Victoria now established as heir apparent, the Duchess of Kent, eager to acquire as much prestige for her as possible, orchestrated a series of ‘royal progresses’ (as King William rather sarcastically called them) to market the Princess to her adoring and curious public. Building on the isolating Kensington System that they had forced Victoria to endure, these excursions were also intended to do the same for the Duchess and Conroy, who harboured ambitions to be regents until Victoria reached the age of 21. A regency would provide them both with considerable wealth, power and status, something they both craved.

Script quote:

Conroy:

Do you really imagine that you can step from the schoolroom straight to the throne without guidance?

WHEN VICTORIA REACHED thirteen Leopold decided the time was right to prime her for her important future role. She was no longer a little princess, he wrote:

This will make you feel, my dear Love, that you must give your attention more and more to graver matters. By the dispensation of Providence you are destined to fill a most eminent station; to fill it well must now become your study. A good heart and a trusty and honourable character are amongst them of indispensable qualifications for that post.

You will always find in your Uncle that faithful friend which he has proved to you from your earliest infancy, and whenever you feel yourself in want of support or advice, call on him with perfect confidence.

~ LETTER FROM LEOPOLD TO VICTORIA, 22 MAY 1832

In 1834 at the end of another tour, first in Kent round the stately homes at Knole and Penshurst and then to the north to visit York, Belvoir Castle and attend the races at Doncaster, Victoria wrote a warm letter to Uncle Leopold, who in 1832 had finally remarried:

My dearest Uncle – Allow me to write you a few words, to express how thankful I am for the very kind letter you wrote me. It made me, though, very sad to think that all our hopes of seeing you, which we cherished so long, this year, were over. I had so hoped and wished to have seen you again, my beloved Uncle, and to have made dearest Aunt Louisa’s acquaintance. I am delighted to hear that dear Aunt has benefited from the sea air and bathing. We had a very pretty party to Hever Castle yesterday, which perhaps you remember, where Anne Boleyn used to live, before she lost her head. We drove there, and rode home. It was a most beautiful day. We have very good accounts from dear Feodore, who will, by this time, be at Langenburg.

Believe me always, my dearest Uncle, your very affectionate and dutiful Niece, Victoria.

LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, 14 SEPTEMBER 1834

Character Feature:

SIR JOHN CONROY

- Controller of the Duchess’s Household -

‘The monster and demon incarnate’

– Victoria –

SIR JOHN CONROY, BORN IN 1786, was to dominate Princess Victoria’s early life. A handsome Irishman, he was appointed equerry to the Duke of Kent in 1818, and rapidly ingratiated himself with the Duchess after the Duke’s death, taking control of her affairs. King William despised his blatant ambition and referred to him as ‘King John’, for Conroy had long nursed delusions of his own, unproven, royal connections. He spent his life aspiring to elevation into the British aristocracy: promotion to a Knight Commander of the Hanoverian Order by George IV had done little to satisfy those ambitions. With the Duchess under his control, he had a major influence over the creation of the Kensington System that isolated Princess Victoria from any unwanted external influences. Power went to his head and he strutted around Kensington Palace as though it were his own private fiefdom.

Conroy’s manner towards the Duchess was frequently overbearing and at times openly and worryingly seductive. It crossed the bounds of propriety and set tongues wagging, to the point where some even alleged that Victoria was his child and not the Duke’s. There is nothing to support this claim, but Conroy certainly took advantage of the Duchess’s weakness and vulnerability, exerting a pernicious influence over her that the young Victoria absolutely despised.

Paul Rhys Plays Sir John Conroy:

‘He was a self-made, ambitious man. To have got to that position of power in that time, coming from his background, was remarkable and speaks volumes for the intelligence of the man.

He was very loyal to the Duchess, who was constantly being marginalised, and he wanted her to have more power and title so he fought really hard for her. He was a fighter, a proper scrapper, and if it had been in a different direction it could have been for the greater good.’

ON 31 JULY 1832, on the eve of a three-month trip to Wales, Victoria excitedly contemplated the clean white pages of the brand new journal that her mother had given her. On the following day, she dutifully noted that ‘we had left K.P. At 6 minutes past 7’ and marked down the precise times and places where they had changed horses along the way: Barnet, St Alban’s, Dunstable, Stony Stratford. The road was dusty and it started to rain but she enjoyed every minute of this new adventure and the fact that the carriage went ‘at a tremendous rate’.

Throughout her journey Victoria painstakingly entered the details of their itinerary, the visits to Powis and Beaumaris Castles and the return home via Anglesey and the Midlands. Wolverhampton, she noted, was ‘a large and dirty town’, where she was nevertheless received ‘with great friendliness and pleasure’. A pause in heavy rain at Birmingham to change horses provided her with her first sight of the grim conditions in the manufacturing districts:

We just passed through a town where all coal mines are and you see the fire glimmer at a distance in the engines in many places. The men, women, children, country and houses are all black. But I can not by any description give an idea of its strange and extraordinary appearance. The country is very desolate everywhere; there are coals about, and the grass is quite blasted and black […] every where, smoking and burning coal heaps, intermingled with wretched huts and carts and little ragged children.

~ VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 2 AUGUST 1832

Soon, however, she was entranced by the more prepossessing splendours of the great country houses: Chatsworth – ‘It would take me days, were I to describe minutely the whole’ – Hardwick Hall, Shugborough Hall, Alton Towers and Wytham Abbey.

By 1835 the exhausting annual tours had taken a toll on Victoria, bringing her to the brink of physical collapse. Hours and hours of being jolted mercilessly along country lanes and potholed roads gave her headaches and backache. She suffered from travel sickness and in September, after another gruelling tour – of the Midlands, North Country and Norfolk – she became so run down that at Ramsgate she fell seriously ill with typhoid and took to her bed for five weeks. She was devotedly nursed back to health by Lehzen, who insisted on the seriousness of Victoria’s illness and that the doctors be called in.

Script quote:

Duchess of Kent:

When she was just a little girl she would show me her journal every night, so I would know everything she was thinking and feeling.

BY 1837 VICTORIA HAD matured considerably. For the last two years she had been engaged in a detailed correspondence with Uncle Leopold, in which she confidently discussed the intricacies of constitutional history, the workings of the British parliament, and world politics (not to mention enjoying a good gossip about all the family feuding and intrigue in the royal houses of Europe). Her letters to him demonstrate a precocious self-confidence and a lively interest in the workings of Parliament:

You may depend upon it that I shall profit by your excellent advice respecting Politics. Pray, dear Uncle, have you read Lord Palmerston’s speech concerning the Spanish affairs, which he delivered the night of the division on Sir Henry Hardinge’s motion? It is much admired. The Irish Tithes question came on last night in the House of Commons, and I am very anxious for the morning papers to see what has been done.

~ LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, 2 MAY 1837

On 24 May 1837 Victoria celebrated her eighteenth birthday and a public holiday was declared in Britain. King William sent her a splendid new grand piano as a birthday gift, Kensington Palace was decorated with bunting and the Princess awoke to a chorus of voices serenading her in the garden outside. She did not fail to note the significance of that day in her journal:

How old! And yet how far am I from being what I should be. I shall from this day take the firm resolution to study with renewed assiduity, to keep my attention always well fixed on whatever I am about, and to strive to become every day less trifling and more fit for what, if Heaven wills it, I’m some day to be.

~ VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 24 MAY 1837

The courtyard and the streets were crammed when we went to the Ball, and the anxiety of the people to see poor stupid me was very great, and I must say I am quite touched by it, and feel proud which I always have done of my country and of the English Nation.’

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 24 MAY 1837

26th May 1837

… The demonstrations of affection and kindness from all sides towards me on my birthday, were most gratifying. The parks and streets were crowded all day as though something very extraordinary had happened. Yesterday I received twenty-two Addresses from various places, all very pretty and loyal; one in particular was very well written which was presented by Mr Attwood from the Political Union at Birmingham.

LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, 26 MAY 1837

I trust to God that my life may be spared for nine months longer. I should then have the satisfaction of leaving the exercise of the Royal authority to the personal authority of that young lady (Victoria), heiress presumptive to the Crown, and not in the hands of a person now near me (the Duchess), who is surrounded by evil advisers and is herself incompetent to act with propriety in the situation in which she would be placed.

PUBLIC SPEECH BY KING WILLIAM AT STATE BANQUET, AUGUST 1836

17th June 1837

My Beloved Child,

… I shall today enter on the subject of what is to be done when the king ceases to live. The moment you get official communication of it, you will entrust Lord Melbourne with the office of retaining the present Administration as your ministers. You will do this in that honest and kind way which is quite your own, and say some kind things on the subject. The fact is that the present Ministers are those who will serve you personally with the greatest sincerity and, I trust, attachment. For them, as well as for the Liberals at large, you are the only Sovereign that offers them des chances d’existence et de duree. With the exception of the Duke of Sussez, there is no in the family that offers them anything like what they can reasonably hope from you, and your immediate successor, with the mustaches (The Duke of Cumberland), is enough to frighten them into the most violent attachment for you … The irksome position in which you have lived will have the merit to have given you the habit of discretion and prudence, as in your position you never can have too much of either …

LETTER FROM LEOPOLD TO VICTORIA, 17 JUNE 1837

THAT EVENING A SPECIAL ball was held for her at St James’s Palace, at which, for the first time, Victoria took precedence over her mother. King William had lived long enough to see Victoria reach her majority and, while Conroy and her mother’s hopes for a regency were not yet at an end, in Victoria’s eyes they most certainly were.

Events soon overshadowed those happy celebrations. By early June it was clear that the King was dying. Victoria wrote to Uncle Leopold:

The King’s state, I may fairly say, is hopeless; he may perhaps linger a few days, but he cannot recover ultimately. […] Poor old man! I feel sorry for him; he was always personally so kind to me, and I should be ungrateful and devoid of feeling if I did not remember this.

I look forward to the event which it seems is likely to occur soon, with calmness and quietness. I am not alarmed at it, and yet I do not suppose myself quite equal to all; I trust, however, that with good-will, honesty and courage I shall not, at all events, fail.

~ LETTER FROM VICTORIA TO LEOPOLD, 19 JUNE 1837

William IV died in the early hours of 20 June, bitter that his young heir had so determinedly been kept away from his court – ‘at which she ought always to have been present’ – by her mother, but relieved that he had protected the throne for Victoria from the ‘evil advisers’ who surrounded her. Victoria recalled that momentous day in her journal:

I was awoke at 6 o’clock by Mamma, who told me that the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here, and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sittingroom (only in my dressing-gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham (the Lord Chamberlain) then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning and consequently that I am Queen. Lord Conyngham knelt down and kissed my hand at the same time delivering to me the official announcement of the poor King’s demise.

~ VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 20 JUNE 1837

William IV: on his death Victoria became Queen.

Script quote:

Lehzen:

Drina, the messenger is here. With a black armband.

LATER THAT SAME DAY, Victoria met her Privy Council for the first time – alone. When her uncles came forward to pay homage, she managed ‘with admirable grace’ to prevent them from kneeling to her. In a quivering voice she acknowledged the challenge facing her:

This awful responsibility is imposed upon me so suddenly and at so early a period of my life, that I should feel myself utterly oppressed by the burden, were I not sustained by the hope, that Divine Providence, which has called me to this work, will give me strength for the performance of it, and that I shall find in the purity of my intentions and in my zeal for the public welfare that support & those resources that belong to a more mature age and to longer experience.

~ VICTORIA’S SPEECH TO THE PRIVY COUNCIL, 20 JUNE 1837

Britain seemed, overnight, transformed by the arrival on the throne of a young, untainted queen after a century of Hanoverian males. ‘Now everyone is run mad with loyalty to the young Queen,’ wrote Sallie Stevenson, wife of the American Ambassador. ‘She seems to have turned the heads of the young & old, & it is amazing to hear those grave & dignified ministers of state talking of her as a thing not only to be admired but to be adored.’

From his home in Saxe-Coburg, Victoria’s young cousin Albert sent his congratulations:

Now you are queen of the mightiest land in Europe; in your hand lies the happiness of millions. May Heaven assist you and strengthen you with its strength in that high but difficult task.

~ LETTER FROM ALBERT TO VICTORIA, 26 JUNE 1837

Script quote:

Victoria:

I intend to see all my ministers alone.

Conroy:

This is not a game. In future you must be accompanied by your mother or me.

Duchess:

Yes, Drina, you are just a little girl, you must have advisers

Victoria:

Oh, don’t worry, Mamma, I won’t be completely alone I have Dash.

I dressed dear little sweet Dash for the second time after dinner in a scarlet jacket and blue trousers.

VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 23 APRIL 1833

Feature:

DASH

VICTORIA’S SPANIEL

‘Little Dash is perfection’

– Victoria –

IN JANUARY 1833 SIR JOHN CONROY presented the Duchess of Kent with a little tricolour Cavalier King Charles Spaniel named Dash. Although the dog initially seemed very attached to her mother, Victoria quickly commandeered it. Within a month it was accepted that he was her dog, supplanting both the dolls and Lehzen as her dearest companion.

‘Dear little Dash is a most amusing, playful, attached and sweet little dog. He is so clever also,’ she wrote in her journal. She dressed him in a scarlet jacket and blue trousers and at Christmas that year gave him gingerbread and three rubber balls as presents. When she became Queen, Victoria worried about how Dash would settle in at Buckingham Palace but soon recorded in her journal that he ‘seemed quite happy in the garden’.

Once word got out that the Queen had a pet dog, many other dogs were offered as gifts. ‘You’ll be smothered with dogs,’ her favourite prime minister, Lord Melbourne, told her. And indeed Victoria was later to own a number of pet dogs: Waldman the dachshund, Islay the terrier, Sharp the collie, and there was, of course, Albert’s beloved greyhound Eos. But Dash was the Queen’s first and best-loved dog.

It was Albert who broke the news of his death to a heartbroken Victoria: ‘I was so fond of the poor little fellow, & he was so attached to me.’ She had him buried on the slopes of Windsor Castle near her summer house, and wrote a most touching epitaph:

Here lies Dash, the favourite spaniel of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, by whose command this memorial was erected. He died on the 20th December 1840 in his ninth year. His attachment was without selfishness, his playfulness without malice, his fidelity without deceit. Reader, if you would live beloved and die regretted, profit by the example of Dash.

VICTORIA’S FIRST ACT AS QUEEN was to give her assent to 40 new Bills. On a more personal level, that very first day, she had her bed removed from her mother’s room. She ordered the transfer of her household to Buckingham House – which she later renamed Palace, even though it was only half furnished and the carpets not down. Workmen were still busy day and night, and even the bronze entrance gates had not yet been fixed in position. She would miss Kensington Palace, writing:

Though I rejoice to go into B.P. for many reasons, it is not without feelings of regret that I shall bid adieu for ever (that is to say, for ever as a dwelling), to this my birth-place, where I have been born and bred, and to which I am really attached!

I have seen my dear sister married here, I have seen many of my dear relations here, I have had pleasant balls and delicious concerts here, my present rooms upstairs are really very pleasant, comfortable and pretty … I have gone through painful and disagreeable scenes here, ’tis true, but still I am fond of the poor old Palace.

~ VICTORIA’S JOURNAL, 13 JULY 1837

But for Victoria it was an important moment of transition. Propriety may have demanded that her mother stay with her until she married, but the needy, lonely Little Drina was no more. On 13 July 1837 the Queen left Kensington for what was referred to as ‘the New Palace at Pimlico’. She was Queen Victoria now, and in future the Duchess would not enter her rooms unless specifically invited.

Script quote:

Victoria:

But I don’t understand why this is called a House and not a Palace.

Melbourne:

You can call it whatever you want, Ma’am.