Читать книгу The Extraordinary Parents of St. Thérèse of Lisieux - Helene Mongin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Youth or the Desire for God

On July 13, 1858, Louis Martin married Zélie Guérin in the beautiful Notre-Dame d’Alençon Church. He was thirty-four and she was twenty-six. They had known each other for three months, but they didn’t doubt for a minute that this marriage was God’s will. This was not the vocation that these two fervent hearts had aspired to in their youth, however. The road that brought them to each other demonstrates how much “God writes straight with crooked lines.”

Louis was born on August 22, 1823, in Bordeaux. His father, Pierre-François Martin, was a captain in the French army who had participated in the Napoleonic wars and lived in various garrisons in Bordeaux, Avignon, and Strasbourg. In 1818, Pierre-François married Fanny Boureau, the daughter of one of his military friends, and supplied the dowry that she could not furnish. The offspring of this couple included Louis as well as four brothers and sisters (who all died young).

His parents’ faith was vibrant. One day when the soldiers asked Captain Martin why he stayed on his knees so long during Mass, he answered, “It is because I believe.” His relatives were equally taken by the manner in which he recited the Our Father. As for Fanny, she was a woman of prayer, as this extract from a letter sent to her son shows: “How often I think of you when my soul, lifted up to God, follows the impulse of my heart right to the foot of God’s throne! There I pray with all the fervor of my soul.”2 Louis was thus presented the Catholic faith from a very early age.

We know little about his early years. From garrison to garrison, those years were regulated by the military life that gave Louis his penchant for discipline and travel. In 1830 Captain Martin retired and went to live in his native region of Normandy in the city of Alençon. Louis didn’t attend secondary school but received enough education to demonstrate clear intelligence and discernment, especially in literature. He could have chosen a military career like his father; however, the French army had lost its luster since the end of the Napoleonic era. Louis had less of a penchant for adventure and more of an inclination toward interiority.

Discovering the delicate and detailed craft of watchmaking after visiting an uncle in that profession in Rennes, he fell in love with both watchmaking and Brittany. He lived there in 1842 and 1843, learning the basics of that craft while at the same time immersing himself in reading the great authors. He copied numerous texts in notebooks and from these we know that he particularly liked the Romantics, with a preference for François-René Châteaubriand, and he also appreciated the writings of Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, François Fénelon, and similar authors.

Louis’s literary tastes reveal an important character trait: he was sensitive to beauty whether in literature or in the landscapes of Brittany. Often, while walking in the countryside, he would stop to weep before the magnificent beauty of creation. Although romantic sensibility was common for this era, Louis’s sensibility was different insofar as he always discovered the Creator in whatever he was contemplating. Few things made him so happy as taking his pilgrim’s staff and walking around magnificent places while praying.

He did that for the first time in September 1843 when he crossed the Swiss Alps on foot and discovered the dream of his youth: the Grand Saint Bernard Monastery. The famous building is set at over 8,000 feet, and here the Canons of Saint Augustine divided their time between contemplation and mountain rescues. Prayer, beauty, heroism—this is what appealed to his young soul in love with the absolute.

For two years, Louis let the desire to enter this order mature in him while he continued his apprenticeship training in watchmaking in Strasbourg. They were good years. He made wonderful friends with whom he shared a joyful and prayerful youth. But he put an end to this period in 1845, wanting to return to the Grand Saint Bernard Monastery to answer what he felt was a call from the Lord. But then a disappointment occurred. The abbot, who was initially enthusiastic about this fervent and levelheaded young man, had reservations when he learned that Louis had not attended secondary school. To enter the monastery, young men needed to know Latin. He invited Louis to return after he went back to school and finished his studies. Louis returned to Alençon, and for more than a year he plunged into his books and took courses in Latin. An illness interrupted his efforts, however. Louis discerned a sign from Providence in that circumstance, and with a heavy heart he set aside his aspirations for monastic life.

He then decided to finish his training as a watchmaker in Paris. He was severely tested by Parisian life, experiencing numerous temptations: examples of dissolute life, an invitation to join a secret society, the influence of liberal Voltairean thinking, difficulty in keeping a prayer life in the hustle and bustle of the capital … According to his own testimony, it took a lot of courage for him to emerge victorious. From this time on, he relied not on his own strength but on God’s strength for his courage. The young Louis redoubled his prayer and entrusted himself to the Blessed Virgin in the sanctuary of the Basilica of Notre-Dame des Victoires, a church he always particularly liked.

Like gold tested in the crucible, Louis emerged purified from his time in the capital and relied on that experience for the rest of his life. He knew the temptations that life could bring and never stopped exposing them and encouraging his relatives not to fall into them.

Comforted by having a career well in hand, he returned to Alençon and set up a watchmaker’s shop on Rue du Pont-Neuf and later added a jewelry shop to it. Louis was twenty-seven years old, and the next eight years his life unfolded peacefully in prayer, work, reading, and recreation. Because of his cheerful, agreeable, and pensive character, he quickly made friends whom he regularly joined in the Vital Romet Club, a small group named after its founder (who was a great friend of Louis)—the members played billiards as well as studied their faith. He spent equally long hours at his favorite pastime, fishing.

In 1857 he bought a small property known as the Pavilion. It included an octagonal tower that he furnished simply, decorating its walls, as they do in monasteries, with pious sentences that revealed his spirituality: “God sees me”; “Eternity approaches and we do not consider it”; “Blessed are those who keep the commandments of the Lord.” He often went there to read and pray.3

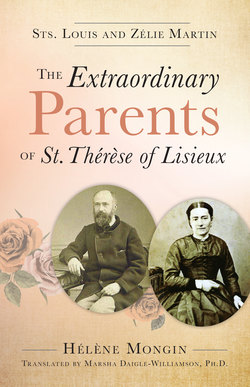

Father Stéphane-Joseph Piat gives us a wonderful description of Louis during this period: He was “tall in stature, with the bearing of an officer, a pleasing physiognomy, a high, wide forehead, fair complexion, a pleasant face framed by chestnut hair, and a soft, deep light in his hazel eyes. He looked like both a gentleman and a mystic and didn’t fail to make an impression.”4 Nor did he fail to attract the attention of the young girls in the city. But Louis categorically rejected any idea of marriage—he was still grieving over his unfulfilled desire for a monastic vocation. He even started studying Latin regularly again. More and more the life of this quiet young man of thirty-four approximated a quasi-monastic life in the world. But his mother was keeping her eye out. It was unthinkable for Fanny Martin to see her cherished son end up as a bachelor. She sought at all costs to see him married, and she ended up finding the rare pearl.

Marie-Azélie Guérin, called Zélie, was born on December 23, 1831, in Saint-Denis-sur-Sarthon in the Department of Orne. Similar to the Martin father, her father was a military man involved in the Napoleonic Wars who decided to retire in Alençon. His retirement pension was meager, so the family had to count every penny; Zélie never even had a doll. The family atmosphere didn’t seem to be the happiest. The father, Isidore Guérin, was a good but surly man, and his wife, Louise-Jeanne, was a woman with little affection who often merged faith and rigid moralism. Zélie would say of her childhood that it was as “sad as a shroud” and that because of her mother’s severity “my heart suffered a lot.”5

Zélie didn’t flourish any better on the physical level than she had on the emotional level. From the age of seven to twelve, she was continually ill and spent her adolescence tormented by migraine headaches. This did not, however, prevent her from receiving a good education with the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. Fortunately, she had a brother and a sister who played major roles in her life: Marie-Louise, called Élise, the older sister, her confidant and her support, who was as close to her as a twin; and Isidore, who was ten years younger and whom she loved as a mother would.

The Guérin family had also come from a strong Catholic tradition. They liked to tell the adventures of their great-uncle Guillaume who was a priest during the French Revolution. Sought out by the “Blues,”6 he went into hiding. One day, when he was bringing the Eucharist to a family, he was attacked by a band of rogues. He placed the Blessed Sacrament down on a pile of rocks, saying, “God, take care of yourself while I take care of these guys,” and threw his assailants into the nearby swamp. Another time he owed his life to the presence of mind of Zélie’s father who, when he was just a child, made believe he was playing on the chest in which his uncle was hiding from the soldiers. At the Guérin home, faith was rooted in their hearts even if it was tainted by the rigorous Jansenism that was rampant at that time.

Because of her sad childhood, Zélie could have been just an anxious, hypersensitive young woman full of scruples and lacking in self-confidence. She was actually all of those things, but from her youth she also demonstrated St. Paul’s axiom that “when I am weak, then I am strong” (2 Cor 12:10). Doubting her own capabilities, Zélie early on relied on God, knowing that his strength would never fail. Her relationship with him was so profound that before the age of twenty she believed she was called to religious life. As was the case for Louis, her choice of which convent to join revealed her generous personality: Zélie wanted to become part of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, apostolic sisters who combine a life of prayer and active service to the poor. But again, the Lord, who knows the hearts of his children so well, blocked her path. The superior clearly said that she didn’t believe Zélie had that vocation. For Zélie it was a hard blow, but she wasn’t one to wallow in her unhappiness. She decided to be trained in a profession.

During her years of study she had learned the basics of the noble craft of lace-making in Alençon. The Arachnean lace that Napoleon admired required intensive manual dexterity and delicacy. Zélie decided to pursue this profession and excelled at it. At first she worked in a factory in Alençon, but she attracted the persistent attentions of a member of the personnel so she decided to quit that job. On December 8, 1851, the feast of the Immaculate Conception, while she was working in her room, she heard an inner voice clearly say, “You are to make Alençon lace.” She immediately talked to her sister, Élise, who encouraged her and promised her support.

Both of them then launched an enterprise that was more than bold, as she admitted later: “How did we—without any monetary resources to speak of and without any understanding of business—end up doing well and finding establishments in Paris who would trust our work? Yet that is what happened in a very short time because we started working the very next day.”7 She wasn’t even twenty years old. Zélie established herself as a maker of Alençon-style lace and as the proprietor of that business.

Father Piat gives us another wonderful description, this time of Zélie:

Somewhat shorter than average, a very pretty and innocent face, brown hair in a simple style, a long well-shaped nose, dark eyes glowing with decision that occasionally had a shadow of melancholy, she was an attractive young woman. Everything about her was vivacious, refined, and amiable. With a lively and refined spirit, good common sense, great character, and above all an intrepid faith, this was an above-average woman who could draw people’s attention.8

As the years went by, divided between prayer and work, she bonded even more with her sister in the midst of the trials of starting up a business and the trial of an opposite vocation for Élise. Élise had been interested in cloistered life but had run into obstacle after obstacle because of health issues and attacks of scrupulosity. On April 7, 1858, she finally landed at the doorstep of the Visitation Monastery in Le Mans with the radical desire of becoming a saint. For Zélie the separation was heart-rending. At that time she could barely stand to be separated from her sister even for an afternoon. “What will you do when I am not here any more?” her sister had asked her.9 Zélie said she would leave too. And that is what she did three months after her sister entered the convent. She went in a new direction … to marry Louis.

Louis’s mother, Fanny Martin, was taking some lessons in lacemaking in Alençon and met Zélie, whom she immediately appreciated; with her solid maternal instinct, she saw in her an ideal daughter-in-law. She talked about her to Louis, doubtless presenting more arguments to him about her piety than her beauty. Louis’s resistance was overcome and he was open to meeting Zélie.

Zélie didn’t have an attentive mother to counsel her, but she had the Holy Spirit: Zélie crossed paths by chance with Louis for the first time on a bridge. Not only did his attractive appearance vividly impress her, but again an inner voice confirmed to her, “This is the one I have prepared for you.” Young people in the process of discernment could envy such clarity. But let’s not forget that Zélie, like Louis, had done all she could to find her vocation and had gone through deserts for it. She also had her heart open enough to hear the voice of the Holy Spirit in this way. The Spirit didn’t have to reveal the name of “the promised one” since Fanny Martin would take care of that a few days later.

The two young people met in April 1858 and quickly grew fond of each other, rapidly establishing a rapport. They got engaged, and with the consent of the priest who prepared them for marriage they decided to get married on July 13.

Nine children were born from this union. Louis and Zélie raised them while continuing in their watchmaking and lace-making professions. Five daughters were born who lived: Marie in 1860, Pauline in 1861, Léonie in 1863, Céline in 1869, and Thérèse in 1873. Four little “angels” left early for heaven: Hélène in 1870 (at the age of 5), Joseph in 1866, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph in 1867, and their first daughter named Thérèse, in 1870.

2 Father Stéphane-Joseph Piat, O.F.M., Histoire d’une famille [The Story of a Family] (1946; repr ed., Paris: Téqui, 1997), p. 13. Future references to this work will be indicated by HF and page number.

3 People can visit the Pavilion in Alençon, and no place reveals Louis’s soul better to a pilgrim than this place.

4 HF, p. 25.

5 Correspondence familiale (1863-1885) [Family Correspondence from 1863 to 1885] (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 2004), Letter 15. Future citations from this text will be listed as CF with the letter number.

6 The “Blues,” named for the color of their uniforms, were the troops supporting the new republic that fought against the peasants during the French Revolution.

7 HF, p. 29.

8 HF, p. 32.

9 CF 190.