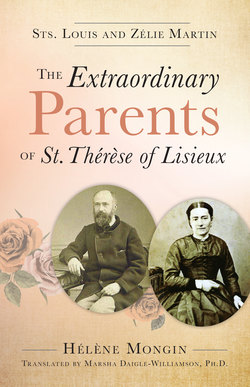

Читать книгу The Extraordinary Parents of St. Thérèse of Lisieux - Helene Mongin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

A Marriage of Love

What kind of couple were Louis and Zélie? Let’s look at their foundation in God as a couple on July 13, 1858.

They were married at the odd hour of midnight, a local tradition. Louis gave his wife a beautiful medallion representing Tobit and Sarah, the biblical couple. Tobit, during the night of his wedding, had prayed: “O Lord, I am not taking this sister of mine because of lust, but with sincerity. Grant that I may find mercy and may grow old together with her” (Tb 8:7).

Fifteen years later Zélie would tell her daughter Pauline the story of her first day of marriage, which wasn’t a typical first day for a young couple. After going to the convent to present her husband to her sister (now Sister Marie-Dosithée), she spent the day in tears. Seeing her sister as a nun awoke the suffering of their separation and stirred up her regret at the loss of a consecrated life, especially since she had just now committed to live “in the world” because of her marriage. But there is also a more delicate shock to recount: the prior evening, Louis had to explain to her “the things of life,” as they used to say for modesty’s sake—that is to say, the facts about sexuality, which Zélie had been perfectly ignorant of. It’s an ignorance we find astounding in our age, but it was quite common at that time.

One can easily imagine Zélie’s difficulty in absorbing these sudden revelations, a difficulty which could also explain her tears the following day. This is the point at which Louis—with an uncommon sensitivity—proposed that they live as brother and sister. The reasons for this proposition were not only the respect he had for his wife but also his aspiration to be a saint. He had studied the issue of virginity in marriage and his notebooks contain several texts on the validity of marriages that are not consummated, with Mary and Joseph being the perfect example. For these young people who had dreamed of consecrating themselves to God at a time when the perfection of virginity was highly praised by the Church, this seemed to be the solution: to marry, but to live in the marriage like religious.

We can smile at this plan today, but we need to understand the generosity and respect for the other that underlies it. Speaking in euphemistic words about this choice when she told Pauline about her first day of marriage, Zélie commented: “Your father understood me and comforted me the best he could since he had inclinations that were similar to mine. I believe our mutual affection was even more increased through this, and we were always united in our feelings.”10 Louis and Zélie had an experience of chastity similar to that of young people today who are chaste before marriage, and they testify by what followed to the solidity that such a choice produced in them as a couple. During this period, Zélie wrote to her sister how happy she was. They lived as brother and sister for ten months, meanwhile opening themselves up to life by taking in for a time a small boy that a recently widowed and overwhelmed father had entrusted to them. It was a time of maturation for them as a couple and of better understanding their vocation.

Little by little, Louis and Zélie discovered that their marriage—far from being a replacement by God for the failure of their plans to consecrate themselves—was their true calling, to be lived out fully. When their confessor invited them to set a time to end their abstinence, they were ready to accept it. The arrival of children confirmed them even more in their vocation: “When we had our children, our ideas changed a bit; we lived only for them; they were all our joy, and we never found our joy except in them. Nothing was too costly for us to do for them; the world was no longer a burden.”11 The one who would exclaim that she was “made to have children” maintained a great respect, as did her husband, for religious life but had no regrets. “Oh! I do not regret getting married,” she told her brother.12

God oriented their desire for holiness toward the state in life in which they would blossom the most: marriage, and in particular parenthood. Louis and Zélie recognized God’s call to have many children and—in their lovely phrase—“to raise them for heaven.”13 Contrary to their initial ideas, it was not in spite of marriage but in and through marriage that they were to become holy.

The couple they became was based on a solid friendship full of tenderness and cooperation that the years only served to deepen. After five years of marriage, Zélie wrote: “I am still very happy with him; he makes life very pleasant. My husband is a holy man, and I wish that all women could have such husbands.”14 Whenever Zélie talked to someone about her husband, she couldn’t help always adding the same adjective, “my good Louis.” It’s a small word, but it sheds a lot of light on their relationship. More than friendship, however, one can see the enormous place they had in each other’s hearts through the feeling of loss they experienced when they were occasionally separated. The letters they wrote to each other at those times demonstrated all the vibrancy of a love full of tenderness. Away on a trip with the children to visit her brother and his wife, Zélie wrote:

The children are delighted, and if the weather were good they would be at the height of happiness. But as for me, I find relaxation difficult! None of all that interests me! I am absolutely like a fish out of water that is not in its element and must perish! If my trip were to be prolonged, it would have that same effect for me. I’m uncomfortable and out of sorts, which affects my body and I’m almost sick because of it. Meanwhile, I try to reason with myself and rally from the sickness. I follow you in spirit all day long; I say to myself, “He is doing this or that right now.” I am longing to be near you, my dear Louis. I love you with all my heart, and my affection for you is increasing because I am deprived of your presence; it would be impossible for me to live apart from you…. I embrace you and I love you.”15

Does this sound like the excitement of a young married woman in love? Not in this case. This letter was written after fifteen years of marriage. Louis had become Zélie’s “element.” And when Louis in turn had to leave home for business, he wrote with his characteristic thoughtfulness:

My dear Friend, I cannot come back to Alençon until Monday. The time seems long to me, and I’m eager to be near you. I don’t need to tell you that your letter brought me great pleasure, except that I see you’re tiring yourself out too much. So I recommend calm and moderation, especially in your work. I have a few orders from the Lyons Company. Once again, don’t worry so much; we will end up, with God’s help, at having a nice little business. I was happy to receive communion at Notre-Dame des Victoires, which is like a little earthly paradise. I also lit a candle there for the whole family. I embrace you with all my heart while I await the joy of being reunited to you. I hope that Marie and Pauline are being very good! Your husband and true friend, who loves you for life.16

These rare letters reveal a cooperation that withstood the years and the minor difficulties that we can sometimes read between the lines. “When you receive this letter, I will be busy rearranging your work bench, so don’t get mad,” Zélie once wrote. “I will lose nothing, not an old square piece, not the end of a spring, nothing. And then it will be clean all over! You will not be able to say, ‘You only shifted the dust around’ because there will not be any…. I embrace you with all my heart; I am so happy today at the thought of seeing you again that I cannot work. Your wife, who loves you more than her own life.”17 The last words Zélie ever wrote to Louis were, “I am all yours.”18

Her letters and the testimony of her daughters let us see the kind of wife she was: joyful, lively, tender, open to everyone, confident of her husband, and full of humor, with a special gift for making fun of herself. The contrast is striking in terms of how she perceived herself as anguished, depressed, and far from holy. Anguish was present throughout her whole life, and she affirmed at times it was a veritable torment for her. When trials became too heavy, she let herself be overcome by what she called “dark thoughts,” but more and more her faith and the supportive presence of Louis helped her to overcome her suffering.

Zélie was a strong and holy woman not because she was without fears and weaknesses, but because despite them she gave of herself generously to others and to God, with a trust that was always wholehearted. Her great sensitivity gave her an exquisite discernment about others. Moreover, she was a woman of action. She worked for her family and in her business without letup and without taking time to coddle herself. Sensing within the need to give herself permanently, she responded with so much generosity that she died with her needle in her hand, so to speak, without ever having the least bit of rest.

Céline described her mother during the process of beatification of Thérèse as being gifted with a superior intelligence and extraordinary energy. Zélie described herself, without realizing it, when she wanted to instruct her brother on a choice for a good wife: “The main thing is to look for a good woman who is domestic, who is not afraid to get her hands dirty when she works, who does not spend time on her appearance except for what is necessary, and who knows how to raise children to work and to be holy.”19 Of course, all this advice lacks any romanticism. Louis and Zélie didn’t lack a romantic side, but at a time when marriages of love were the exception, Zélie’s advice demonstrates the common sense of a woman from Normandy. Zélie was a good wife for Louis, and he was very complimentary of her.

Calm and thoughtful, he assumed the responsibility for the family and supported his wife with great tenderness. People often said that he was a gentle man, at times implying that he was a bit soft, but he was far from being soft, and he was just as hardworking as his wife. His extreme gentleness at the end of his life—so striking to those around him—was acquired more by a faithful practice of charity than by any innate characteristic of his. Thérèse would say that, following the example of St. Francis de Sales, he had managed to master his natural vivacity to the point that he seemed to have the sweetest nature in the world.

Louis took concern for others no less than Zélie did. He was above all a man of great uprightness, tolerating neither injustice nor hypocrisy. His determined temperament was fully in play when it was a question of fighting for spiritual causes or against inequities. Despite not liking to write, he pestered officials with his letters to help a needy man be admitted into a home for the elderly. Zélie’s goodness softened his sharp angles, inspiring him by her example to have more mercy toward an undeserving worker or stopping him from getting too wrapped up in solitude. In addition to sharing the same native milieu, similar social ideas, generous hearts, and energy put to good use, Louis and Zélie had in common a preference for work that required finesse and patience, and, above all, they both had a thirst for God.

According to the unanimous testimony of their daughters and their family letters, the communication between the spouses was deep and real. They spoke frankly to each other and often knew what the other was thinking: “He didn’t need to say it; I knew very well what he thought.”20 Louis didn’t hesitate to tell his wife about his past temptations in Paris so that his story could be of help to her brother, Isidore, when he went to Paris to study. They likewise spoke about a thousand and one things concerning daily life and their children’s adventures. Their favorite topic of conversation was faith, and they liked to read the lives of the saints together and discuss them, sharing their impressions and edifying each other.

They also knew how to respect quiet times and give each other space to accommodate their differences: Louis would regularly go to the Pavilion property or leave on pilgrimage. Zélie in turn would take time to write letters to her brother and sister or to attend devotional meetings.

In terms of daily worries, large or small, they handled them together. Louis often reassured Zélie, who ever since her childhood had a propensity to worry. “Once again, do not torment yourself so much,” he would say. At the end of her life she wrote about her husband, “He was always my consoler and my support.”21 Zélie herself was also a support for him—for example, when Louis was concerned about her health: “I have seen my husband often torment himself on this issue for my sake, while I stayed very calm. I would say to him, ‘Don’t be afraid, God is with us.’”22 When worries entered the household, it was she, as the heart of that home, who cheered everybody up. Louis and Zélie were pillars for each other in a wonderfully harmonious way.

Of course, the couple had frictions that created small, unforeseen annoyances. Louis, for example, despite being a seasoned traveler, forgot one day to get off the train with his daughters when they were coming back to Alençon from Lisieux, which left his wife waiting eagerly at home with the uneaten meal that she had spent the morning preparing. Once the initial annoyance was over, she quickly laughed about it when she wrote about the incident to Isidore. Although they sometimes argued, it didn’t poison their relationship, as seen in the following anecdote. Pauline, who was seven years old at the time, approached her mother after hearing voices raised and asked if that was what people meant by “getting along poorly together.” Zélie burst out laughing and quickly told her husband who also laughed. From that time on Pauline’s inquiry became a family joke.

As with many couples, the major topic of disagreement concerned the children. Although Louis and Zélie were perfectly in accord on the general topic of education for their children, their opinions could diverge when it came to minor decisions. When Zélie took Céline to Lisieux with her when she was a baby, Louis thought it was madness. He himself sent Marie off to boarding school when she was sick, against Zélie’s advice (which caused an outbreak of measles throughout the whole school). Zélie’s accounts carry no resentment about all that and, on the contrary, show a healthy balance.

Louis made most of the decisions, as a man of his time and as a biblical man, so to speak: “Wives, be subject to your husbands, as to the Lord. For the husband is head of the wife as Christ is head of the church…. As the Church is subject to Christ, so let wives also be subject in everything to their husbands. Let each one of you love his wife as himself, and let the wife see that she respects her husband” (Eph 5:22-24, 33). The Martins perfectly embodied this model of a Gospel couple, giving it a human face.

Louis didn’t exercise his authority in a unilateral manner. He was open to discussion, and even when he didn’t adopt his wife’s views, he let her do things her own way. As the old saying goes, “What the woman wants is what God wants.” That was true in the Martin family as seen in this delightful story that Zélie related to Pauline:

As for Marie’s retreat at the Visitation Monastery, you know how he doesn’t like to be separated from any of you, and he had first expressly said that she could not go. I saw that he was adamant about this, so I didn’t try to plead her case. I just determined very resolutely to come back to the subject. Last night, Marie was complaining about this issue. I told her, “Let me take care of it; I always get what I want without having to fight. There is still a month to go and that is enough time to persuade your father ten times over.”

I wasn’t wrong because hardly an hour afterward when he came home, he started talking to your sister in a friendly way as she was energetically working. I said to myself, “Good, this is the right time.”… So I brought up the issue. Your father asked Marie, “Do you really want to go on this retreat?” When she said yes, he said, “Ok, then, you can go.” And you know he is someone who doesn’t like our absences and unplanned expenses, so he was telling me just yesterday, “If I don’t want her to go there, she will of course not go. There seems to be no end to all these trips to Le Mans and Lisieux.” I agreed with him then, but I had an ulterior motive because for a long time I’ve known how these things work. When I tell someone, “My husband does not want it,” it is because I don’t want the thing any more than he does. But when I have a good reason on my side, I know how to help him decide, and I found I had a good reason for wanting Marie to go on the retreat.

It’s true that it’s an expense, but money is nothing when it comes to the sanctification and perfection of one’s soul. Last year, Marie came back to me all transformed with fruit that lasted, but she needs to renew her supply now. Besides, that is also what your father essentially believes and why he yielded so nicely.23

Notice that if Zélie can so sweetly “manipulate” her husband it’s because they are essentially in agreement deep down. Besides, “manipulate” is the wrong word for a woman who, a few days later in writing to her daughter, picked up right where she had left off in her letter: “My dear Pauline, I stopped at that last sentence. Sunday night at 7:00 your father asked me to go out with him, and since I am very obedient, I didn’t finish the sentence!”24 These incidents emphasize Zélie’s feminine character, Louis’s flexibility, and above all their good mutual understanding.

To understand the life of the Martin couple we need to know about their relatives and their surroundings. Zélie’s closest relatives were her brother and sister. Although Louis rarely visited Sister Marie-Dosithée because she lived too far away, he was aware of her influence on his wife. Linked by blood and a deep friendship, the two women were also linked by a genuine spiritual sisterhood: “If you saw the letter I wrote to my sister in Le Mans, you would be jealous because it is five pages long,” she wrote teasingly to Isidore. “But I tell her things I do not tell you. She and I share together about the mysterious, angelic world, but I have to talk to you about earthly things.”25

What a shame that those letters weren’t preserved. They’ve disappeared, along with the letters to her daughters to prepare them for their first Communion that were so admired by the Visitation sisters. The letters that we have from Zélie only show her with a needle and a baby in each arm. But even this depiction reveals her deep interior life, and the major role her sister had on her path. As a confidant to her sorrows as well as joys, Sister Marie-Dosithée knew how to help Zélie discover God’s hand, as we shall see. Zélie never undertook any step in her affairs without entrusting it to the prayer of “the saint of Le Mans,”26 as she called her. This was especially true for family affairs.

As for Isidore, he was always the little brother they coddled. Zélie, together with Sister Marie-Dosithée, played a somewhat maternal role in his life. From Le Mans to Alençon, pious advice rained down on Isidore’s head. He pretended to mock it, but he appreciated it and ended up following it. In 1866, Isidore married Céline Fournet, a spouse completely along the lines prescribed by his sisters—good, pious, simple, and hardworking. The people in Thérèse’s circle said little about this quiet woman, but she was well loved by all the Martins. In 1875, Zélie wrote: “I have a sister-in-law who is incomparably good and sweet. Marie says she can find no faults in her, and I cannot either…. I assure you I love her like a sister, and she seems to feel the same way about me. She demonstrates an almost maternal attitude to my children and has given them as much attention as possible.”27 Isidore bought his father-in-law’s pharmacy in Lisieux and committed himself more and more to the life of the local church and also supported the Catholic newspaper in Lisieux.

Once Isidore was established in Lisieux, his relationship with Zélie was on a more equal footing. “I have known you for a long time,” she wrote to him, “and I know you love me and have a good heart. If I needed you, I am sure you would not let me down. Our friendship is sincere; it does not consist in pretty words, that is true, but it is no less solid and is built on stone. Neither time, nor any person, nor even death will ever destroy it.”28 All the letters she sent him showed this same affection.

Zélie shared in all her brother’s sentiments: When he lost a child she cried as though she had lost one of her own. She often wanted to spend a few days at her brother’s home in Lisieux—for her, and then for her children, going there was always a holiday. Isidore was also the medical adviser for the family, although he wasn’t always happy about that. The family submitted all minor health problems to him for his judgment, and then heeded it in a trusting manner.

The Martins, for their part, gave whatever help they could to the Guérin family: advice, monetary loans, and clients sent his way. The distance between the families was difficult to overcome, especially because each family was working and had babies, but the bond between them was nourished by frequent mail and always remained strong. The letters from Lisieux were read, reread, and passed around the family. And Zélie at times didn’t hesitate to get up at 4:30 a.m. to answer them. This bond was so strong for Zélie that in 1875 she wrote about Isidore and his family: “If I did not have a home and children here, I would live only for them, and I would give them all the money I earned. But since I cannot do that, God will provide.”29

Louis and Zélie’s life together evolved in the heart of the parish and the different Catholic circles where they visited with their few but close friends. The Romet, Maudelonde, Boul, and Leriche families and Mrs. Leconte regularly visited them on Rue du Pont-Neuf and, after 1871, at 34 Rue Saint-Blaise. Their second home—a small, charming, middle-class house facing the prefecture that can still be visited today—would be Thérèse’s first home and Zélie’s last. Zélie commented: “We are wonderfully settled in here. My husband has set up everything in a way that would please me.”30

As for worldly outings, they had few. Soon after their marriage, the young couple preferred intimate meetings instead of shallow balls at big parties. Zélie depicted the ridiculousness of high society when writing about an upcoming ball: “I know many young women who have their heads on backwards. There are some—can you believe it!—who make seamstresses come from Le Mans to sew their dresses for fear that the dressmakers in Alençon would reveal what their dresses look like before the celebration takes place. Isn’t that ludicrous?”31

Her letters are sometimes in the style of Madame de Sévigné32: she enjoyed relating pithy anecdotes to amuse the family in Lisieux about all the scenes in Alençon that struck her. But she was always able to recognize her own faults: “I had the cowardice to mock Mrs. Y. I have infinite regret about that. I don’t know why I have no sympathy for her since she’s been nothing but good and helpful to me. I, who detest ingrates, can only detest myself now since I am nothing but a real ingrate myself. I want to convert in earnest and I’ve begun to do that, since for some time now I take every opportunity to say nice things about this lady. That’s much more easily done since she is an excellent person who is worth more than all those who mock her, starting with me!”33

Louis and Zélie weren’t turned in on themselves but instead were attentive to what was happening around them. They read La Croix34 regularly, staying informed about local and national political developments because the anticlericalism of the time placed Catholics in jeopardy. Zélie was shocked to learn about the assassination of the archbishop of Paris and sixty-four priests during the time of the Commune. Listening to the prognosticators of ill omen, she feared for several months there would be a revolution. But her good sense won out: “The troubles have not come as predicted. I do not expect any will come for this year, and I have firmly decided not to listen to any prophet or prediction. I’m starting to become a very skeptical person.”35 After this experience, like other women in her time, she left politics to her husband. “I pay no more attention to external events than my little Thérèse does,”36 she wrote in 1874 when Thérèse was one year old.

Louis discussed politics with his friends and his brother-in-law and later even tried to introduce his views on the subject to Thérèse. Thérèse concluded, although we can doubt her objectivity, that if her father had been the king of France, things would have gone the best way possible in the best of all worlds. Meanwhile, Louis didn’t get involved in politics. His fight was on another level. He preferred concrete assistance to the poor around him rather than the grand declarations of leaders, and he preferred prayer rather than demonstrations. This is one reason that after the war in 1870 he joined 20,000 participants in an enormous pilgrimage to Chartres to pray for the nation. He had to sleep in an underground chapel where Masses were being said all night. He went back there again in 1873 and wrote to Pauline, “Pray hard, little one, for the success of the pilgrimage to Chartres that I want to be part of; it will bring numerous pilgrims in our beautiful France to the feet of the Blessed Virgin so that we may obtain the graces that our country needs so much in order to be worthy of its past.”37 There is no doubt that he would have resonated with St. John Paul II’s famous question, “France, eldest daughter of the Church, what have you done with your baptism?”38

Louis and Zélie were Catholics of their time for whom faith and patriotism were intertwined, living in fear of the anticlerical left and at the same time holding a firm conviction that the Lord was sustaining their country. The anticlericalism was a reality, though we have only a dim idea of it today. Louis, when he returned from a pilgrimage to Lourdes in 1873, was mocked in the train station in Lisieux because he was wearing a little red cross, and he was almost taken to the police station under the pretext that the mayor had forbidden pilgrims from coming back in procession. The disputes between Catholics and anticlerical groups increased during their lives, but in dealing with them the Martins always affirmed their faith in a nonviolent way.

10 CF 192.

11 Ibid.

12 CF 13.

13 CF 192.

14 CF 1.

15 CF 108.

16 CF 2.

17 CF 46.

18 CF 208.

19 CF 10.

20 CF 19.

21 CF 192.

22 CF 65.

23 CF 201.

24 CF 202.

25 CF 12.

26 CF 17.

27 CF 138.

28 CF 19.

29 CF 138.

30 CF 68.

31 CF 54.

32 A seventeenth-century French writer famous for her witty letters to her daughter.

33 CF 75.

34 A general-interest Catholic newspaper in France whose name means “The Cross.”

35 CF 80.

36 CF 120.

37 CF 102-a.

38 Pope John Paul II, on his first pastoral visit to France as pope in 1980.