Читать книгу Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche - Henri Lefebvre - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree Stars, One Constellation: Introduction to Hegel, Marx, NietzscheStuart Elden

__________________

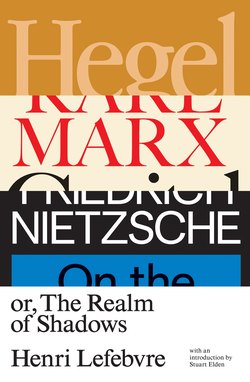

Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, or, The Realm of Shadows was first published in 1975, between The Production of Space (1974) and Lefebvre’s four-volume study De l’État (1976–8).1 The same year saw him publish a new autobiography, a re-edition of some of his essays on structuralism, and an edited collection on Fourier.2 Lefebvre was in his seventies at the time, and showed no signs of slowing down – several other significant studies followed, including the third volume of his Critique of Everyday Life, the posthumous Elements of Rhythmanalysis and the untranslated Une pensée devenue monde: Faut-il abandonner Marx?, La Présence et L’absence and Qu’est-ce que penser?3

Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche is a summation of Lefebvre’s considerable debt to these three thinkers, and its organization is clear. It is structured as three main chapters, ‘files’ or ‘dossiers’ on each thinker, framed by a long introductory chapter on ‘triads’ and a conclusion. Lefebvre suggests that the modern world is Hegelian, Marxist and Nietzschean, and while each of those claims separately is not paradoxical, put together they suggest an irreconcilable tension. How these aspects might be understood, and their relations teased out, is the focus of the study. Each thinker grasped something of the modern world, and shaped Lefebvre’s own reflections accordingly.

Lefebvre makes the claim that Hegelian thought can be summarized by the word and concept of the state, Marxism through the social and society, and Nietzsche through civilisation and its values. The state and its relation to civil society is of course the focus of Hegel’s Elements of the Philosophy of Right, and there is much else in his work, but Lefebvre stresses the political here. To take the state as the focus would be a Hegelian view of the world, but there is also a Marxist view, where the state’s relations to civil society, classes and industrial change are paramount. Yet this too neglects things that Lefebvre thinks are important, and he finds these in Nietzsche. This would include the assertion of life against impersonal political and economic processes, a stress on the importance of the arts of poetry, music and theatre, coupled with the hope of the extraordinary, the surreal and the supernatural.

The term royaume des ombres, the ‘realm’ or ‘kingdom of shadows’, or the underworld, is from Hegel’s Greater Logic, although it is also used in Marx, and in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche declares that the overman appears like a shadow. These three passages form the epigraphs to the present work.4 This poetic aspect is found throughout this book, Lefebvre likening the three thinkers to three stars in the sky – three stars in a single constellation:

Three stars gravitate, eliminating lesser or invisible planets, above this world in which shadows dance: ourselves. Stars in a sky in which the sun of intelligibility is no more than a symbol and no longer offers anything in the way of a firmament. Perhaps these stars vanish behind clouds hardly less obscure than the night …

In myth, from the poetry of Homer to the Divine Comedy, the realm of shadows possessed an entrance and exit, a guided trajectory and mediating powers. It had gates, those of an underground city, overshadowed by the earthly city and the city of God. Today, where are the gates of the realm of shadows? Where is the way out? (p. 49)

The links and tensions between Hegel and Marx are well known, and Lefebvre explores some of them here. Lefebvre argues that there is also much common ground between Marx and Nietzsche – their atheism and materialism; their critique of Hegel’s political theology, and of language, logos and the Judeo-Christian tradition; the stress on production and creation, and the body – though there is equally obviously much to contrast. Lefebvre suggests that Nietzsche’s proclamation that ‘God is dead’ has tragic repercussions more than simple atheism and naturalism; that for Nietzsche rationality is not just limited but also illusory; and that production and society are the focus for Marx, creation and civilisation for Nietzsche (pp. 192–93). Equally, while Marx renders Hegel’s dialectic materialist, Nietzsche makes it tragic. Civilisation, while it is discussed here and there in Marx, is distinct from the mode of production, and is most developed in Nietzsche. In Nietzsche, poetry and art take the place of knowledge, and the oeuvre is more important than the product. Nietzsche is obviously more interested in the individual, Marx the collective. While for Hegel and Marx it is the notion of Aufhebung – lift up, abolish or supersede – which characterizes the transitions of history, for Nietzsche it is the notion of Überwindung – overcoming (pp. 26, 31).5 In this and other later works Lefebvre tends to use the French term dépassement to grasp both processes together, though earlier in his career he had complained that the word was ‘contaminated by mysticism and the irrational’ because it also translates the Nietzschean term.6

We might further explore or challenge aspects of each of those readings, but Lefebvre works through each thinker in detail in turn in this study, and the strengths or limits of his readings can now be evaluated by his Anglophone readers. Instead, in this Introduction, I want to step back and discuss how Lefebvre reached the point where he could make these claims.

Marx

Lefebvre is best known as a Marxist, and one of his continual claims was that Marxism provides the essential framework to his ideas. He was a member of the French Communist Party between 1928 and 1958, but while he distanced himself from its organizational forms, he never moved away from this framework of thought. Lefebvre would often claim that he was interested in showing how Marxist ideas could be brought to bear on problems or issues that Marx himself had only treated in minor ways, if at all.

His lifelong project on the notion of everyday life, for example, draws on ideas of alienation, and explores how this can be found in many more aspects of the human condition. In the three volumes of the Critique of Everyday Life he published in 1947, 1961 and 1981, Lefebvre explored many dimensions, relentlessly examining new aspects and developing his theorization.7 To these three key moments we should add 1958, in which he re-edited the first volume with a long new preface; 1968, when he published Everyday Life in the Modern World; and 1992, when the book he was working on at his death, Elements of Rhythmanalysis, appeared.8

Equally, in The Sociology of Marx he suggested that while Marx was not a sociologist there is a sociology in Marx, and he explored how this might be the case.9 His work on rural and urban sociology draws on some of the claims made by Marx and Engels in The German Ideology and Engels’s work on the working class in England, but goes far beyond these works.10 This is both through detailed empirical work and through making substantial theoretical pronouncements. His doctoral thesis, for example, was a study of peasant communities in the Pyrenees, and he spent several years at Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique as a rural researcher.11 Seeing the transitions in and around his home town led him to his work on the urban condition. The now well-known works on the right to the city and the urban revolution developed from this.12 The Production of Space is the theoretical culmination of his studies of both rural and urban politics, as well as his detailed grounding in the philosophical tradition. Politically, Lefebvre would also make many important contributions, particularly evident in 1973’s The Survival of Capitalism and his books on the state.13

As well as these Marxist contributions, Lefebvre made several significant contributions to scholarship on Marx and Marxism. Right at the start of his career Lefebvre had worked with Norbert Guterman on Marx. Together, in 1928, they were two of the founders of the journal La revue marxiste, one of the first Marxist journals in France. Guterman was a Jewish émigré from Eastern Europe, and a multi-linguist. He and Lefebvre collaborated on many projects – Guterman taking the lead on translations; Lefebvre on introductions – until Guterman had to leave Europe just before the war broke out. Guterman settled in New York where he worked as a translator, and forged links with many of the members of the Frankfurt School. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Lefebvre and Guterman published the first excerpts from Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts,14 and in 1934 produced the collection Morceaux choisis de Karl Marx.15 Later criticized by Louis Althusser for not respecting chronology and mixing up material from different periods, without historical information,16 this collection actually showed Lefebvre’s long-standing insistence that we should read Marx as a whole. Nonetheless, its short excerpts and thematic organization means that it provides only a sampling of the richness of Marx’s work. Lefebvre wrote several books on Marx over his career, including Marx 1818–1883, Pour connaître la pensée de Karl Marx, The Sociology of Marx and Marx.

Marxist Thought and the City is one of the most successful of his books on Marx, developing a systematic reading of this theme in both Marx and Engels.17 Lefebvre also wrote books on Marxism, including the bestseller Le marxisme, for the popular Que sais-je? series.18 His 1947 book Logique formelle, logique dialectique was the planned first volume of a sequence of eight on dialectical materialism written in direct opposition to the Stalinist position.19 The second volume, Méthodologie des sciences, was written and printed, but publication was blocked by French Communist Party censors. It was finally published eleven years after Lefebvre’s death.20 In English, the most substantial statement comes in his early book Dialectical Materialism, as well as The Sociology of Marx. Dialectical Materialism and Le marxisme are two important works in stressing the importance of the theory of alienation to Marx’s work, showing that this term is not just central to Marx’s early writings, but crucial in his later discussion of reification, fetishism and mystification. In 1963 and 1966, Lefebvre and Guterman again collaborated on a two-volume selection of Marx’s texts for Gallimard.21 Unlike Morceaux choisis, this presents material chronologically, showing the development of Marxist thought. Relatively little of his extensive work on Marx and Marxism is available in English, so the chapter on Marx in the present volume is a valuable contribution in its own right.

Hegel

Throughout his long career, Lefebvre saw Marx’s work as important, indeed essential, to an understanding of our times, but not something that could stand alone. In a 1971 discussion with Leszek Kołakowski he declared that, to understand the present moment, Marx was the ‘unavoidable, necessary, but insufficient starting point’, even if the work was to be an ‘analysis of the deception or of the errors or the illusions that originated with the thought of Marx’.22 In Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche he suggests that Marx’s thought today is not dissimilar to Newton’s work in the light of the modern theory of relativity – a stage to start from, true at a certain scale, a date, a moment (p. 10). As such, Lefebvre continually pushes Marxism beyond simply a reliance on the writings on Marx, Engels and Lenin, and brings other thinkers into the dialogue. Hegel and Nietzsche were the only two other thinkers that he held up as significant to the same degree.

Hegel was a crucial thinker for Lefebvre from his earliest writings, produced as part of the group around the Philosophies journal in the 1920s, along with Guterman, Georges Politzer, Georges Friedmann and Pierre Morhange. It was through this work that Lefebvre and his colleagues first discovered Marx, and not unsurprisingly, Lefebvre always insisted on the importance of Hegel to understanding Marx. This was a concern throughout his career, and it is with the benefit of hindsight that we can see this as a fundamental challenge to the Althusserian project.23 Lefebvre also worked explicitly on Hegel. He plays an important role in the early work La Conscience mystifiée, written with Guterman, as well as in his short study of Dialectical Materialism.24 La Conscience mystifiée is important in terms of an attempt to work out why large parts of the working classes came to embrace fascism in the early 1930s. Lefebvre and Guterman also produced a selected works of Hegel for Gallimard in 1938, and translated Lenin’s notebooks on Hegel’s dialectic.25

Other figures in the post-war French reception of Hegel were undoubtedly more important. Foremost here were Alexandre Kojève’s famous lectures on Hegel, attended by an extraordinary audience including Louis Althusser, Raymond Aron, Georges Bataille, Maurice Blanchot, André Breton, Alexandre Koyré, Jacques Lacan, Emmanuel Levinas, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre and many others.26 Jean Hyppolite did not attend, since he was developing his own reading of Hegel and was wary of being influenced. Hyppolite’s translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, and his detailed study Genesis and Structure of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, together with his readings of the work on the philosophy of history and the Logic, were enormously influential.27 Hyppolite supervised several student theses on Hegel, including the recently rediscovered one by Michel Foucault.28

The story of the French reception of Hegel is widely discussed, but Lefebvre has an important minor role in it.29 His reading was one that was largely independent of Kojève’s influence. In his reading of Hegel and Marx together, he is perhaps more significant in terms of debates about Marxism.30 The presentation of Hegel’s work in the Morceaux choisis comprises short, almost aphoristic selections, from a few pages to a few lines. Hegel looks, superficially at least, a lot like Nietzsche. The Introduction stresses the importance of Hegel to Marxism, and the way he might be read in the contemporary context of fascism – the Introduction was written in 1938. Lenin’s notebooks similarly stress the importance of Hegel to Marx. The chapter on Hegel here is a helpful indication of key aspects of his reading.

Nietzsche

Lefebvre was also a pioneer in the French reading of Nietzsche. Many of Nietzsche’s books had been translated into French in the first half of the twentieth century, though like the English translations from the same period they were not always reliable. In the first part of the century Nietzsche was influential in a range of fields, and politically was read by both left and right.31 Things changed with the Nazi use of his works, and in the Anglophone world the German émigré Walter Kaufmann did valuable work after the war in rehabilitating his reputation as a philosopher, though at the expense of making him largely apolitical.32 In Germany, the pre-war work of Karl Jaspers and Karl Löwith was important in this regard too.33

In France, Lefebvre led the way with his own anti-fascist study Nietzsche in 1939.34 It can be seen as the third part of an informal trilogy of works condemning the rise of nationalism and fascism in Europe, along with La Nationalisme contre les nations in 1937 and Hitler au pouvoir, les enseignements de cinq années de fascisme en Allemagne in 1938.35 All these books shared the fate of being condemned by the occupying German forces following the invasion.36 Lefebvre holds Nietzsche no more responsible for Nazism than Marx is for state socialism (p. 39). Georges Bataille’s own significant book On Nietzsche, originally published in 1945, makes some similar moves in defending Nietzsche from the fascist appropriation, and makes brief reference to Lefebvre’s book.37 What set Lefebvre’s 1939 book apart was that, as well as his discussion of Nietzsche, it included translations of key passages, probably prepared with the aid of Guterman.

Nietzsche’s ideas of moments, time and history, his understanding of life, and his reflections on poetry, music and theatre were crucial inspirations for Lefebvre. Later work on space would also owe something to his influence. The later French interest in Nietzsche is quite widely discussed in the literature, given his importance to Foucault, Derrida and Deleuze, among others, but Lefebvre tends to have only a minor role in these studies.38 The chapter on Nietzsche here, the longest part of the study, is a very good indication of the importance Lefebvre put on his work.

Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche

As well as the three discrete chapters on each thinker individually, in the long opening discussion of ‘Triads’ and the brief ‘Conclusion and Afterword’, Lefebvre explores the links between them in a more systematic way. Yet Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche is not the only work in which Lefebvre explores the relation between these three key thinkers and his own ideas. Many of his books could be discussed here, but foremost among them would be Metaphüosophy.39 It equally can be found in some of his substantive works on other themes, notably in The Production of Space, written around the same time as this study, and in La Fin de l’histoire from 1970, which shows that Lefebvre was a significant theorist of time and history as well as space.

For too long, Lefebvre has been seen in English-language debates simply as an innovative thinker in two registers – his cultural studies work on everyday life; and his urban and spatial writings.40 Both are important aspects, certainly, but only two facets of his writings. The translation of Metaphilosophy has, one hopes, helped to indicate the broader reach of his theoretical endeavour. His theoretically catholic approach is especially well exemplified in this book. It provides an excellent orientation to how Lefebvre read, appropriated and utilized Marx. It demonstrates the crucial importance of his reading of Hegel, who was central in understanding his relation to Marx, the state, logic and dialectics. And it sheds a great deal of light on his relation to Nietzsche. In this book, written almost half a lifetime after his first engagement with Hegel, Marx and Nietzsche in the 1930s, he returns to these three figures with the benefit of many years of thinking about them and using their ideas. It was to be one of his last major philosophical writings but, over forty years since its publication, its themes remain surprisingly relevant today, especially since Lefebvre’s abiding interest is in how these thinkers enable us to think the world.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to David Fernbach and Adam David Morton for comments on an earlier draft.