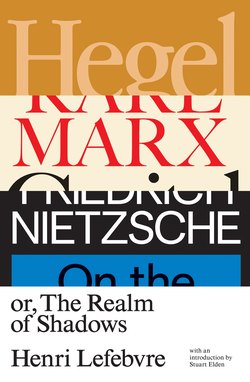

Читать книгу Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche - Henri Lefebvre - Страница 8

Оглавление1) Beginning without recourse to any cognitions1 other than elementary, any findings other than basic, we can put forward the following propositions:

a) The modern world is Hegelian. In fact, Hegel elaborated and drove to its ultimate conclusions the political theory of the nation-state. He asserted the supreme reality and value of the state. Hegelianism posits, in principle, the linkage of knowledge and power; it legitimizes it. Now, the number of nation-states has steadily risen (around one hundred and fifty today). They cover the surface of the globe. Even if it is true that nations and nation-states are no longer anything but façades and covers, hiding wider capitalist realities (world market, multinational corporations), these façades and covers are nonetheless a reality: not the most subtle, but effective instruments and frameworks. Whatever the ideology that inspires it, the state asserts itself everywhere, indissolubly using both knowledge and constraint, its reality and its value. The definite and definitive character of the state, conservative and even counter-revolutionary (whatever the official ideology, even ‘revolutionary’), is confirmed in the political consciousness it imposes. In this perspective, the state encompasses and subordinates to itself the reality that Hegel called ‘civil society’, that is, social relations. It claims to contain and define civilization.

b) The modern world is Marxist. For the last few decades, in fact, the fundamental concerns of so-called public authorities have been: economic growth, viewed as the basis of national existence and independence, and therefore industrialization, production, which leads to problems around the relation of the working class (productive workers) to the nation-state, as well as a new relationship between knowledge and production, hence between this knowledge and the powers that control production. It is neither obvious nor certain that knowledge should be subordinate to political power, or that the state has eternity on its side. Rational economic planning is on today’s agenda, achieved in different ways (direct or indirect, complete or partial). In the course of a century, industry and its consequences have changed the world, in other words, society, more (if not better) than ideas, political projects, dreams and utopias. As Marx had basically proclaimed and predicted.

c) The modern world is Nietzschean. If anyone wanted to ‘change life’, though these words are attributed to Rimbaud, it was certainly Nietzsche. If anyone wanted ‘everything right now’, it was him. Protests and challenges against the state of things are converging from all sides. Individual life and lived experience [le vécu] are reasserting themselves against political pressures, against productivism and economism. When it does not just oppose one policy to another, protest finds support in poetry, in music, in theatre, as well as in the expectation and hope for something extraordinary: the surreal, the supernatural, the superhuman. Civilization worries many people, more than the state or society. Despite the efforts of political forces to assert themselves above lived experience, to subordinate society to themselves and capture art, this contains the reserve of contestation, the resource of protest. Despite what is pushing it into decline. This corresponds to the raging wind of Nietzschean revolt: the stubborn defence of civilization against the pressures of society, state and morality.

2) None of the above propositions, taken separately in isolation, has the look of a paradox. It is possible to show that the modern world is Hegelian – or to refute it by classic procedures. If someone wants to prove it, they would have to reconstruct Hegel’s philosophico-political system as far as possible, on the basis of his texts. Then they would study the influence of this doctrine and its penetration by various paths into political life (the university, the interpretation of events, the blind activity of politicians, subsequently elucidated, etc.). The same holds for Marx – and for Nietzsche.

But, stated together, there is something intolerably paradoxical about them. How can this modern world be at the same time one thing and another? How can it pertain to doctrines that are diverse, opposed on more than one point, even incompatible?

Neither can it be a matter of influence, or simply reference. If the modern world ‘is’ at the same time this and that (Hegelian and Nietzschean …), it also cannot be a matter of ideologies that float above social and political practice like bright and dark patches, clouds and rays of light. An assertion of this kind forces us to grasp and define new relations between these theories (doctrines), as well as between the theories and practice. If this triplicity has a meaning, it is that each of them (Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche) grasped ‘something’ of the modern world, something in the process of happening. And that each doctrine, in so far as it achieved a coherence (Hegelianism, Marxism, Nietzscheanism), declared what it grasped, and by this declaration contributed to what was being formed in the late nineteenth century, to reach the twentieth century and across it, with the result that confrontation between these outstanding works involves a mediation, the modernity that they illuminate and that illuminates them. In an earlier book,2 these doctrines were confronted with historicism and historicity. Here, this critical analysis is expanded, while seeking to remain concrete.

If it is true that Hegelian thought is focused in one word and one concept, the state; that Marxist thought strongly emphasizes the social and society; and that Nietzsche meditated on civilization and values, then through the paradox we glimpse a meaning that remains to be discovered: a triple determination of the modern world, implying conflicts that are multiple and perhaps without end, within so-called human ‘reality’. This is a hypothesis whose scope permits us to say that it has a strategic import.

3) To study Hegel, Marx or Nietzsche in isolation, in the texts, would not take us very far; all textual connections have been explored, all deconstructions and reconstructions, without the authenticity of one or other interpretation prevailing. As for situating them in the history of philosophy, in general history or the history of ideas, the interest of such a contextual study seems as exhausted as does textual analysis.

What remains to be grasped, then, is their relationship with the modern world, taking this as the referent, as the central object of analysis, as the common measure (mediation) between the various doctrines and ideologies that insert themselves in it. The ‘contextual’ thus acquires an amplitude and scope, a richness of unknown and known, that is omitted when reduced to a certain particular or general history. In what way did Hegel, Marx and Nietzsche each respectively anticipate the tendencies of modernity in its nascent state? How did they grasp what was in the course of ‘taking’? How did they fix one aspect and define one moment among the contradictory aspects and moments?

Three stars, but one constellation. Sometimes the light from each is superimposed, sometimes one hides or eclipses the other. They interfere. The brightness of each either grows or pales. They rise or descend to the horizon, draw away from one another or converge. Sometimes one seems dominant, sometimes another.

The above statements have only a metaphorical significance and a symbolic value. They indicate the direction and the horizon. They declare (what remains to be shown) that the greatness of these works and these men is no longer like that of the classical philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, Descartes and Kant, who constructed a great architecture of concepts. This ‘greatness’ consists in a certain relationship to the ‘real’, to practice. So, it is not of a philological order, representable on the basis of language. New, metaphilosophical, it has to be defined on the basis of deciphering the enigma of modernity.

4) Let us look again at Hegelianism (nothing says that this will be the last look!). Enormous, pivotal, Hegel holds pride of place at the end of classical philosophy, on the verge of modernity. A solitary figure, yet he gathered together a historico-philosophical totality and subordinated it to the state. What makes for his ‘modernity’?

a) First of all, he gave systematic form to Western logos, whose genesis began with the Greeks, ancient philosophy and the ancient city. Like Aristotle, but after two thousand years, and taking into account what had been learned in the course of history, Hegel identified the terms (categories) of effective discourse and showed how they were connected in a coherent ensemble: a knowledge, source and meaning (finality) of all consciousness. Though impersonal, logos does not rest suspended in mid-air. Reason presupposes a ‘subject’ that is just a particular individual, an accidental person or consciousness. This rationality is embodied in the statesman, and realized in the state itself – with the result that the state is situated at the highest philosophical level, above the eminent determinations of knowledge and consciousness, concept and subject. It envelops these developmental conquests. It even encompasses logically, in a supreme cohesion, the results of struggles and wars, in other words, of historical (dialectical) contradictions. The state, as absolute philosophical ‘subject’ in which rationality is embodied, itself embodies the Idea, i.e. divinity. Hence those thundering declarations, which we shall have to return to, as it is impossible to let them settle into the false serenity and lying legitimacy of established philosophy, institutional and recognized as such. Since the state is ‘the actuality of the Idea’, objective spirit,3 the individual ‘has no objective, truth or ethical existence except as member of the state’. The state conceives itself through the thoughts of individuals who say ‘I’, and it realizes itself through individuals and groups who say ‘we’.4 The historical origin of the state (of each state) does not affect the idea of the state. Knowledge, will, freedom, subjectivity, are only ‘moments’ (elements, phases or stages) of the Idea as it is realized in the state, both in itself and for itself.5

Hegel thus legitimizes the fusion of knowledge and power in the state, the former subordinated to the latter. Organizational effectiveness and constraining violence, including war, link up and compete in the state, the former justifying the latter in a perfect reciprocity, and assembling in the political order things that seemed spontaneous (family, work and trades, etc.). The repressive capacity of the state is thus revealed to be basically rational, hence legitimate, which by the same token legitimizes and justifies both wars in particular and war in general. For Hegel as for Machiavelli, violence is a component of political life and the state. On top of which it has a content and a meaning; it opens the path of reason. Law (constraining) and right (normative) are necessary and sufficient for society and its complex mechanisms to function under the control of the state, and they denote the same political reality.

Thus the rationality inherent to all moments of history and to everyday practice is focused in the state. This legitimately and sovereignly totalizes morality and right (law), the social institutions and their particular functions (family, nations and corporations, cities and regions of the national territory), the system of needs and the division of labour (which corresponds precisely to needs). Just as consciousness has a triple origin (sensation, practical activity, abstraction), which raises it to the higher level of political consciousness, so the state has a triadic origin: productive work, history and its conflicts, and socio-political practice that brings it to perfection. These associated and interacting triplicities produce a living totality both organic and rational: the state. Viewed genetically, this is nothing other than reasoning humanity, obeying the call of the Idea, which produces itself in the course of history. In short, the state cements and crowns the social body, which without this would fragment into pieces, would atomize – if such a hypothesis makes any sense.

The Hegelian fetishism of the state may frighten the citizen or the reader of a philosophical work, and the summary that will be submitted (once more) to such a reader may perhaps appear monstrous, without any relationship to political reality. But this impression will fade as soon as the exposition goes into the detail of the Hegelian analysis and synthesis, which are striking and astonish by their character, both concrete and actual (modern).

b) According to Hegel, the rational, thus constitutional, state, has a social basis: the middle class. It is in this class that culture is located, which connects with the consciousness of the state. There is no modern state without a middle class, its foundation for both intelligence and legality.6 Neither the peasants nor the workers, the working and productive classes, can constitute pillars of the state. It is from this middle class that civil servants are recruited, either by co-optation or by competition.7 A competent bureaucracy, selected by tough examinations, is the true social basis and substance of the state.

For Hegel, there are thus social classes and even struggles (contradictions) between these classes: the natural class, the peasants, rooted in the soil; the active reflective class, artisans and workers, who produce the accumulation of wealth, these individuals being characterized by their (subjective) skill; and finally the thinking class, mediator between the two productive classes, and itself mediated by its knowledge, which maintains and manages the social whole within the context of the state. These three classes constitute civil society, with its intermediary (mediation) towards politics, in other words, the bureaucracy, emerging from the thinking class (middle: intermediary, mediating and mediated). Conflicts between these classes, the elements (moments) of civil society, press this outside and above itself, towards the establishment of a political class, directly (immediately, that is, without mediation) bound up with the state and thus constituting its apparatus. It is the upper fringe of the bureaucracy that constitutes (institutes in the constitution) the lower part of the personnel in power, around princes, monarchs and heads of state.

Thus, it is the contradictions (the internal dialectic) of civil society that engender the state and the political class. This latter, representing and effecting state action, can turn back on its own conditions; it has the capacity of recognizing (social) relations between the moments (elements, members, phases/stages) of civil society, of detecting their conflicts and resolving them, in such a way that the state is preserved as a coherent totality encompassing contradictory moments. With this aim, the ruling stratum (political class) is entitled to free itself from all other tasks and obligations, and consequently to receive prizes and rewards (honours, money) for exercising its responsibility. The result is that this fundamentally honest class, the summit of the pyramid, does not only represent the social substance: it is this substance, in other words ‘the life of the whole’, the constant production (reproduction) of society, state, constitution, the political act itself, which consists in governing.8

Philosophy, for its part, is the duplicate and shadow of the completed political system: the perfect philosophical system consecrates, legitimates, founds it. Philosophy as such is perfected in Hegelianism, which sums up and condenses its history; it finds full realization in the state to which the system brings theory. Philosophy accompanies the state as a public service. In the same way that the state rationally totalizes its historical, practical, social, cultural and other ‘moments’, so the philosophico-political system unites the rational and the real, the abstract and the concrete, the ideal and the actual, the possible and the accomplished. Knowledge (theoretical) and practice (socio-political) likewise coincide in administrative savoir faire.

The consequence, or rather the logical implication of this, is that history has reached an end. In terms of production, it has generated everything that it could generate. When? With the French Revolution and Napoleon.9 Why? Because the Revolution and Napoleon produced what supersedes and consecrates them: the nation-state. Marked by struggle and emergence – the figures of the individual and social consciousness, the phases of cognition – historicity re-produces its initial condition and its final content: the Idea. It contains three moments: productive work, self-generated conceptual knowledge and the creative struggle through which the higher moment is born from the lower, dominating this by subjecting (and thereby preserving) it. Origin (hidden) and end (manifest) of all things, of every act and every event, the Idea recognizes itself in the plenitude of the state. Accident and contingency are either non-existent, or no more than apparent. With the modern state time comes to an end, and the result of time is displayed (actualized in total presence) in space. This is the twilight of creation, the setting sun, the West! The trinity or speculative triad (work, action, thought) is completed in its triumph, and enters into its starry night. Into mortal wisdom.10

Who would not feel a frisson of terror at comparing the monstrous (monstrously rational) character of Hegel’s theory of the state with the concrete character of the detailed analyses that support and actualize this? The rise of the middle class above the working classes; the growing socio-economic importance of this middle class, combined with its illusory political importance; the subordination of this socio-economic ‘base’ to a bureaucracy; a technocracy; an upper class that emerges from the middle class; the formation of a political class – all these aspects of ‘modernity’ were grasped, foreseen, announced by Hegel at the start of the nineteenth century. Along with this was the revelation of another aspect that is overlooked, ignored or dissimulated in the modern world: the true portrait of the monster, seen from its cruelly thinking head to its active members – the superhuman and too human giant of the state.

We shall have to return to this paradox: Hegel’s tripod monster and his rational vision, the philosopher’s approval and the good conduct certificate given by philosophy, the juncture of knowledge and power, of Western logos and raison d’état, this intolerable ensemble of ‘truth’. Starting from this central conception: the Hegelian state produced its moments, its elements, its materials, in historical time. In the resulting space, it re-produces them in an immobile movement. Since ‘each member dissolves as soon as it sets itself apart’, the movement, the revolving sphere, the round, in a word, the system, are also ‘transparent and serene rest’, in the words of the Phenomenology of Spirit. Thus, the Hegelian state offers the model of a self-generated and self-maintained system that regulates itself, in other words, the perfect automatism.11 Architectonic colossus, necessary and sufficient, it is so. Es ist so. (These were supposedly the last words of the dying Hegel.)

5) Let us now reconsider what is currently known as ‘Marxism’. (Do I need to repeat that this is not the first time and will not be the last either?)

Preliminary remark: Hegelianism can be defined as a system. True, specialists in the history of philosophy are familiar with the difficulties arising from the diversity of Hegel’s texts and their dates. Agreement between Hegel’s phenomenology (description and linkage of figures and moments of consciousness, both for the individual and for humanity in its progress) and his logic (which includes the relation of formal logic, theory of coherence, with dialectic, theory of contradictions), as well as with history (sequence of struggles, violence, wars and revolutions), has nothing like Cartesian self-evidence. Yet we can be confident that Hegelian thought, in the course of the philosopher’s life, focused in a definable direction, that of the philosophical and political system.

What then of Marxism? This is only a word, a political label, a polemical amalgam. Only an outdated dogmatism still tries to find in Marx’s works a homogeneous body of doctrine: a system. Between the works of his youth, those of his maturity and those of his latter years, there is more than diversity, and anything but a quiet plant-like development. There are fissures, gaps, contradictions, incoherencies. Take dialectics, for example, which is first of all exalted and turned against Hegel like a weapon seized from the enemy, then denied and rejected, then taken up in a renewed form that Marx never clearly explained.

In so far as it is possible to draw a body of doctrine from a monumental work such as Capital, it refers to competitive capitalism, whose disappearance Marx foresaw and proclaimed. But why stubbornly stick to constructing an ensemble of this kind, given that the work was not completed? Why conceive it as a totality adequate to the mode of production that it analyses and explains, capitalism? It may well be that the final chapters, no less rich than the opening ones, contain discoveries that appear only by confronting them with what emerged from competitive capitalism in the twentieth century. Marx’s thought may today play a similar role as does Newton’s physics in relation to modern physics, the physics of relativity, nuclear energy, atoms and molecules: a staging post for going further, a truth at a certain level, a date – in a word, a moment – which prohibits, on the one hand, dogmatism, ‘Marxist’ rhetoric, and on the other, presumptuous discourse on the death of Marx and Marxism. Let us make this attitude clear right away; the reasons for it will appear later. It is not a question of reconsidering Marx’s thought, following the usual schema of ‘revisionism’, as a function of what has been new in the world over the last century. On the contrary: the correct and legitimate procedure consists in the determination of what is new in the world on the basis of Marx’s work. This is how changes in the productive forces, the relations of production, social structures and superstructures (ideological and institutional) manifest themselves.

Today there are multiple Marxisms, and it is a vain effort to try and reduce them to a single ‘model’. The thought of Marx and Engels was grafted on to concepts and values that were already widespread in the countries where it penetrated. Hence the birth of a Chinese Marxism and a Soviet (Russian) Marxism, of Marxist schools in Germany, Italy, France and the English-speaking countries. Hence the diversity and unevenness of theoretical development. The graft took either well or less well. In France, the Cartesian spirit, fundamentally anti-dialectical, offered neither a terrain nor a favourable ‘mentor’; the graft only bore fruit belatedly, which did not mean these were of poor quality.

What relationship did Marx’s thought have with that of Hegel? This question, which as everyone knows has led to a flood of ink being spilled, requires just one answer: Marx’s dialectical thought had a relationship with Hegel’s dialectical thought that was itself dialectical, which means unity and conflict. Marx took from Hegel the essentials of his ‘essentialist’ thought: the importance of work and production, the self-production of the human species (of ‘man’), the rationality immanent to practice, consciousness and knowledge, as also to political struggles, hence the meaning of history.

It is possible to find in Hegel (as also in Saint-Simon) almost everything that Marx said, including the role of work, production, classes, etc.,12 with the result that it is impossible to deny the continuity between the two thinkers. Yet the order and linkage, orientation and perspective, content and form, differ radically, so that the impression of a brusque discontinuity is no less striking than that of an uninterrupted continuity.

Throughout his life, Marx struggled against Hegel, to wrest from him his ill-gotten gains and transform these by appropriating them. What was Hegel for Marx? At the same time the father, possessor of the inheritance, and the boss and owner of the means of production, acquired knowledge.

In their struggle, there was a generational quarrel but also a class struggle. This combat went through phases with varying fortunes: highs and lows, victories and defeats, by one or other combatant. The stakes changed: either knowledge as totality or dialectic as method, or the theory of the state, etc. Contrary to Hegel, Marx used whatever he could lay hands on. He passed Hegelianism through the sieve of anthropology (Feuerbach), political economy (Smith, Ricardo), historiography (the historians of the French Restoration, especially Adolphe Thierry and the history of the Third Estate), philosophy (French materialism of the eighteenth century) and nascent sociology (Saint-Simon and Fourier). From this sieving and filtering, this critical negation, emerged a different thought and above all a different project, ‘Marxism’, built from the materials of a reprised and metamorphosed Hegelianism. This struggle ran from radical critique of Hegel’s theses on law and the state, on philosophy (the so-called Young Marx, 1842–5), to refutation of the Hegelian political strategy accepted by Ferdinand Lassalle (Critique of the Gotha Programme, 1875). No one today is unaware of how Marx understood and approved the Paris Commune, as destructive of the state. He opposed this revolutionary practice to the state socialism that was unfortunately coming to dominate the German workers’ movement, and would do so for a very long period, as it still persists today. In the course of this theoretical struggle, Marx never lost sight for a moment of the practical objective of the real stake, which is not the constitution of a system opposed to Hegelianism, but analysis of social practice and the modern world, in order to act and transform these on the basis of their immanent tendencies.

Continuity and discontinuity. There is therefore a ‘break [coupure]’, a point of rupture. Where should we situate this? Drawing on both texts and contexts, we can maintain that this break was neither philosophical (transition from idealism to materialism) nor epistemological (transition from ideology to science). These two aspects are encompassed in a more complex break, richer in both content and meaning: a political break. It was not true, for Marx, that philosophy (reason and truth, fullness and happiness as conceived by the philosophers) was realized in the state and ended in a constraining system. The working class would realize philosophy by a total revolution. But this was no longer classical philosophy (abstract, speculative, systematic); the realization of philosophy is accomplished in practice, in a way of living. By superseding traditional philosophy, by superseding itself, the proletariat opens up limitless possibilities. Time (so-called ‘historical’ time) continues. Hegelian superseding (Aufhebung)13 takes on a quite different meaning: the state itself has to be dispensed with through the ordeal of supersession. The revolution breaks it and leads to its withering away; it is absorbed or reabsorbed in society. Thus, the political break presupposes the philosophical break (rupture with classic philosophy) and the epistemological break (rupture with ideologies, those of the dominant class) as its moments. As for reason, it has no definitive form or formula. It develops through superseding: by resolving its own contradictions (between the rational and the irrational, the conceived and lived experience, theory and practice, etc.).

Thus, the state does not possess any higher rationality, still less a definitive one. Hegel takes it as the structure of society, while for Marx it is only a superstructure. It is constructed, or rather people – politicians, statesmen – construct it on a base, the social relations of production and ownership, the productive forces. The base then changes. So, the state has no other reality than that of a historical moment. It changes along with the base; it is modified, crumbles, is rebuilt differently, then perishes and disappears. As the productive forces advance from the use of natural riches to the technical mastery of nature (automatism), and from divided labour (alienated-alienating) to non-labour, the state cannot but be transformed. It has already changed profoundly from the feudal-military period to the monarchical period, and from this to the democratic period introduced by industrialization. Capitalism and the hegemony of the bourgeois class accommodate themselves to a democracy simultaneously liberal and authoritarian. This democracy and its state (parliamentary) are only for a time.

History, which according to Hegel had been completed, continues for Marx. Uncompleted time does not freeze (reify) in space, the space of commercial relations, industrial production or state domination. The production of things (products) encompasses the production of social relations; this double production, too, cannot be frozen (reified) into a simple re-production of the same things and the same relations. Thus, there is no re-production of the past or the present without the production of something new. This is the original form that the Hegelian dialectic acquires with Marx. The revolutionary creation of new relations cannot be avoided, even by the use of political instruments, constraint and persuasion (ideological). Rationality? This turns out to be inherent to social practice, and culminates, though without conclusion, in industrial practice. The everyday? Transformed along with social relations, it will bring happiness to men, Marxist optimism intrepidly maintains.

As for the state, a double movement runs through it. On the one hand, it manages the whole society in terms of the hegemony of the dominant and ruling class: in terms of its present interests and its strategic projects. It accordingly generates an educational system, practical knowledge [connaissance] and ideologies, social ‘services’ such as medicine and teaching, according to the interests of the hegemonic (dominant) class. At the same time, it raises itself above the whole of society, with the result that those individuals who possess the state (whether fraction of the hegemonic class or déclassés) may end up dominating and even exploiting for a time the economically dominant class, taking away its hegemony. This happens with Bonapartism, fascism, a state resulting from a military coup, etc. This contradiction internal to the state is added to the external contradictions that arise from its conflictual relations with its base, itself pervaded by contradictions. Hence the impossibility of a stabilization of the state. A provisional form of society, with its more or less integrated moments (moments, in other words, more or less dominated and appropriated: knowledge and logic, technology and strategy, law and moral ideology, etc.), the state does not rest on the middle class. Its base does not coincide with this class, but encompasses all social relations. Today, accordingly, it is the state of the bourgeoisie. It needs a bureaucracy, which effectively means a middle class, which tends to become parasitic as well as ‘competent’, by raising itself above the whole society along with the state (not without conflicts with the owners of the means of production, that is, with the other fractions of the ruling class).

Marx places at the centre of his analysis of the real, and likewise of his project, the social force able to overturn the state and the social relations on which it is based and which transform it, in other words, to destroy it first of all so as to bring it to an end. If the working class asserts itself by becoming a ‘collective subject’, then the state as ‘subject’ of history will die. If the state escapes this fate, if it does not collapse, if it does not fracture and wither away, this means that the working class has been unable to become an autonomous collective subject. By becoming autonomous, the working class replaces the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie with its own hegemony (its dictatorship). What prevents the self-determination and assertion of the proletariat as ‘subject’, as ability to manage the means of production and the whole society? Violence. Violence is inherent to the ‘subject’ when it breaks obstacles; this is its only meaning and scope. In the case of the working class, violence puts an end to the state, and to politicians raising themselves above the social. Proletarian (revolutionary) violence self-destructs instead of destroying the world. By itself it produces nothing, is in no way creative. We may say of violence that it is a permanent quality or ‘property’ of a self-asserting social being. According to Marx, this class cannot realize itself without superseding itself. By this act, it realizes philosophy by superseding it. For Marx, the social can and must reabsorb the two other levels of so-called ‘human’ reality, on the one hand politics and the state (which lose their dominant character and wither away), and on the other hand economics, the productive forces (which organize themselves within society, by a rational management according to the interests of the producers, the workers, themselves). The social, and consequently social needs, those of society as a whole, define the new society that is born from the old by revolution; socialism and communism are characterized on the one hand by the end of the state and its primacy, and on the other hand by the end of economics and its priority. In the ‘economic-social-political’ triad, it is the social and society that Marx emphasizes, and the concept of which he developed. Some would say that he banked on the social against the economic and the political, which had priority before the reversal of this world in which they had primacy. Others would say that Marx established a strategy on the basis of analysing tendencies in the real (the existing), with the social asserting itself as such.

Marxist thought is inspired by an immense optimism (an optimism that many people today label with a word that has lost its favourable connotations and is seen as denoting an uncertain naïvety: humanism). Happiness would arise from the conflictual play of forces, and especially from the conflict between nature (the spontaneous creation of wealth, reserves and resources) and anti-nature (work, technology, machines). The triad of nature, work and knowledge is the bearer of fortune.

A certain paradox continues to surprise, always new despite being very well known: the lasting influence of this optimism, despite its repeated setbacks. Marxism has failed, particularly and especially in the large number of countries that claim to adhere to it. In these so-called socialist countries, specifically social relations (association, cooperation, self-management [auto-gestion], etc.) are crushed between economics and politics, to the point of having no acknowledged existence; they are reduced, as in capitalist countries, to ‘private’ relations, personal communication in everyday discourse, the family, relations of formal socializing and business, at best to friendship or complicity. This crushing of the ‘social’ under the banner of socialism adds a further mystification to an already long list (rationalism against reason, nationalism against the nation,14 individualism against the individual, etc.). In this strange list, certain labels gradually fall into disuse (rationalism, for example, and its relationship with the irrational and the rational), but others take their place; ‘socialism against the social’ is a good replacement for any other opposition that is now obsolescent.

And yet, here or there, a ray of sunlight breaks through. It emerges from the economic against the political,15 which shows the complexity of the situation. Failures of Marxist thought? Yes. Death? No.

This situation is eminently paradoxical, and also one we shall have to return to.

6) We turn now to Nietzsche and Nietzschean thought (in as much as this is still a ‘thought’). This does not mean that the following reflections exhaust the situation of which this thought is part. We should not approach it without circumspection. ‘The Cartesian mind is seized by terror as soon as it enters the world of Nietzsche.’16

History? For Nietzsche as for Marx, contrary to Hegel, it continues – under a double form: on the one hand, absurd wars, endless violence, barbarities, genocides; and on the other, an immense, cumulative knowledge, ever more crushing, made up of scholarship, quotations, an amalgam of actions and representations, memories and techniques, speculations that are of little interest but supremely ‘interested’. What continues, therefore, is not history (historicity) as conceived by Hegel, a genesis of ever more complex realities, productive capacities that finally culminate in the edifice of the state. Nor is it history according to Marx, leading towards neither divinity nor the state, but towards ‘humanity’, the fullness of the human species, perfection of its essence, domination over matter and appropriation of nature. The Hegelian hypothesis (which Nietzsche was familiar with, and attacked violently in his Untimely Meditations),17 and the Marxist hypothesis (which Nietzsche rejected, via Hegel, without knowing it), were for him no more than theological. They presupposed that thought or practical action had a meaning, without demonstrating this. They postulated a direction: an immanent rationality, a divinity in humanity, or in the world. But God is dead! The atheism of Feuerbach, Stirner or Marx misunderstood the import of this assertion. Philosophers and their accomplices continued to reason – to philosophize – as if God were not dead. But along with God died history, man and humanity, reason and rationality, finality and meaning. Whether proclaimed by theologians as a higher entity, or secularized, placed in nature or in history, God was the support of philosophical architectures, systems, dogmas and doctrines.

What then is history? A chaos of chances, desires, determinisms. In this Nietzschean triad, taken over from the Greeks, chance holds the first place. The revelation and acceptance of chance, even the apologia for it, give a new dimension to freedom, declares Zarathustra, by breaking the slavery of finality. There is no event without a conjunction or conjuncture of forces initially external to one another, which meet up at a point in space and time where something happens in the wake of this encounter. Chance offers opportunities, favourable conjunctures (the kairos of the Greeks). ‘Chances end up being organized according to our most personal needs’, wrote Nietzsche. Why? Because what emerges in the face of analysis as well as in life is the will: not the pallid ‘faculty’ of classical psychology, the will of the subject who says ‘I want’, but the will to power [puissance], the active energy that seeks not a particular advantage from power [pouvoir], but power for itself: to dominate. As Hegel saw, following Heraclitus, there is struggle, combat, war; but for Nietzsche, the struggle of wills to power replaces Hegel’s rational historicity and dialectical overthrow (which Marx followed, modifying the Hegelian terms), an overthrow through which the slave conquers the conqueror (the master), so advancing in the direction of history. The third term of the triad: determinism, necessity. According to Nietzsche, there is not and cannot be a unique necessity, an exclusive determinism (physical, biological, historical, economic, political, etc.). There are multiple determinisms, which are born and die, grow and disappear after having undergone a certain path, played a certain role in nature or society. A role more often disastrous than beneficial …

So, history is not strictly speaking a chaos; it can be analysed and understood; but the understanding of history shows it to be irreducible to an immanent rationality, a progress determinable in advance. In any historical sequence, elements and symptoms of decadence can be discerned, even within something still strengthening. The shocks of violence shatter anything that seeks to establish itself in a fixed mould. Partial determinisms (biological, physical, social, intellectual) allow genealogies, such as that of a particular family, a discovery, an idea or a concept, far more than they do geneses, explanations by a producing activity.

Hegel, and Marx after him, refused to disconnect the rational from the real. They took the point of view of a logico-dialectical identity of the two terms (unity in contradiction and struggle, victory of a third term born from this struggle). According to Nietzsche, however, this is the root of a fundamental error. It rationally associates fact with value or meaning; but facts have no more meaning than a pebble on a mountain or an isolated noise. As for nature, it has no meaning, rather offering the possibility of countless meanings, in a mixture of cruelty and generosity, joy and suffering, pleasure and pain – a mixture with no name. ‘Man’, by a choice, confers a meaning on nature, on natural life, on the things of nature. ‘Man’ is not a ‘being’ that endlessly questions the world and himself, but a being that creates meanings and value – which he does as soon as he names things, evaluating them by speaking of them. Very likely, there are only facts and things for and by such evaluation. Does knowledge contribute a value, does it give meaning to objects and things? No, says Nietzsche against Hegel. In fact, as ‘pure’ and abstract knowledge, it strips the world of meaning. As for work, Nietzsche agrees with Marx that it has and gives meaning and value, but not the labour that manufactures products, only work that is creative. ‘Who evaluates? Who names? Who lives according to a value? Who chooses a value?’ This is how the question of the subject is posited, to which a response is necessary in order for the quest for a new meaning to retain a meaning – a question that it is hard to answer, since the answer presupposes a return to the original, by giving the ‘subject’ and its relationship with meaning a genesis. Hence Nietzsche’s uncertainties (significant in themselves). Sometimes he says that peoples invent meanings, create values. The philosopher and the poet keep aloof from the crowds, yet they emerge from the peoples, even and especially when opposed to their people.18 It is peoples that invent, and not states or nations or classes, which give no more meaning and value to anything than does knowledge or politics. This thesis posits in principle a complete relativism, a ‘perspectivism’ that is nonetheless convergent with Marxist positions, as it attributes to peoples, and consequently to the ‘masses’, the creative capacity of generating a perspective on the basis of an evaluation. Sometimes Nietzsche replies on the contrary that only the individual (of genius) has this capacity – an ‘elitist’ position: ‘We, who indissolubly perceive and think, we ceaselessly bring to birth that which is not yet’, he proudly declares in Die fröhliche Wissenschaft. Nietzsche’s thought, in other words, in as much as it is a thought, does not flinch from contradictions and incoherencies. But is it necessary to choose between these propositions? Are we faced with a system, a knowledge, or rather the transition from one knowledge to another, from sad science to Gay Science?

What then is this ‘gay science’, opposed both to the absolute science of Hegel and the critical science of Marx? Without awaiting a deeper reconsideration of this central point, it is useful to give right away here the genealogy of the fröhliche Wissenschaft. It has its origin in what is deepest in the West: a subterranean current combatted and buried by Judeo-Christian morality and Greco-Roman logos, against which Nietzsche waged a combat that was all the more terrible in that this was the matrix from which he himself emerged, which gives this struggle an exemplary and paradoxical character.

At the origin of Christian thought we have a work both illustrious and misunderstood, Augustinianism, relegated into the shadows by official doctrine. Augustine contemplated with all the resources of Greek, Platonic and Judeo-Alexandrian philosophy, in other words, with all the still-fresh memories of the Roman tradition, on the specific characteristic of Christianity, the doctrine of the fall, of sin and redemption. He interpreted the image of the mundus, of Greco-Italian origin, as a function of ordeal and purification by pain: the hole and the gap, the abyss deepening in the earthly depths, the shadowy corridor opening to the light by a path hard to find, the trajectory of souls who return to the maternal womb of the earth to be later reborn. The mundus: a ditch in which newborn infants were abandoned when their father refused to raise them, along with the condemned to death, refuse, corpses that were not returned to the celestial fire by burning them. Nothing was more sacred, that is, more accursed, more pure and more impure. The ‘world’: an ordeal in darkness to gain redemption, light. ‘Mundus est immundus’, Augustine proclaimed, at the dawn of the Christian world – the moment when the pagan world collapsed. He had found a motto for Christianity, its slogan.

Augustine, the first Westerner, did not posit in principle a ‘something’ pertaining to knowledge, whether an object (like the majority of the pre-Socratics: water, fire, atoms, etc.) or a subject (such as the noûs for Anaxagoras, or the active intelligence for Aristotle), or again an absolute knowledge (the Platonic Idea, forerunner of the Hegelian). For Augustine, being was defined (if we may put it this way) by will and desire, not by knowledge. Being (divine) is desire and infinite: desire not inherently finished, thus inexhaustible, and desire for the infinite, for another being equally infinite. This makes possible a presentment – like the sun through the clouds – of the mystery of the divine triad, the Trinity. Man in the image of God, the analogue of the divine, initially is infinite desire. The fall and sin broke this subjective infinity by separating it from its infinite ‘object’. If the ‘world’ is no more than a heap of filth, reason is revealed in the rupture and finitude of desire. Fallen into the dereliction of the finite, desire seizes on finite objects but encounters there only anxiety and frustration, in place of the infinite joy that it still and always senses. Rampant in the darkness of the mundus, this broken desire, divided from itself and yet reduced to pursuing only itself (in ‘self-love’), this infinite desire fallen into the finite is nothing other than libido, yet not unique but triple. According to the Augustinians there are three libidines, at the same time inseparable in fallen being and yet clearly distinct: libido sciendi (curiosity, knowledge and the need for knowledge, a need always disappointed and always reborn, attracted towards each thing instead of probing its own corruption and its own failure); libido sentiendi (the concupiscence of the flesh, the need for enjoyment, the endless and always disappointed pursuit of physical pleasure, a parody of infinite love), and finally libido dominandi (ambition, the need to command and dominate: the will to power). The triple libido of the Augustinians re-produces derisorily, in the dereliction of the finite, the divine triplicity of the Father (true power), the Son (the word, true knowledge and wisdom) and the Spirit (true love). Each libido is only the shadow of infinite desire, only desiring itself (self-love) through finite objects.

What relationship does this have to Nietzsche, other than purely abstract? In what way does Augustinianism (crushed by a theory of absolute knowledge, Thomism with its Aristotelian origin, which would pass through the sieve of Cartesian critique without suffering too great damage, and continue as an ingredient of Western logos) form part of the genealogy of Nietzschean thought? By way of seventeenth-century France. The underground current of Augustinianism inspired constant protest against the official theology of the Catholic Church; it also sustained protest against the establishment of the centralized state, the absolute royal power supported by raison d’état and knowledge: Jansenism against Louis XIV. Jansenism, however, was not confined to the thought of Cornelius Jansen, Saint-Cyran, Pascal and Port-Royal. It passed into literature: in Racine, and above all in La Rochefoucauld. Augustinian libido was referred to as ‘self-love’ in this author’s Maxims, which cruelly analyse all forms of self-love to denounce its detours and masks: ambition, the search for pleasure, curiosity.19 La Rochefoucauld, a sophisticated duke, was well acquainted with worldly society and knew what should be known about it. He was a Jansenist by both heart and spirit. This ‘moralist’ destroyed the social world [le Monde]: the court, courtiers, royal power. To official knowledge, the Cartesian (state) logos, he opposed the asceticism of a non-knowledge full of bitter clarity. Nietzsche both read and reflected on La Rochefoucauld’s Maxims. Not only did he know them but he imitated them. The aphorisms of Human, All Too Human (first volume 1877–8; second volume 1879) extend to the modern age the harsh analysis, intrepid penetration and sad knowledge of the French ‘moralist’ (who might be more properly called an ‘immoralist’). They have the same frame of mind, the same pointedness and alacrity. If Nietzsche revealed the libido dominandi, self-love as ambition and struggle for power, it was to denounce it down to its roots. The Protestantism of this son of a pastor drew nourishment and strength from a Jansenism diverted from its aim and its meaning, and soon turned in protest against those who destroy the ‘world’ but do not know what to do with the debris.

So much for the ‘sad science’. As for The Gay Science (1881–2), it has a close origin and a (dialectically) opposite meaning.20 Outside of Greco-Roman logos (logic and law) and Judeo-Christian morality (the hatred of pleasure, enjoyment viewed as sin and defilement), what did the West invent? A madness that gives meaning to actions and things: individual love, mad love, absolute love. But the West misunderstood, ignored and crushed the best that it had. Southern French civilization – that of the Midi and King Sun – which assimilated images, metaphors and concepts from the Arabs of Andalusia as well as from Celtic legends,21 brought courtship into love, which did not just mean respect for the beloved ‘being’ (the individual, the person), escaping the ancient status of beautiful object, but the sharing of pleasure. The ‘gay science’ was not simply a rhetoric of love, or a way of assembling words. It was the art of living in and through love: the art of joy and amorous pleasure. The lover, in the act of love, honours his lady. He serves her instead of using her for his sexual need. Respect for the beloved being – the beautiful woman – not only meant refusing to consider her as an object, not only submitting to her will and even her caprices, but also giving her control of physical pleasure. Courtly and absolute love proclaimed itself above ambition and power, beyond the will to power. The ‘libido sentiendi’ was redeemed, purified by passion. Desire was once again infinite, as it no longer had a finite object before it but a divine being, ‘deus in terris’: beautiful, active, sentient and conscious. The ‘gay science’ supersedes sin and redemption. It rediscovers the innocence of the body and great health. It contains a deeper understanding [connaissance] than the bitterness of critical analysis, and ‘truer’ than the ‘pure’ knowledge of the learned. Better than work, and more than knowledge, it gives meaning and value to events, actions, things. It is a constant festival.

Nietzsche brought together ‘gay science’ and ‘bitter science’, superseding the one with the other, subordinating lucidity to joy22 without losing it, and likewise knowing [connaître] to living. From their conflictual unity he sought a third term that he believed would arise: a poetic life of the flesh to transcend both the ‘sad science’ and the ‘gay science’.

Living and lived experience forcefully reassert themselves, with violence if need be. Against whom and against what? Against the coldest of cold monsters, the state. Against sad (conceptual) knowledge, against oppressive and repressive violence. Against the everyday, against unacceptable ‘reality’. Against labour and the division of labour and the production of things. Against social morality and constraints, those of a society without civilization that seeks to perpetuate itself by any means. Around 1885, shortly after Marx had died, Nietzsche the poet, Nietzsche the megalomaniac, cried out his anguish and his joy. He wanted to save the world and Europe from the barbarism they were falling into. Western society, that of logos (Greco-Roman: logic and law) and morality (Judeo-Christian: Puritanism), had become monstrous beyond belief, beyond all measure. Production for destruction, making children for wars, accumulating knowledge to dominate peoples, Nietzsche saw these absurdities in Germany under the sign of reason. He sensed, denounced and stigmatized the fundamental error, philosophically consecrated and legitimized by Hegel: the conjunction and fusion of knowledge and authority, abstract cognition and power, in the state and the state model of modern society. Today, he would see the destruction of nature (both outside and within ‘man’) as a manifestation of the will to power in all its horror, rather than its negation. And the same with the potential self-destruction of the human species (nuclear danger, etc.).

The West had tried out its values, in an immense assertion: logic, law, state (Hegel), work and production (Marx). The result tended to prove the failure of the human race. The reverse and counterpart of this colossal assertion was a hidden nihilism and a malevolence pertaining to pathology. European nihilism was not the product of critical thought, but of its ineffectiveness. It did not come from the rejection of history, nation, homeland, but from the defeats of history. Its secret, its enigma? They lie in the assertion itself, that of logos, an assertion that appears full yet reveals its emptiness.

Did Nietzsche ignore work, industry, the working class, capitalism and the bourgeoisie? He speaks little of these directly. He speaks of them only through the critique of culture and knowledge. If he dismisses them from his field, it is because in his view none of these terms, none of these ‘realities’, contributes a perspective other than nihilistic. Where Hegelianism had seen the triumph of reason, where Marx saw the conditions of a different society, Nietzsche perceived only a ‘reality’ that he did not strive to recognize at such, except to refute and reject it. For it would tumble into mud and blood.

Should Nietzsche be defined as anarchistic? Yes and no. Yes, as he rejects en bloc the ‘real’ and knowledge of the real considered as higher reality. Yes, as with him subversion is distinguished from revolution. No, as he has nothing in common with Stirner or Bakunin, who define themselves by a consciousness, a knowledge (not political in the case of the former, basically political with the latter). Anarchists remain on the ground of the ‘real’: of what and whom they combat. They want to see and possess a ‘property’, albeit unique, or expropriate those who possess ‘reality’.

Nietzsche wanted to supersede the real – transcend it – by poetry, appealing to carnal depths. Did he struggle for the oppressed? No. According to him, the oppressed have often, if not always, lived better, in other words, more intensely, more ardently, than their oppressors: they sang, they danced, they cried out their pain and their fury, even when subject to the ‘values’ of their conquerors. In their own way, they invented. What? Not what would bring down their masters and overturn the situation, but something else, closer to Dionysus, god and myth of the earth, of the vanquished, of the oppressed (women, slaves, peasants, etc.).

For Nietzsche there is thus an inaugural act: redemption, supersession. Renouncing the will to power after having experienced it, thus renouncing the political acts by which oppression and exploitation are maintained – this is how the initial act is placed in perspective. Will to live? This remains derisory if one (the ‘subject’) sticks to an intuition, an intention – which dismisses voluntarist and vitalist philosophy: Schopenhauer, Stirner and many others. Classical tragedy marked the place of redemption; it repeated the sacrifice of the hero to show how his fate is accomplished and what leads him to his loss; it redeemed the spectator-actor from the obscure wish expressed in wanting power. As a popular festival, it opened up new possibilities: in Greece, urban life and rational law supplanted custom. Music offers the example of an ever prodigious metamorphosis, transforming anguish and desire into joy, in the course of a purification deeper than Aristotelian ‘catharsis’. It creates meaning. The ‘subject’? This preoccupation of the philosophers proves derisory. There is no other subject than the body; but the body has its depth, and music is born from it and returns to it, with its sounds more luminous than light that speaks only to the gaze.

On the basis of this exaltation of art, myths and religions are to be interpreted instead of falling into derision (superstition). Myths and religions sought redemption, but missed the real aim as they served as masks for the will to power, generating practices (rites) and institutions (churches). If religions are understood and interpreted, the causes of decadence are found in them, particularly in the West where Judeo-Christianity generated capitalism and the bourgeoisie, phenomena that were derivative but that aggravated their causes.

Nietzschean overcoming (Überwinden) differs radically from Hegelian and Marxian Aufheben. It does not preserve anything, it does not carry its antecedents and preconditions to a higher level. It casts them into nothingness. Subversive rather than revolutionary, Überwinden overcomes by destroying, or rather by leading to its self-destruction that which it replaces. This is how Nietzsche sought to overcome both the European assertion of logos and its opposite obverse side, nihilism. Is it necessary to add that this heroic struggle against Judeo-Christian nihilism on behalf of and through carnal life has nothing in common with hedonism? There is a triad (three terms), but in the course of the struggle what is born casts the other terms into nothingness (sends them zu Grunde, as Heidegger would say), with the result that they then appear as ‘foundations’, depths. Dialectical? Yes, but radically different from either the Hegelian or the Marxist dialectic. By the role, the import, the meaning of the negative. By the intensity of the tragic.

The superhuman? This is born therefore from the destruction and self-destruction of all that exists under the name of ‘human’. It is the possible-impossible par excellence, as already implied by the initial and initiating redemption: rejection of the will to power, the gay science and joyous pessimism. As for what should be (Sollen), this is an imperative of living rather than morality. A distant possibility? No! So close to everyone that nothing is able to grasp it, the superhuman resides in the body (cf. what Zarathustra says of ‘those who have contempt for the body’). This body, rich in unknown virtualities, unfurls some of its powers in art: the eye and the gaze in painting, touch in sculpture, the ear in music, speech in language and poetry. The total body, in a conjuncture that favours it, is unfurled in theatre and architecture, music and dance. If this total body deploys all its possibilities, then the superhuman penetrates into the ‘real’ by metamorphosing it. As in poetry and music. Not without certain ordeals, such as the terrifying idea of eternal recurrence: the reproduction of the past, absolute repetition or the absolute of repetition, chance and necessity dizzily united …

7) Do we now, in the second half of the twentieth century, possess all the elements of a vast confrontation, all the pieces of a great trial (in which all that remains is to denote accusers and accused, witnesses, judges, lawyers)? No. The files are incomplete, by a long way.

If we examine the great ‘visions’ or ‘conceptions’ of the world (understanding by this, in a rather imprecise way, theologies and theogonies, theosophies, theodicies, metaphysics and philosophies, representations and ideologies), we perceive that they put to work a small number of ‘principles’: one, two or three. Rarely more.23 The sacred numbers include seven, ten, twelve and thirteen. Philosophico-metaphysical principles are limited to the One, the Double, and the Triad.

Do the most vigorously and rigorously unitary conceptions have their birthplace in the East? Very likely. Hegel already thought this in his Philosophy of History.24 Are their preconditions revealed by an ‘Asiatic mode of production’, incompletely defined by Marx, which according to him differed from the Western modes of production in terms of the role of the state, cities and the sovereign, as well as in its social base (stable agricultural communities)? With the result that the entire mental and social space, agricultural and urban, was organized according to a single law. Whatever the case, immanent (in nature, the palpable) or transcendent (being or spirit), the One asserts itself as absolute principle in several conceptions of the world. Many others accept two principles, generally in struggle: the male and female principles, or goodness and evil, good people and bad, light and darkness. These dualist (binary) conceptions received their most elaborate expression in Manichaeism. Almost everywhere they draw on the magical and ritual content of popular religion. The Mediterranean basin and the Middle East seem to have been the birthplaces of this dualism, or at least its places of predilection. Is its ‘precondition’ the conflictual relationship between sea and land, plain and mountain, the settled and the nomadic? Perhaps, but it does not matter. Here we shall emphasize the differences between conceptions of the world, leaving aside their history.

The European West seems committed to triadic or trinitarian thought. And from a very early date, if we believe the research of pre-historians and anthropologists. As early as the establishment of a stable agriculture and settled villages, with the great migrations that unfurled across Europe for many centuries. The Greeks already thought in triads: chance, will, determinism. It was in the West that the Christian doctrine of the Trinity took shape, shedding unitary and dualist doctrines (respectively monophysitism and Manichaeism, the latter still being influential in the Middle Ages, as with the Cathars). Why? In what conditions? Perhaps because of the triadic structure of agrarian communities (houses and gardens, arable land in private ownership, pasture and forest in collective possession). Or perhaps due to the process of their origin: the formation of towns on an already developed agricultural basis, so that the town appeared as a higher unity, combining villages and hamlets, familiar places with those distant and thereby foreign. Or again, did this threefold model have its origin in Euclidian geometry and the theory of three-dimensional space (though it seems to pre-exist this, and to develop outside of science). Why not look for the reasons and causes of the dominant representations in social or mental space? We only raise this question here in passing.25

An underground current runs through Christianity, deeper and more hidden than Augustinianism, because it’s more heretical. It could be compared with a water table that irrigates the roots of trees, surfaces in springs and fills wells. Joachim di Fiore’s ‘eternal gospel’ very probably owes its form to Abelard as much as to its attributed author. Removed from their mysterious and mystical substantiality, their eternity, they form part of ‘reality’ and historicity. The Father? This is nature and its wonders; the infinite and terrible fertile power in which are dimly discerned creation and the created, consciousness and unconsciousness, suffering and pleasure, life and death. Hardship is not added to natural existence, it is inherent to it. The Son, the word, is not eternally coextensive with the paternal substance but emerges from it, is born from it in time: language, consciousness, cognition, coincide with the birth and growth of the Son. In the course of his rise, knowledge cannot fail to acquire self-confidence; this faith goes hand in hand with consciousness and its troubled certainty, conquered over doubt. The word believed it would save the world. It failed. Knowledge is not enough for redemption – neither is the suffering of the unhappy consciousness. Not only did Christ (the word) die in vain, but his death enabled the worst of powers to establish itself, the Church that celebrates the death of the word by killing it each day: killing thought. In order for redemption to be accomplished, the Spirit, the third term of the triad, a triad eternal and temporal, immanent and transcendent, has to be embodied and turn the world upside down. The Spirit is subversive or is nothing. It is embodied in heretics, rebels, the pure who struggle against impurity. It brings with it revolt and joy. Only the spirit is life and light.

Joachim’s eternal gospel divides time into three periods: the law, faith and joy. The law belongs to the Father and comes from him: the harsh law of nature and the power that extends this. Faith belongs to the word, the Son, with its corollaries of hope and charity. The Spirit brings joy, presence and communication, absolute love and perfect light. But also struggle, adventure, subversion, thus a violence against violence …

Misunderstood by the customary history of philosophy, as by that of society, this triadic schema had an inestimable import. We should note that it has, as a schema of reality and model of thought, far greater flexibility than a binary or unitary one. It contains rhythms; it corresponds to processes. It cuts across Cartesian thought, in which the divine infinite embraces the two modes of existence of the finite, extension and thought. It triumphs in Hegel. What is Hegelianism? An interweaving of triads, emitted and recaptured by the third higher term, the Idea (the Spirit).

First triad: nature, history, concept. Second triad, implicit and explanatory: thesis or assertion; negation or antithesis; synthesis or positive (affirmative) supersession. Third triad: need, work, enjoyment, or rather, satisfaction. Fourth: the master, the slave, the victory of the slave over the master, a victory that transforms him into the master’s superior, superseding him. Fifth: prehistory, history, post-history. And so on. As for Marx, his triadic schema modifies but preserves the Hegelian schema, taking it (according to Marx and Engels) to a higher level – affirmation, negation, negation of the negation – which accentuates the role of the negative.26 The developed communism of the future restores primitive communism but with ‘the full wealth of development’. Private property of the means of production supplanted the collective possession of these means (the land), but will give way to a social possession and management, hence collectives and automatic machines. Even Marx presents a bourgeois Holy Trinity: capital, land, labour (profit, rent, wages). And so on.

Oddly enough, the positivism that opposed any philosophical speculation adopted the triadic schema. According to Auguste Comte and his famous law of three stages, the metaphysical age followed on from the theological age, and the scientific age will replace it.

As for Nietzsche, if we accept that he identifies himself with his spokesman Zarathustra, he also adopts the triadic schema: ‘Three metamorphoses of the spirit do I designate to you: how the spirit becomes a camel, the camel a lion, and the lion at last a child.’ The camel demands the heaviest task, the most onerous law. The lion seeks to win its freedom and assert itself, by finding itself, by becoming capable of creating; it has faith in itself and in its future. The child is innocent and forgotten, a beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel: joy. Zarathustra said this while staying in a town called The Pied Cow. Did Nietzsche have in mind the quest for the Grail (the absolute), and Percival (Parsifal) whose story tells of his youth, purity and even simplicity of spirit? After Merlin (divine/diabolical) and Lancelot (man and superhuman) comes the Spirit-child.

Why not apply to our own triad Hegel-Marx-Nietzsche the same triadic model? Hegel would be the Father, the law; Marx, the Son and faith; Nietzsche, the Spirit and joy! Such an application does not hide its parodic intention …

Why this reflection or retrospection on triads? Because nothing guarantees the eternity of this model. Will it not also suffer obsolescence, exhaust itself? Should we today, after detailed examination of the triads, not reject this schema and supersede it, either by Aufheben or by Überwinden? Or else leave it only a share, perhaps the sacred/accursed share, of ‘our’ reality or our understanding?

Does this appreciation (also for the moment at the stage of a tactical hypothesis) lead to a return, recourse to the substantialist (absolute unity) or binary model (formal oppositions, non-dialectical contrasts and dualities)? This is neither obvious nor probable. More likely we shall have to adopt a different route: an approach that takes account of a greater number of moments and elements, levels and dimensions, in brief, a multidimensional thought. Will this maintain, in contrast, that thought, by taking account of greater numbers, loses itself in too great a number of parameters, variables, dimensions and flows? Not necessarily!

8) The ensemble of categorical assertions posited by Western logos is surrounded by a network of problems. Among these, that of cognition emerges and deepens, abyss and mountain. Philosophy raised it in the late eighteenth century, and from then on it formed part of the theoretical situation in Europe. Previously, in Cartesian thought, in the critical project associated with the Encyclopédie that arose in France, and in the empiricism and positive science that emerged in England, no doubt appeared as far as knowledge was concerned. The critique of religion and the political regime was pursued in the name of cognition. Logos was questioned but was not itself put in question.

The scene changed with Kant’s critical philosophy. ‘What is it to know [Qu’est-ce que connaître]’? This simple question ravaged questioning thought. From this time, it would pursue its path no longer by seeking the absolute (the mythic Grail), but instead the answer to the question of understanding. The horizon changed. This ravaged thought would hesitate between rationalism and ‘classical’ humanism, a humanism that received its formulation from Goethe, and romanticism, itself dual: either reactive or revolutionary.

Unfortunately, philosophy and professional philosophers restricted the problematic of understanding to make it more precise, so that it would belong to their ‘discipline’ which was tending to become a speciality. They saw science as an incontestable process, an activity both sufficient and necessary. A reduction that reduced philosophy to epistemology, a meticulous sorting between acquired knowledge and uncertain representations. From Kant on, philosophy put the problem of understanding as follows: ‘Where are the limits of knowledge, either provisional or definitive? How can these markers be crossed? How can we know (connaître) more and better: more knowledge and more certain knowledge …’

Philosophy like this sidestepped the wider problem, the real question of understanding: ‘Knowledge is necessary, but is it sufficient?’ What is cognition worth, not in terms of results – conceptions, methods, theories – but as activity? Various responses were immediately proposed: the sufficiency of knowledge was countered by the notion of a necessary and insufficient knowledge, and that of a necessary non-knowledge: cognition was referred beyond or below itself, to intuition, ‘learned ignorance’, or pure and simple faith.

Who formulated the problematic of understanding in its full scope? Goethe. Not in Werther or Wilhelm Meister,27 but in Faust, in other words, a tragic play rather than a novel.

This play (hardly stageable, particularly the second part) opposes living to cognition. Faust, who knows all that could be known in his day, belatedly perceives that he has failed to live. For his happiness and unhappiness, he is visited by the demonic principle: the absolute Other, the accursed of God, who knows what Faust does not know, who possesses the secret of living: passion, delirium, madness, crime, in a word, evil (sin). Mephistopheles (with the authorization of his hierarchical superior, the eternal Father) allows Faust to pass through the ordeals of living after having undergone those of knowing. He leads him to Gretchen, the woman still passive, beauty (the beautiful object), but able to suffer and complain, and then to Helen, the active woman, still more lovely, but more ungraspable. The old triptych God–man–devil is joined by a fourth character: woman. She differs equally from the eternal virgin and the eternal mother. She is duplicated: victim and servant of sensual pleasure (Gretchen); queen of beauty, joy and delight (Helen). The eternal feminine is revealed only by way of initiation and ordeal.

To the great question that opens like an abyss on the path of ‘modern man’, Goethe gives only a poetic response: all that happens is only symbol, hieroglyph, and only the eternal feminine calls and shows the way of redemption. This is how the great Western idea pursues its course, that of absolute love as a counterpoint to logos. This great image runs right through the West, from the medieval romances down to Le Grand Meaulnes, where it dissolves in the pallid moonlight of the beautiful soul. Unless it rebounds …

Still in Goethe’s lifetime, Hegel divinized knowledge. For him, the negative places itself in the service of positivity: absolute knowledge. And we could interpret the demonic in Goethe (Mephistopheles) as an accentuation of the negative, given that its role remains ambiguous. For Hegel, then, God is the concept, the concept is identified with divinity. The concept of history and the history of the concept coincide. From nature emerges logos, the word: then nature and word (science and consciousness, language and logic) unite in the recovered spirit, absolute spirit. God-knowledge and history converge in the state. Absolute spirit, logos as principle and end, is ultimately defined as a philosophical trinity: concept (father), becoming (son), state (spirit). And Kierkegaard was not wrong to rail sarcastically at the speculative Good Friday by which the god in three persons incarnated in history climbed the Golgotha of dialectical ordeals to reach the glory of the last judgement (as pronounced by the philosopher).

With Hegel dead, Hegelianism disintegrated. What a strange situation European thought found itself in after Hegel and Goethe, after Kant and Schopenhauer! At first with the Young Hegelians, then after them, Marx hesitated between knowing and acting. He retained the project of constructing an imprescriptible knowledge, resistant to all refutation and reaching the essence of society (bourgeois, capitalist), but he took up the Promethean-Faustian formula: ‘In the beginning was the deed.’ He maintained the Hegelian ideas of a rationality underlying history, a philosophico-scientific certitude inherent to the analysis of practice, a finality subordinating causality and necessity. At the same time, he hesitated before the rationality that in this schema was immanent to existing society and reality. How long would the bourgeoisie survive? Would it exhaust its inherent rationality? Did this reason itself have to be broken, along with the state and property relations? Would the bourgeoisie continue its historic mission for a long time, the growth of the productive forces until the inevitable qualitative leap? Where were the internal limits of capitalism? If there is a rationality everywhere, it is also to be found in this society, which is easily qualified as absurd on the grounds of its injustice and inhumanity.

Marx posited a meaning of becoming, of history, without demonstrating it; he accepted Hegelian (Western) logos without subjecting it to a fundamental critique. Hegel’s still-theological hypothesis passed through the sieve (the ‘break’) in Marx’s thought. No more than Hegel did Marx question the origin of Western rationality, its genesis or genealogy: Judeo-Christianity, Greco-Latin thought, industry and technology. Marx was content with an attenuation of Hegelian theology (theodicy) and the epic of the Idea. Sometimes Marx and Engels came up against some conceptions that were irreducible to their schematization; for example, logic and law. Why had logic (born in Greece) continued across the Western societies and their modes of production? What relationship was there between ideologies and the dialectic? As for law, elaborated in Rome, this lasted until its renascence in the bourgeois-democratic revolution, with the Napoleonic code civil. Accordingly, the social transition to communism would not be able to do without law and laws, with the result that the triadic schema – from unconscious customs under primitive communism, through law in the course of history, to conscious custom within ‘developed communism’ – remains abstract. Equally, Marx was unable to say much about the future communist society, other than that the long transition would be punctuated by ends: end of capitalism by revolution; end of labour by automation; end of law by custom; end of state, nation, homeland, working class, bourgeoisie, a separate economy and a dominant polity, etc. Nietzsche would add to this list: the death of God and man.