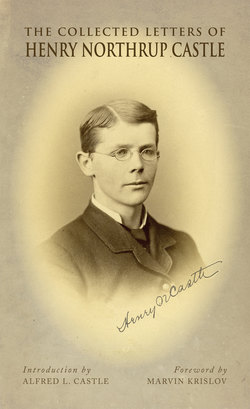

Читать книгу The Collected Letters of Henry Northrup Castle - Henry Northrup Castle - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPARIS, Sunday, Aug. 31, 1879.

MY DEAR MOTHER,

I write you this in the hope that it will reach you before the steamer of September 4th comes bearing to you Jim and Helen, but no Henry and no Carrie. That is, if the fates of men and of gods don’t forbid. Yes, Mother, Carrie is to stay and prosecute her music, as it were, and I to study. The explanation of my course (Carrie’s requires none) you will naturally be anxious to hear, and so, too, I presume, will the home folks. So, without further ado, I shall plunge into the subject, and if I get beyond my depth, as I probably shall, you may attribute it to the violence of the plunge. And first, why I—or we—had decided that I should come home. The reason is simply this. Our tickets for the steamer of Sept. 4th had to be handed in if we intended to return on that date. If this was not done we would probably be unable to get places later, as the boat was going to be crowded. Not handing in the ticket, then, was equivalent to a decision of the whole question—a decision to stay and study in Paris. The problem thus forced upon us, what could we do? Studying in Paris was (but is not now) a “glittering generality.” We did not know a solitary thing about it. Was there a single school of my grade in Paris? For any knowledge of ours to the contrary, the answer might have been no. If there were, could I study what I wanted, or would I be put through a course? When would the term begin? How long would it take me to learn French? What was the method of instruction pursued? and would I have to pass through the fiery ordeal of an examination? All these questions met with complete blankness for answer. Thus, a decision to stay would have been a “leap in the dark,” and all on the strength of an indefinite Parisian reputation. Besides, I was not sure that in any case it would be desirable to remain. Can you wonder, then, that my ticket went in for Sept. 4th. But why did I change my mind, is the next question? Well, all through the trip I had a great desire to stay over a little while and see more of the great cities of Paris and London. It seemed a great pity to come all the way over here, and then see so little of them. I might never have another opportunity. Then I wanted, too, some little time to rest and digest this tour, and not to rush right off to Oberlin into studying again. But the thing appeared impossible, as I was determined not to fall behind my class a single term. And so the question became, stay for aye, or go at once. And as no other conclusion seemed wise, the decision was—Go! Such, then, being my state of mind, I arrived at Paris Thursday August 27th in the full expectation of looking my last upon the shores of Europe on September 4th precisely. Naturally enough, I was carried away by the great city, and wished I were going to stay. Then Carrie decided to pitch her tent here, which increased my desire. I thought I could study French, and read French History, and learn lots about Art—and Paris. I thought, too, I could make up while here one or two of the studies of the Fall term at 0., and if I was successful at my French, it would not be necessary for me to take it at 0., and so I would not fall behind at all—a comforting and encouraging conclusion. Then Jim comes into the case, and fails to see the especial use of my staying unless I stay to study in the schools here. I tell him I would, but I don’t know anything about their old schools. But I am seized with a desire to do so if feasible. Then our conductor comes along, and we learn that the question must be decided at once. I rush off immediately and apostrophize Mr. Gray in search of information. He gives it, and it is satisfactory. I must, he says, go into a school for English boys for three months, and learn the French language. I may then be examined to enter the Lyceum. This decides me. I will at least (so it appears) learn French enough to save my two terms at Oberlin, and by taking one or two studies besides, I am certainly even with, if not ahead of, my friends at O. So whether at the end of that term I return, or stay and try for the Lyceum, I don’t drop behind my class. And so, Mother, there lies the solution of the whole problem, and I accepted it, and decided to stay. Since then I have learned that the Lyceum opens Oct. 6th, and of course if I can enter then, so much the better, though I don’t think I can learn French in five weeks. I suppose, unless the family object, and the information I may acquire in future prove unsatisfactory, that I shall stay a year. But only a year. I have no thought of staying longer, even should you be perfectly willing. When the folks at home hear that I expect to remain, if my ticket can be fixed (which I don’t know yet by any means), I think I hear the cry of disapproval which will at once arise. Brother Will will say that he thinks it will be decidedly injurious to me; George will ditto, or else be in doubt; and in any case there will be some discussion, I think, if my prospects for the future can arouse as much interest as that. At any rate the thing may attract some letters to me, and that part wont be disagreeable. But remember I don’t expect to stay long enough to have my character and mental tastes and habits moulded after French models. You will say at home that a man ought to be educated in the country in which he expects to live, and I suppose that may be true, but this will only be a small part of my education, and it is a splendid chance to spend some time in such a great art centre. I will try to learn a great deal about art, and I do want an opportunity to look at pictures at my leisure, and not be rushed through them as I have been. It seems to me almost a crime to study in such a place as O. A fine sunrise and sunset, grand and beautiful scenery, seem an important part of one’s education. In Paris, at least, I will be in a great and beautiful city, and will enjoy all the collateral advantages of the place, and can at least feel that I am on historic ground. I can say for myself, in conclusion, that in staying I have been moved only by the consideration of my own best good, educational and otherwise, and that any such subsidiary thing as the pleasure to be derived has been entirely overlooked. I may also say that in making the decision I have acted by the advice, and in accordance with the wishes of the family here, and, according to my light, have acted for the best. Father, I will study hard, and try to master the French. And now, Mother, don’t you worry about me; I shall try to be a good boy. Remember what you are always saying: —” Never mind, it will all come right.” And so it will. The only thing that I mind is not seeing you again. But if I don’t stay a year, I will see you before you go home, I hope. In any case, you know my dream has been for more than a year to make a long visit home before finishing my course, and if Father’s ship comes in, I shall do it, if he is willing: During my stay here I shall be homesick for Oberlin many times, I expect; but never mind, I shall see it again. Oh, how glad I was to hear that Lucius is better. Tell the dear boy that I hope he will soon be well and strong. Give my love to dear Aunt Mary and Uncle, and tell her not to work too hard. If she cares anything about it she will see me graduate at old O. yet, and I will hire a carriage to take her to the first church to hear my last speech.

With love,

HENRY.

HOTEL LEGER, No. 2 RUE THENARD,

PARIS, Sunday, Sept. 7, ’79.

MY DEAR MOTHER,

We are nicely settled here, at the address which you see at the head of this letter, in all respects a nice situation. We were entitled to two day’s board and lodging at the Hotel D’Albe instead of that which we were to receive from Henry Gaze & Son at London, before moving down here. So after Jim and Helen left us, Tuesday night, we stayed at the hotel till Wed. evening, and then departed for these diggings, where we have remained ever since. Dear Mother, I can never remember where my last letter to you left off, and so if I want to give you an account of my adventures, I never know where to begin, and consequently never do begin, which doesn’t bear so hard upon me as upon the poor unfortunate who has to read my effusions. But let me sail in someway, and perhaps I will tell you something you don’t know, and perhaps I wont. And to begin at last, the first fact that comes to mind, and impresses itself as interesting is that our grand European Tour is ended. The great affair which I looked forward to so, and which seemed a magnificent impossibility, is through with. I have done what I scarcely ever dared to hope to do—seen Europe; or, at least, have been through Europe and tried to see it. Another and a second fact is that it hasn’t done me the good that others may have hoped and that it ought to have done. And this will make Father feel bad. But it seems to me that I got as much and more good than most of the section. A third fact is that I don’t deserve to go to Europe. And this I feel most painfully. Why, here I have been in Europe two months, and haven’t learned what the chancel of a cathedral is. I had no business to stir out of 34 West College. I haven’t improved my time and opportunities well; I have not read at any and every chance that came along, and been attentive and observing enough; I haven’t appreciated the magnificent advantages of the situation, and taken advantage of it as I should have. In short, comparatively speaking, I have gone through Europe with eyes and ears closed. Every time Father spoke in his letters about how we would or ought to get so much good from the trip (and that was every time he wrote), I felt a little twinge because of these facts. Now, I know it will cause Father pain and disappointment to hear all this, and well it may, for he will feel that he has wasted $500 on me. But I don’t think it is quite as bad as that. I know that a trip like this ought to do me a world of good. I don’t think it has done me that good, and so I know there is something wrong about it, but just where I have failed I can’t tell, except, of course, that I should have learned a great deal about art and architecture, and acquired a great deal of general information, and read a great deal, none of which things I have done. But, my goodness, that’s enough. When I read that sentence over I see it counts up fearfully. O dear! A fourth fact is that the trip has done me some good, I think, notwithstanding this discouraging aspect of affairs. And a fifth and last fact is that it has not done me the harm I feared. I thought that to go to Europe when I knew so little, to tread upon historic ground and not even know that it was historic; to see ancient cities, which, standing upon their intrinsic merits as cities, are rather seedy, and not know what makes them interesting, nay immortal, what great deeds made them holy ground, &c., &c., &c.; to do all this, I say, would do me more harm than good; and, I think, perhaps some others shared my opinion. But I don’t think it has. To be sure the halo and gloss and magic which hung about the word Europe has been dispelled (the same magic that made me think when a youngster that the United States was of course a thousand times better a place than the islands) for I have discovered that life is life the world over, and that Europe is prosaic and real, as well as any other country. But in return for the valueless conception I have of course lost for ever, I receive one based upon the solid merits of the case. So I feel comforted in regard to that. In regard to the Section, you know that we, or at least I have been much disappointed as to the people with whom we were to travel. I expected that they would be fearfully cultured, so aristocratic and nice, and “hightoned,” that I wouldn’t dare to go within six blocks of them. But that, I need hardly say, has not been the case. As a company, they have been chiefly noticeable for ignorance and lack of culture. But what do I care? The fact that they were such would spoil many people’s enjoyment of the trip. Mine it does not even affect. Isn’t that fortunate? Even odious people are matters of indifference to me, as long as they leave me alone. I came to Europe to see itself and not them. But never mind. When I parted from them at Paris, I was actually sorry to see them go—I suppose because I had had such pleasant times in their company. When they were all gone, we six or eight who were left went into the hotel parlor, and we felt lonely; at least, I know I did. There seemed to be nobody around. The place was deserted. The next night Jim and Helen took up their departure. And then we felt alone indeed. Who can tell what a day or an hour may bring forth? When they left us, less than a week ago, I did not expect to see Jim for a year, and Helen nobody knows how long. But now, if things go smoothly, I suppose we shall see them both again and yourself in less than a month. And that brings me at last to the subject on account of which this letter is written,—our return home. We were all settled here, with our rooms taken for a month, when the home letters came, saying we could not stay. We have telegraphed to London to see if we can obtain places on the steamer of the 18th, and shall leave then if possible. If impossible, then by the first on which we can get passage. I am very glad and very sorry to return. Glad, because inclination takes me home. Sorry because I feel that it is best for me to stay. O dear, if we only knew what takes us home. Is it expense? We can live here cheaper than we do in Oberlin. Carrie’s tuition in the Conservatory would be—nothing. It must be that we are in danger of being thrown on our own resources, and that, I suppose, had better be in America than here. I had commenced to study French, and had made a very little progress. It seems a pity to go away, and see so little of Paris and London. And then, if we return, all the time that we have stayed over is sheer lost time. I will have just so much more work to make up. I should have been dreadfully lonely and homesick in Paris, but it will be just as bad, if not worse in O. I wish Metcalf would room with me. Love to Auntie and Uncle, and yourself a good share.

HENRY.

OBERLIN, O., Sunday, October 5th, ’79.

DEAR SISTERS, CARRIE AND HELEN,

Both of your letters were duly received, and were very welcome. I have been so busy since I arrived that I have put off writing and even acknowledging your letters until Sunday, when I would have a little time. Hattie and I had a very pleasant trip together, and arrived at O. on time I believe. Our sleeping berths were adjoining, and a gentleman who had the one under me kindly offered to exchange with Hattie, so we had a gay old time. Our train was a very long one, and when I got off at O., ours being the rear car, I had quite a little walk up to the depot. I kept my eyes wide open, for I thought possibly, as Carrie suggested, that accident might have brought some of my friends down to the train. I was quite certain that I recognised Fred’s hat and the back of his head, sailing off with one of his friends; but I didn’t sing out, for I wasn’t certain it was he. But it was, I afterwards found. When I got up on the depot, I saw French’s hat and the back of his head and coat. I rushed up, and addressing my remarks to his back, said that this was somebody I knew. He turned round, and gave a yell, and immediately I found myself launched among a crowd of friends and acquaintances. There was French, Metcalf, half-a-dozen other classmates, and Prof. White. George Mead was there, too. Immediately they marched me off, French exhorting me to come up to his house, and telling me that my bed wasn’t made. We went up to Uncle’s and found lights all out and family all in bed earlier than usual. After making considerable noise on the porch, and hearing, laughter in Auntie’s and Uncle’s room (now Jennie Harrold’s), we concluded not to ring the bell, and sailed off to French’s for the night, where Metcalf rooms with his cousin. The latter was away at Elyria, and so I slept with M. Came up in the morning, and surprised the family. Breakfasted with Auntie. Dined with Mrs. Harvey. Those young ladies are fearful, and my progress with them is slow. But I don’t quail so much now. Uncle William is here, and Auntie had me to supper with them last night. Has invited me again for to-night. I see almost nothing of Auntie, never seeing her unless I go down on purpose for a visit. Tell Mother not to hurry herself for me, but to stay in N. Y. as long as she wants. And, Carrie, don’t let me affect your plans at all. I don’t mind being here alone. I am not nervous at all nights, and the fear of being so has always been the cause of some of my objections to being alone. Besides, perhaps I shant stay here. I don’t want to, though I suppose I must. The place is haunted). and I cannot bear it. It is like living in a grave. But no more of that. I have felt very strange, and like a fish out of water since I have been here. I didn’t open the closet door in the front room here until this morning. That in the back room I haven’t opened at all. I haven’t moved or touched a single chair in either room, except the one I sit in, I have moved up to the table. I haven’t unpacked my valise, nor opened my trunk. And have only very lately opened the table drawers. I seem like a person in a dream. When I did open my drawer, I found a letter for me there from Walter Frear. Soon after yours, Helen came. Then one from Miss Berry, and then Carrie’s and Jim’s postal. So I have been favoured in the matter of letters. I fear I wont have time to answer them all, and I don’t feel like writing either. Give my love to Mother and all the folks, and my aloha to Julia when you happen to be writing, please. Ask Mother whether I shall go to hear Joseph Cooke. He lectures here on Mormonism next Friday night. If you answer at once there will be time for me to hear before then. So be sure and do it.

Yours truly,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, O., October 9, ’79.

MY DEAR BROTHER JIM, AND FAMILY IN GENERAL,—CARRIE, HELEN, MOTHER,

I take up my pen with considerable hesitation to attack a subject which I likewise dubiously approach. I mean, in brief, that I should like mighty well to go home with you, or on the steamer next afterward, i.e., the December steamer. This may be, and probably is, a wild dream—a hopeless chimera. If so, all that is necessary is that you should tell me so. Of course there are endless difficulties in the way of the accomplishment of this fancy of mine. In the first place, as a fundamental thing, I must convince all of you members of the family that my plan, in the first place, is not an improbable one ; I must convince you that I can and will carry it out. And so for my plan. I propose to go home first, accomplishing this term’s work here, either with you or on the steamer after. I propose to stay at the islands till next fall or until the winter term of the Sophomore year. I propose to interview my teachers here, and have them tell me just what work they are going to do during my absence as to translation, prose, grammar, &c., &c., so that I shall not suffer the usual disadvantages attending one’s taking the classics, away from the place where he eventually studies. For I shall do exactly the work done by my class during my absence, so that on my return I will meet them on an equal footing. When I get home I shall study by myself every day, accomplishing just the amount of work daily necessary to get through the term’s work prescribed for the class, or I may have a tutor for, say, an hour and a half a day for my three studies, as may seem best. If it may not seem feasible to make up such a study as University Algebra, I can easily make up something else, as French, alone. Such, in brief, is my plan. Now, as a fundamental proposition, I must convince you first that the thing is possible, practicable, and will be done, as I have planned it. And, of course, the only thing in the way, the obstacle which everybody will mention, is myself. I will (they will say) get lazy, and not study. Without the stimulus of rivalry and marks, one will get careless, and the result will be that the whole aircastle will end in smoke, like us children’s peach orchard. (Do you remember?) I freely acknowledge that such is the weakness of human nature, that such objections to a plan like the present one are not entirely groundless; but to assert them as a reason for not adopting the plan is an insult to one’s manhood. Justly, perhaps. Perhaps that is putting it too strong, but at least it is to say that one is without moral stamina, and utterly destitute of strength of character. Such reasoning will do for village school children, who study because they are made to; but, really, to assert that an intelligent thinking student, who studies for the sake of an education, will not and cannot study without the whip and spur, is rather bad. It is a shameful fact that. more of us do not, to be sure, and I am weak and failing more than any; but systematic loafing is a violation of conscience and principle with me now, as well as of wisdom and policy. (Q.E.D.) Second, I must prove that it will not do me any harm to thus absent myself from my class for a year. I will in the first place do just as good or better work there than here. And here it is hot, and dusty, and dry, and ugly. I am commencing to feel more and more the importance of beauty as a developing element in a man’s education. There I will have it, here I will not. There I will be happy, and here at best I will not be happy, perhaps live a negative life. So far as it will be pleasant at all, it will be so by the burying of memories, and careless, thoughtless forgetfulness; and Mother, I don’t want to forget. But if I live here I will forget. A new life will grow up and hide the old; and the old I love, and don’t want hidden. Then I am young and small still, and have never been separated from you. There I will be at home with all the folks, and next year I might return with better courage. But I am getting tired of writing, and so will condense and finish soon.

There are dozens of other better arguments that I could bring forward, but I will wait. I want to go home. I never wanted to come here at all, you know, after I heard the news. I am tired, and homesick, and lonely; not this moment, perhaps, for we live in the present, and this moment I am forgetful and unrealising. We live in the present, and as we hurry along the present becomes quickly the past, and is seen no more. At rare intervals, when one feels sick or lonely, he catches glimpses of the past, and is startled to see the many, many gravestones, all bathed in ghostly moonlight. I dread those times.

And now I come to the last great objection, like the Alps to Hannibal’s army, apparently insuperable. I mean, of course, the expense. All that I have hitherto said has been merely preliminary, to convince you first that the only obstacle was the expense; and second, that otherwise the plan is highly desirable. And about this obstacle I have nothing to say; I leave it to you. If there is any cheaper method of getting across the continent, I would gladly employ it, provided it does not take more than ten days or so to go across, and on the steamer I would almost as leave take second cabin as first, so far as mere accommodation goes, or steerage for that matter. Of course I should not enjoy the company, but any other objections, except those on the score of accommodation (and I don’t mind roughing it), merely arise from false pride, and that I want to put behind me. I suppose there is no time to communicate with Father, but I want to write to brother Will, as the next best thing. For some time I have been idly wishing that I might go home, and the idea kept taking more and more definite shape, until it suddenly occurred to me to act, and write to brother Will. But I wanted to write to you first, so I would like an immediate answer, please, which I shall anxiously await. If you approve, will you all—Jim, Carrie, Helen, Mother—write to Will, and interview him on the subject? Tell him about L.B.: I can’t. Please answer immediately.

In great haste, and with much love,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, O., Monday, Oct. 13, ’79.

MY DEAR, DEAR MOTHER,

I think that I will write you a letter now, as I have not done so for several days, and I think you may like to hear how I am getting on.

I suppose when this letter reaches you Jim and Miss White may already be married, or else just engaged in tying the knot. Just write and tell me when it occurs, will you, I shall be pleased to hear.

Cousin Roxy with her daughter was in town a few hours last night, and gave me a short call. I told her about the prospects of the family, and told her Jim’s intentions, both upon Miss White and on the Islands, and she wants you to stop there, but I don’t see how you can, and especially extended a most cordial invitation to Jim and Julia to stop and give them a call, but I don’t see how they can do that either. I suppose before this you must have received my letter about going home, and oh, how I fear decided against me. Remember, Mother, that I will joyfully go second cabin or steerage on the steamer, and emigrant train across the continent, if feasible. Then possibly I might get a position in Honolulu at which I might earn something and which would not interrupt my studies. Just such a position, in short, as I had in Will’s office. There I got $2 a week and had time to study and read. I had to open the office in the morning, sweep out and dust, stay in the office while Will was gone, and run errands. Quite likely my position was a sinecure, but anyway such an one or one with even considerably more to do at the same wages, would make me for the year one hundred dollars in; a good item to set against the terrible travelling expenses. Again, if you keep house, I will in the first place get my room for nothing, for Father would not rent it, and in the second place the only difference of expenditure by being there in the eating line would be the bare cost of the raw material: bread, butter, milk, meat, salt, and that would be very little. How much more of those would you buy? I think I may safely put it at a dollar a week. You would pay your cook the same, were I present or absent. Every expense would be the same except the raw materials. Board and room then for $1 a week. Here I pay $4, year in and year out. For the year that I would be at home then, there is a clear saving of $150: $3 a week for fifty-two weeks; another nice item to put against the terrible travelling expenses.

So you see, dear Mother, that it may not cost so much more for me to go home, after all. And now let me remind you folks that if you approve of my plan, you will besiege brother Will with letters in my favor. Be on my side with all your might, if you can conscientiously be so. I mean for all of you to write; Jim, Carrie, Helen, yourself and Julia, if you would like to. Uncle and Aunt expect to leave here Wednesday morning. But they will hope to see you, Helen, Jim and Julia in Chicago. Please give my love to all the family. I wish that I might be there at the wedding, and then again I don’t, for I should be scared half to death. What shall I do at my own, I wonder? I shall have to put it off, or perhaps I won’t have any.

With love,

HENRY.

P. S.—You spelt your “tos” and your “toos” wrong the other day. You thought you didn’t, you know.

H. N. C.

PAPAIKOU, Tuesday, January 27, ’80.

DEAR MOTHER,

My pen is rusty—persistently refuses to write, my ink is pale in all respects, and I don’t seem to be able to write decently

To face page 45

The old Home as it was in 1862.

in general. Hence, all inelegancies, &c., of this letter, you may lay to any one, or all combined, of these sufficient reasons. These deficiencies are the more inexcusable that I am just now in a position which ought to be inspiring me to strains of more than ordinary grandeur. For I am sitting on the verandah of Uncle Tenney’s house here at Papaikou listening to the music of wind and sea, combined with the melodious cackle of a persistent rooster keeping time in a sort of Runic rhyme with the shrill notes of a hen, who is discordantly announcing the advent of her daily egg. I have been having a good time up here during the week which has elapsed since I left you, though the time has passed slowly. I have been at Hilo during the greater part of it, though I came out to Papaikou with Reky and his father last week and spent a night there, getting a little accustomed to the riding over these rough roads, which shakes one up a little at first as you know. We came out at the edge of evening and I enjoyed the ride very much. The next morning we rode three or four miles up in the cane fields before returning to Hilo, during which time I made long and fierce inroads upon the soft and juicy cane, which process I have kept up ever since. I pretty nearly broke my neck though once. But I didn’t, you may be sure. My horse was at full gallop along a grassy level leading up here, when suddenly a little ditch appeared. It was impossible to avoid it, and the horse floundered right in it, slipped along and nearly fell. I found myself way over the pommel, but to my astonishment, still on the horse. What an affair it was you can imagine when I tell you that the horse got his foot over the bridle. But I am riding a horse now that wont serve me so. Yesterday, Aunt Mary came out with Ida, escorted by Ed. Tenney and I accompanied them. Ida was brought out in a comfortable chinese chair, carried by four stout kanakas, on poles. We took it easy and had quite a gay time. I have come out here to stay until I leave for the mountain excursion which will be Thursday. In the meanwhile, I am enjoying myself up here reading to Ida, and devouring sugar cane. Tell Jim that I have discovered another story by Boyesen, called The Norseman’s Pilgrimage, and I am deep in the contemplation of its mysteries with Ida. It is published in some old numbers of the Galaxy, and there are in the same magazine some articles by Coan, his friend in New York. One called A New Nation, which I should judge to be excellent and should like to read. The view from this front verandah is fine. This grassy upland, dotted with mangoes, lilacs and lauhalas, besides others whose names I do not know, stretches for half a mile down to the sea, and then the sea itself spreads out and out for miles and miles. I can see the surf breaking on the Hilo reef, and the waves dashing up in spray on the other side of the point, many miles further on. There is a delicious breeze, and things are gay in general. I think I must go saddle up my animal and take a ride now, as I have been cooped up in the house all day reading. So good-bye till we meet again, which will not be long.

With love to all the folks,

HENRY.

PAPAIKOU, Wed., Feb. II, ’80.

DEAR, DEAR MOTHER,

You understand of course why you did not hear from me last steamer. You know I was up in the mountain and couldn’t write. But now I am safely back again in a civilized community.

Please thank Helen and Julie for their kind letters. Ask Julie if she has missed her knife yet. Tell her I have it safe in my trunk, and maybe if she is a real good girl, and invites me to dinner often after she sets up housekeeping, I will let her have it again some time. Anyway I will see when I get home. I did not get home in time to go to the Volcano with Ed. Tenney, so that question is settled. If I get an opportunity can I land on Maui and go up Haleakala, and visit the Wailuku Valley when I come back. It is my best time. Thank you greatly for sending my clothes, and your careful mending of my drawers.

As to your proposition, let me say definitely this. What my views have always been they are now. If Father can afford it, I should like to go to Kauai before my return. I should also like to go to Molokai with Grandma Hitchcock. She wants sorely to go, but has no one to accompany her. If I take a position in Lewer’s & Dickson’s of course I cannot do these things. I should like to go up Konahuanui again, make an excursion to the Pali perhaps, and go around the Island, as opportunity offers. These too I will have to give up. If I take that position, probably to keep up with my class, I will have to use my eyes in the evening. All lengthy postponement of my return to the States I am opposed to, and equally so to the idea of falling behind my class. I am also convinced that work in Honolulu will not make me stronger as Charley thinks. I have gained five pounds in two weeks up here. It is breathing the air, and going on tramps which will make me strong I think. I need not be idle at home. I will map out my time in reading and studying so as to use it all and use it well. If you wish, for exercise, I will work a certain amount at home every day, an hour or two hours, whatever you please. Because I may not happen to work down-town is no evidence that I am idle.

In conclusion, if you or Father wish me to take this position (if I can get it) for the sake of the salary involved I will cheerfully and willingly do it; but if it is because you think it for my best good that I take it, I enter my protest, prepared in any case to abide by your decision. With love to all.

HENRY.

HONOLULU, No alas, I mean

THE ELLA AT SEA, July 25, ’80.

MY DEAR MOTHER,

It is Sunday afternoon, and we are five days out this noon. We are supposed to be between 500 and 600 miles from Honolulu, nearer the latter than the former I devoutly hope. We have recovered from sickness, and now are going through the inevitable routine of ship’s life, which is not life at all. But why repine? The barkentine Ella did not strike out past Diamond Head for San Francisco, but instead sailed down past Hunter’s point, and so around the Island. Fortunately, we did not get sick immediately, and so enjoyed the views of Oahu, our last of the Islands, to their fullest extent. The Honolulu mountains as they receded in the distance were very beautiful. We sat in the stern of the ship and watched them, till Honolulu faded from sight, and they themselves became only a long range of pale blue mountains pierced with three great openings for the Nuuanu, Kalihi, and Moanalua valleys. We rounded Hunter’s point, and there we enjoyed a magnificent view of Waianai and Waialua mountains looking very high and steep. All this time, I felt perfectly well, which was very fortunate, as the view of the Honolulu mountains was one that I never got before of course, and never will again, unless I go to Australia some day, a thing which I have no present expectation of doing. But late in the afternoon I was taken with a sudden errand to the side, which safely accomplished I retired to my berth and spent a very comfortable night. In fact I have been very fortunate so far as sickness is concerned. The time is passing very slowly, we are counting the days, and oh, how they drag. Still five of them have passed, and the rest will pass, if we only wait long enough. This is poor consolation however. Some of the time is pleasant. In the afternoon loafing is not always a burden. Aug. 6. We will be this noon about 500 miles from San Francisco. Lately the indications for a speedy voyage have been very favorable. But to-day we have a headwind. If the wind should hold as it has been for the last three days, we would reach San Francisco about the 10th or even earlier. But such is life. I do not feel about the voyage as I did when I wrote last. The time for a week past has gone quickly and pleasantly, I have learned the names of all the sails, and also the points of the compass. So I am even with you now, Mother dear. We have made half a dozen rings of rope, with which we amuse ourselves, throwing them over a peg. We keep a careful score of the games, call them matches, and get up a great excitement over them. We have great emulation over making the best record. We eat a great deal. Eat with our fingers entirely. Sitting on the floor around one big dish. Tempus has fugited. I have written half a page on an essay, studied a geography lesson, seen one or two presentable sunsets, played cards until the sight of a pack is enough to send me to the ship’s side, and hired Bowen to black my boots, which job he performed to satisfaction. He has never offered to do it again, however, and so the boots have gone unblacked.

Your worthy son,

NOT ME!

ON THE ROAD SOMEWHERE.

I see the boys have been writing, and so I shall follow their example. With their usual kindness, they have said everything there was to say, and then left me the task of filling out the last two pages. They have behaved miserably on this trip. They have neglected my warnings and scorned my advice. Rex and I hope to reach Oberlin Tuesday, the 24th. In that case, we shall have some three weeks before the beginning of the term in which to prepare ourselves for examination. We both hope in that time, without working to the detriment of our appetites, to accomplish all that is necessary. Rex remains faithful to his traditions. He never sees anything to obliterate the memory of Papaikou. It seemed to be ever present with him, and weighed in the scale with it California, and all the rest of this great country seems very slight and small. We ride a great deal on top of the cars. And, thanks to Mr. Folsom’s timely suggestion, we have not broken our necks by jumping off the train backwards when running thirty or even twenty miles an hour. We have made heavy inroads upon the lunch so kindly provided, but we think it will last. We are expecting to reach Omaha Sunday afternoon at 4 P.M. When we fairly get there, we will feel near the end of our route. We manage to get very good bread, at moderately reasonably rates, along the road, and we occasionally piece out our meals with milk or coffee, though I must say we have little occasion to do so, so bountifully supplied is our basket. The time seems a little long sometimes, but some parts of the journey are very interesting.

With love,

HENRY.

We have just passed Tipton,—1146 miles from San Francisco.

OBERLIN, Sunday, Sept. 5, ’80

DEAR MOTHER,

I am sorry that I could not see more of you just before I came away. But you were so busy, and the time sped on so fast. However I hope that I shall “remember all your counsels,” as George would say. I look back to this year at the Islands with a great deal of pleasure, and the three years, or rather two and a half which must elapse before I see you again seem very short. For of course, Mother, you are coming again to this country, to see me graduate, and visit all your friends again. That is what I have always said, and I say it with a great deal of faith still.

Bowen, Rex, and I have just been out to Berea to see Chauncey’s people. I had my usual nice visit with Chauncey. I know Mother you admire him as much as I do. He is a magnificent man. A practical enthusiast, which is a rare combination. He is an optimist too. Always believes or hopes the best possible of everybody and everything, without shutting his eyes to any facts. His thoughts are strikingly original, and all his ideas are clear and well defined. With all this he is very jolly, and is enough to fill a whole house with sunshine. He has a nice wife too, who reminds me of you, Mother, and two beautiful children. Above all he is engaged in the work which has his whole heart. He is a happy man. Friday morning, we hired a buggy and drove out to Brunswick, to see Aunt Pamelia. We found her on the bed, as usual, I suppose.

We, Rex and I, only stayed about two hours, leaving Bowen there. We drove back to Berea. While in the latter place we had two delightful swims in the quarries. They are very good places to bathe. School begins a week from next Tuesday. I think that Rex and I will get along all right in our studies. I think I shall be examined this week in my Greek and Latin. I shall be all regular before long.

Thursday, September 16.

School began Tuesday. I am studying The Odyssey, Tacitus and German. I have been examined in Horace, Cicero, de Senectute, and The Memorabilia, tell Father, in all of which I have passed successfully. I shall be examined in another term of Greek in a day or two. So I shall soon be regular. Father can be perfectly easy in his mind about me. I shall do one term anyway of the mathematics this term, and perhaps both. I think I shall join a Society soon. I have read Felix Holt the Radical, tell Jim. It is just grand. George Eliot is hard to beat. Felix Holt is a splendid character, sturdy, independent, conscientious, with lofty motives, but a lowly heart. Not a character drawn in the Christian mould, though he is an excellent Christian, but after the model of some of the grand old heathen philosophers, only an improvement on them. The book is full of thought, acute and analytical. I take back Jim, what I said about George Eliot’s being a fatalist, teaching that to be virtuous is not to be happy, &c. I believe that a superficial judgement. I have been making the money fly lately, but I don’t think I have spent more than 18 cents foolishly. After some deliberation, I have come to the conclusion, contrary to Brother Will’s advice, that I will buy books that I want to own, when I come across an edition that suits me, and that I can get at a bargain. Especially poetry. I don’t want to be without my favorite poets, any more than a Christian would want to be without a Bible. Poetry is not a thing to draw from a library, read and return, but something to pick up at odd moments, read a little, think over and digest by degrees. If you try to cram it, it will choke you. On this principle I have bought Shelley, Mrs. Browning and Tennyson. I am taller than C. B. French now and am no longer conspicuous by my lack of size. Where am I going to spend my next summer vacation? School closes here so late that I can’t go and see Carrie graduate, so I want to run down in the winter holidays. Can I do it? I can get three weeks or more then. Just enough for a nice visit. Metcalf my classmate will teach me mathematics till I catch up, so that will be all right. This term is going to be very long—fourteen weeks. Love to all the folks.

Your feckshnit Son,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Tuesday, Nov. 9, ’80.

DEAR FOLKS IN GENERAL,

I have been so busy during the last few weeks that I am afraid that I will not have much more than time for a word a sheet long or so. I suppose that means that I have not had time to write a letter along every day, and consequently, now I am pushed to it, there is nothing to say.

That is doubtless a pitiable state of affairs to get into, but there is no disguising the fact. Not that that is exactly my condition. The difficulty in this case is that there is too much to say, a tremendous jumble of events, nonsense and doings, that it would take a greater genius even than mine to unravel. I might indeed tell you that Garfield is elected. But that would hardly be news to you when you get to this letter. I might tell you that it caused rejoicing in Oberlin, but you know Oberlin politics. I might tell you that Oberlin was so convulsed with joy that it broke loose from all law and order, recitations, study and everything else, and indulged in a grand hullabaloo, and that I guess will surprise you, and that is true. We have had the jolliest times here during the last week that this town ever saw. Our class took the cake, the rag right off the bush. Lest you may not understand these rather enigmatical expressions, I will state that ’83 cleaned out all the other classes, left them way behind. Ours was the only class that could write on their banner, “solid for Garfield.” There is not a single Democrat in our class. I cannot tell you half of what has been done. But election day the College classes marched down with banners etc. to escort their voters to the polling place. Our ladies stayed out of German to fix us up, and we all had the figures “329” stuck in our hats. That is the precise sum which Garfield received from Oakes Ames, and which the Democrats use in their endeavour to implicate him in the “Credit Mobilier.” The Republicans have made a watchword of it. In the evening we met together and marched around town, serenading all the ’83 damsels, and when that arduous task was over with, we cooled ourselves off with some cider all around, up to Mert Thompson’s. Then we blew our horns and made a noise a while and went home. But the big day was the next. We went to Latin as usual at 9 in the morning. But about half past some horns began to be heard, grew louder, fainted away, then grew louder yet, and continued furiously. Every one knew that meant something. We tried to read; could not do it, had to laugh. Then the Prof. tried it. He would get into the middle of a sentence, and then those horns would give a tremendous noise, and he had to laugh. So he gave it up and dismissed us. We ran down town at full speed. A crowd was rapidly gathering. The horns were making a tremendous din in front of the post office. No one needed to be told what had happened. You could read “Garfield is elected” in the air, on anybody’s face, especially in those horns. The Juniors came rushing out of French. Classes were all broken up, and soon there was a large crowd thronging the sidewalk. Students gathered in little knots. Suddenly the enthusiasm found a vent. Processions were formed and paraded up and down the street. Everything was seized upon that could help on the noise and make a funny appearance. Coats were turned inside out. Boards were seized on as clappers. The theologues robbed the stores and paraded the street with new brooms. ’83 as well as others sezed upon a huge wagon, filled it to overflowing and drove around the streets raising flags, blowing, yelling, cheering. Two got on the backs of the horses with their horns. The college bell, the town hall, and the Union school bell, all were merrily rung. After a while we left the wagon and processions were formed again. By and by the ladies fell in, a hundred or more of them. There was no German or Greek that morning for ’83. But I cannot tell you half the wonderful things that happened. In the afternoon a special train was secured, and a party of 700 went down to Garfield’s home at Mentor, a few miles from Cleveland. Neither Bowen nor I went, and we are sorry enough now. But I had no idea that it would be a reception. As it was they all marched down to Garfield’s home in battle array, and when there, Pres. Fairchild made a speech to which General Garfield responded. Every last one of them shook hands with him, and all the College men were introduced to both him and his wife, and some of them even got an introduction to his daughter. Rex went down and so he actually had the hand of our next President in his own. Wasn’t that grand? The other evening they had a final big celebration. It had not the advantage of complete spontaneity like the other one, but we had a tolerably gay time for all that. All the college classes marched except the Seniors, and all the Preps. Every class was fixed up in some striking way. We had huge fools caps and made a striking appearance. The freshmen made the finest, though. They all had a sort of sash across their breasts, and looked just as nice as could be. The procession terminated on the Campus where a huge bonfire was in full blaze. They burned over twenty cords of wood in it, and created some light and a little warmth. Everything around it stood out as though it were day, Tappan Hall, Council Hall, the First Church, etc. Late in the evening they commenced to amuse themselves with a kind of fireworks new to me, which they called fire balls. The Campus was crowded, as the country folk had all flocked in to see the fun, and there must have been two or three thousand people there. Among these, hundreds of fire-balls flew in and out, somtimes lighting at one’s feet, sometimes whizzing past one’s head. I didn’t fancy the sport and whenever I saw one coming I always retired behind the tallest man. The idea is that if you pick them up quickly they won’t burn you. But as some folks have been laid up for six months with them, and they burned folks’ bonnets and things, I concluded that they had some of the properties of fire, and preferred to warm my hands in a legitimate fashion, keeping them tucked away in my pockets. Such is life. I am flourishing like a cedar of Lebanon. I have concluded not to flourish like a green bay tree any more. It is getting played out.

With much love, I am, as usual,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Sunday, December 5, ’80.

DEAR SISTER HELEN,

I received your letter, which came by a sailing vessel some time ago, and will hasten to answer it before I get another from you, which, I hope, will be next Tuesday. Now, as to that plan. It has bust up. I was a little blue when I wrote the letter. But I have got over that now, and I find that reason, judgment, everything tells me to stay right here. What is more, I don’t want to go home; I prefer to stay here. Do, please, destroy that letter; I am thoroughly ashamed of it. I wouldn’t leave my studies now, I wouldn’t have my course broken in upon now for anything. I want to take a course, and I want to do it here and now. I hope that letter wont lower anyone’s opinion of me. It was written in a moment of discouragment, and I suppose every one has those. The fact is I cannot deny that I have galivanted around too much. It has nearly ruined me. What I mean is it has greatly unsettled me. The best thing that could happen to me would be for me not to stir out of this little town till I finish my course. On that account I am glad that I am not to go to Boston this winter. ‘I don’t think going to Europe alone did me any harm, but going to the Islands on top of that. And yet I can’t possibly wish that I hadn’t gone. That is impossible. It is such a host of pleasant memories that I cannot wish it different. Home means so much more to me now, after I have had a chance of comparing it with other countries. I am all out of tune with winter. This last year spoiled me for it. So that now I look forward with much more pleasure to spending my life at the Islands. When my feet and hands get cold, it makes me so mad and disgusted with the climate, that I can’t see an argument in its favor. It is a beautiful day to-day. We have been having the thermometer 8 below zero, but to-day you would be almost willing to swear that it was spring. The thermometer at 56, the sun shining brightly, and a delightful wind. There is one thing we miss at the Islands, and that is the poetry of the change of the seasons. When spring first comes, it seems as though there never were such beautiful days. By the way I never appreciated the indescribable glories of Autumn before. The colour of the leaves is sometimes magnificent, and it is a perfect luxury to cross the Campus. By the way Helen, did you know that Oberlin is a beautiful place. When I first got here this year in August, it was lovely. In summer the college square is a genuine park, and it is crowded with magnificent trees. They wont equal Algerobas and Monkey-pods and tamarinds though. Tell Ida M. that please, from me. Tell her oaks and elms and maples and beeches are nice, but they are not equal to the Island trees. Besides there is not the variety in them. Just think of the difference between all of the three trees mentioned and mangoes. They are not one of them alike even to the most casual observer. While I have not learned to distinguish all these trees yet, I am just learning to see what nature can do with just light and air and sunshine and clouds and sky, while the trees are all bare and the grass a withered green, and the mud thick in the streets and the architecture horrible and the country as flat as a pancake. And the result is glorious. However, it is not so fine when the sunshine disappears and the sky is leaden and gray, and the atmosphere thick and murky with fog and mist and rain. As for Geo. Macdonald, Helen, I don’t once deny that he is fine. If I were counting up the novels in this world which I thought worth reading, and counted them all on the fingers or one hand, one of his would be among the number. But then, fine as he is, it would be unreasonable to expect him to equal George Eliot, who is the high water mark among novelists. You say he is of heaven and she of earth. The distinction is a good one. I don’t know much about painting, but I have an idea that it would be about the difference between the lovely spiritual saints and Madonnas of Fra Angelico (I think that’s the man) and the Hebrew Prophets painted in the Sistine Chapel by Michael Angelo. The Hebrew Prophets were men of the earth. Be sure of that. The same tendency that would make me exalt Macdonald above George Eliot prompts my heart to place a simple ballad like “The day is done” above the finest classical music, or exalt some beautiful tale of Hans Christian Andersen’s whom I admire and revere, above “Les Misérables,” or George Eliot herself. Geo. Macdonald has a vast number of styles. Think, for instance, of “St. George and St. Michael,” and then of “The Portent,” of “Phantastes,” and then of the “Seaboard Parish.” I have read a great deal of Geo. Macdonald—as much of him as of any other novelist. But I will read the books you speak of, except “Ranald Bannerman’s Boyhood.” I have not actually read that, but I have looked through it pretty carefully, and have contracted, perhaps hastily, a very poor opinion of it. Geo. Macdonald is very fond of writing books without any of the point commonly attached to stories, and, to a certain extent, I follow him. But there is such a thing as overdoing the thing, and writing a book without any point at all. That, according to my idea, is the difficulty with Ranald Bannerman. The events of few boyhoods are significant enough for a novel, in my opinion. A story should present a life in its unity. It should, at least, paint the turning points, the crises that make or mar the character. For the same reason that John Halifax gains in force because it is a history of a life, Ranald Bannerman fails because it represents but a short and not very important period of life. It is, at best, a fragment. The chief interest of the book hinges, perhaps, on Turkey. But he is a man; there is no boyhood about it. Or, perhaps, the chief interest hinges upon some of Geo. Macdonald’s theories of parental training. If so, Ranald Bannerman is a nonentity—nothing but a foil for his father. In that case, the book may. be very instructive to parents, and indeed to everybody, and may be very valuable. But it is a poor attempt at a novel. You may think, however, that I am very cheeky in “talking so much about a book that I have not read and I guess I am. So I will take it back. (Dec. 10). Charles Kingsley is nice. I read his “Westward Ho,” coming over on the Ella. It is full of the author, and displays his hobbies to the utmost advantage, which is manly Christianity. A very common hobby with Englishmen. Being a kind of reaction, which does not exist in America, for here, we never thought it particularly brave and manly to fight, and never made a God of muscle, so that we never need to write books to prove that a man may refuse to fight and yet not be a coward, like Thomas Hughes. However the book presents a fine picture of the Elizabethan, which the author thinks a heroic age. The characters are better than the book. Some of them are really very noble, and the book is written with so much enthusiasm, and such an ardent admiration and sympathy with nature. In fact enthusiasm is the principal element of the work, and it is so sincere that you cannot help being stirred yourself. So I have a weakness for Westward Ho. My memory of it is full of bright pictures, pictures of a beautiful coast with lofty cliffs, and shelving beaches, bronzed sailors, and fierce sea fights, and fine pictures of the tropics. In parts it is great. And the best adjective to apply to the whole is noble. If you like Kingsley I should advise you to read it, if you have not already done so. The steamer came day before yesterday, bringing a letter from you, for which I was much obliged. Reky had I believe eight letters. But he ought to get more than I, for he writes more. However I think I write quite as much as desirable. Ida M. Jim Julia, and Ida B. and Will, owe me letters. However I did not write to them so as to get a letter out of them, for I know they are all busy or sick or something. Have you read Wilfred Cumbermede? I think you told me you had not for a long time. Before you pass final judgment on Geo. Macdonald you must read that. It is altogether the finest that I have read, in my estimation. However, some of his I cannot compare because I read them when so young. It has been my great misfortune to read a vast number of fine novels when too young to appreciate them. However, I suppose that is better than to read a lot of trash. Wilfred Cumbermede is one of those books that I spoke of, where Geo. Macdonald does not follow the beaten track, and here I admire him wholly. The friendship between Wilfred and Charley is fine. A strong friendship is a beautiful thing, and I wonder that poets and novelists don’t give us more of it. How provoking it is that I should have come away just as all the improvements are being introduced. How I should like to see Will’s new house. Fred’s room and the library must be like the octagon room that you girls had at the Falls of the Giessbach. What a glorious place that was!

Love to everybody,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Thursday, December 9, ’80

DEAREST MOTHER,

The Island mail came yesterday, bringing a good long letter from you, and one from Helen. Many thanks. It must be rather lonesome in the big house now, with nobody there but you and Father and Helen. By the way will you convey my aloha to Ah Yung and Laurence. I suppose they are both there yet. But to business. You ask me as to books. A good many of them, the most of them, I left on purpose. But there are a few which I meant to bring which I did not. For instance some of the Guide books. Especially Baedeker’s, Paris, and Switzerland, and Italy, if that is there. I feel completely lost without the Switzerland. I never can finish my Journal without that and the “Paris.” To be sure, I don’t suppose that I would finish it anyway. But I might if I had the books. For sometimes I long to very much. I don’t think I ever borrowed any book of C. . . A. . . I remember one night I was up to his house, and he persisted in offering me the loan of about every book that he owned, but I am quite certain that I refused them all. What I could have possibly wanted of any May Martyn, or any other Martyn girl, I can’t imagine. Rex has not met any friends of his grandmother that I know of. Mrs. Ellis is very anxious to see him but we have not called there yet, though we went once when they were away from home. I hope that we will go before long though. Mrs. Jewett has got a Bro. here 14 years old, about. He left the Islands ten years ago. Tell me all about him please. I have a vague remembrance of some Gulick boys whom I used to go and see, and whom you always used to hold up to me as models of virtue which I was to imitate. But I can’t remember whether they could lick me or I them. However this chap has two brothers. I believe one about 19 years old, who is at College in the East. Miss R. . . sends her love and thanks you for all the kindnesses you have done her. I know the way Uncle gave me the message it was a good deal nicer than that but I have forgotten just what it was. I know it quite touched me and made me feel that gratitude was a pretty nice thing. I know that lots of your friends have sent messages to you, but I have forgotten them and the messages both. It all goes in at one ear and comes out at the other. But I know that lots of messages have been given me. I shall put it down as Oberlin sends you its love. It will be a long while before you are forgotten here. Besides you will be back in two years from next spring, anyway. It doesn’t seem long, does it? And it won’t be.. I notice in your letter that you hope Carrie and I can get together somewhere and spend the vacation together. I suppose you mean summer vacation. I have given up Boston this winter of course. For in your letter before this last you said, “I suppose your Father has written you not to go to Boston this winter”. He didn’t write as it happens, but I took it that that settled the matter. So I stay in Oberlin this vacation. But I shall have enough to keep me busy. Geo. Mead and I propose to read a little Greek out together for amusement. Last night was the Oratorical contest. It was pretty good. This is a very pleasant term’s work both in Latin and Greek. In the latter we have been reading Homer, and are now at the Lyric Poets, both of which are fine, and in Latin we have read about 90 pages of Tacitus. He is the finest prose writer that we have read. I enjoy it immensely. My health is first class. I am not troubled with the blues. With love to all,

I am your affectionate Son,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Wednesday, December 29, ’80.

DEAR FATHER,

I received your good letter sent by the Ho Chung last week. It was very welcome. It found me sick with a cold, and cheered me right up. I had just been wishing that I might have some mail from home, but was without the least hope of it. So it was a very pleasant surprise. The cold that I spoke of, was really quite a bad one for me. But by care and a little of Auntie’s doctoring, I have been enabled to throw it off very rapidly. I shall take excellent care of myself, so that you need not have the least fear for me. I shall not neglect to wear my overcoat, whenever it is the least cold. I am too little fond of cold weather to care to expose myself. It has been quite warm for the greater part of this month, but it has now set in cold again, and this morning the thermometer stood at 10 degrees below zero. We have made some slight change in our arrangement here. I now board with Auntie; Rex however still continues to patronize Mrs H. . . I very much prefer to be with Auntie, as it is much more homelike and I feel more free to do as I please. If I don’t happen to feel like talking, nobody comments upon it. But at Mrs H’s., if I don’t immediately upon coming to table commence to smile and laugh and make foolish remarks why they think that I am sick or have lost all my friends. Neither of which is the case, but I am merely weary of the froth and bubbles of table talk, notwithstanding that I make three fourths of it generally myself. It does seem a pity that you should travel so in your old age. But I suppose it can’t be helped. However I shall regard it as a sign that you are better than you were when I last saw you. As to my working next summer, I shall be glad to. I had thought of it before a word was written from home about it.

Your affectionate Son,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Thursday, Feb. 3, ’81.

DEAR SISTER HELEN,

As usual, it is almost time to send letters home again, and I have only written about a sheet. I cannot, like you, make up for all deficiencies in a day, nor have I Reky’s facile pen, which eclipses even the longest efforts of brother Will. So I shall send very little home this time. I was going to write such a lot, too. Such is the fate of good resolutions, mine especially. We are having fearfully cold weather just now, the thermometer goes down to ten degrees below zero mornings, and freezes the very blood in a man’s bones. There isn’t any blood in a man’s bones, is there? Well, anyway, it chills one to the bone, and freezes, or curdles, as you please, the blood in his veins, and instead of putting snap into a fellow it takes it all out. It uses me up to walk down town on a cold morning. Bronson Alcott gave a lecture here last term on the Concord celebrities. He spoke of Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller and his own daughter Louise. It was very interesting. He introduced us to the private life of all of them; especially Emerson was interesting. He told just how he wrote, kept a journal and whenever he had a good thought put it down. And his essays are the result, being merely a piecing together of the fragments of his journal. I never knew before how shy Hawthorne was. He had a kind of turret hitched onto his house, where he could retire when he was disturbed. All he said about Thoreau was also very interesting. I have bought Macaulay’s essays, and have taken a good dose of them. I admire him more and more every day. His style is certainly unrivalled. Some passages are magnificent. I do not think much of him, though, in other respects. Since I bought these volumes I have read “Criticisms on the Principal Italian Writers,” “The Athenian Orators,” Mitford’s “History of Greece,” and “Milton.” I am inspired with a desire to read Dante now. Shelley is one or my standard poets. I have a cheap edition of him, and have just read “Prometheus Unbound,” which is much praised. Some parts or it I like very much, but most of it I could not appreciate at the first reading. His short poems are the most exquisite ever written. Keats too I have been reading some, but I have not tackled the “Endymion” yet. I am reading though, (would you believe it) “In Memoriam.” Some of it I like. I feel my ignorance more and more every day. There are two things which I am ashamed to acknowledge; one is that I am 18, and the other is that I have been to Europe. I don’t like to confess that I have gazed upon the most glorious masterpeices of painting and sculpture with as little appreciation as the Vandals.

With much love,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, February 26, ’81.

MY DEAREST MOTHER,

Your short letter to me, enclosing one to Bowen, I received yesterday. I was glad to get it, but sorry for the conditions on which it came. That is, you said that it was feared that the other steamer would not stop at all, when it was learned that the small pox had got around to Honolulu. O dear, I am afraid Reky and I will both die if we don’t get letters from home next Tuesday. How horrible that the small pox has come. I am commencing to share all the most vindictive sentiments against the Chinamen. I am rather ashamed of it, but then I can’t help it. And I am rather afraid that the lofty disinterested philanthropy of most Eastern people would vanish as my benevolent feelings did on nearer approach to the wretches. I wish they could all be put into a big bag and taken out to sea, and shoved overboard, or that the whole race had only one neck, as some king or other said of some people or other, that it might be chopped off at one fell swoop. Do not be frightened Mother. All this bloodthirsty talk is merely a bit of diplomacy to draw a long letter from you reproving me for my depravity. I’ve let the cat out of the bag, haven’t I? Never mind, send the long letter just the same, please, dear Mother. Don’t think, Mother, that I froze last winter. I didn’t at all. The grey suit did very well. And I knew that if I got a new suit last winter, it would be wasting a good lot of money, for I thought I would outgrow the other before I could wear it again. I was warm enough. But I shouldn’t object to having you fly right over here and dress me up warm. There would be some prospect of it, for you would probably bring some money with you. The cold that you speak of I recovered from long ago, of course. Don’t suppose from anything that I have said that I am dissatisfied about money or regard myself as stinted. I don’t. I am perfectly satisfied. $ 300.00 a year ought to be enough. But the simple fact is that on that sum I am not a millionaire. And when you write about dressing warmly and well, etc, why I don’t carry money enough around in my pocket to buy a suit of clothes. I must save carefully for four or five months before I can get a new suit. You see expenses pile up and I have to figure a long way ahead. The winter is breaking up. The snow is about all gone. It is quite warm, but a disagreeable day. With lots of love,

I am your loving Son,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Sunday, February 26 ’81.

DEAR SISTER HATTIE,

Carrie has come and gone. It was just like an angel from heaven sent down to illuminate our barren Oberlin existence. The time when she was here just flew like the wind. And now she is gone. Reky and I both felt bad enough to cry when we walked back alone from the Depot. We didn’t know till then what a happy time it had been while she was here. It is just like beginning all over again now. And my courage is all gone. You see the whole thing was so sudden. We didn’t know she was coming home till summer, until she wrote a postal telling us that she was going home in March. And then I was so busy I didn’t realize that she was coming. How could I? And then she came. All of a sudden too, and only to stay a few days. And then I was happy without knowing it almost. I went at my books with a zest. I went to class with a zest. But I was busy and Carrie was busy. She had shopping to do and friends to see. And I had hard lessons to get. And so Friday came and she was to go that night. We took tea at the Brand’s. After supper we walked home, and were jolly, laughing and joking. And then when we got down to the Depot we waited a while, for the train was late. And when it came, it came so suddenly, we weren’t watching for it. And we hurried aboard, and the train started before Carrie had even got a seat. And we had to jump off, and she was gone. And then, for the first time, I took in the whole business. And it seemed as if I hadn’t had a chance to speak to her: hadn’t had a word with her. That’s the way it is in this world. Man’s eyes are blinded. He trifles with his opportunity. And when it is gone he awakes. Life is all one great opportunity. And we don’t know it. And the time flies by, the days and months and years, and when the best of it is past our eyes are opened, and we see all that we have lost, and know that it is gone — passed for ever. (Hang it!) Well such is life. (Only don’t think I am sentimental and silly.) I shouldn’t have written such stuff as I have in this letter. It sounds rather blue. And I ought to be happy most of the time. I shall soon settle down into the old ruts again and be as “happy as a big sunflower, that nods and bends in the breezes”.

Your loving Brother,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Friday, March 4, ’81.

DEAR ANYBODY AND EVERYBODY,

The mail from home was welcome as usual and not late. From Mother’s letter to me we were afraid that no mail would come, and so when the letters actually came, Reky and I were overwhelmed with joy. Helen’s letter and Father’s long one, with a short note from Mother was my mail. You can imagine how astonished I was to hear of the plan to come here, and overjoyed too, of course. Only I curbed my exultation, so as not to be too much disappointed if you don’t any of you come after all. However I think it will be a terrible misfortune if you don’t come now, for the proposition has certainly created sensation enough on this side of the water, for you to come. The letters were exasperatingly indefinite. Father’s letter stated the plan as a possibility, hardly more than that. Helen’s letter had no date, but I think was written later than the other. She spoke on the last page as if the whole thing was settled, said she wished they were going on the March instead of April steamer. So I took it for granted that her letter was later than Father’s, that the whole thing was decided that you were all coming on the April steamer, and acted accordingly. Carrie had gone as far on her way home as Milwaukee. As soon as I received the letters I telegraphed to her there. I wrote of course, immediately. She is still there, and probably will not go home on this steamer, but will come back to Oberlin, and study, and wait for you people to come. She expresses great delight at the idea, and though no doubt would like to go home on some accounts, yet evidently vastly prefers to be here with Father, where she can prosecute her studies, which she says she hates to leave. She has made her arrangements to go home, but that is a mere nothing. Arrangements are not hard to make and unmake, as our. family surely ought to know, if anybody does. Carrie was going to visit in Kansas, but will give that up for the present. She jumps at the chance of coming here to study, she says. I do hope you will surely come, for it will be worse than ever to have Carrie come here a little while and then go home after all. I didn’t know how much I missed the home folks till Carrie came and went. It is life, heaven with you. Mere existence alone. But of course, I only want you to do just what is best. I don’t see how Father is to be invigorated by coming here just at the beginning of summer? Won’t the heat be hard on him? Of course May, the first month he spends here, will be invigorating, but how will it be after that? June, July, August, how will he stand those? But the very thought of having Father, Mother, Carrie and Helen here together, and of keeping house somewhere in the centre of the town, in some nice house, fairly makes my mouth water. It makes my heart leap to think of it. It is too good to believe.

Lovingly,

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Thursday, April 26, ’85

DEAR PEOPLE AT HOME,

I have had the misfortune to be put on for Junior Ex. for an English Oration. I just want to know, dear folks, what I am to do for sure, next vacation. I regard the plans for work as visionary. I think there is a fair chance that I may be able to get some honest, hard, unremunerative work next vacation, to which I can turn my attention. But as for finding some nice place in a carpenter’s or other mechanic’s shop, where I can learn a great deal, that is not a probable thing, I think. I must be willing, of course, to turn my hand to anything that comes up. Now the question is, if I can’t get anything better than feeding pigs for my board, am I to do that, in preference to going to Winchendon, Milwaukee, New York or Kansas? Whatever the decision, I shall cheerfully abide by it. Will and Ida, I have just rec’d my certificate of stock from the Book Ex. I shall be glad to get you books at a discount, at any time, or any others of the Family. You will find a list of their publications in the “Good Literature,” which I send Helen by Carrie. The stockholders discount is (1-3) one-third off. Must close. Much love; in haste..

HENRY.

OBERLIN, Sunday, May IS, ’81.

DEAR SISTER HELEN,

I had the unexpected pleasure of receiving a good long letter from you the other day with one from Hattie, by same sailing vessel I suppose. Dear Helen, you needn’t think you have deserted me, and suffer qualms of conscience. I’m sure you are altogether the most faithful correspondent that ever existed. You have written to me every mail but one since I have been here. And you have written by so many sailing vessels that I have almost got to expecting an intermediate mail as a regular thing. I was overjoyed to get the photographs you sent me. But don’t think. I don’t admire the Royal Palms. I was completely converted on that subject before leaving the Islands. The effect of that Royal Palm up at the Mausoleum is something magnificent. And that in the Kawaiahao Cemetery, ditto. Reky and I are regular showman with our Island pictures, and Bowen is too. He has taken them with him out into the country and exhibited them to a great circle of friends and relatives. We have converted a great many to the belief that the Islands are a very nice place, and aroused in everybody an ambition to go there. You speak of not having written or so long that you feel like a stranger. I don’t think it is because one hasn’t written for a long time, but because you have lived a great deal since writing last. So that for a time I am really forgotten, and you wake up to my existence suddenly with the force of a discovery, and then I seem something very far away, like a part o. your past. I know that is the way it is with me. I wish I could be there to play backgammon with you, but when I got there Helen, I don’t believe you would want to very long. You would play about one game, and then hide the board, so I wouldn’t be reminded of it.

May 27.

You must not say “scraggly Oberlin” Helen, for you must remember that we have just been having spring here.

“When the earth with blossoms again is gay,

And the fountains gush in the lovely May.”