Читать книгу Squeezing the Orange - Henry Blofeld, Henry Blofeld - Страница 11

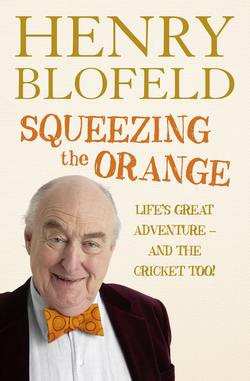

THREE The French Women’s Institute

ОглавлениеCricket had me in its grip before I had been at Sunningdale for a year. The following June, in 1948, I found myself at Lord’s with Tom and Grizel sitting on the grass in front of Q Stand eating strawberries they had brought up from Hoveton and watching the third day of the second Test against Australia. I became one of what is now a sadly diminishing band of people to have seen the great Don Bradman bat. He made 89 in Australia’s second innings before being caught at shoulder-height by Bill Edrich at first slip off Alec Bedser. I can still see the catch in my mind’s eye. As he departed, dwarfed by that wonderful and irresistible baggy green Australian cap, I was sad that he hadn’t got a hundred, but everyone else seemed rather pleased. I distinctly remember him facing Yorkshire’s Alec Coxon, a fast bowler playing in his only Test match. A number of times Coxon pitched the ball a little short, and Bradman would swivel and pull him to the straightish midwicket boundary, where we were sitting on the grass. Once I was able to touch the ball – what a moment that was.

It was not only at school that I revelled in cricket. In the Easter holidays I went to indoor coaching classes in Norwich taken by the two professionals who played for Norfolk : C.S.R. Boswell, a leg-spinner and late-middle-order batsman known to one and all as ‘Bozzie’, and Fred Pierpoint, a fastish bowler. Then, in the summer holidays, Grizel would heroically drive me to all parts of Norfolk, however inaccessible, for boys’ cricket matches in which I became a fierce competitor. We would set off in the morning in Grizel’s beetle Renault, with a picnic basket on the back seat. Grizel was nothing if not a determined driver. Whenever she changed gear it was as if she was teaching the gearstick a lesson, and she generally treated the car as if it was a recalcitrant schoolboy. Some of the lay-bys in which we stopped for lunch became familiar haunts over the years. A hard-boiled egg, ham sandwiches and an apple were the usual menu, and it never helped things along if I dropped small bits of eggshell on the floor.

The cricket usually began at about two o’clock, and I remember many of the mums being, if anything, rather more competitive than the players. There were certain key players in the teams I played for: Jeremy Greenwood bowled very fast, Michael Broke’s off-breaks took a long time to reach the batsman, Jeremy Thompson – whose father Wilfred had bowled terrifyingly fast for Norfolk and had captained the county – was another star, while Timmy Denny did his best. Henry and Dominic Harrod, sons of the famous economist Roy Harrod, had their moments, and the many Scotts all played their part, especially Edward, who bowled fast – we later played cricket together at Eton. He was a cousin of the Norfolk Scotts, although he lived in Gloucestershire, and was to become one of my greatest friends. The two Clifton Browns also contributed, and their mother scored like a demon in a felt hat.

The Norfolk Scotts lived at North Runcton, near King’s Lynn. Father Archie, as tall and thin as a lamp post, was the first Old Etonian bookmaker, and his delightful and cuddly wife Ruth was a huge favourite with all of us, forever laughing and always a fount of fun. She was also great friends with the Australian cricketers of Don Bradman’s generation and before. A particular ally was the famous leg-spinner Arthur Mailey, a great character and the most delightful of men. He had been a wonderful bowler, as well as being a brilliant cartoonist. For some reason he took a great interest in my future as a cricketer, and one of my proudest possessions is a booklet he wrote in 1956 called Cricket Humour, with some amusing stories illustrated with his own drawings. The front cover is a lovely cartoon of Mailey himself trying to bribe the umpire with a fiver. On the first page he wrote: ‘My best wishes for a successful cricket life. Saw you play at Runcton about 3 years ago and am very pleased about your progress. Arthur Mailey ’56.’ Later in life I put together a small collection of his original cartoons, and they are a great joy.

In between those holiday matches I would go to Lakenham cricket ground, with its handsome thatched pavilion, where Norfolk played their home games. Now I would be ticked off for spilling my picnic eggshells on the grass in one of the little wigwam-like tents which lined one side of the ground. One of them had a sign hanging on the outside which proclaimed that it belonged to T.R.C. Blofeld. Inside was a small table and some rickety deckchairs. Those days at Lakenham gave me an early glimpse of what I think I supposed heaven was all about. Norfolk never won very much, but my goodness me, it was exciting.

I always brought along my own puny bat and a ball, and sometimes I was able to persuade someone to bowl at me on the grass behind the parked cars at the back of the tents. Among them was the vermillion-faced Mr Tarr, who was the Governor of Norwich Prison and, I hope, a better governor than he was a bowler. Every so often, as I was sitting in a deckchair watching the cricket, a four would be hit in my direction and I would stop it and throw it back to the fielder. Not quite the same as fielding to Bradman, I know, but you took what came. Just occasionally there was the thrill of a six being hit towards our tent, forcing everyone to take cover in a mildly cowardly panic. My early heroes from these occasions were an eclectic bunch, including the afore-mentioned Wilfred Thompson; David Carter, military-medium; and Cedric Thistleton-Smith, who was always out unluckily – all three of whom came from west Norfolk and were thriving farmers. Lawrie Barrett, short and dark-haired, a tiger in the covers, thrilled us all a couple of times a year as a middle-order batsman and succeeded Thompson as captain. H.E. Theobald was a large man who, like his Christian name (it turned out to be Harold), remained a bit of a mystery. He was not in the first flush of youth, and nor was his batting. Then there was good old, eternally cheerful, round-faced Bozzie; we loved his spritely cunning with the ball and his enthusiastic twirl of the bat when his turn came late in the innings. He had a kind word and a smile for everyone.

Village cricket also played a big part in my life. The heroes for Hoveton and Wroxham did battle on the ground set up by those German prisoners-of-war. I had some fierce battles with Nanny, who refused to let me go and watch them when they were at work. I was determined to wear the German policeman’s helmet I had been given by some returning warrior. She felt it would not have created the right impression, and unusually for her, had a word about it with Grizel – who of course agreed wholeheartedly. So my one intended thrust for the Allies was nipped in the bud.

Hoveton was captained by the ever-thoughtful opening batsman Neville Yallop, whose black hair was swept back with the help of Brylcreem. There was Fred Roy, of the huge eponymous village store, who opened the batting with Neville and bowled slow, non-turning off-breaks; Arthur Tink, whose military-medium was full of unsuspected guile – as I dare say was his gypsy-like wife, Mona, who looked incredibly beautiful and never said anything. The vibrantly moustached, ample-figured Colonel Ingram-Johnson kept wicket and batted in an Incogniti cap. He had Indian Army and Rawalpindi coming out of every aperture. Colin Parker, a local boy who bowled at a nippy medium pace, had an attractive, befreckled red-haired sister and a father who umpired in partnership, I am sure, with the ubiquitous gamekeeping Carter. Bob Cork, a small man who I think was a blacksmith, ran around with terrific enthusiasm, but not a great deal of effect. When I was about thirteen and had been allowed to join in a fielding practice, I tried to take a high catch and the ball dislocated my right thumb. Bob was quickly to the rescue, and agonisingly yanked the wretched joint back into place.

I lived for cricket, in boys’ matches, on our ground at home, and at Lakenham, and spent many of my waking hours in the summer holidays at one or other of the three. Added to which, and to Nanny’s mild disapproval, I took my bat to bed with me. That, of course, was in the days when bats smelled redolently of linseed oil. I am not sure I have ever found a better smell to go to sleep with.

In the winter holidays the gamekeepers and shooting took over from cricket, and I have to confess I also took my gun to bed with me. I spent as much time as I could with Carter, Watker or Godfrey learning about trapping vermin, feeding pheasants and partridges, and looking for their nests in the Easter holidays. If a nest was in an especially vulnerable position we would pick up the eggs, which would then be hatched by a broody hen, and the chicks brought up in pens until they were ready to be put back into the wild. Carrion crows, sparrowhawks, jays, magpies, stoats, rabbits and rats all had to be eliminated where possible, and kept in proportion if not. I learned many of the tricks of the trade. What fun it was, and I was unable to put down a book my father gave me called Peter Penniless, which was about the adventures of a country boy who scraped a living by poaching and selling the fruits of his labours. Poaching was something that went on a good deal, and as I was later to learn, was perpetrated not only by the unscrupulous from neighbouring villages and Norwich, but by some, like Lennie Hubbard, as we have seen, who worked, above all suspicion, on the farm. Sometimes the ungodly would be caught and brought to justice, but more often than not they got away with it. It was all part of the excitement of growing up among the Norfolk Broads. There were poachers on the Broads too, who tried to shoot duck and to catch fish and eels. Johnson was the head marshman, and another heroic figure. One of his sons was in the RAF in the war, and once came back on leave bringing with him the first banana I had ever seen, let alone tasted. It was black and well on the way to being rotten, and tasted filthy – not that I was about to admit it.

It was from this background that I once again jumped into the back of my father’s car, which had moved up a peg or two from the Armstrong Siddeley that had first taken me to Sunningdale. It was in the old 1932 Rolls that we made the journey from Hoveton to Eton on 23 September 1952 – which was not exactly the way I wanted to spend my thirteenth birthday. It was another anxious trip. I had long looked forward to going to Eton, but now that the day had arrived, I was more than a touch nervous. Twelve hundred boys, tailcoats, strange white bow ties which had to be tied with the help of a paperclip, my own room, a house of forty boys, a completely new set of rules and regulations to learn. I would have a much greater degree of freedom than I had experienced at Sunningdale, where obviously the young boys had to be kept under close and watchful guidance. Eton was a huge step nearer to the big wide world, and was both frightening and exciting because of it. ‘There will be plenty of other new boys,’ Grizel had said to me in a voice which suggested that that put the argument to bed once and for all.

After a journey of about four hours, not particularly helped by Grizel trying to jolly me along in between spirited bouts of backseat driving, we all trooped in through the front door of Common Lane House and shook hands with M’Tutor and Mrs M’Tutor, as they were known in the Eton vernacular, Geoffrey and Janet Nickson. Geoffrey Nickson was bald and quite small, with a beaming smile, a warm handshake, twinkling eyes and a chuckling laugh, all of which made that first frightening step so much easier than it had been at Sunningdale. He could have taught Mr Fox a thing or two, but then I was five years older, and better able to cope.

As I sat on the ottoman in my own room at Eton, with its lift-up bed hidden behind curtains, my own friendly shooting prints on the wall – I still have them today in my bedroom – and a few family photographs, I was acutely conscious that I was now on my own, in a much more grown-up society. It was a help to know that my brother John had been through it before me, in the same house, and had survived. All the new boys were in the same boat, but at that moment it was a personal, not a communal thing. When we arrived we were all tremulous little islands in a rough sea. I had had many lessons at home on how to put on a stiff collar, how to use collar studs and how to tie that alarming white bow tie – alarming until you had done it once, after which it was simple, as many apparently difficult things turn out to be. There was an official form of ‘cheating’, in that the white strip of the tie had a hole in the middle, through which you put the collar stud between the two ends of the stiff collar. One end of the tie was then held sideways across the collar, while the other was tucked over the top by your Adam’s apple, and then thrust down inside the shirt, where it was held in position by the paperclip. This was the ‘cheating’ bit. The two ends were then pushed under each side of the collar – simple really – then it was nervously down to breakfast, my first outing in my tailcoat. I had well and truly begun my first half at Eton.

We new boys sat at a small table in the corner at one end of the boys’ dining room, which had the somewhat mixed benefit of being presided over by ‘My Dame’ (M’Dame), who was a sort of high-falutin’ house matron. She was called Miss Pearson, and while I must say I never found her particularly loveable, it was a less aggressive sort of unloveableness than Miss Paterson’s. I suppose M’Dame had to be bossy, but she made rather a business of it. When I came down, extremely frightened, to that first breakfast I found myself being stared at by those who were not new boys in a ‘Look what the cat’s brought in’ sort of way.

I was lucky with my housemaster, M’Tutor. Geoffrey Nickson had all the qualities of a perfect schoolmaster. He was kind; he was thoughtful; he was never in a hurry; he never panicked; he never shouted; he was unfailingly interested in everything you did; he suggested, firmly at times, rather than ordered; he had a splendid sense of humour; and he punished firmly and without relish or enjoyment. At Eton, like all masters, he was known by his initials, ‘GWN’. The ‘W’ stood for Wigley, which was harmless enough, but gave rise to a certain amount of childish amusement. GWN was a classical scholar. He was not an Etonian himself, but you would never have guessed it. I arrived at Eton near the end of his fifteen-year spell as a housemaster, which finished at the end of the summer half in 1955. I don’t think it would have been possible not to love GWN. He was always immensely approachable – a schoolmaster, and yet very much not a schoolmaster. He had a wonderfully ready, infectious and enthusiastic smile. He was always fun, whether you were a member of the library, the elite five at the top of the house, who sat at his end of the long dining-room table, or a lower boy, as we all were for at least three halves, whom he took for pupil room, known colloquially as ‘P-hole’, at the end of formal lessons each morning in the mildly improvised classroom outside his study. He was equally enthusiastic whether bowling his leg-tweakers in the nets or watching members of his house in whatever sporting contest they were competing in against other houses. A perfect illustration of GWN’s skill as a schoolmaster came when he caught four of my friends playing bridge – cards were strictly illegal. He made them all write a Georgic which entailed copying out more than five hundred lines of Latin verse. He then asked them down to his study every Sunday afternoon to teach them to become better bridge players.

On Sundays, Mrs M’Tutor, Janet Nickson, who was the perfect complement to GWN, would read to the lower boys in her husband’s study, and we had to suffer such improving literature as Lorna Doone in her slightly schoolmistressy voice. When we became upper boys, GWN himself read to us in pupil room. We listened spellbound to, among others, Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and J.K. Stanford’s The Twelfth, about Colonel the Honourable George Hysteron-Proteron’s exploits on a grouse moor on 12 August, the opening day of the season. GWN himself was no mean shot, and a considerable fisherman.

One of the first exams a new boy had to go through at Eton was a ‘Colour Test’. There were goodness knows how many different caps, or colours, as they were known, given exclusively for prowess in sporting pursuits ranging from cricket to rowing to the field game, the wall game, fives, racquets, squash, beagling, athletics, gymnastics, tennis, soccer, rugby and many others besides. About three weeks into my first half new boys gathered in the library – in non-Eton talk, the house prefects’ room – where they were asked many searching questions. A profusion of different-coloured caps were produced, and we had to identify them. We had to show that we knew the masters by their initials, that we understood the geography of the place and other Etonian lore, not least the idiosyncratic language which was peculiar to the school. The geography was extremely important, as once the Colour Test had been passed, we lower boys began our fagging career. If you were told by a member of the library to take a fag note (a written message) to a boy in, say, DJGC or FJRC, it was as well to know where you had to go. When a member of the library needed a fag, he would make a ‘boy call’, his yell of ‘B-o-o-o-o-oy’ going on for twenty seconds or so. The last lower boy to arrive got the job. Having taken middle fourth in my Common Entrance, it was my lot to be a fag for five halves.

I enjoyed my five years at Eton as much as any period of my life. As I had discovered at Sunningdale, having the luck to be reasonably successful at games was a great help. Good schoolboy games players become little tin gods, a status which provides a certain insulation against the petty struggles of school life. Of course, this doesn’t happen at once. I spent my first half trying to unravel the mysteries of the field game, an Eton-devised mixture of rugger and soccer played with a round ball. There is a sort of mini scrum, known as the ‘bully’, and much long and skilful kicking up and down the field by the three backs, one behind the other called ‘short’, ‘long’ and ‘goals’. I played at ‘outside corner’, on the edge of the bully, a sort of wing forward. I was never any good at the game, and didn’t enjoy it much. The umpire only blew for infringements if the players appealed. ‘Cornering’, which meant passing, and ‘sneaking’, being offside, were the two most common offences, although the most enjoyable, for obvious reasons, was ‘furking in the bully’, which was lightly, delicately and tellingly adapted on almost every occasion. This was for what was known in less esoteric circumstances as back-heeling, as would happen in a rugger scrum. The wall game was another complicated and esoteric Eton institution. Like many Oppidans (non-Collegers), I never played it, and I still have no clue about the rules. It is best known for the annual mudbath that takes place between the Tugs (Collegers) and the Oppidans on St Andrew’s Day alongside a high and extremely old brick wall in College Field, by the road to Slough.

I had a terrific time in my first half, being ‘up to’ Mr Tait for classics. He was known as ‘Gad’ Tait, for the obvious reason that his initials were GAD. Most of the beaks’ (masters’) nicknames were pretty unoriginal. Dear old Gad Tait was a very tall man who when he rode a bicycle wobbled so perilously and entertainingly that it was like a balancing act in a circus. He had a genius for making the learning of Latin seem interesting, entertaining and good fun, when it was palpably none of those things. By then, of course, we were well past the ‘Caesar conquered Gaul’ stage, which had seen Miss Paterson rise to fevered levels of ferocity in the second form at Sunningdale. At Eton we were very much free-range pupils, by comparison to what we had been at our preparatory schools. Now a good deal of our work had to be done in our spare time.

Once a week we had to construe a piece of Latin prose written by some Godawful Roman no-hoper such as Livy or Cicero. At early school, which began at 7.30 a.m. after a hasty cup of tea in the Boys’ Entrance, Gad Tait, who called everyone ‘Old You’, would charmingly put us through our paces about whatever piece of Latin he had chosen. With equal charm he would exact retribution upon those who not done an adequate job. Also once a week, we had to learn a ‘saying lesson’, which involved him dictating a piece of verse which we wrote down in a flimsy blue notebook – I still have mine. It says much for Gad Tait that even today I remember most of his saying lessons. The principal one was Tennyson’s ‘Ulysses’, which we learned in three successive weeks. Others included part of A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad and Cory’s ‘Heraclitus’.

There were about thirty of us in his ‘div’ (division), and we had to recite whatever piece of verse we had been given to learn in groups of ten. Gad Tait watched closely but effortlessly, and although ten people were speaking at once, he could tell exactly who had not learned the words properly, and distributed penalties accordingly. When, just occasionally, I had written a particularly successful piece of Latin verse or whatever, he would give me a ‘show-up’. This meant that he wrote nice things at the top of my work, which I would then take to pupil room, where GWN would gratefully and happily endorse it with his initials. These were useful brownie points. Whenever Gad Tait gave anyone in M’Tutor’s a show-up, GWN, who was a more than useful cartoonist, would almost inevitably draw a picture of an old ewe on the paper. When it was handed back the next day, Gad Tait always had a chuckle at this. I can’t remember any of the other beaks I was ‘up to’ in my first half, which is a measure of Gad Tait’s skill as a schoolmaster.

Soccer and fives were the two games which occupied me in my second half, the Lent half, and then it was the summer, and cricket, which I had been longing for. I spent my first two cricketing halves in Lower Sixpenny, which was for the under fifteen-year-olds, and immediately made my greatest cricketing friend at Eton. Claude Taylor (CHT) had won a cricket Blue at Oxford, for whom he had made almost the slowest-ever hundred in the University Match, and had gone on to play for Leicestershire. He was the dearest and gentlest of men, and a wonderful coach who loved the beauty of the game more than anything. Grey-haired by the time I knew him, he had the knack of being able to explain cricket, which is not an easy game, in the most uncomplicated manner. He understood the mechanics of batting so well that he was able to dissect a stroke into a series of simple movements that when put together cohesively made not only a hugely effective stroke, in attack or defence, but a thing of beauty. He loved, above all, the beauty of the game. He taught Latin, although I never had the luck to be up to him. He also played and taught the oboe, and married the sister of Ian Peebles, a delightful Scotsman who bowled leg-breaks for Oxford, Middlesex and England. Peebles was a considerable force in a City of London wine merchants, and wrote charmingly, knowledgeably and extremely amusingly about cricket for the Sunday Times. Before the war Peebles had shared a flat in the Temple with Henry Longhurst and Jim Swanton, whom he relentlessly called ‘James’. It was a most distinguished gathering.

We began my first summer half with new-boy nets, and it was then that I caught CHT’s eye for the first time. I immediately found myself playing in ‘Select A’, the top game in Lower Sixpenny, of which he was the master-in-charge. I had a fierce competitor for the position of wicketkeeper called Julian Curtis, a wonderful all-round games player who probably lost out to me because I just had the edge in the batting stakes. In that first year, 1953, the Keeper (captain) of Lower Sixpenny was Simon Douglas Pennant, with whom I went on to play for the school and later for Cambridge, who bowled left-arm over-the-wicket at fast-medium. Edward Lane Fox was also in the side, but now that we were playing against opponents that were better-versed in the art of playing left-arm spin, ‘stumped Blofeld bowled Lane Fox’ became a less frequent entry in the scorebook. It was a memorable first summer half.

My cricketing activities went on much to the detriment of my work, and I must admit that, as at Sunningdale, my greatest ambition in the learning department was simply to get by. This attitude never received Tom’s blessing when my school reports, which were always of the ‘must try harder’ variety, were up for discussion. But as far as I was concerned, it was only cricket that mattered. If it was not Lower Sixpenny matches against other schools, it was Select A games, nets or fielding practice, and I am afraid I was the most intense competitor. The school professional at the time was Jack O’Connor, the dearest of men, who batted a time or two for England in the thirties, and played for many years for Essex. He ran the Bat Shop, just at the start of the High Street, next door to Rowland’s, one of the two ‘sock’ shops, where we guzzled crab buns and banana splits. Jack sold sporting goods, and whenever any of us went in he would give us a smiling and enthusiastic welcome. He was to become a great friend and cricketing confidant. Buying batting gloves, wicketkeeping inners or whatever from his modest emporium always involved a jolly ten-minute gossip. Once or twice CHT brought him to the Lower Sixpenny nets to watch some of us batting. Jack always gave generous, smiling encouragement. Once when I was batting he turned his arm over; so began a lifetime of misery and mystification for me as far as leg-spin and googly bowling are concerned. I still have nightmares of an umpire signalling four byes.

The winter halves were, for me, little more than an inconveniently large gap between cricket seasons. There was nothing so gloomy as going back to school towards the end of September, when the weather was gorgeous but all, or most, of the cricket grounds were strung about with goalposts. What made it even more depressing was that my return was often just a couple of days or so before my birthday. Various wrapped presents were always tucked away in the bottom of my suitcase, but opening them alone in my room between breakfast and going to chapel was a cold-blooded exercise if ever there was one. They did, however, usually contain a couple of cricket books, which helped.

In the Lent half I tried my best to impress those who mattered with my ability on the fives court and between the goalposts on the soccer pitch, but I never quite made it on either count. Soccer was run by a wonderfully bucolic former Cambridge cricket Blue called Tolly Burnett (ACB), a relation of the novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett, who added greatly to the gaiety of nations in just about everything he did. He was large, if not portly, marvellously unpunctual, rode a bicycle as if he was, with much pomp and circumstance, leading a procession of one, or perhaps rehearsing for a part in Dad’s Army, and walked with an avuncular swagger. I am not sure what Captain Mainwaring would have made of Tolly. He drove an exciting sports car, and took biology with considerable gusto, especially when it came to the more pertinent points of reproduction, in a div room just around the corner from Lower Chapel. If you stopped him in the street to ask a question, he would clatter to an uncertain halt and invariably say in somewhat breathless tones, ‘Just a bit pushed, old boy. Just a bit pushed,’ then off he’d go with a bit of a puff. What fun he was, and how we loved him. I am not sure the authorities at the school entirely agreed with us, for although he was, I believe, down to become a housemaster, the position never materialised.

Tolly captained Glamorgan during the summer holidays in 1958. The Glamorgan committee felt, as they did from time to time, that Wilf Wooller, the patriarchal figure of Welsh cricket, was too old and should be replaced. In their infinite wisdom they brought in Tolly for a trial as captain for the last eight games of the season. His highest score was 17, and the dressing room came as close to mutiny as it gets. In September he was back teaching biology at Eton, and Wooller was still the official Glamorgan captain. By the time Tolly’s moment of possible glory came, his girth would have prevented much mobility in the field, his batting was well past its prime, and his ‘Just a bit pushed, old boy’ might not have been exactly what the doctor ordered in a Glamorgan dressing room which was pure-bred Wales to its eyebrows. His charmingly irrelevant ‘Up boys and at ’em’ enthusiasm must have fallen on deaf ears. Tolly was more Falstaff than Flewellyn.

Back at Eton, before that little episode, he sadly, but entirely correctly, preferred Carrick-Buchanan’s agility between the goalposts to my own. I did however achieve the splendid job of Keeper (captain) of the second eleven. Tolly was also the cricket master in charge of Lower Club, and sadly I never had first-hand experience of the way in which he coped with that. It would not have been boring.

Keeper of the soccer second eleven, or ‘Team B’, as we proudly called ourselves, was not a particularly distinguished post, but it led to my first sortie into the world of journalism, which turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. We had a considerable fixture list, which included a game against Bradfield College’s second eleven at Bradfield. The Eton College Chronicle felt compelled to carry an account of even such insignificant encounters as this, and for some reason I was chosen to write the report. We were taken by bus to Bradfield, where we joined a mass of boys for a lunch which it would have been tempting to let go past the off-stump. Then we changed into our soccer stuff, climbed a steepish hill and found a well-used and pretty muddy football pitch. I enjoyed writing my account of the day’s events, and it duly appeared in the columns of the Chronicle. Unfortunately, it elicited a hostile response from Bradfield, who made a complaint which promptly came to the ears of Robert Birley, Eton’s large and formidable-looking, but in fact kind, rather shy and immensely able, headmaster. He was to us a remote, Genghis-Khan-like figure who hovered somewhat ominously in the background. Birley was known, unfairly in my view, as ‘Red Robert’. This merely meant that he had realised somewhat earlier than most of the school’s supporters the urgent need for change if a school like Eton was to survive. Many reactionary hands were thrown up in horror.

Anyway, one morning I found myself ‘on the Bill’, which meant that I was summoned to the headmaster’s schoolroom at midday. When I arrived, more than a trifle worried, I was told in no uncertain terms that what I had written about Team B’s midwinter visit to Bradfield was extremely offensive, and that I must without delay write a number of letters of apology. Apart from a general dressing down, I don’t think any other penalty was exacted. I still have a copy of this most undistinguished entry into the world I was to inhabit for just about the rest of my life. I have to admit that in the circumstances it may have been a little strong in places, although it is positively mild when judged by today’s standards.

The Michaelmas half in 1954 will always remain firmly in my mind, and for cricketing reasons too. England were touring Australia in the hope of hanging on to the Ashes they had won in a nerve-racking game at The Oval the previous year. There were one or two exciting newcomers in the England party, especially a fast bowler called Frank Tyson and a twenty-one-year-old called Colin Cowdrey, who was still up at Oxford. I found the whole series quite irresistible, and would tune in to the commentary from Australia under my bedclothes from about five o’clock in the morning. This was always a bit of a lottery, as the snap, crackle and pop of the atmospherics made listening a difficult business. Sometimes the line would go down altogether, and the commentary would be replaced by music from the studio in London. Those delicious Australian voices of the commentators, Johnny Moyes, Alan McGilvray and Vic Richardson, added hugely to the excitement, and John Arlott was there to add a touch of Hampshire-sounding Englishness.

First came the intense gloom at the end of November, when Len Hutton put Australia in to bat in the first Test in Brisbane, and England lost by an innings and 154 runs. Every afternoon I would rush to the corner of Keates Lane and the High Street, where the old man who sold the Evening Standard took up his post. I would thrust a few coppers at him, grab the paper, and turn feverishly to the back page. I had devoured what was for me the peerless, if at that time depressing, prose of Bruce Harris well before I got back to the Boys’ Entrance. The second Test in Sydney began in mid-December. The anxiety was enormous, and it seemed as if the end had come when Australia led by 74 on the first innings. But all was not lost, because Peter May then made a remarkable hundred, leaving Australia with 223 to win. They failed by 38 runs with Tyson taking six wickets, bowling faster than anyone can ever have bowled before. The game had a marvellous ending, with a stupendous diving leg-side catch behind the wicket by Godfrey Evans. Phew! I lived every ball. We won the third Test, in Melbourne, but I had to wait until early in the Lent half for England to make sure of the Ashes by winning the fourth Test in Adelaide. After that, to general relief at Eton, normal service was resumed.

Another diversion that winter was being prepared for my confirmation in December. At times the process was up against pretty tough competition from events in Australia, but GWN, who prepared us for the Bishop of Lincoln, was able neatly to combine events in Australia with those in Heaven. After that heavy defeat in Brisbane I was not at all sure about the Almighty, but GWN’s gentle manner and instructive way of putting things across gave meaning and relevance to the whole business of Christianity. Up until then I had felt that religion did nothing more than get in the way of things, what with endlessly having to tool off to chapel and listen to those interminable sermons. My family and one or two of my surviving godparents foregathered in College Chapel on a Saturday late in the Michaelmas half, and the Bishop of Lincoln laid his hands on our heads and turned a group of us into fully paid-up Christians. Then there was the excitement of going to my first Holy Communion the next morning, and the dreadful worry of whether or not I had got my hands the right way round when it came to the critical moment. GWN’s hard work of getting us into mid-season form for the Bishop of Lincoln was underlined and taken a stage further in the Lenten Lectures the following half, given by a notable cleric, George Reindorp, who was soon to become the Bishop of Guildford. By then England were playing slightly more frivolous cricket in New Zealand with the Ashes safely beneath their belt, and the Almighty and I were back on terms. Reindorp came across as the most delightful of men and just the right sort of Christian as he explained the issues surrounding Lent in such an unfussy way that even I thought I could understand them. Anyway, it all helped fill the gap between cricket seasons.

I had been Keeper of Lower Sixpenny in my second summer half, and went on to become Keeper of Upper Sixpenny in 1955. Upper Sixpenny, for fifteen-year-olds, was being run for the first time by a likeable new beak called Ray Parry (RHP), an immense enthusiast who during the war had played as a batsman for Glamorgan. It was one of life’s strange ironies that when, in my early seventies, I went through the divorce courts, my wife’s solicitor was none other than RHP’s son Richard. He was hellbent on delivering an innings defeat, but I think I just about saved the follow-on, if not much else.

RHP and I made great preparations for what we were sure would be a sensational season for Upper Sixpenny. But as luck would have it, David Macindoe, who ran the Eleven, and Clem Gibson, the captain of the Eleven, who actually made the decision, or at least put it into writing, summoned me to play for Upper Club, the top game in the school, from which the Eleven and the Twenty-Two (the Second Eleven) were chosen. Macindoe was another of the mildly eccentric schoolmasters Eton had a habit of producing. He had a gruff but friendly manner, a reassuring chuckle and an ever-cheerful pipe, and had opened the bowling off the wrong foot for Oxford for four years on either side of the war.

Things went well, and I donned the wicketkeeping gloves for the Eleven. I never returned to play a single game for Upper Sixpenny; nor did my old friend Edward Lane Fox, who had received a similar call to arms. At the age of fifteen it felt as near to unbelievable as it gets, especially when, early in June, I received a letter from Clem Gibson, which I still have, asking me if I would like to play against Harrow at Lord’s early in July. It was not an invitation I was likely to refuse. Can you imagine? There I was, a complete cricket nut who ate, slept and drank the game, being asked to play for two days against the Old Enemy at the Holy of Holies.

Of course, I had known by then that there was a distinct possibility the invitation would come my way, for things had been going quite well behind the stumps. But there it was in black and white. No one was more pleased than dear old Claude Taylor, with whom I had kept in close contact after leaving his clutches in Lower Sixpenny. In Upper Club nets, CHT still came to help me, standing halfway down the net and throwing an endless stream of balls at me. The stroke he taught me better than any other was the on-drive, which he considered the most beautiful in the game. When I got it right he would purr with delight. He and David Macindoe had together written a splendid book called Cricket Dialogue, about the need to maintain the traditional etiquette and standards of the game. It may be dated, but it is still well worth reading.

I shall never forget my first Eton v. Harrow match. The anticipation had been intense, and I was given a lift from Eton to Lord’s, along with Edward Lane Fox and Gus Wolfe-Murray, by Richard Burrows, a considerable middle-order batsman and a wonderful all-round games player. His father, the General, sent his Rolls-Royce – what else? – and chauffeur, and the four of us piled inside and were driven not only to Lord’s, but imperiously through the Grace Gates. What a way to enter the most hallowed cricketing portals in the world for the first time as a player. No matter what those in the know talked about in College Chapel, I felt that Heaven couldn’t be any better than this. I can still clearly remember the frisson of prickly excitement as we stopped to have our credentials checked. Yes, they even checked up on Rolls-Royces. Even today, every time I go in through the Grace Gates – and goodness knows how many times I have done so – I still get that same feeling. I remember carrying my puny little canvas cricket bag through the back door of the Pavilion, up the stairs and along the passage to the home dressing room, the one from which Middlesex, MCC and England ply their wares. After being given a cup of tea by the dressing-room attendant, we changed into our flannels. There were several formal-looking dark-brown leather couches around the walls and as I sat down on one to tie up my bootlaces it suddenly occurred to me that not a fortnight before, England had been playing the second Test against South Africa at Lord’s. In that same dressing room, sitting more or less where I was and doing precisely the same thing, would have been Denis Compton, Peter May, Ken Barrington, Tom Graveney, Godfrey Evans, Fred Trueman and the others.

We won the contest, and were generous to let Harrow get to within 34 runs of us. As far as I was concerned, the only blemish came on the second morning. We had begun our second innings on the first evening, and needed quick runs to give us time to bowl them out again. We made a good start, but then after about an hour, wickets began to fall, and there was mild panic in the dressing room. I was batting at number eight, and no sooner had I got my pads on than there came shouts of ‘You’re in, you’re in!’ I grabbed my bat and gloves and fled down the stairs, through the Long Room, down the steps and out through the gates. I strode to the Nursery End, took guard and prepared to face Rex Neame, who bowled testing off-breaks, which he was to do later on a few occasions for Kent in between his productive efforts at the Shepherd Neame Brewery. I came two paces down the pitch to my first ball, had a swing in the vague direction of the Tavern, and my off-stump went all over the place. I retreated on the interminably long return journey to the Pavilion amid applause and yells the like of which I had never heard. In the circumstances I felt I could hardly raise my bat or take off my cap, and somewhat perplexed, I continued on my way. No one much wanted to talk to me in the dressing room, so I took off my pads and things, put on my blazer and went to join Tom and Grizel in Q Stand, next to the Pavilion. When I arrived, Tom looked severely at me and said, ‘You were a bloody fool to let him get a hat-trick.’ Until then, I had had no idea it was a hat-trick – the first ever to be taken by a Harrovian in the Eton and Harrow match. Tom Pugh, who was playing that day, always says that when the hat-trick came up for discussion later, I said, ‘If I’d known it was a hat-trick I would have tried harder.’ You never know what to believe.

When I returned to Common Lane House in September 1955, Geoffrey Nickson had retired to North Wales, and Martin (‘Bush’) Forrest (MNF) had become my housemaster. It would be fair to say that we never got on. He was a charming man, but such a different type of schoolmaster to GWN that those of us who graduated from one to the other had some difficulty in getting used to the change. MNF, a large and rather heavy man, built for the scrum, was nothing if not worthy, but, at first at any rate, he lacked the quick-witted humour GWN had brought to even the trickiest of situations. I suspect MNF felt that I was the creation of his predecessor, and that as I was, at the age of fifteen, already in the Eleven, I could do with being taken down a peg or two. I found him suet pudding in comparison to the soufflé-like texture of GWN.

There is one story about Bush which illustrates my point. In the following summer half we played Marlborough at Marlborough, and won by seven or eight wickets. When we returned by bus long after lock-up, the only way into the house was through the front door. No sooner was I inside than Bush asked me how we had got on. I told him we had won, and what the scores were. He then asked me how many I had made. When I said, ‘Sixty-something not out,’ he looked at me for a moment in that stodgy way of his and said in a slightly mournful tone, ‘Oh dear,’ which was what he tended to say on almost every occasion. It hardly felt like a vote of confidence, and our relationship seldom progressed beyond a state of armed neutrality. It must have been my fault, because all of those who spent their full five years with Bush adored him. He clearly became an outstanding housemaster, and a great friend to his charges.

The 1956 cricket season at Eton was a joy. I teamed up as an opening batsman with David Barber (known as ‘Daff’), and together we formed the most amusing, successful and noisiest of opening partnerships. It was unceasing ululation as we negotiated quick singles, and seldom, initially at any rate, were we of the same opinion. We played one match against Home Park, a side largely comprised of Eton beaks. One of them was a housemaster called Nigel Wykes, a most remarkable man, who had won a cricket Blue at Cambridge, was a brilliant painter of birds and flowers, and had Agatha Christie’s grandson, Matthew Pritchard, a future captain of Eton, in his house. He was known as ‘Tiger’ Wykes, and he fancied himself as a cover point, where he was uncommonly quick with the fiercest of throws. In the course of our opening partnership, Daff pushed one ball gently into the covers and yelled, ‘Come five!’ We got them easily as Wykes swooped in and threw like a laser back to the stumps, where the middle-aged wicketkeeper was nowhere to be seen and four overthrows was the result. That year we played Winchester at Eton and came up against the fifteen-year-old Nawab of Pataudi, also called ‘Tiger’, who even at that age was in a class of his own. Like his father, he went on to captain India. He didn’t make many runs that day, but the way in which he got them told the story. As luck would have it, I caught him behind in the first innings and stumped him in the second. Sadly, that year’s Eton and Harrow match at Lord’s was ruined by rain.

I had the luck, though, to be chosen to keep wicket for the Southern Schools against The Rest for two days at Lord’s in early August. I managed to do well enough to secure the same job for the two-day game later that week, also at Lord’s, against the Combined Services, which was a terrific thrill. The Combined Services were run by two redoubtable titans of the armed forces: Squadron Leader A.C. Shirreff, the captain – Napoleon himself would have envied his ever-pragmatic leadership – and his number two, Lieutenant Commander M.L.Y. Ainsworth, who had reddish hair, a forward defensive stroke with the longest no-nonsense stride I have ever seen, and a voice that would have done credit to any quarterdeck. They had under them a bunch of young men doing their National Service, most of whom had already played a fair amount of county cricket, including Mel Ryan, who had used the new ball for Yorkshire; Raman Subba Row (Surrey and then Northamptonshire), who went on to bat left-handed for England; and Stuart Leary, a South African who played cricket for Kent and football for Charlton Athletic. Then there was Geoff Millman, who kept wicket for Nottinghamshire and on a few occasions for England; Phil Sharpe of Yorkshire and England, who caught swallows in the slips; and a few others.

We batted first, and at an uncomfortably early stage in the proceedings found that we had subsided to 72 for 6, at which point I strode to the crease. Before long Messrs Subba Row and Leary were serving up a succession of most amiable leg-breaks, and when we were all out for 221, I had somehow managed to reach 104 not out. It was quite a moment, at the age of sixteen, to walk back to the Lord’s Pavilion, clapped by the fielding side and with the assorted company of about six MCC members in front of the Pavilion standing to me as I came in. It all seemed like a dream, especially when I was told that only Peter May and Colin Cowdrey had scored hundreds for the Schools in this game. To make things even more perfect, if that were possible, Don Bradman saw my innings from the Committee Room, and sent his congratulations up to the dressing room. When we got back to Norfolk, I remember Grizel being particularly keen that I should not let it all go to my head. ‘You’re no better than anyone else, just a great deal luckier’, was how it went. I played my first game for Norfolk the next day, against Nottinghamshire Second Eleven, and made 79 in the second innings.

After that, a few people thought I was going to be rather good, but they had failed to take into account my navigational ability – or lack of it. The following 7 June (1957), in my last half at Eton, when I was captain of the Eleven, I was on my way to nets on Agar’s Plough after Boys’ Dinner when I managed to bicycle quite forcefully into the side of a bus which was going happily along the Datchet Lane, as it was then called, between Upper Club and Agar’s. I can’t remember anything about it, but Edward Scott, who ended up supervising and controlling the worldwide fortunes of John Swire’s with considerable skill, was just behind me. Rumour has it that I was talking to him over my shoulder as I sped across the Finch Hatton Bridge and into the bus.

The bus was apparently full of French Women’s Institute ladies on their way to look around Eton, which I suppose gave the event a touch of romance, but I lay like a broken jam roll in the gutter until the ambulance arrived and carted me off to the King Edward VII Hospital in Windsor. No doubt a good deal of zut alors-ing went on in the Datchet Lane. One mildly amusing by-product of this story is that I still come across Old Etonians who were around at the time, all of whom were the first or second on the scene and several of whom called the ambulance. It must have been quite a party.