Читать книгу Squeezing the Orange - Henry Blofeld, Henry Blofeld - Страница 9

ONE Grizel and Shelling Peas

ОглавлениеAccording to my mother – who had drawn the short straw at the font when she was christened Grizel – my birth was less eventful than my conception. Grizel did not muck around: she was always earthy and to the point. When my wife and I were first married, she encouraged us to waste no time in starting a family, as she felt that delay might have a discouraging effect on procreation. ‘I was lucky,’ she told me, ‘because I bred at the shake of a pair of pants’ – adding, with emphasis, ‘Which was just as well, as it was all I ever got.’ That, I hope, was not entirely fair on Tom, my father, who may not have been one of Casanova’s strongest competitors, but I am sure he had his moments. In any case, this particular pair of pants must have shaken with vigour, no doubt as part of the Christmas festivities, in 1938, as late in the evening of the following 23 September I made a swift and noisy entrance into this world. Tom will have been sitting in the drawing room dealing with a whisky and soda and The Times crossword puzzle while Dr Bennett conducted the events upstairs. I dare say this was not too arduous a production for him, for on another occasion Grizel said, ‘I found that having babies was as easy as shelling peas. I can never understand what all the fuss is about.’ So that was that.

Tom and Grizel were fiercely Edwardian in their beliefs about bringing up children, and the three of us – Anthea was ten years older than me, and John seven – had a tougher time of it than children have now. Of course we were all born with whacking great silver spoons in our mouths, but I don’t know how you can choose your parents. You’ve got to get along with what you’ve got. I’m sure Anthea and John had a stricter start to life than I did. In the thirties nannies and nurserymaids abounded, and Tom and Grizel will have been even more remote figures for the other two than they were for me. I probably had an easier time of it because during the war Nanny had to go back home to Heacham in west Norfolk to look after her sick mother. As a result, Grizel, with the help of any temporary nurserymaid she could lay her hands on, had to roll up her sleeves and do much of the dirty work herself, so she and I had a closer relationship than she did with Anthea and John. I am sure the love between parents and children was just as strong then as it is now, but in those days it was not the upfront jamboree that it has become. In fact, when you look back at it all those years ago, it seems harsh and at times almost cruel. My friends were brought up in much the same way – that was just the way things were done. I should think my parents’ generation felt that life was easy for us compared to the way they themselves had been brought up in the years immediately after Queen Victoria had died. It is all part of the ever-going evolutionary process which has brought us now to the age of the free-range child. So what seemed perfectly normal to us at the time may seem shocking from today’s considerably more relaxed perspective.

While Tom and Grizel were sticklers for keeping us on the straight and narrow, they were, in their own way, loving parents who did their best to make sure that we had as happy a childhood as possible, within the constraints of the time. They were always there for us, to help and give support, although if the fault was mine, as it usually was, they did not hesitate to say so, and seldom minced their words. For years they remained a staunch last resort, and like all offspring I went running back when in need of help, usually in the form of cash, although with only modest success, as Tom and Grizel were never that flush, and guarded their pieces of eight with a solemn rectitude.

I remember when I had reached the pocket-money stage going along to my father’s dressing room to collect my weekly dose. Sometimes I arrived a little ahead of schedule and caught him in his pants, socks and attendant sock suspenders, which was an awe-inspiring sight. It was like looking at a pole-vaulter as things went wrong. There was great excitement one morning when I found I had graduated from a twelve-sided threepenny bit (a penny of which had to go into the church collection) to a silver sixpence. The handover of the coin or coins was carried out with a formality which almost suggested that the Bank of England was involved. Tom kept his loose change in the top drawer of a tiny chest with three little drawers which perched alongside his elderly pair of ivory-backed hairbrushes, which had a strong smell of lemon from the hair oil he got from his barber. As my father made a coot look as if it was in urgent need of a haircut, this all seemed a rather pointless exercise.

While he solemnly located the appropriate piece of small change in this magical drawer, I stood by the door. I don’t think it would have occurred to Tom that he was a frightening figure to a small boy. This had something to do with his height – he stood six feet six inches tall in his stocking feet – as well as his monocle and the sock suspenders, which so fascinated me. His lighter side was harder to find than Grizel’s, and his was naturally a more formal manner. The staff, in the house and on the Home Farm, treated him with a watchful respect. When crossed or let down he could be extremely angry, and would have made common cause with some of those grumpy Old Testament prophets.

Tom regarded the ancien régime as the only possible way forward, while Grizel, if left to herself, would have been happy to allow her more extravagant natural instincts to come to the surface. While Grizel laughed in a bubbling, jolly sort of way, Tom’s merriment seemed to rumble up with more control from the bottom of his throat, and the source of his humour was often harder to fathom than his wife’s. Grizel had a strong sense of loyalty to her husband, and she was always more than aware of her position as Tom’s wife, and played the role pretty well. She was a snob, but I remember it as a snobbery as of right, rather than as a contrivance. Looking back on my parents and my childhood now, it comes to me like a black-and-white, but seldom silent, movie, and from this distance I find it highly entertaining.

The Blofelds have always been a restless lot. At some long-ago point, now lost in the mists of time, they moved from north Germany to Finland, and then shot across the North Sea with the Vikings before finally being grounded on the north Norfolk coast somewhere near what is today called Overstrand, then pushing a few miles inland and setting up shop in a small village called Sustead. Three or four hundred years whizzed by before they up-anchored again, moving twenty-odd miles south-east to Hoveton, which at that time was owned by some people called Doughty. Having a shrewd eye for the main chance, a Blofeld married a Miss Doughty, who was to become the sole surviving member of that distinguished family. Hoveton therefore soon became the Blofeld stronghold, and has remained so ever since.

Discipline – good manners, politeness, the pleases and thank yous of life – was all-important in my childhood. I can’t remember how young I was when I was first soundly ticked off for not leaping to my feet when my mother came into the room, but young enough. Dirty hands, undone buttons, sloppy speech or pronunciation, and the use of certain words were all jumped upon. Throwing sweet papers or any other rubbish out of the car window was also not popular. Goodness knows what my parents would have made of mobile telephones, and their frequent and disturbing use. Table manners were rigidly enforced. No one sat down before Grizel was in place, and you were not allowed to start eating until everyone had been served. If toast crumbs were left on a pat of butter, there was hell to pay, your napkin had to be neatly folded before you left the dining room, and you ate what was put in front of you and left a clean plate.

The nursery was presided over by Nanny Framingham, who was nothing less than a saint. Cheerful, enthusiastic and always smiling, she put up with all sorts of skulduggery. On one occasion I all but frightened her to death. My father’s guns and cartridges were kept in the schoolroom, which was next to his office. I always took a lively interest in the gun cupboard, although it was forbidden territory, and when no one was around I used to go and have a good look round. I loved the smell of the 3-in-One oil which was used to clean the guns. There was also something irresistible about the cartridges. I would steal one or two of them, take them back to the nursery and cut them up to see how they were made. One afternoon Nanny came into the room unexpectedly while I was engaged in this harmless pastime, and the sight of the gunpowder and loose shot lying all over the table terrified her – she saw us all going up in an enormous explosion, and was quick to run off and enlist help. Within a matter of minutes Tom burst into the nursery, looking and sounding a good deal worse than the wrath of God. My cartridge-cutting activities came to an immediate halt, and I was probably sent up to my bedroom for an indefinite period, possibly with a clip over the ear or a smack on the bottom as well. Corporal punishment was always on the menu.

The schoolroom lived up to its name, for it was there, along with my first cousin, Simon Cator, and Jane Holden, an unofficial sister and lifelong friend who lived nearby at Neatishead, that we were given the rudiments of an education by the small, bespectacled, virtuous, austere and humourless Mrs Hales. I often wonder, looking back, what she and Mr Hales – who I’m not sure I ever met – got up to in their spare time. Not a great deal, I should think. They lived at Sea Palling, and she turned up each morning rather earlier than was strictly necessary in her elderly Austin Seven, which, in spite of often making disagreeable and unlikely noises, kept going for many years. On the occasions when we got the better of Mrs Hales and were rather noisily mobbing her up, the door from the schoolroom into my father’s office would burst open, Tom’s thunderous face would appear, and order would be instantly restored. Our lessons were fun, and we learned to read and write and do some basic arithmetic. Mrs Hales must have done a good job, because when I went away to boarding school I found I was able to hold my own.

Tom was an imposing figure. In addition to his height, he had a small moustache which was more a smattering of foliage on his upper lip than anything else. He said he grew it to avoid having to shave his upper lip, which, as he used a cut-throat razor for most of his life, may have been a tricky operation. He had a huge nose, which he blew and sneezed through with considerable venom while applying a large and colourful silk handkerchief to the enormous protuberance. His monocle hung from a thread around his neck, and dangled down in front of his tie. This was impressive, unless, as a small boy, I was summoned to his office for my school report to be discussed. I would tread apprehensively down the long corridor, past the cellar and the game larder, and through the schoolroom for this ghastly meeting. It never had a happy outcome, because away from the games field I was an out-and-out slacker. Tom, sitting behind his desk while I perched apprehensively on the leather bum-warmer around the fireplace, would read out all the hideous lies those wretched schoolmasters had written about me. Not only that, he would believe every single word of them. Both he and Grizel invariably took the side of my persecutors, something it seems parents seldom do today. Having read out the details of whichever crime it was that I was supposed to have committed, there would be a nasty tweak of the muscles around his right eye. The monocle would fall down his shirt front, indicating that it was my turn to go in to bat. I was then invariably bowled by a ball I should have left alone.

When I had reached the age when I was more or less house-trained, I was allowed to join my parents in the drawing room for an hour or so before going to bed. Nanny would open the drawing-room door in the hall to let me in, and Grizel would always greet me with the words, ‘Hello, ducky.’ I loved these visits, for Grizel usually had something fun or interesting for me to do. She taught me card games, starting with a simple two-handed game called cooncan. I graduated from that to hearts, which needed four people, and piquet, which I played with Tom. Grizel also taught me the patiences she would play while Tom was reading and I loved the one called ‘trousers’. We played Ludo and Cluedo, and occasionally Monopoly. Tom would make up the numbers for these, too, but I don’t think Monopoly was really his sort of thing. When he had bought the Old Kent Road he was never quite sure what to do with it.

When I was a touch older, Tom would read aloud to me, and I have always been eternally grateful for this. I think he started me off with Kipling’s Just So Stories – I adored ‘The Elephant’s Child’. I know I have never laughed at any story more than Mr Jorrocks’s adventures in R.S. Surtees’ Handley Cross. Tom was brilliant at all the different accents: his imitation of huntsman James Pigg’s Scottish vowels was special. Then there were John Buchan’s Richard Hannay books, The Thirty-Nine Steps and so on, and Dornford Yates’s stories about Jonathan Mansell and the others discovering treasure in castles in Austria. I was introduced to Bulldog Drummond, Sherlock Holmes and Dorothy Sayers’ detective Lord Peter Wimsey who became a great hero of mine. Tom adored P.G. Wodehouse, and wanted to read me some of the Jeeves books, but Grizel couldn’t stand them, and they stayed on the shelves. We all have awful secrets which we hope will never slip out. One of mine is that I had a mother who didn’t like Wodehouse or Gilbert and Sullivan. This still surprises me, because I would have thought Grizel would have enjoyed the fantasy world of Wodehouse. Tom’s reading would finish in time for the weather and the six o’clock news. After the news headlines, Tom would invariably tell Grizel to turn off the wireless. He dismissed the rest of the news as ‘gossip’. Then it was drinks time for them and bedtime for me.

I am sure Tom never played cricket, judging from his one performance in the fathers’ match when I was at Sunningdale. But he enjoyed the game, and each summer he and two of his friends, Reggie Cubitt (who was his cousin) and Christo Birkbeck, would go up to London for the three days of the Gentlemen v. Players match at Lord’s. They stayed at Boodle’s, and I dare say it was as close as any of them ever came to letting their hair down, which probably meant no more than having a second glass of vintage port after dinner. It is unlikely that they would have paid a visit to the Bag o’Nails after that. Reggie and Christo were a sort of social barometer for Tom and Grizel. If, in the years I still lived at home, I was intending to embark upon some rather flashy adventure, Grizel would caution me by saying, ‘What would Reggie and Christo think?’

Just before the end of the war there were some German prisoners-of-war working on the farm at Hoveton. It was said that if Germany had played cricket it might never have gone to war, so it was ironic that these PoWs were put to work turning a part of the old parkland up by the little round wood at Hill Piece into a wonderfully picturesque cricket ground. The village team, Hoveton and Wroxham, played there, and for several years later on I organised a two-day game in September between the Eton Ramblers and the Free Foresters, which was highly competitive and great fun. It was a lovely ground in a wonderful setting, but sadly it has disappeared for a part of it has now been planted over with trees.

Tom could be great value. He had a wonderful turn of phrase. He and Grizel would go to bed every night at around ten o’clock. Sitting in the drawing room at the Home Farm, or later in the hall at Hoveton House, he would shut his book, half stretch, and say, ‘Well, I think it’s time for a bit of a lie-down before breakfast.’ Another splendid offering would come when a visitor was over-keen to make a favourable impression. When asked what he thought about whoever it was when he had gone, Tom would say, ‘Awfully nice. I do just wish he wouldn’t fart above his arsehole quite so much.’

There was one incident when I was young for which I never forgave Tom. I always ate with Nanny in the nursery, but I was allowed to have lunch in the dining room with my parents on the last full day of the school holidays – I was sent to boarding school at Sunningdale when I was seven and a half. And not only that: I was allowed to choose the pudding. One year Grizel came by a stock of tinned black cherries, and whenever I tasted them I didn’t think I would ever get much closer to heaven. Goodness knows where she found them. Anyway, on this occasion I said I would like some black cherries as the pud, and to my surprise my wish was granted. We sat down to lunch at one o’clock – mealtimes were immutable, and if you were late it was considered to be a major crime. Tom carved the cold beef. They had cold roast beef six days a week, or so it seemed, and to ring the changes, hot roast beef on Sundays. A woman called Joan, who ferried these things around in the dining room, put my plate in front of me, and when everyone had been served, we tucked in. Our empty plates were collected, and then it was time for the cherries.

They were brought in by Joan on a large brown tray, and put down on the sideboard. As well as the big glass bowl brimful of cherries, there was another full of junket, that ghastly milk jelly which I detested with a passion. Tom got up to serve us, and in addition to a pretty useful pile of cherries, I was given two big spoonfuls of junket. We were brought up to ‘eat level’, which meant that junket and cherries had to be eaten together. But on this occasion I threw caution to the winds and, feigning great enthusiasm, got stuck into the junket, which I finished in record time. My undisturbed pile of cherries was now gleaming up at me from my plate. The next five minutes looked promising. But Tom had been watching.

‘Joan,’ he said, for she was still lurking by the sideboard, ‘Master Henry’ – I was always Master Henry as far as the staff were concerned – ‘clearly does not like his cherries. Will you please remove them.’ Which is what she did, and I have only just stopped crying. Life could be bloody unfair, or so it seemed. But I had broken the rules.

In the fifties Tom bought an old Rolls-Royce from a chap who lived in the neighbouring village of Coltishall. It was a bespoke model, and was thought to be one of the last Rolls made with a red ‘RR’ on the front of the bonnet – the change to black was made in 1933, for aesthetic reasons. It was a huge, pale-grey car with a soft roof which never came off, as far as I know. There was a window between the back and the front seats which could be wound up by those in the back so the chauffeur couldn’t do any eavesdropping. As Tom always drove it himself this window remained down and was not to be touched. I thought it was the sexiest car ever, because it had no fewer than three horns. One was a gentle toot for warning an old woman against crossing the road; the next was a bit stronger, in case she had already started; and the third was a klaxon which yelled at her just as she was disappearing under the wheels. ‘Bloody fool,’ Tom would mutter after he had pressed it.

My father used the Rolls as his main car for at least ten years, and it always caused my school chums great amusement when he drove it down to Eton. He was the Chairman of the Country Gentleman’s Association, and the number plate was CG 1000, so he was known by my friends as ‘Country Gent One Thousand’. As it was such a big car he sometimes had difficulty negotiating the smaller streets in London, but it was such an imperious-looking machine that almost everyone got out of the way. If not, there was much hooting, which occasionally got to the klaxon stage. Although parking in those days was a great deal easier than it is now, it still presented problems in the busy parts of London. But Tom, whose appearance was nothing if not distinguished, had the answer to that. He would drive slowly down, say, Bond Street, and when he saw two coppers walking along the pavement – as one did in those far-distant days – he would stop the car, get out and shut the door, saying to the nearest one, ‘Officer, look after my car for me. I shall only be about ten minutes,’ and walk off. When he returned they would indeed be looking after his car. I always wondered who they thought he was.

In many ways Grizel was the antithesis to Tom. She was short, although there was a fair bit of her in the horizontal sense, and she packed a pretty good punch. She went around like a battleship under full steam, with a siren to match. A woman of the most forthright and damning opinions, with a fund of common sense, she did not tolerate what she described as nonsense in any shape or form, and was quick to spot anything remotely bogus. In turn, you had to accept her as she was. She was very bright, and had a marvellous sense of humour. She was a reasonably devout Christian, and church – where Tom read the lessons, and was joint patron of the living together with the Bishop of Norwich – was an essential part of Sundays. As a child, I always felt the time spent in church could have been more usefully employed. Grizel, sensing my objections, would say to me, ‘You’ve had a lovely week. Now you can spend an hour saying thank you.’ She was fond of God, but dealt with him entirely on her own terms. When they eventually met I should think a good deal of finger-wagging of the ‘now, look here’ sort will have gone on.

In 1956 we moved up the drive from the Home Farm to Hoveton House. There was a dinner party soon afterwards, and one of my parents’ friends who came along was what people today would refer to as a born-again Christian. In those days he was known as a God-botherer. He loved to get stuck into his neighbour’s ribs and start banging on about God. While she was all for the general idea of converting people, Grizel felt there was a time and place for everything, and that a dinner party was not remotely a conversional occasion, so she sat him next to her to avoid the danger. But after dinner, as was the custom, the ladies left the room to powder their noses or whatever, leaving the chaps to drink their port before they all joined forces later on in the drawing room. When this moment arrived, our God-botherer found himself sitting on a sofa on the other side of the fireplace from Grizel. After a few minutes she noticed that he was giving his neighbour, a good-looking girl, a fearful going over about the Almighty. She coughed and generally registered short-range disapproval. The God-botherer, realising that he had got it wrong, stopped in mid-sentence and, leaning forward towards Grizel with his elbows on his knees, asked in a surprised voice, ‘But surely, Grizel, you believe in Our Lord Jesus Christ?’ Grizel narrowed her eyes, leaned back a fraction and delivered a stinging rebuke: ‘Never in the drawing room after dinner.’ Which was game, set and match.

Every summer for the last five years of their lives together, before my father put his cue in the rack in 1986, my parents would go for a holiday on a barge on the French canals. It was a fearfully upmarket barge, without a punt pole in sight. At six o’clock each evening they had a glass of champagne on deck, then went up to their cabin to change for dinner, which meant a dinner jacket for Tom and a long skirt for Grizel, before re-emerging to have another glass of champagne. There were always a number of Americans on board who helped make up the numbers. Grizel was suspicious of Americans. She felt that they bounced rather too much. One evening the two of them went up to change for dinner, came down suitably attired and tackled their second glasses of champagne. They had hardly begun when from stage right, a short, middle-aged American in ‘perfectly ghastly rubber shoes’ came bouncing across the deck to Grizel with his arms outstretched, saying in a loud voice, ‘Hi, my name’s Jim. What’s yours?’ This was too much for Grizel who took a step back, mentally at any rate, drew herself up to her full five feet six and a half inches and said in a menacingly firm voice, ‘That, I am afraid, is a private matter, but you may call me Mrs Blofeld.’ I think Bertie Wooster’s Aunt Dahlia might well have come up with both those answers.

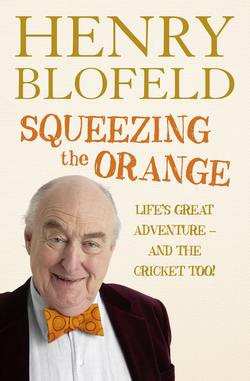

I have found that the older I become, the more I look back to my origins and see it all in a different perspective even from fifteen years ago. If I seem a little too critical of my parents, it is with my tongue firmly in my cheek. I feel now, more than ever, that the most surprising thing is that these things happened at all. Hoveton was terrific fun, and it would not have been so enjoyable if Tom and Grizel had been other than they were. Their strong personalities were stamped all over the place. And not only that: although they were never particularly flush with cash, they gave all three of us a wonderful education. Anthea went on to become a doctor, and John, who inherited Tom’s wonderful speaking voice, became a distinguished High Court judge. Meanwhile, I scrabbled around in the press and the broadcasting boxes of the cricketing world. Then when old age was taking hold I began to tread the boards, in the hope of making a few people laugh in any theatre brave enough to take me on, although I fear I may have bored many of them to tears.

We now live in an age when much that I never even dreamt about when I was young has come about. The world of Tom and Grizel has been relegated to the stuff of fairy stories, yet at the time it was as natural as night following day. There was no other game in town for those on either side of the green baize door, and we all got on with it. As a child I had a great relationship with everyone who worked for my parents, both in the house and on the farm, except for Mrs Porcher, our cook. She was a small woman with a shrill voice, and although she was no doubt a dab hand at the kitchen stove, as far as I was concerned she never seemed to blur any issue with goodwill. She didn’t exactly take on my parents, but there was sometimes a curtness to her manner that did not always bring out the best in Grizel. I remember Mrs Porcher going into the drawing room after breakfast, notepad in hand, ready for Grizel to order the food for lunch and dinner that day. Mrs Porcher always had the sense to realise that if she entered into a battle of wills with Grizel there could only be one outcome, while Grizel knew that it would be an awful bore to have to find another cook. As a result, there existed a continuous state of armed neutrality between them. When Mrs Porcher eventually returned permanently into the no doubt grateful arms of Mr Porcher, cooks came and went at a fair pace, until the redoubtable Mrs Alexander took over.

My early years must have shaped the initial hard core of me, which I hope has been smoothed down a bit by the subsequent journey through the mainly self-imposed rough seas of life. In many ways, of course, memory is selective, but there is no doubt that the family estate at Hoveton was an enchanting place in which to have been brought up. Over a great many years it had grown smaller as those in charge of it had seen fit to sell off pieces of land – mostly, I expect, to raise a bit of lolly. But the nucleus that still remained when I was young was heaven for a small boy. Two of the Norfolk Broads, Hoveton Great Broad and Hoveton Little Broad, were within its boundaries, and there were many acres of exciting marshland, with dykes and dams and all manner of birdlife, from ducks and geese to bitterns, swans, hawks and masses of smaller varieties. Grizel was passionate about the local flora and fauna, and would teach me the names of butterflies, birds, insects, trees and wildflowers. Sadly I have forgotten most of them, which would have made her very cross. Sometimes she would find a swallowtail butterfly chrysalis in the reeds on the marshes. This would be brought home and put in a cage in the drawing room, and some time later the most beautifully coloured butterfly you could imagine would emerge. Before it could damage those magical wings by fluttering against the sides of the cage, it would be released into the marshes to fend for itself. Sadly, over the years swallowtails became increasingly scarce and by now have probably completely disappeared : I should think the last one to be reared at home was sometime in the fifties.

For a time Grizel collected Siamese cats, which lived in a long wooden hut in the farmyard at the Home Farm. She won many prizes with them. The silver spoons with which we stirred our coffee after lunch all had the letters ‘SCC’ (Siamese Cat Club) emblazoned on their handles. She also went through a Japanese bantam stage, during which, intermingled with a fluffy collection of white Silkies, they trawled all over the farmyard, not always to Tom’s delight.

Another phase of her life was devoted to Dutch rabbits. These again won prizes, and were kept in the shed that had once been the home of the Siamese cats. There was also an impressive herd of pedigree Shorthorns, which, amid great excitement, won all sorts of prizes over the years at the Royal Show. Grizel was closely involved with the breeding of the cattle, and would go down to the dairy farm almost every day. With the head cowman in tow she would have a look at whatever animals she was particularly interested in, and cast an eye over any new calves. If need be, she was more than happy to roll up her sleeves and help with a difficult birth. When I was very young she would talk for ages to Birch, who was the head cowman, and later to his successor, Pressley, whom I found more fun. I remember Grizel and Pressley constantly hatching plots to convince Tom of the necessity of buying a new bull, or a couple of heifers, or whatever. The dairy was always a fruitful playground for me. I loved watching the cows being milked, and then the milk being separated from the cream. There was one occasion when I eluded Grizel and Pressley and walked into one of the cow sheds when a heifer was in the act of being served by a bull. After I had been dragged out Pressley was embarrassed, but Grizel, who took these things in her stride, said to me, ‘You’ll find out more about that one day, darling, but not just yet.’ This left me deeply curious, but I knew better than to question her. She had drawn a line under the subject for the time being.

Grizel, with her familiar stride, which was more a purposeful walk than a strut, was forever busying herself around the house, the garden and the farmyard. She made the life of the gardener, Walter Savage, confusing and difficult as she issued instructions over her shoulder while he struggled along in her wake. Savage, as we called him, was thin, about medium height, with a white moustache, a good First War record, and a huge and frightening wife who put the fear of God into poor old Savage. They lived in one half of the charming Dutch gabled cottage at the bottom of the Hoveton House garden. When I was a bit older, Savage would drive me and some friends in my mother’s car to the Norwich speedway track, where the home team were pretty high in the national pecking order. Ove Fundin, a five-time world champion from somewhere in Scandinavia, was a name I shall never forget; nor that thrilling smell of petrol fumes and burning rubber as the riders strove to steer their brakeless bikes around corners. On other occasions Savage ferried several of us to the Yarmouth Fun Fair, where the bumper cars, the ghost train and the fish and chips were all irresistible.

When I was a child the farm, which had been whittled down over the years to about 1,300 acres, had become principally a fruit farm. There were an awful lot of people employed to tend to its needs. When I was old enough I used to help the wives of the farmworkers pick the fruit. There was the excitement of being paid sixpence by Herbert Haines for a basket of Victoria plums and a punnet of raspberries. This was a useful supplement to my pocket money. Herbert, short and indomitably cheerful, wearing a perilously placed felt hat, loved his cricket and presided over the fruit picking.

The farm manager, the slightly austere, bespectacled and white-haired Mr Grainger, tootled about the place in his rather severe-looking car. I was extremely careful of him, for I knew that anything I got up to would go straight back to Tom. Mr Grainger had a small office in the Home Farm yard which I avoided like the plague. In fact I think it was a mutual avoidance. As far as I was concerned, Mr Grainger, who lived in a small house down the drive, was always hard work, and if he had a lighter side, I never found it. My father’s office was presided over by the ebullient, bouncing and eternally jolly, but not inconsiderable, figure of Miss Easter, a local lady from Salhouse who was a close ally of Nanny’s. I loved it when she paid us a visit in the nursery. ‘Miss Easter’ was a tongue-twister for the young, and she was known affectionately by all of us, including Grizel, as ‘Seasser’, although Tom never bent from ‘Miss Easter’. I suppose she must have had a Christian name, but I can’t remember it. Sadly for us, she left Hoveton when approaching middle age, and became Mrs Charles Blaxall. He was a yeoman farmer, and they lived somewhere between Hoveton and Yarmouth. I used to go with Nanny to visit her in her new role as a farmer’s wife. She remained the greatest fun, always provided goodies and was one of the real characters of my early life. I can hear her cheerful, echoing laughter even now.

Freddie Hunn, a small man with the friendliest of smiles, was in charge of the cattle feed, which was ground up and mixed in the barn across the yard from my father’s office. I loved to go and help Freddie. There was a huge mixer, which was almost the height of the building. All the ingredients were thrown in at the top, mixed, and then poured into sacks at the bottom. The barn had a delicious, musty smell. Freddie’s other role was to look after the cricket ground at the other end of the farmyard, through the big green gate and up the long grassy slope to Hill Piece. After his day in the barn had finished he would go up to the ground and get to work with the roller or mower or whatever else was needed. The day before a match between Hoveton and Wroxham and one of the neighbouring villages, out would come the whitener, and the creases would be marked. I found it all fascinating, and Nanny could hardly get me back to the house in time for a bath on Friday evenings.

Freddie was a great Surrey supporter, while I was passionate about Middlesex and Compton and Edrich. But Freddie always thought he had trumped my ace when he turned, as he inevitably did, to Jack Hobbs. Freddie’s wife, the large, smiling Hilda Hunn, supervised the delicious cricket teas, and sometimes allowed me a second small cake in an exciting, coloured paper cup.

One of my favourite farmworkers was Lennie Hubbard, whom we all, including my father, called by his Christian name. I never discovered why or how such distinctions were made: why most of the workers on the farm were known by their surnames, while Freddie, Lennie and one or two others went by their Christian names. Lennie was tall, and had been born in the Alms Houses in Lower Street, the rather upmarket name for the lane that ran past these cottages down to the marshes. Once, a great many years earlier, that lane had been part of the main road from Norwich to Yarmouth, which had originally gone past the front of Hoveton House. During the Second World War Lennie had been taken prisoner by the Germans, but had managed to escape – perhaps it was his gallantry that had caused his Christian name to be used. Tom always enjoyed talking to Lennie, and regarded him as one of his best and most faithful employees. There was an irony in that, as Lennie told me much later, long after Tom had died, he and one or two others, for all their outward godliness, had been diehard poachers. He told me, with a broad smile, of an occasion when one day my father had suddenly appeared around the corner of a hedge and spoken to him for ten minutes. Under his greatcoat Lennie was hiding his four-ten shotgun and a recently killed cock pheasant. I dare say he never came closer to losing both his job and his Christian-name status.

Shooting was another highlight of my early life. I fired my first shot when I was nine, missing a sitting rabbit by some distance. I am afraid I was the bloodthirstiest of small boys, and I have loved the excitement and drama of shooting for as long as I can remember.

Tom used to arrange six or seven days’ shooting a year with never more than seven guns. They would kill between one and two hundred pheasants and partridges in a day. As a small boy I found these days hugely exciting. Then there was the early-morning duck flighting on the Great Broad. This was always a terrific adventure, getting up in the dark and eating bread and honey and drinking Horlicks in the kitchen before setting off by car for the Great Broad boathouse soon after five o’clock in the morning. There was also the evening flighting on the marshes, when each of us stood in a small butt made of dried reeds. This was also thrilling, and of course by the time we got home night had set in.

Carter was the first gamekeeper I remember. He was a small, rather gnarled man with a lovely Norfolk voice. Apart from looking after the game and trying to keep the vermin in check, his other job each morning was to brush and press the clothes my father had worn the day before. He did this on a folding wooden table on the verandah by the back door. When he had done this, if I asked politely and he was in an obliging mood, he would come out to the croquet lawn and bowl at me for a few minutes. I had to tread carefully with Carter. I think he was the first person ever to bowl overarm to me with a proper cricket ball. Sometimes I hit him into the neighbouring stinging nettles, which ended play for the day, for his charity did not extend to doing the fielding off his own bowling. Carter was the village umpire during the summer. I’m not sure about his grasp of the laws of the game, but you didn’t question his decisions – you merely moaned about them afterwards. When Carter retired he was succeeded by Watker, a brilliant clay-pigeon shot and, to me, a Biggles-like figure; and then by Godfrey, the nicest of them all. I would spend a huge amount of time with the keepers during the holidays. Once or twice I looked after Godfrey’s vermin traps when he had his holiday. Sadly, neither Watker nor Godfrey had a clue how to bowl, but Nanny, who was up for most things, would bowl to me on the croquet lawn. Her underarm offerings often ended up in the nettles, and being the trouper she was, she would dive in after them, and usually got nastily stung.

It was a fantastic world in which to be brought up. Looking back on it, it was quite right that I should have been taught how to use it and respect it. I can almost feel myself forgiving Tom for those cherries. In a way it was sad when my full-time enjoyment of Hoveton came to an end. But when I was seven and a half I was sent away to boarding school at Sunningdale, almost 150 miles away, which may now seem almost like wanton cruelty, but was par for the course in those days. When I was young, all I wanted to do was to grow older, and going away to school seemed a satisfactory step in the right direction.