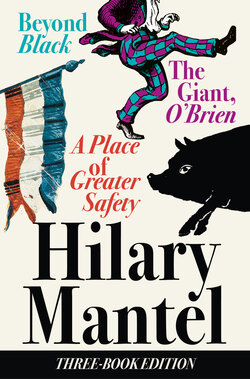

Читать книгу Three-Book Edition - Hilary Mantel - Страница 21

IV. A Wedding, a Riot, a Prince of the Blood (1787–1788)

ОглавлениеLUCILE has not said yes. She’s not said no. She’s only said, she’ll think about it.

ANNETTE: her first reaction had been panic and her second rage; when the immediate crisis was over and she had not seen Camille for a month, she began to curtail her social engagements and to spend the evenings by herself, worrying the situation like a dog with a bone.

Bad enough to be deemed seduced. Worse to be deemed abandoned. And to be abandoned for one’s adolescent daughter? Dignity was at its nadir.

Since the King had dismissed his minister Calonne, Claude was at the office every evening, drafting memoranda.

On the first night, Annette had not slept. She had tossed and sweated into the small hours, plotting herself a revenge. She had thought that she would somehow force him to leave Paris. By four o’clock she could no longer bear to remain in her bed. She got up, pulled a wrap about her shoulders, walked through the apartment in the dark; walked barefoot, like a penitent, for the last thing she wanted was to make any noise at all, to wake her maid, to wake her daughter – who was sleeping, no doubt, the chaste and peaceful sleep of emotional despots. When dawn came she was shivering by an open window. Her resolution seemed a fantasy or nightmare, a monstrous baroque conceit dreamed by someone other than herself. Come now, it’s an incident, she said to herself: that’s all. She was left, then as now, with her grievance and her sense of loss.

Lucile looked at her warily these days, not knowing what was going on in her head. They had ceased to speak to each other, in any sense that mattered. When others were present they managed some vapid exchanges; alone together, they were mutually embarrassed.

LUCILE: she spent all the time she could alone. She re-read La Nouvelle Heloïse. A year ago, when she had first picked up the book, Camille had told her he had a friend, some odd name, began with an R, who thought it the masterpiece of the age. His friend was an arch-sentimentalist; they would get on well, were they to meet. She understood that he himself did not think much of the book and wished a little to sway her judgement. She remembered him talking to her mother of Rousseau’s Confessions, which was another of those books her father would not allow her to read. Camille said the author lacked all sense of delicacy and that some things were better not committed to paper; since then she had been careful what she wrote in her red diary. She recalled her mother laughing, saying you can do what you like I suppose as long as you retain a sense of delicacy? Camille had made some remark she barely heard, about the aesthetics of sin, and her mother had laughed again, and leaned towards him and touched his hair. She should have known then.

These days she was remembering incidents like that, turning them over, pulling them apart. Her mother seemed to be denying – as far as one could make out what she was saying at all – that she had ever been to bed with Camille. She thought her mother was probably lying.

Annette had been quite kind to her, she thought, considering the circumstances. She had once told her that time resolves most situations, without the particular need for action. It seemed a spineless way to approach life. Someone will be hurt, she thought, but every way I win. I am now a person of consequence; results trail after my actions.

She rehearsed that crucial scene. After the storm, a struggling beam of late sun had burnished a stray unpowdered hair on her mother’s neck. His hands had rested confidingly in the hollow of her waist. When Annette whirled around, her whole face had seemed to collapse, as if someone had hit her very hard. Camille had half-smiled; that was strange, she thought. For just a moment he had held on to her mother’s wrist, as if reserving her for another day.

And the shock, the terrible, heart-stopping shock: yet why should it have been a shock, when it was – give or take the details – just what she and Adèle had been hoping to see?

Her mother went out infrequently, and always in the carriage. Perhaps she was afraid she might run into Camille by accident. There was a tautness in her face, as if she had become older.

MAY CAME, the long light evenings and the short nights; more than once Claude worked right through them, trying to lay a veneer of novelty on the proposals of the new Comptroller-General. Parlement was not to be bamboozled; it was that land tax again. When the Parlement of Paris proved obdurate, the usual royal remedy was to exile it to the provinces. This year the King sent it to Troyes, each member ordered there by an individual lettre de cachet. Exciting for Troyes, Georges-Jacques d’Anton said.

On 14 June he married Gabrielle at the church of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois. She was twenty-four years old; waiting patiently for her father and her fiancé to settle things up, she had spent her afternoons experimenting in the kitchen, and had eaten her creations; she had taken to chocolate and cream, and absently spooning sugar into her father’s good strong coffee. She giggled as her mother tugged her into her wedding dress, thinking of when her new husband would peel her out of it. She was moving on a stage in life. As she came out into the sunshine, hanging on to Georges’s arm harder than convention dictated, she thought, I am perfectly safe now, my life is before me and I know what it will be, and I would not change it, not even to be the Queen. She turned a little pink at the warm sentimentality of her own thoughts; those sweets have jellified my brain, she thought, smiling into the sun at her wedding guests, feeling the warmth of her body inside her tight dress. Especially, she would not like to be the Queen; she had seen her in procession in the streets, her face set with stupidity and helpless contempt, her hard-edged diamonds flashing around her like naked blades.

The apartment they had rented proved to be too near to Les Halles. ‘Oh, but I like it,’ she said. ‘The only thing that bothers me are those wild-looking pigs that run up and down the street.’ She grinned at him. ‘They’re nothing to you, I suppose.’

‘Very small pigs. Inconsiderable. But no, you’re right, we should have seen the disadvantages.’

‘But it’s lovely. It makes me happy; except for the pigs, and the mud, and the language that the market ladies use. We can always move when we’ve got more money – and with your new position as King’s Councillor, that won’t be very long.’

Of course, she had no idea about the debts. He’d thought he would tell her, once life settled down. But it didn’t settle, because she was pregnant – from the wedding night, it seemed – and she was quite silly, mindless, euphoric, dashing between the café and their own house, full of plans and prospects. Now he knew her better he knew that she was just as he’d thought, just as he’d wished: innocent, conventional, with a pious streak. It would have seemed hideous, criminal to allow anything to overshadow her happiness. The time when he might have told her came, passed, receded. The pregnancy suited her; her hair thickened, her skin glowed, she was lush, opulent, almost exotic, and frequently out of breath. A great sea of optimism buoyed them up, carried them along into midsummer.

‘MAÎTRE D’ANTON, may I detain you for a moment?’ They were just outside the Law Courts. D’Anton turned. Hérault de Séchelles, a judge, a man of his own age: a man seriously aristocratic, seriously rich. Well, Georges-Jacques thought: we are going up in the world.

‘I wanted to offer you my congratulations, on your reception into the King’s Bench. Very good speech you made.’ D’Anton inclined his head. ‘You’ve been in court this morning?’

D’Anton proffered a portfolio. ‘The case of the Marquis de Chayla. Proof of the Marquis’s right to bear that title.’

‘You seem to have proved it already, in your own mind,’ Camille muttered.

‘Oh, hallo,’ Hérault said. ‘I didn’t see you there, Maître Desmoulins.’

‘Of course you saw me. You just wish you hadn’t.’

‘Come, come,’ Hérault said. He laughed. He had perfectly even white teeth. What the hell do you want? d’Anton thought. But Hérault seemed quite composed and civil, just ready for some topical chat. ‘What do you think will happen,’ he asked, ‘now that the Parlement has been exiled?’

Why ask me? d’Anton thought. He considered his response, then said: ‘The King must have money. The Parlement has now said that only the Estates can grant him a subsidy, and I take it that having said this they mean to stick to it. So when he recalls them in the autumn, they will say the same thing again – and then at last, with his back to the wall, he will call the Estates.’

‘You applaud the Parlement’s victory?’

‘I don’t applaud at all,’ d’Anton said sharply. ‘I merely comment. Personally I believe that calling the Estates is the right thing for the King to do, but I am afraid that some of the nobles who are campaigning for it simply want to use the Estates to cut down the King’s power and increase their own.’

‘I believe you’re right,’ Hérault said.

‘You should know.’

‘Why should I know?’

‘You are said to be an habitué of the Queen’s circle.’

Hérault laughed again. ‘No need to play the surly democrat with me, d’Anton. I suspect we’re more in sympathy than you know. It’s true Her Majesty allows me the privilege of taking her money at her gracious card table. But the truth is, the Court is full of men of good will. There are more of them there than you will find in the Parlement.’

Makes speeches, d’Anton thought, at the drop of a hat. Well, who doesn’t? But so professionally charming. So professionally smooth.

‘They have good will towards their families,’ Camille cut in. ‘They like to see them awarded comfortable pensions. Is it 700,000 livres a year to the Polignac family? And aren’t you a Polignac? Tell me, why do you content yourself with one judicial position? Why don’t you just buy the entire legal system, and have done with it?’

Hérault de Séchelles was a connoisseur, a collector. He would travel the breadth of Europe for a carving, a clock, a first edition. He looked at Camille as if he had come a long way to see him, and found him a low-grade fake. He turned back to d’Anton. ‘What amazes me is this curious notion that is abroad among simple souls – that because the Parlement is opposing the King it somehow stands for the interests of the people. In fact, it is the King who is trying to impose an equitable taxation system – ’

‘That doesn’t matter to me,’ Camille said. ‘I just like to see these people falling out amongst themselves, because the more they do that the quicker everything will collapse and the quicker we shall have the republic. If I take sides meanwhile, it’s only to help the conflict along.’

‘How eccentric your views are,’ Hérault said. ‘Not to mention dangerous.’ For a moment he looked bemused, tired, vague. ‘Well, things won’t go on as they are,’ he said. ‘And I shall be glad, really.’

‘Are you bored?’ d’Anton asked. A very direct question, but as soon as it popped into his head it had popped out of his mouth – which was not like him.

‘I suppose that might be it,’ Hérault said ruefully. ‘Though one would like to be – you know, more lofty. I mean, one likes to think there should be changes in the interest of France, not just because one’s at a loose end.’

Odd, really – within a few minutes, the whole tenor of the conversation had changed. Hérault had become confiding, dropped his voice, shed his oratorical airs; he was talking to them as if he knew them well. Even Camille was looking at him with the appearance of sympathy.

‘Ah, the burden of your wealth and titles,’ Camille said. ‘Maître d’Anton and I find it brings tears to our eyes.’

‘I always knew you for men of sensibility.’ Hérault gathered himself. ‘Must get off to Versailles, expected for supper. Goodbye for now, d’Anton. You’ve married, haven’t you? My compliments to your wife.’

D’Anton stood and looked after him. A speculative expression crossed his face.

THEY HAD STARTED to spend time at the Café du Foy, in the Palais-Royal. It had a different, less decorous atmosphere from M. Charpentier’s place; there was a different set of people. And one thing about it – there was no chance of bumping into Claude.

When they arrived, a man was standing on a chair declaiming verses. He made some sweeping gestures with a paper, then clutched his chest in an agony of stage-sincerity. D’Anton glanced at him without interest, and turned away.

‘They’re checking you out,’ Camille whispered. ‘The Court. To see if you could be any use to them. They’ll offer you a little post, Georges-Jacques. They’ll turn you into a functionary. If you take their money you’ll end up like Claude.’

‘Claude has done all right,’ d’Anton said. ‘Until you came into his life.’

‘Doing all right isn’t enough though, is it?’

‘Isn’t it? I don’t know.’ He looked at the actor to avoid Camille’s eyes. ‘Ah, he’s finished. It’s funny, I could swear – ’

Instead of descending from his chair, the man looked hard and straight at them. ‘I’ll be damned,’ he said. He jumped down, wormed his way across the room, produced some cards from his pocket and thrust them at d’Anton. ‘Have some free tickets,’ he said. ‘How are you, Georges-Jacques?’ He laughed delightedly. ‘You can’t place me, can you? And by hell, you’ve grown!’

‘The prizewinner?’ d’Anton said.

‘The very same. Fabre d’Églantine, your humble servant. Well now, well now!’ He pounded d’Anton’s shoulder, with a stage-effect bunched fist. ‘You took my advice, didn’t you? You’re a lawyer. Either you’re doing quite well, or you’re living beyond your means, or you’re blackmailing your tailor. And you have a married look about you.’

D’Anton was amused. ‘Anything else?’

Fabre dug him in the belly. ‘You’re beginning to run to fat.’

‘Where’ve you been? What have you been up to?’

‘Around, you know. This new troupe I’m with – very successful season last year.’

‘Not here, though, was it? I’d have caught up with you, I’m always at the theatre.’

‘No. Not here. Nimes. All right then. Moderately successful. I’ve given up the landscape gardening. Mainly I’ve been writing plays and touring. And writing songs.’ He broke off and started to whistle something. People turned around and stared. ‘Everybody sings that song,’ he said. ‘I wrote it. Yes, sorry, I am an embarrassment at times. I wrote a lot of those songs that go around in your head, and much good it’s done me. Still, I made it to Paris. I like to come here, to this café I mean, and try out my first drafts. People do you the courtesy of listening, and they’ll give you an honest opinion – you’ve not asked for it, of course, but let that pass. The tickets are for Augusta. It’s at the Italiens. It’s a tragedy, in more ways than one. I think it will probably come off after this week. The critics are after my blood.’

‘I saw Men of Letters,’ Camille said. ‘That was yours, Fabre, wasn’t it?’

Fabre turned. He took out a lorgnette, and examined Camille. ‘The less said about Men of Letters the better. All that stony silence. And then, you know, the hissing.’

‘I suppose you must expect it, if you write a play about critics. But of course, Voltaire’s plays were often hissed. His first nights usually ended in some sort of riot.’

‘True,’ Fabre said. ‘But then Voltaire wasn’t always worried about where his next meal was coming from.’

‘I know your work,’ Camille insisted. ‘You’re a satirist. If you want to get on – well, try toadying to the Court a bit more.’

Fabre lowered his lorgnette. He was immensely, visibly gratified and flattered – just by that one sentence, ‘I know your work.’ He ran his hand through his hair. ‘Sell out? I don’t think so. I do like an easy life, I admit. I try to turn a fast penny. But there are limits.’

D’Anton had found them a table. ‘What is it?’ Fabre said, seating himself. ‘Ten years? More? One says, “Oh, we’ll meet again,” not quite meaning it.’

‘All the right people are drifting together,’ Camille said. ‘You can pick them out, just as if they had crosses on their foreheads. For example, I saw Brissot last week.’ D’Anton did not ask who was Brissot. Camille had a multitude of shady acquaintances. ‘Then, of all people, Hérault just now. I always hated Hérault, but I have this feeling about him now, quite a different feeling. Against my better judgement, but there it is.’

‘Hérault is a Parlementary judge,’ d’Anton told Fabre. ‘He comes from an immensely rich and ancient family. He’s not more than thirty, his looks are impeccable, he’s well-travelled, he’s pursued by all the ladies at Court – ’

‘How sick,’ Fabre muttered.

‘And we’re baffled because he’s just spent ten minutes talking to us. It’s said,’ d’Anton grinned, ‘that he fancies himself as a great orator and spends hours alone talking to himself in front of a mirror. Though how would anyone know, if he’s alone?’

‘Alone except for his servants,’ Camille said. ‘The aristocracy don’t consider their servants to be real people, so they’re quite prepared to indulge all their foibles in front of them.’

‘What is he practising for?’ Fabre asked. ‘For if they call the Estates?’

‘We presume so,’ d’Anton said. ‘He views himself as a leader of reform, perhaps. He has advanced ideas. So he seems to say.’

‘Oh well,’ Camille said. ‘“Their silver and their gold will not be able to deliver them in the day of the wrath of the Lord.” It’s all in the Book of Ezekiel, you see, it’s quite clear if you look at it in the Hebrew. About how the law shall perish from the priests and the council from the ancients. “And the King will mourn, and the Prince shall be clothed with sorrow…” – which I’m quite sure they will be, and quite rapidly too, if they go on as they do at present.’

Someone at the next table said, ‘You ought to keep your voice down. You’ll find the police attending your sermons.’

Fabre slammed his hand down on the table and shot to his feet. His thin face turned brick-red. ‘It isn’t an offence to quote the holy Scriptures,’ he said. ‘In any damn context whatsoever.’ Someone tittered. ‘I don’t know who you are,’ Fabre said vehemently to Camille, ‘but I’m going to get on with you.’

‘Oh God,’ d’Anton muttered. ‘Don’t encourage him.’ It was not possible, considering his size, to get out without being noticed, so he tried to look as if he were not with them. The last thing you need is encouragement, he thought, you make trouble because you can’t do anything else, you like to think of the destruction outside because of the destruction inside you. He turned his head to the door, where outside the city lay. There are a million people, he thought, of whose opinions I know nothing. There were people hasty and rash, people unprincipled, people mechanical, calculating and nice. There were people who interpreted Hebrew and people who could not count, babies turning fish-like in the warmth of the womb and ancient women defying time whose paint congealed and ran after midnight, showing first the wrinkled skin dying and then the yellow and gleaming bone. Nuns in serge. Annette Duplessis enduring Claude. Prisoners at the Bastille, crying to be free. People deformed and people only disfigured, abandoned children sucking the thin milk of duty: crying to be taken in. There were courtiers: there was Hérault, dealing Antoinette a losing hand. There were prostitutes. There were wig-makers and clerks, freed slaves shivering in the squares, the men who took the tolls at the customs posts in the walls of Paris. There were men who had been gravediggers man and boy all their working lives. Whose thoughts ran to an alien current. Of whom nothing was known and nothing could be known. He looked across at Fabre. ‘My greatest work is yet to come,’ Fabre said. He sketched its dimensions in the air. Some confidence trick, d’Anton thought. Fabre was a ready man, wound up like a clockwork toy, and Camille watched him like a child who had been given an unexpected present. The weight of the old world is stifling, and trying to shovel its weight off your life is tiring just to think about. The constant shuttling of opinions is tiring, and the shuffling of papers across desks, the chopping of logic and the trimming of attitudes. There must, somewhere, be a simpler, more violent world.

LUCILE: inaction has its own subtle rewards, but now she thinks it is time to push a little. She had left those nursery days behind, of the china doll with the straw heart. They had dealt with her, Maître Desmoulins and her mother, as effectively as if they had smashed her china skull. Since that day, bodies had more reality – theirs, if not hers. They were solid all right, and substantial. Woundingly, she felt their superiority; and if she could ache, she must be taking on flesh.

Midsummer: Brienne, the Comptroller, borrowed twelve million livres from the municipality of Paris. ‘A drop in the ocean,’ M. Charpentier said. He put the café up for sale; he and Angélique meant to move out to the country. Annette did her duty to the fine weather, making forays to the Luxembourg Gardens. She had often walked there with the girls and Camille; this spring the blossom had smelt faintly sour, as if it had been used before.

Lucile had spent a lot of time writing her journal: working out the plot. That Friday, which began like any other, when my fate was brought up from the kitchen, superscribed to me, and put into my ignorant hand. How that night – Friday to Saturday – I took the letter from its hiding place and put it against the cold ruffled linen of my nightgown, approximately over my shaking heart: the crackling paper, the flickering candlelight, and oh, my poor little emotions. I knew that by September my life would be completely changed.

‘I’ve decided,’ she said. ‘I’m going to marry Maître Desmoulins after all.’ Clinically, she observed how ugly her mother became, when her clear complexion blotched red with anger and fear.

She has to practise for the conflicts the future holds. Her first clash with her father sends her up to her room in tears. The weeks wear on, and her sentiments become more savage: echoed by events in the streets.

THE DEMONSTRATION had started outside the Law Courts. The barristers collected their papers and debated the merits of staying put against those of trying to slip through the crowds. But there had been fatalities: one, perhaps two. They thought it would be safer to stay put until the area was completely cleared. D’Anton swore at his colleagues, and went out to pick his way across the battlefield.

An enormous number of people seemed to be injured. They were what you would call crush injuries, except for the few people who had fought hand-to-hand with the Guards. A respectably dressed man was walking around showing people the hole in his coat where it had been pierced by a bullet. A woman was sitting on the cobblestones saying, ‘Who opened fire, who ordered it, who told them to do it?’ demanding an explanation in a voice sharp with hysteria. Also there were several unexplained knifings.

He found Camille slumped on his knees by a wall scribbling down some sort of testimony. The man who was talking to him was lying on the ground, just his shoulders propped up. All the man’s clothes were in shreds and his face was black. D’Anton could not see where he was injured, but beneath the black his face looked numb, and his eyes were glazed with pain or surprise.

D’Anton said, ‘Camille.’

Camille looked sideways at his shoes, then his eyes travelled upwards. His face was chalk-white. He put down his paper and stopped trying to follow the man’s ramblings. He indicated a man standing a few yards away, his arms folded, his short legs planted apart, his eyes on the ground. Without tone or emphasis, Camille said, ‘See that? That’s Marat.’

D’Anton did not look up. Somebody pointed to Camille and said, ‘The French Guards threw him on the ground and kicked him in the ribs.’

Camille smiled miserably. ‘Must have been in their way, mustn’t I?’

D’Anton tried to get him to his feet. Camille said, ‘No, I can’t do it, leave me alone.’

D’Anton took him home to Gabrielle. He fell asleep on their bed, looking desperately ill.

‘WELL, THERE’S ONE THING,’ Gabrielle said, later that night. ‘If they’d kicked you in the ribs, their boots would have just bounced off.’

‘I told you,’ d’Anton said. ‘I was inside, in an office. Camille was outside, in the riot. I don’t go in for these silly games.’

‘It worries me, though.’

‘It was just a skirmish. Some soldiers panicked. Nobody even knows what it was about.’

Gabrielle was hard to console. She had made plans, settled them, for her house, for her babies, for the big success he was going to enjoy. She feared any kind of turmoil, civil or emotional: feared its stealthy remove from the street to the door to her heart.

When they had friends to dine, her husband spoke familiarly about people in the government, as if he knew them. When he spoke of the future, he would add, ‘if the present scheme of things continues’.

‘You know,’ he said, ‘I think I’ve told you, that I’ve had a lot of work recently from M. Barentin, the President of the Board of Excise. So naturally my work takes me into government offices. And when you’re meeting the people who’re running the country – ’ he shook his head – ‘you start to make judgements about their competence. You can’t help making judgements.’

‘But they’re individuals.’ (Forgive me, she wanted to say, for intruding where I don’t understand.) ‘Is it necessary to question the system itself? Does it follow?’

‘There is really only one question,’ he said. ‘Can it last? The answer’s no. Twelve months from now, it seems to me, our lives will look very different.’

Then he closed his mouth resolutely, because he realized that he had been talking to her about matters that women were not interested in. And he did not want to bore her, or upset her.

PHILIPPE, the Duke of Orléans, is going bald. His friends – or those who wish to be his friends – have obliged him by shaving the hair off their foreheads, so that the Duke’s alopecia appears to be a fad, or whimsy. But no sycophancy can disguise the bald fact.

Duke Philippe is now forty years old. People say he is one of the richest men in Europe. The Orléans line is the junior branch of the royal family, and its princes have rarely seen eye-to-eye with their senior cousins. Duke Philippe cannot agree with King Louis, about anything.

Philippe’s life up to this point had not been auspicious. He had been so badly brought up, so badly turned out, that you might well think it had been done on purpose, to debauch him, to invalidate him, to disable him for any kind of political activity. When he married, and appeared with the new Duchess at the Opéra, the galleries were packed by the public prostitutes decked out in mourning.

Philippe is not a stupid man, but he is a susceptible one, a taker-up of fads and fancies. At this time he has a good deal to complain about. The King interferes all the time in his private life. His letters are opened, and he is followed about by policemen and the King’s spies. They try to ruin his friendship with the dear Prince of Wales, and to stop him visiting England, whence he has imported so many fine women and racehorses. He is continually defamed and calumniated by the Queen’s party, who aim to make him an object of ridicule. His crime is, of course, that he stands too near the throne. He finds it difficult to concentrate for any length of time, and you can’t expect him to read the nation’s destiny in a balance-sheet; but you don’t need to tell Philippe d’Orléans that there is no liberty in France.

Among the many women in his life, one stands out: not the Duchess. Félicité de Genlis had become his mistress in 1772, and to prove the character of his feelings for her the Duke had caused a device to be tattooed on his arm. Félicité is a woman of sweet and iron wilfulness, and she writes books. There are few acres in the field of human knowledge that she has not ploughed with her harrowing pedantry. Impressed, astounded, enslaved, the Duke has placed her in charge of his children’s education. They have a daughter of their own, Pamela, a beautiful and talented child whom they pretend is an orphan.

From the Duke, as from his children, Félicité exacts respect, obedience, adoration: from the Duchess, a timid acquiescence to her status and her powers. Félicité has a husband, of course – Charles-Alexis Brulard de Sillery, Comte de Genlis, a handsome ex-naval officer with a brilliant service record. He is close to Philippe – one of his small, well-drilled army of fixers, organizers, hangers-on. People had once called their marriage a love-match; twenty-five years on, Charles-Alexis retains his good looks and his polish, and indulges daily and nightly his ruling passion – gambling.

Félicité has even reformed the Duke – moderated some of his wilder excesses, steered his money and his energy into worthwhile channels. Now in her well-preserved forties, she is a tall, slender woman with dark-blonde hair, arresting brown eyes, and a decisive aspect to her features. Her physical intimacy with the Duke has ceased, but now she chooses his mistresses for him and directs them how to behave. She is accustomed to be at the centre of things, to be consulted, to dispense advice. She has no love for the King’s wife, Antoinette.

The consuming frivolity of the Court has left a kind of hiatus, a want of a cultural centre for the nation. It is arranged by Félicité that Philippe and his court shall supply that lack. It is not that she has political ambitions for him – but it happens that so many intellectuals, so many artists and scholars, so many of the people one wishes to cultivate, are liberal-minded men, enlightened men, men who look forward to a new dispensation; and doesn’t the Duke have every sympathy? In this year, 1787, there are gathered about him a number of young men, aristocrats for the most part, all of them ambitious and all of them with a vague feeling that their ambitions have somehow been thwarted, that their lives have somehow become unsatisfactory. It is arranged that the Duke, who feels this more keenly than most, shall be a leader to them.

The Duke wishes to be a man of the people, especially of the people of Paris; he wishes to be in touch with their moods and concerns. He keeps court in the heart of the city, at the Palais-Royal. He has turned the gardens over to the public and leased out the buildings as shops and brothels and coffee houses and casinos: so that at the epicentre of the nation’s fornication, rumourmongering, pickpocketing and street-fighti g, there sits Philippe: Good Duke Philippe, the Father of His People. Only nobody shouts that; it has not been arranged yet.

Summer of ’87, Philippe is fitted out and launched for trial manoeuvres. In November the King decides to meet the obstructive Parlement in a Royal Session, to obtain registration of edicts sanctioning the raising of a loan for the state. If he cannot get his way, he will be forced to call the Estates-General. Philippe prepares to confront the royal authority – as de Sillery would have said – broadside on.

CAMILLE saw Lucile briefly outside Saint-Sulpice, where she had been attending Benediction. ‘Our carriage is just over there,’ she said. ‘Our man, Théodore, is generally on my side, but he will have to bring it across in a minute. So let’s make this quick.’

‘Your mother’s not in it, is she?’ He looked alarmed.

‘No, she’s skulking at home. By the way, I heard you were in a riot.’

‘How did you hear that?’

‘There’s this grapevine. Claude knows this man called Charpentier, yes? Well, you can imagine, Claude’s thrilled.’

‘You shouldn’t stand here,’ he said. ‘Awful day. You’re getting wet.’

She had the distinct impression that he would like to bundle her into the carriage, and have done with her. ‘Sometimes I dream,’ she said, ‘of living in a warm place. One where the sun shines every day. Italy would be nice. Then I think, no, stay at home and shiver a little. All this money that my father has set aside for my dowry, I don’t think I should let it slip through my fingers. It would be downright ungrateful to run away from it. We ought to be married here,’ she waved a hand, ‘at a time of our own choosing. We could go to Italy afterwards, for a holiday. We’ll need a holiday after we’ve fought them and won. We could retain some elephants, and go across the Alps.’

‘So you do mean to marry me then?’

‘Oh yes.’ She looked at him, astonished. How could it be that she had forgotten to let him know? When it was all she had been thinking about, for weeks? Perhaps she’d thought the grapevine would do that, too. But the fact that it hadn’t…Could it be that he had put it to the back of his mind in some way? ‘Camille…’ she said.

‘Very well,’ he said. ‘But if I’m to go bespeaking elephants, I can’t just do it on a promise. You’ll have to swear me a solemn oath. Say “By the bones of the Abbé Terray.”’

She giggled. ‘We’ve always taken the Abbé Terray very seriously.’

‘That’s what I mean, a serious oath.’

‘As you like. By the bones of the Abbé Terray, I swear I will marry you, whatever happens, whatever anyone says, and even if the sky falls in. I feel we should kiss but,’ she extended her hand, ‘this is the most I can manage. Otherwise Théodore will get a crisis of conscience, and come over right away.’

‘You might take your glove off,’ he said. ‘It would be a start.’

She took her glove off, and gave him her hand. She thought he might kiss her fingertips, but in fact he took those fingertips, turned her hand over rather forcefully, and held her palm for a second against his mouth. And just that; he didn’t kiss it; just held it there, still. She shivered. ‘You know a thing or two, don’t you?’ she said.

By now, her carriage had arrived. The horses breathed patiently, shifted their feet; Théodore positioned his back to them, and scanned the street with deep interest. ‘Now, listen,’ she said. ‘We come here because my mother has a tendresse for one of the clergy. She thinks him spiritually fine, elevated.’

Théodore turned now. He opened the door for her. She turned her back. ‘His name is Abbé Laudréville. He visits us as often as my mother needs to discuss her soul, which these days is at least three times a week. And he thinks my father a man of no sensibility at all. So write.’ The door slammed, and she spoke to him from the window. ‘I imagine you have a way with elderly priests. You write the letters and he’ll bring them. Come to evening Mass, and you’ll get replies.’ Théodore gathered the reins. She bobbed her head in. ‘Piety to some purpose,’ she muttered.

NOVEMBER: Camille at the Café du Foy, unable to get his words out fast enough. ‘My cousin de Viefville actually spoke to me in public, he was so anxious to tell someone what had happened. So: the King came in and slumped there half-asleep, as usual. The Keeper of the Seals spoke, and said that the Estates would be convoked, but not till ’92, which is a lifetime away – ’

‘I blame the Queen.’

‘Shh.’

‘And this led to some protest, and then there was discussion of the edicts that the King wants them to register. As they were approaching the vote, the Keeper of the Seals went up to the King and spoke to him privately, and the King just cut the discussion short, and said the edicts were to be registered. Just ordered it to be done.’

‘But how can he – ’

‘Shh.’

Camille looked around at his audience. He was aware that a singular event had occurred once again: his stutter had vanished. ‘Then Orléans got up, and everyone turned around and stared, and he was absolutely white, de Viefville said. And the Duke said, “You can’t do that. It’s illegal.” Then the King became flustered, and he shouted out “It is legal, because I wish it.”’

Camille stopped. There was an immediate buzz – of protest, of simulated horror, of speculation. At once he felt that hideous urge to destroy his own case; he was enough of a lawyer, perhaps, or perhaps, he wondered, am I just too honest? ‘Listen, everyone, please – this is what de Viefville says the King said. But I’m not sure if one can believe it – isn’t it too pat? I mean, if people wanted to engineer a constitutional crisis, isn’t that just what they’d hope for him to say? Actually, perhaps – because he’s not a bad man, is he, the King…I think he probably didn’t say that at all, he probably made some feeble joke.’

D’Anton noted this: that Camille did not stutter, and that he talked to every person in the crowded room as if he were speaking only to them. But someone said, ‘Well, get on, then!’

‘The edicts were registered. The King left. As soon as he was outside the door, the edicts were annulled and struck off the books. Two members of the Parlement are arrested on lettres de cachet. The Duke of Orléans is exiled to his estates at Villers-Cotterêts. Oh – and I am invited to dine with my esteemed cousin de Viefville.’

AUTUMN PASSED. It’s like, Annette said, if the roof fell in, you would scrabble in the debris for what valuables were left; you wouldn’t sit down among the falling masonry saying ‘why, oh why?’ The prospect of Camille, of what he was going to do to herself and her daughter, seemed too ghastly to resist. She accepted it as people become reconciled to the long course of a terminal illness; at times, she desired death.