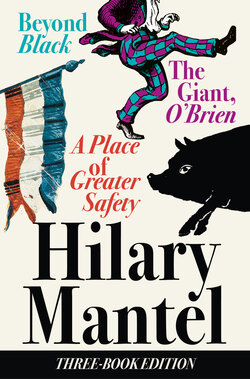

Читать книгу Three-Book Edition - Hilary Mantel - Страница 26

I. Virgins (1789)

ОглавлениеMONSIEUR SOULÈS, Elector of Paris, was alone on the walls of the Bastille. They had come for him early in the evening and said, Lafayette wants you. De Launay’s been murdered, they said, so you’re governor pro tem. Oh no, he said, why me?

Pull yourself together, man, they’d said; there won’t be any more trouble.

Three a.m. on the walls. He had sent back his weary escort. The night’s black as a graceless soul: the body yearning towards extinction. From Saint-Antoine, lying below him, a dog howled painfully at the stars. Far to his left a torch licked feebly at the blackness, burning in a wall-bracket: lighting the clammy stones, the weeping ghosts.

Jesus, Mary and Joseph, help us now and in the hour of our deaths.

He was looking into a man’s chest, and the man had a musket.

There should be, he thought wildly, a challenge, you are supposed to say, who goes there, friend or foe? What if they say ‘foe’, and keep coming?

‘Who are you?’ the chest said.

‘I am the governor.’

‘The governor is dead and all chopped up into little pieces.’

‘So I’ve heard. I am the new governor. Lafayette sent me.’

‘Oh really? Lafayette sent him,’ the chest said. There were sniggers from the darkness. ‘Let’s see your commission.’

Soulès reached inside his coat: handed over the piece of paper that he had kept next to his heart all these nervous hours.

‘How do you expect me to read it in this light?’ He heard the sound of paper crumpling. ‘Right,’ the chest said with condescension. ‘I am Captain d’Anton, of the Cordeliers Battalion of the citizens’ militia, and I am arresting you because you seem to me a very suspicious character. Citizens, carry out your duty.’

Soulès opened his mouth.

‘No point shouting. I have inspected the guard. They’re drunk and sleeping like the dead. We’re taking you to our district headquarters.’

Soulès peered into the darkness. There were at least four armed men behind Captain d’Anton, perhaps more in the shadows.

‘Please don’t think of resisting.’

The captain had a cultured and precise voice. Small consolation. Keep your head, Soulès told himself grimly.

THEY RANG THE TOCSIN at Saint-André-des-Arts. A hundred people were on the streets within minutes. A lively district, as d’Anton had always said.

‘Can’t be too careful,’ Fabre said. ‘Perhaps we should shoot him.’

Soulès said, over and over again, ‘I demand to be taken to City Hall.’

‘Demand nothing,’ d’Anton said. Then a thought seemed to strike him. ‘All right. City Hall.’

It was an eventful journey. They had to take an open carriage, as there was nothing else available. There were people already (or still) in the streets, and it was obvious to them that the Cordeliers citizens needed help. They ran along the side of the carriage and shouted, ‘Hang him.’

When they arrived, d’Anton said, ‘It’s much as I thought. The government of the city is in the hands of anyone who turns up and says, “I’m in charge.”’ For some weeks now, an unofficial body of Electors had been calling itself the Commune, the city government; M. Bailly of the National Assembly, who had presided over the Paris elections, was its organizing spirit. True, there had been a Provost of Paris till yesterday, a royal appointee; but the mobs had murdered him, when they had finished with de Launay. Who runs the city now? Who has the seals, the stamps? This is a question for the daylight hours. The Marquis de Lafayette, an official said, had gone home to bed.

‘A fine time to be asleep. Get him down here. What are we to think? A patrol of citizens leaves their beds to inspect the Bastille, wrested from tyrants at enormous cost – they find the guard the worse for drink, and this person, who cannot explain himself, claiming to be in charge.’ He turned to his patrol. ‘Someone should account to the people. There are skeletons to be counted, one would think. Why, there may be helpless victims chained in dungeons still.’

‘Oh, they’re all accounted for,’ the official said. ‘There were only seven people in there, you know.’

Nevertheless, d’Anton thought, the accommodation was always available. ‘What about the prisoners’ effects?’ he asked. ‘I myself have heard of a billiard table that went in twenty years ago and has never come out.’

Laughter from the men behind. A blank wild stare from the official. D’Anton’s mood was suddenly sober. ‘Get Lafayette,’ he said.

Jules Paré, released from clerking, grinned into the darkness. Lights flared in the Place de Grève. M. Soulès eyes were drawn irresistibly to the Lanterne – a great iron bracket from which a light swung. At that spot, not many hours earlier, the severed head of the Marquis de Launay had been kicked around like a football among the crowd. ‘Pray, M. Soulès,’ d’Anton suggested pleasantly.

DAWN HAD BROKEN when Lafayette appeared. D’Anton saw with disappointment that his turn-out was immaculate; but his newly shaven face was flushed along the cheek bones.

‘Do you know what time it is?’

‘Five o’clock?’ d’Anton said helpfully. ‘Just guessing. I always thought that soldiers were ready to get up at any time of the night.’

Lafayette turned away for a second. He clenched his fists, and cast up his eyes to the red-fingered sky. When he turned back his voice was crisp and amiable. ‘Sorry. That was no way to greet you. Captain d’Anton, isn’t it? Of the Cordeliers?’

‘And a great admirer of yours, General,’ d’Anton said.

‘How kind.’ Lafayette gazed wonderingly at the subordinate this new world had brought him: this towering, broad-shouldered, scarfaced man. ‘I don’t know that this was necessary,’ he said, ‘but I suppose you’re only doing your – best.’

‘We’ll try to make our best good enough,’ Captain d’Anton said doggedly.

For an instant, a suspicion crossed the general’s mind: was it possible that he was the victim of a practical joke? ‘This is M. Soulès. I formally identify him. M. Soulès has my full authority. Yes, of course I’ll give him a new piece of paper. Will that do?’

‘That will do fine,’ the captain said promptly. ‘But your word alone will do for me, any time, General.’

‘I’ll get back home now, Captain d’Anton. If you’ve quite finished with me.’

The captain didn’t understand sarcasm. ‘Sleep well,’ he said. Lafayette turned smartly, thinking, we really must decide if we’re going to salute.

D’Anton wheeled his patrol back to the river, his eyes glinting. Gabrielle was waiting for him at home. ‘Why ever did you do it?’

‘Shows initiative, doesn’t it?’

‘You’ve only annoyed Lafayette.’

‘That’s what I mean.’

‘It’s just the sort of game people around here like,’ Paré said. ‘I should think they really will make you a captain in the militia, d’Anton. Also, I should think they’ll elect you president of the district. Everybody knows you, after all.’

‘Lafayette knows me,’ d’Anton said.

WORD FROM VERSAILLES: M. Necker is recalled. M. Bailly is named Mayor of Paris. Momoro the printer works through the night setting up the type for Camille’s pamphlet. Contractors are brought in to demolish the Bastille. People take it away, stone by stone, for souvenirs.

The Emigration begins. The Prince de Condé leaves the country in haste, lawyers’ bills and much else unpaid. The King’s brother Artois goes; so do the Polignacs, the Queen’s favourites.

On 17 July, Mayor Bailly leaves Versailles in a flower-bedecked coach, arrives at City Hall at ten a.m., and immediately sets off back again, amid a crowd of dignitaries, to meet the King. They get as far as the Chaillot fire-pump: mayor, Electors, guards, city keys in silver bowl – and there they meet three hundred deputies and the royal procession, coming the other way.

‘Sire,’ says Mayor Bailly, ‘I bring Your Majesty the keys of your good city of Paris. They are the very ones that were presented to Henri IV; he had reconquered his people, and here the people have reconquered their King.’

It sounds tactless, but he means it kindly. There is spontaneous applause. Militiamen three deep line the route. The Marquis de Lafayette walks in front of the King’s coach. Cannon are fired in salute. His Majesty steps down from the coach and accepts from Mayor Bailly the nation’s new tricolour cockade: the monarchy’s white has been added to the red and the blue. He fastens the cockade to his hat, and the crowd begins to cheer. (He had made his will before he left Versailles.) He walks up the staircase of City Hall under an arch of swords. The delirious crowd pushes around him, jostling him and trying to touch him to see if he feels the same as other people. ‘Long live the King,’ they shout. (The Queen had not expected to see him again.)

‘Let them be,’ he says to the soldiers. ‘I believe they are truly fond of me.’

Some semblance of normal life takes hold. The shops re-open. An old man, shrunken and bony, with a long white beard, is paraded through the city to wave to the crowds who still hang about on every street. His name is Major Whyte – he is perhaps an Englishman, perhaps an Irishman – and no one knows how long he has been locked up in the Bastille. He seems to enjoy the attention he is getting, though when asked about the circumstances of his incarceration he weeps. On a bad day he does not know who he is at all. On a good day he answers to Julius Caesar.

EXAMINATION of Desnot, July 1789, in Paris:

Being asked if it was with this knife that he had mutilated the head of the Sieur de Launay, he answered that it was with a black knife, a smaller one; and when it was observed to him that it was impossible to cut off heads with so small and weak an instrument, he answered that, in his capacity as cook, he had learned how to handle meat.

18 August 1789

At Astley’s Amphitheatre, Westminster Bridge

(after rope-dancing by Signior Spinacuta)

An Entire New and Splendid Spectacle

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

From Sunday 12 July to Wednesday 15 July (inclusive)

called

PARIS IN AN UPROAR

displaying one of the grandest and most extraordinary

entertainments that ever appeared

grounded on

Authentic Fact

BOX 3s., PIT 2s., GAL 1s., SIDE GAL 6d.

The doors to be opened at half-past five, to begin at

half-past six o’clock precisely.

CAMILLE WAS NOW persona non grata at the rue Condé. He had to rely on Stanislas Fréron to come and go, bring him the news, convey his sentiments (and letters) to Lucile.

‘You see,’ Fréron told him, ‘if I grasp the situation, she loved you for your fine spiritual qualities. Because you were so sensitive, so elevated. Because – as she believed – you were on a different planet from us more coarse-grained mortals. But now what happens? You turn out to be the kind of man who goes storming round the streets covered in mud and blood, inciting butchery.’

D’Anton said that Fréron was ‘trying to clear the field for himself, one way or another’. His tone was cynical. He quoted the remark Voltaire had made about Rabbit’s father: ‘If a snake bit Fréron, the snake would die.’

The truth was – but Fréron was not about to mention this – Lucile was more besotted than ever. Claude Duplessis remained convinced that if he could introduce his daughter to the right man she’d get over her obsession. But he’d have a hard job finding anyone who remotely interested her; if he found them suitable, it followed she wouldn’t. Everything about Camille excited her: his unrespectability, his faux-naïf little mannerisms, his skittish intellect. Above all, the fact that he’d suddenly become famous.

Fréron – the old family friend – had seen the change in Lucile. A pretty curds-and-whey miss had become a dashing young woman, with a mouth full of political jargon and a knowing light in her eye. Be good in bed, Fréron thought, when she gets there. He himself had a wife, a stay-at-home who hardly counted in his scheme of things. Anything’s possible, these days, he thought.

Unfortunately, Lucile had taken up this ludicrous fashion for calling him ‘Rabbit’.

CAMILLE didn’t sleep much: no time. When he did, his dreams exhausted him. He dreamt, inter alia, that the whole world had gone to a party. The scene, variously, was the Place de Grève: Annette’s drawing room: the Hall of the Lesser Pleasures. Everyone in the world was at this party. Angélique Charpentier was talking to Hérault de Séchelles; they were comparing notes about him, exploding his fictions. Sophie from Guise, whom he had slept with when he was sixteen, was telling everything to Laclos; Laclos had his notebook out, and Maître Perrin was at his elbow, demanding attention in a lawyer’s bellow. The smirking, adhesive Deputy Pétion had linked arms with the dead governor of the Bastille; de Launay flopped about, useless without his head. His old schoolfriend, Louis Suleau, was arguing in the street with Anne Théroigne. Fabre and Robespierre were playing a children’s game; they froze like statues when the argument stopped.

He would have worried about these dreams, except that he was going out to dinner every night. He knew they contained a truth; all the people in his life were coming together now. He said to d’Anton, ‘What do you think of Robespierre?’

‘Max? Splendid little chap.’

‘Oh no, you mustn’t say that. He’s sensitive about his height. He used to be, anyway, when we were at school.’

‘Good God,’ d’Anton said. ‘Then just take it that he’s splendid. I haven’t time to pussyfoot around people’s vanities.’

‘And you accuse me of having no tact.’

‘Are you trying to start an argument?’

So he never found out what d’Anton thought of Robespierre.

He said to Robespierre, ‘What do you think of d’Anton?’ Robespierre took off his spectacles and polished them. He mulled over the question. ‘Very pleasant,’ he said at length.

‘But what do you think, really? You’re being evasive. I mean you don’t just think that someone is pleasant, and that’s all you think, surely?’

‘Oh, you do, Camille, you do,’ Robespierre said gently.

So he never found out what Robespierre thought of d’Anton, either.

THE EX-MINISTER FOULON had once remarked, in a time of famine, that if the people were hungry they could eat grass. Or so it was believed. That was why – and reason enough – on 22 July he was in the Place de Grève, with an audience.

He was under guard, but it seemed likely that the small but ugly crowd, who had plans for him, would tear him away. Lafayette arrived and spoke to them. He had no wish to stand in the way of the people’s justice; but at least Foulon should have a fair trial.

‘What’s the use of a trial,’ someone called out, ‘for a man who’s been convicted these thirty years?’

Foulon was old; it was many years since he had ventured his bon mot. To escape this fate he had hidden, and put about rumours of his own death. It was said that a funeral had been conducted over a coffin packed with stones. Tracked down, arrested, he now looked beseechingly at the general. From the narrow streets beyond City Hall, there came the low rumble which Paris now identified as marching feet.

‘They’re converging,’ an aide reported to the general. ‘From the Palais-Royal on one hand, and from Saint-Antoine on the other.’

‘I know,’ the general said. ‘I can hear on both sides of my head. How many?’

No one could estimate. Too many. He looked at Foulon without much sympathy. He had no forces on hand; if the city authorities wanted to protect Foulon, they would have to do it themselves. He glanced at his aide, gave a minute shrug.

They pelted Foulon with grass, tied a bunch of it on his back, stuffed his mouth with it. ‘Eat up the nice grass,’ they urged him. Gagging on the sharp stalks, he was dragged across the Place de Grève, where a rope was tossed over the iron projection of the Lanterne. For a few moments the old man swung where at dusk the great light would swing. Then the rope snapped; he plummeted into the crowd. Mauled and kicked, he was hoisted back into the air. Again the rope broke. The mob’s hands grasped him, careful not to deliver the coup de grace. A third noose was placed about the livid neck. This time the rope held. When he was dead, or nearly so, the mob cut off his head and speared it on a pike.

At the same time, Foulon’s son-in-law Berthier, the Intendant of Paris, had been arrested in Compiègne and conveyed, glassy-eyed with terror, to City Hall. He was bundled inside, through a crowd that peppered him with crusts of sour black bread. Shortly afterwards he was bundled out again, on his way to the Abbaye prison; shortly after that, he was bundled to his death – strangled perhaps, or finished with a musket-ball, for who knew the moment? And perhaps he was not dead either when a sword began to hack at his neck. His head in turn was stabbed on to a pike. The two processions met and the pikes swayed together, bringing the severed heads nose-to-nose. ‘Kiss Daddy!’ the mob called out. Berthier’s chest was sawn open, and the heart was wrenched out. It was skewered on to a sword, marched to City Hall, and flung down on Bailly’s desk. The mayor almost collapsed. The heart was then taken to the Palais-Royal. Blood was squeezed out of it into a glass, and people drank it. They sang:

A party isn’t a party

When the heart’s not in it.

THE NEWS OF THE LYNCHINGS at Paris caused consternation at Versailles, where the Assembly was absorbed in a debate on human rights. There was shock, outrage, protest: where was the militia while this was going on? It was generally believed that Foulon and his son-in-law had been speculators in grain, but the deputies, moving between the Hall of the Lesser Pleasures and the well-stocked larders of their lodgings, had lost touch with what is often called popular sentiment. Disgusted at their hypocrisy, Deputy Barnave asked them, ‘This blood that has been shed, was it so pure?’ Revolted, they shouted him down, marking him in their minds as dangerous. The debate would resume; they were intent on framing a ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’. Some were heard to mutter that the Assembly should write the constitution first, since rights exist in virtue of laws; but jurisprudence is such a dull subject, and liberty so exciting.

Night of 4 August, the feudal system ceases to exist in France. The Vicomte de Noailles rises and, voice shaking with emotion, gives away all he possesses – not a great deal, as his nickname is ‘Lackland’. The National Assembly surges to its feet for a saturnalia of magnanimity; they slough off serfs, game laws, tithes in kind, seigneural courts – and tears of joy stream down their faces. A member passes a note to the President – ‘Close the session, they have lost control of themselves.’ But the hand of heaven can’t hold them back – they vie in the pandemonium to be each more patriotic than the last, they gabble to relinquish what belongs to them and with eagerness even greater what belongs to others. Next week, of course, they will try to backtrack; but it will be too late.

And Camille moves around Versailles spreading a scatter of crumpled paper, generating in the close silence of the summer nights the prose he no longer despises…

It is on that night, more so than on Holy Saturday, that we came forth from the wretched bondage of Egypt…That night restored to Frenchmen the rights of man, and declared all citizens equal, equally admissable to all offices, places and public employ; again, that night has snatched all civil offices, ecclesiastical and military from wealth, birth and royalty, to give them to the nation as a whole on the basis of merit. That night has taken from Mme d’Epr— her pension of 20,000 livres for having slept with a minister…Trade with the Indies is now open to everyone. He who wishes may open a shop. The master tailor, the master shoemaker, the master wig-maker will weep, but the journeymen will rejoice, and there will be lights in the attic windows…O night disastrous for the Grand Chamber, the clerks, the bailiffs, the lawyers, the valets, for the secretaries, for the under-secretaries, for all plunderers…But O wonderful night, vera beata nox, happy for everyone, since the barriers that excluded so many from honour and employment have been hurled down for ever, and today there no longer exist among the French any distinctions but those of virtue and talent.

A DARK CORNER, in a dark bar: Dr Marat hunched over a table. August 4 was a sick joke, he said.

He scowled at the manuscript in front of him. ‘Vera beata nox – I wish it were true, Camille. But you’re myth-making, do you see? You’re making a legend of what is happening, a legend of the Revolution. You want to have artistry, you see, where there’s only the necessity – ’ He broke off. His small body seemed to contract in pain.

‘Are you ill?’

‘Are you?’

‘No, I’ve just been drinking too much.’

‘With your new friends, I suppose.’ Marat shuffled back on the bench, the same expression of tension and discomfort on his face; then he considered Camille, his fingers tapping arhythmically on the table top. ‘Feeling safe, are we?’

‘Not especially. I’ve been warned I might be arrested.’

‘Don’t expect the Court to stand on formalities. A man with a knife could do a nice job on you. Or on me for that matter. What I’m going to do is move into the Cordeliers district. Somewhere I can shout for help. Why don’t you move in there too?’ Marat grinned, showing his dreadful teeth. ‘All neighbours together. Very cosy.’ He bent his head over the papers, scrabbling through them, stabbing with his forefinger. ‘What you say next, I approve. It would have taken the people years of civil war, at any other time, to rid themselves of such enemies as Foulon. And in wars, thousands of people die, don’t they? Therefore the lynchings are quite acceptable. They are the humane alternative. You may be made to suffer for that sentiment, but don’t be afraid to take it to the printer.’ Thoughtfully the doctor rubbed the bridge of his flat nose: so prosaic, the gesture, the tone. ‘You see what we must do, Camille, is to cut off heads. The longer we delay, the more we will have to decapitate. Write that. The necessity is to kill people, and to cut off their heads.’

FIRST TENTATIVE SCRAPE of the bow on gut. One, two: d’Anton’s fingers tapped the pommel of his sabre. His neighbours stamped and shrilled under his window, flourishing seating plans. The orchestra of the Royal Academy of Music was tuning up. Good idea of his, hiring them, gives the occasion a bit of tone. There’d also, of course, be a military band. As president of the district and a captain in the National Guard (as the citizens’ militia now called itself) he was responsible for all parts of the day’s arrangements.

‘You’re fine,’ he said to his wife, not looking at her. He was sweating inside his new uniform: white breeches, black top-boots, blue tunic faced with white, scarlet collar proving too tight. Outside, the sun blistered paint.

‘I asked Camille’s friend Robespierre to come over for the day,’ he said. ‘But he can’t take time off from the Assembly. Very conscientious.’

‘That poor boy,’ Angélique said. ‘I can’t think what kind of a family he comes from. I said to him, my dear, aren’t you homesick? Don’t you miss your own people? He said – serious as may be – “Well, Mme Charpentier, I miss my dog.”’

‘I rather liked him,’ Charpentier said. ‘How he ever got mixed up with Camille I can’t imagine. Now,’ he rubbed his hands, ‘what’s the order of the day?’

‘Lafayette will be here in fifteen minutes. We all go to Mass, the priest blesses our new battalion flag, we file out, run it up, march past, Lafayette stands about looking like a commander-in-chief. I assume he will expect to be cheered. I should think there’ll be enough oafs to make a respectable din, even in this cynical district.’

‘I’m still not sure I understand.’ Gabrielle sounded aggrieved. ‘Is the militia on the King’s side?’

‘Oh, everybody is on the King’s side,’ her husband said. ‘It’s just his ministers and his servants and his brothers and his wife we can’t stand. Louis is all right, silly old duffer.’

‘But why do people say that Lafayette’s a republican?’

‘In America he’s a republican.’

‘Are there any republicans here?’

‘Very few.’

‘Would they kill the King?’

‘Heavens, no. We leave that sort of thing to the English.’

‘Would they keep him in prison?’

‘I don’t know. Ask Mme Robert when you see her. She’s one of the extremists. Or Camille.’

‘So if the National Guard is on the King’s side -’

‘On the King’s side,’ he interrupted her, ‘as long as he doesn’t try to go back to where we were before July.’

‘Yes, I understand that. It’s on the King’s side, and against republicans. But Camille and Louise and François are republicans, aren’t they? So if Lafayette told you to arrest them, would you do it?’

‘Good God, no. I’m not going to do his dirty work.’

And he thought, we could be a law unto ourselves in this district. I might not be the battalion commander, but he’s under my thumb.

Camille arrived, breathless and ebullient. ‘The news couldn’t be better,’ he said. ‘In Toulouse my new pamphlet has been burned by the public executioner. It’s too kind of them, the publicity will certainly mean a second edition. And in Oléron a bookshop that was selling it has been attacked by monks, and they threw out all the stock and started a fire and carved up the bookseller.’

‘I don’t think that’s very funny,’ Gabrielle said.

‘No. Quite tragic really.’

A pottery outside Paris was turning out his picture on thick glazed crockery in a strident yellow and blue. This is what happens when you become a public figure; people eat their dinners off you.

There was not a breath of wind when they ran up the new flag; it lay around its pole like a lolling tricolour tongue. Gabrielle stood between her father and mother. Her neighbours the Gélys were on her left, little Louise wearing a new hat of which she was insufferably proud. She was conscious of people’s eyes upon her: there, they were saying, that’s d’Anton’s wife. She heard someone say, ‘How handsome she is, have they children?’ She looked up at her husband, who stood on the church steps, his prize-fighter bulk towering over the ramrod figure of Lafayette. She worked up some contempt for the general, because of her husband’s contempt. She could see that they were being polite to each other. The commander of the battalion waved his hat in the air, raised the shout for Lafayette. The crowd cheered; the general acknowledged them with a spare smile. She half closed her eyes against the sun. Behind her she could hear Camille’s voice running on, talking to Louise Robert exactly as if she were a man. The deputies from Brittany, he was saying, and the initiative in the Assembly. I wanted to go to Versailles as soon as the Bastille was taken – she heard Mme Robert’s muffled agreement – but it should be done as soon as possible. He’s talking about another riot, she thought: another Bastille. Then from behind her, there was a shout: ‘Vive d’Anton.’

She turned, amazed and gratified. The cry was taken up. ‘It’s only a few Cordeliers,’ Camille said, apologetically. ‘But soon it will be the whole city.’

A few minutes later, the ceremony was over and the party could begin. Georges was down among the crowd, hugging her. ‘I was thinking,’ Camille said. ‘It’s time you took out that apostrophe from your name. It doesn’t suit the times.’

‘You may be right,’ her husband said. ‘I’ll do it gradually – no point making an announcement.’

‘No, do it suddenly,’ Camille said. ‘So that everyone knows where you stand.’

‘Bully,’ Georges-Jacques said fondly. He was acquiring it too: this appetite for confrontation. ‘Do you mind?’ he asked her.

‘I want you to do whatever you think best,’ she said. ‘I mean, whatever you think right.’

‘Suppose they did not coincide?’ Camille asked her. ‘I mean, what he thought best and what he thought right?’

‘But they would,’ she said, flustered. ‘Because he is a good man.’

‘That is profound. He will suspect you of thinking while he is not in the house.’

Camille had spent the previous day at Versailles, and in the evening had gone with Robespierre to a meeting of the Breton Club. It was the forum now for the liberal deputies, those inclined to the popular cause and suspicious of the Court. Some of the nobles attended; the frenzied Fourth of August had been calculated quite carefully there. Men who were not deputies were welcomed, if their patriotism was well known.

And whose patriotism was better known than his? Robespierre urged him to speak. But he was nervous, had difficulty making himself heard. The stutter was bad. The audience were not patient with him. He was just a mob-orator, an anarchist, as far as they could see. All in all it was a miserable, deflating occasion. Robespierre sat looking at his shoe-buckles. When Camille came down from the rostrum to sit beside him, he didn’t look up; just flicked his green eyes sideways, and smiled his patient, meditative smile. No wonder he had no encouragement to offer. Whenever he stood up in the Assembly, unruly members of the nobility would pretend to blow candles out, with a great huffing and puffing; or a few of them would get together and orchestrate their imitation of a rabid lamb. No point him saying, ‘You were fine, Camille.’ No point in comforting lies.

After the meeting was closed, Mirabeau took the rostrum, and performed for his well-wishers and sycophants an imitation of Mayor Bailly trying to decide whether it was Monday or Tuesday: of Mayor Bailly viewing the moons of Jupiter to find the answer, and finally admitting (with an obscene flourish) that his telescope was too small. Camille was not much entertained by this; he felt almost tearful. Finishing to applause, the Comte strode down from the rostrum, slapped a few backs, and wrung a few hands. Robespierre touched Camille’s elbow: ‘Let’s get off, shall we?’ he suggested.

Too late. The Comte spied Camille. He caught him up in a rib-cracking hug. ‘You were grand,’ he said. ‘Ignore these provincials. Leave them to their poxy little standards. None of them could have done what you did. None of them. The fact is, you terrify them.’

Robespierre had faded to the back of the meeting room, trying to get out of the way. Camille looked so cheered up, so delighted at the prospect of terrifying people. Why couldn’t he have said what Mirabeau had said? It was all perfectly true. And he wanted to make things right for Camille, he wanted to look after him. Nearly twenty years ago he’d promised to look after him, and he saw nothing to suggest he’d been relieved of the duty. But there it was – he didn’t have the gift of saying the right thing. Camille’s needs and wishes were a closed book, largely: a volume written in a language he’d never learned. ‘Come to supper,’ he heard the Comte say. ‘And let’s tow the lamb along, why don’t we? Give him some red meat to fall on.’

There were fourteen at table. Tender beef bled on to the plates. Turbot’s slashed flesh breathed the scent of bay leaves and thyme. Blue-black shells of aubergines, seared on top, yielded creamy flesh to the probing knife.

The Comte was living very well these days. It was hard to tell if he was just running up more debts or if he could suddenly afford it; if the latter, one wondered how. He had a secret correspondence with a variety of sources. His public utterances had an air both sonorous and cryptic, and he had bought a diamond on credit for his mistress, the publisher’s wife. And how pleasant he was, that evening, to young Robespierre. Why? Politeness costs nothing, he thought. But over these last weeks he had been watching the deputy, noting the frequent dryness of his tone, noting his (apparent) indifference to other people’s opinion of him, noting the flicker of ideas through the lawyer’s brain that is no doubt, he thought, sufficient unto the day.

All that evening he talked to the Candle of Arras, in a low confidential tone. When you get down to it, he thought, there’s not much difference between politics and sex; it’s all about power. He didn’t suppose he was the first person in the world to make this observation. It’s a question of seduction, and how fast and cheap you can effect it: if Camille, he thought, approximates to one of those little milliners who can’t make ends meet – in other words, an absolute pushover – then Robespierre is a Carmelite, mind set on becoming Mother Superior. You can’t corrupt her; you can wave your cock under her nose, and she’s neither shocked nor interested: why should she be, when she hasn’t the remotest idea what it’s for?

They talked about the King, and whether he should have a veto on the legislation passed by the Assembly. Robespierre thought no. Mirabeau thought yes – or thought he could think yes, if the price were right. They talked about how these things were managed in England; Robespierre corrected his facts in a hurried, half-amused way. He accepted the correction, softened him up; when he was rewarded by a precise triangular smile, he felt a most extraordinary flood of relief.

Eleven o’clock: the rabid lamb excused himself, slipped out of the room. It’s something to know he’s mortal, that he has to piss like other men. Mirabeau felt strange, unwontedly sober, unwontedly cold. He looked across the table at one of his Genevans. ‘That young man will go far,’ he said. ‘He believes everything he says.’

Brulard de Sillery, Comte de Genlis, stood up, yawned, stretched. ‘Thanks, Mirabeau. Time to get down to the serious drinking now. Camille, you coming back with us?’

The invitation seemed to be general. It excluded two people: the Candle of Arras (who was at that moment absent) and the Torch of Provence. The Genevans, self-excluded, stood up and bowed and said their good-nights; they began to fold their napkins and pick up their hats, to adjust their cravats, to twitch at their stockings. Suddenly Mirabeau detested them. He detested their grey silk frock-coats and their exactitude and their grovelling attention to all his demands, he wanted to squash their hats over their eyes and roar out into the night, one comradely arm around his milliner and the other around a bestselling novelist. And this was odd, really; if there was anyone he couldn’t stand, it was Laclos, and if there was anyone he would have hated to get drunk with, it was Camille. These wild feelings could only be, he thought, the product of a well-mannered and abstemious evening spent cultivating Maximilien Robespierre.

By the time Robespierre got back, the room would have emptied. They’d be left to exchange a dry little English handshake. Take care of yourself, Candle. Mind how you go, Torch.

THEY HAD TO GET the cards out, of course; de Sillery would never go to bed at all if they didn’t. After he had indulged his losing streak, he sat back in his chair and started laughing. ‘How annoyed Mr Miles and the Elliots would be, if they knew what I did with the King of England’s money.’

‘I imagine they have a pretty good idea what you do with it.’ Laclos shuffled the pack. ‘They don’t suppose you devote it to charitable work.’

‘Who is Mr Miles?’ Camille asked.

Laclos and de Sillery exchanged a glance. ‘I think you should tell him,’ Laclos said. ‘Camille should not live like a careless king, in gross ignorance of where the money comes from.’

‘It’s very complicated.’ Reluctantly, de Sillery laid his cards face-down on the table. ‘You know Mrs Elliot, the charming Grace? No doubt you’ve seen her flitting around the town gathering the political gossip. She does this because she works for the English government. Her various liaisons, you see, have put her in such an interesting position. She was the Prince of Wales’s mistress before Philippe brought her to France. Now, of course, Agnès de Buffon is mistress – my wife Félicité arranges these things – but Grace and the Duke are still on the best of terms. Now,’ he paused, and rubbed his forehead tiredly, ‘Mrs Elliott has two brothers-in-law, Gilbert and Hugh. Hugh lives in Paris, Gilbert comes over every few weeks. And there is another Englishman with whom they associate, a Mr Miles. They are all agents for the British Foreign Office. They are here to observe events, make reports and convey funds to us.’

‘Well done, Charles-Alexis,’ Laclos said. ‘Admirably lucid. More claret?’

Camille said, ‘Why?’

‘Because the English are deeply interested in our Revolution,’ de Sillery said. ‘Yes, go on Laclos, push the bottle over. You may think they want us to enjoy the blessings of a Parliament and a constitution like theirs, but it is hardly that; they are interested in anything that undermines Louis’s position. As is Berlin. As is Vienna. It might be an excellent thing for the English if we dispensed with King Louis and replaced him by King Philippe.’

Deputy Pétion looked up slowly. His large handsome face was creased with scruple. ‘Did you bring us here to burden us with this information?’

‘No,’ Camille said. ‘He is telling us because he has had too much to drink.’

‘’Tisn’t a burden,’ Charles-Alexis said. ‘It’s pretty well generally known. Ask Brissot.’

‘I have a great deal of respect for Brissot,’ Deputy Pétion insisted.

‘Have you so?’ Laclos murmured.

‘He doesn’t seem to me to be the type of man who would engage in this sort of deviousness.’

‘Dear Brissot,’ Laclos said. ‘So unworldly is he that he thinks money appears in his pocket by spontaneous generation. Oh, he knows – but he doesn’t admit he knows. He takes care never to make inquiries. If you want to give him a fright, Camille, just walk up to him and say in his ear “William Augustus Miles”.’

‘If I may make a point,’ Pétion interposed, ‘Brissot has not the air of a man receiving money. I only ever see him in the one coat, and that is almost out at elbows.’

‘Oh, we don’t pay him much,’ Laclos said. ‘He wouldn’t know what to do with it. Unlike present company. Who have a taste for the finer things in life. You still don’t believe it, Pétion? Tell him, Camille.’

‘It’s probably true,’ Camille said. ‘He used to take money from the police. Have casual chats with his friends and report on their political opinions.’

‘Now you shock me.’ But no: Pétion’s tone was controlled.

‘How else was he to make a living?’ Laclos asked.

Charles-Alexis laughed. ‘All these writers and people, they have enough on each other to live by blackmail and get rich. Not so, Camille? They only desist out of fear of being blackmailed back.’

‘But you are drawing me into something…’ For a moment Pétion looked sober. He rested his forehead in the palm of his hand. ‘If I could only think straight about this.’

‘It doesn’t permit straight thinking,’ Camille said. ‘Try some other kind.’

Pétion said, ‘It will be so difficult to keep any kind of…integrity.’

Laclos poured him another drink. Camille said, ‘I want to start a newspaper.’

‘And whom did you envisage as your backer?’ Laclos said smoothly. He liked to hear people admit they needed the Duke’s money.

‘The Duke’s lucky I’ll take his money,’ Camille said, ‘when there are so many other sources. We may need the Duke, but how much more does the Duke need us.’

‘Collectively, he may need you,’ Laclos said in the same tone. ‘Individually he does not need you at all. Individually you may all jump off the Pont-Neuf and drown your sorry selves. Individually, you can be replaced.’

‘Oh, you think so?’

‘Yes, Camille, I do think so. You have a prodigiously inflated idea of your own place in the scheme of things.’

Charles-Alexis leaned forward, put a hand on Laclos’s arm. ‘Careful, old thing. Change of subject?’ Laclos swallowed mutinously. He sat in silence, brightening only a little as de Sillery told stories of his wife. Félicité, he said, had kept stacks of notebooks under the marital bed. Sometimes she groped for them as you lay on top of her, labouring in pursuit of ecstasy. Did the Duke find this, he wondered, as off-putting as he always had?

‘Your wife’s a tiresome woman,’ Laclos said. ‘And Mirabeau says he’s had her.’

‘Very likely, very likely,’ de Sillery said. ‘He’s had everybody else. Still, she doesn’t do much these days. She’s happier organizing it for other people. When I think, my God, when I think back on my life…’ He fell into a short reverie. ‘Could I ever have imagined I’d end up married to the best-read procuress in Europe?’

‘By the way, Camille,’ Laclos said, ‘Agnès de Buffon was twittering on about your last pamphlet. The prose. She thinks she’s a judge. We must introduce you.’

‘And to Grace Elliot,’ de Sillery said. He and Laclos laughed.

‘They’ll eat him alive,’ Laclos said.

At dawn Laclos opened a window and draped his elegant body out over the town, breathing in the King’s air in gasps. ‘No persons in Versailles,’ he announced, ‘are so inebriated as we. Let me tell you, my pirate crew, every dog has his day, and Philippe’s is at hand, soon, soon, August, September, October.’

CAMILLE’S new pamphlet came out in September. It bore the title ‘A Lecture to Parisians, by the Lanterne’ and this epigraph from St Matthew: ‘Qui male agit odit lucem.’ Loosely translated by the author: scoundrels abhor the Lanterne. The iron gibbet on the Place de Grève announced itself ready to bear further burdens. It suggested their names. The author’s name did not appear; he signed himself ‘My Lord Prosecutor to the Lanterne’.

At Versailles, Antoinette read the first two pages only. ‘In the normal way of things,’ she said to Louis, ‘this writer would be put in prison for a very long time.’

The King was reading a geography book. He glanced up. ‘Then we must consult Lafayette, I suppose.’

‘Are you out of your mind?’ his wife asked him coldly: they had developed, in these exigencies, a fairly ordinary manner of talking. ‘The Marquis is our sworn enemy. He pays creatures such as this to slander us.’

‘So does the Duke,’ the King said in a low voice. He found it hard to pronounce Philippe’s name. ‘Our red cousin,’ the Queen called him. ‘Which is the more dangerous?’

They pondered. The Queen thought it was Lafayette.

LAFAYETTE read the pamphlet and hummed tunelessly under his breath. He took it to Mayor Bailly. ‘Too dangerous,’ the mayor said.

‘I agree.’

‘I mean, to arrest him would be too dangerous. The Cordeliers section, you know. He’s moved in.’

‘With respect, M. Bailly, I say this writing is treasonable.’

‘I can only say, General, that it came pretty near the bone last month when the Marquis de Saint-Huruge sent me an open letter telling me to oppose the King’s veto or be lynched. As you’re aware, when we arrested the man the Cordeliers made so much trouble I thought it best to let him go again. I don’t like it, but there you are. That whole district is spoiling for a fight. Do you know this man Danton, the Cordeliers’ president?’

‘Yes,’ Lafayette said. ‘I do indeed.’

Bailly shook his head. ‘We must exercise caution. We can’t handle any more riots. We mustn’t make martyrs, you see.’

‘I’m compelled to admit,’ Lafayette said, ‘that there’s sense in what you say. If all the people Desmoulins threatens were strung up tomorrow, it would hardly be a Massacre of the Innocents. So we do nothing. But then our position becomes impossible, because we shall be accused of countenancing mob law.’

‘So what would you like to do?’

‘Oh, I would like…’ Lafayette closed his eyes. ‘I would like to send three or four stout fellows across the river with instructions to reduce My Lord Prosecutor to a little red stain on the wall.’

‘My dear Marquis!’

‘You know I don’t mean it,’ Lafayette said regretfully. ‘But sometimes I wish I were not such an Honourable Gentleman. I often wonder how civilized methods will answer, in dealing with these people.’

‘You are the most honourable gentleman in France,’ the mayor said stiffly. ‘That is generally known.’ Universally, he would have said, had he not been an astronomer.

‘Why do you think we have such trouble with the Cordeliers section?’ Lafayette asked. ‘There’s this man Danton, and that abortion Marat, and this – ’ he indicated the paper. ‘By the way, when this is at Versailles it stays with Mirabeau, which may tell us something about Mirabeau.’

‘I will make a note of it. You know,’ the mayor said mildly, ‘considered as literature, the pamphlet is admirable.’

‘Don’t tell me about literature,’ Lafayette said. He was thinking of Berthier’s corpse, the bowels trailing from the gashed abdomen. He leaned forward and flicked up the pamphlet with his fingertips. ‘Do you know Camille Desmoulins?’ he asked. ‘Have you seen him? He’s one of these law-school boys. Never used anything more dangerous than a paperknife.’ He shook his head wonderingly. ‘Where do they come from, these people? They’re virgins. They’ve never been to war. They’ve never been on the hunting field. They’ve never killed an animal, let alone a man. But they’re such enthusiasts for murder.’

‘As long as they don’t have to do it themselves, I suppose,’ the mayor said. He remembered the dissected heart on his desk, a shivering lump of butcher’s meat.

IN GUISE: ‘How am I to hold my head up on the street?’ Jean-Nicolas asked rhetorically. ‘The worse of it is, he thinks I should be proud of him. He’s known everywhere, he says. He dines with aristocrats every day.’

‘As long as he’s eating,’ Mme Desmoulins said. Proceeding out of her own mouth, the comment surprised her. She had never been one for taking a maternal interest. And equally, Camille had never been one to eat.

‘I don’t know how I’m to face the Godards. They’ll all have read it. There’s one thing, though – I bet Rose-Fleur’s glad now that they made her break it off.’

‘How little you understand women!’ his wife said.

Rose-Fleur Godard kept the pamphlet on her sewing-table and quoted it in and out of season, to annoy M. Tarrieux de Tailland, her new fiancé.

D’ANTON had read the pamphlet and given it to Gabrielle to read. ‘You’d better,’ he said. ‘Everybody will be talking about it.’

Gabrielle read half, then left it aside. Her reasoning was this: she had, in a manner of speaking, to live with Camille, and she would therefore prefer not to know too much of his opinions. She was quiet now; feeling her way from day to day, like a blind woman in a new house. She never asked Georges what had happened at the meetings of the District Assembly. When new faces appeared at the supper table she simply laid extra places, and tried to keep the conversation light. She was pregnant again. No one expected much of her. No one expected her to bother her head about the state of the nation.

THE FAMOUS WRITER, Mercier, introduced Camille into the salons of Paris and Versailles. ‘In twenty years time,’ Mercier predicted, ‘he will be our foremost man of letters.’ Twenty years? Camille can’t wait twenty minutes.

His mood, at these gatherings, would swing violently, from moment to moment. He would feel exhilarated; then he would feel he was there under false pretences. Society hostesses, who had taken such pains to get him, often felt obliged to pretend not to know who he was. The idea was that his identity should seep and creep out, gradually, so that if anyone wanted to walk out they could do it without making a scene. But the hostesses must have him; they must have the frisson, the shock-value. A party isn’t a party…

His headache had come back; too much hair-tossing, perhaps. The one constant, at these parties, was that he didn’t have to say anything. Other people did the talking, around him. About him.

Friday evening, late, the Comtesse de Beauharnais’s house: full of young poets to flatter her, and interesting rich Creoles. The airy rooms shimmered: silver, palest blue. Fanny de Beauharnais took his arm: a proprietorial gesture, so different from when no one wanted to own him.

‘Arthur Dillon,’ she whispered. ‘You’ve not met? Son of the eleventh Viscount Dillon? Sits in the Assembly for Martinique?’ A touch, a whisper, a rustle of silk: ‘General Dillon? Here is something to pique your curiosity.’

Dillon turned. He was forty years old, a man of singular and refined good looks; almost a caricature aristocrat, with his thin beak of a nose and his small red mouth. ‘The Lanterne Attorney,’ Fanny whispered. ‘Don’t tell everybody. Not all at once.’

Dillon looked him over. ‘Damned if you’re what I expected.’ Fanny glided away, a little cloud of perfume billowing in her wake. Dillon’s gaze had become fixed, fascinated. ‘The times change, and we with them,’ he remarked in Latin. He slid a hand on to Camille’s shoulder, took him into custody. ‘Come and meet my wife.’

Laure Dillon occupied a chaise-longue. She wore a white muslin dress spangled with silver; her hair was caught up in a turban of white-and-silver silk gauze. Reclining, Laure was exercising her foible: she carried round with her the stump of a wax candle and, when unoccupied, nibbled it.

‘My dear,’ Dillon said, ‘here’s the Lanterne Attorney.’

Laure stirred a little crossly: ‘Who?’

‘The one who started the riots before the Bastille fell. The one who has people strung up and their heads cut off and so forth.’

‘Oh,’ Laure looked up. The silver hoops of her earrings shivered in the light. Her beautiful eyes wandered over him. ‘Sweet,’ she said.

Arthur laughed a little. ‘Not much on politics, my wife.’

Laure unglued from her soft lips the warm piece of wax. She sighed; absent-mindedly she fondled the ribbon at the neck of her dress. ‘Come to dinner,’ she said.

As Dillon steered him back across the room, Camille caught sight of himself: his wan, dark, sharp face. The clocks tinkled eleven. ‘Almost time for supper,’ Dillon said. He turned, and saw on the Lanterne Attorney’s face a look of the most heart-rending bewilderment. ‘Don’t look like that,’ he said earnestly. ‘It’s power, you see. You’ve got it now. It changes things.’

‘I know. I can’t get used to it.’

Everywhere he went there was this covert scrutiny, the dropped voices, the glances over shoulders. Who? That? Really?

The general observed him, only minutes later, in the centre of a crowd of women. It seemed that his identity was now known. There was colour in their cheeks, their mouths were slightly ajar, their pulses fluttered at proximity merely. An unedifying spectacle, the general thought: but that’s women for you. Three months ago, they’d not have given the boy a second glance.

The general was a kind man. He had undertaken to worry and wonder about Camille, and from that night on – at intervals, over the next five years – he would remember to do so. When he thought about Camille he wanted – stupid as it might seem – to protect him.

SHOULD KING LOUIS have the power to veto the actions of the National Assembly?

‘Mme Veto’ was the Queen’s new name, on the streets.

If there were no veto, Mirabeau said obscurely, one might as well live at Constantinople. But since the people of Paris were solidly opposed to the veto (by and large they thought it was a new tax) Mirabeau cobbled together for the Assembly a speech which was all things to all men, less the work of a statesman than of a country-fair contortionist. In the end, a compromise emerged: the King was left with the power not to block but to delay legislation. Nobody was happy.

Public confusion deepened. Paris, a street-corner orator: ‘Only last week the aristocrats were given these Suspensive Vetoes, and already they’re using them to buy up all the corn and send it out of the country. That’s why we’re short of bread.’

OCTOBER: no one quite knew whether the King was contemplating resistance, or flight. In any event, there were new regiments at Versailles, and when the Flanders Regiment arrived the King’s Bodyguard gave a banquet for them at the palace.

It was a conspicuous affair, lacking in tact: though the pamphleteers would have bawled Bacchanalia at a packed lunch in the grounds.

When the King appeared, with his wife and the little Dauphin, he was cheered to the echo by inebriated military voices. The child was lifted on to the tables, and walked down them, laughing. Glasses were raised to the confusion of rebels. The tricolour cockade was thrown to the floor and ground under the gentlemen’s heels.

That is Saturday, 3 October: Versailles banqueting while Paris starves.

Five o’clock that evening, President Danton was roaring at his District Assembly, his doubled fist pounding the table. The Cordeliers citizens will placard the city, he said. They will revenge this insult to the patriots. They will save Paris from the royal threat. The battalion will call out its brothers-in-arms in every district, they will be the first on the road. They will hale the King to Paris, and have him under their eye. If all else fails it is clear that President Danton will march there himself, and drag Louis back single-handed. I have finished with the King, said the King’s Councillor.

Stanislas Maillard, an officer of the Châtelet court, preached to the market-women. He referred, needlessly, to their hungry children. A procession formed. Maillard was a long, gaunt figure, like Death in a picture-book. On his right was a tinker woman, a tramp, known to the down-and-outs as the Queen of Hungary. On his left was a brain-damaged escapee from an asylum, clutching in his hand a bottle of the cheapest spirits. The liquor ran from his nerveless mouth down his chin, and in his flint-coloured eyes there was no expression at all. Sunday.

Monday morning: ‘I suppose you think you are going somewhere?’ Danton asked his clerks.

They had thought of a day at Versailles, actually.

‘Is this a legal practice, or a field headquarters?’

‘Danton has an important shipping case,’ Paré told Camille, later in the morning. ‘He is not to be disturbed. You weren’t really thinking of going there yourself, were you?’

‘It was just that he gave the impression, at the District Assembly – well, no, I wasn’t, not really. By the way, is this the same shipping case he had when the Bastille was taken?’

‘The appeal,’ Danton said, from behind his bolted door.

SANTERRE, a National Guard battalion commander, leads an assault on City Hall; some money is stolen and papers are torn up. The market-women run through the streets, sweeping up the women they meet, exhorting and threatening them. In the Place de Grève the crowd is collecting arms. They want the National Guard to go to Versailles with them, Lafayette at their head. From nine a.m. to eleven a.m. the Marquis argues with them. A young man tells him, ‘The government is deceiving us – we’ve got to go and bring the King to Paris. If, as they say, he’s an imbecile, then we’ll have his son for King, you’ll be Regent, everything will be better.’

At eleven a.m., Lafayette goes to argue with the Police Committee. All afternoon he is barricaded in, gets the news only in snatches. But by five o’clock he is on the road to Versailles, at the head of fifteen thousand National Guardsmen. The number of the mob is uncounted. It is raining.

An advance party of women have already invaded the Assembly. They are sitting on the deputies’ benches, with sodden skirts hitched up and legs spread out, jostling the deputies and making jokes, calling for Mirabeau. A small delegation of the women is admitted to the King’s presence, and he promises them all the bread that can be found. Bread or blood? Théroigne is outside, talking to soldiers. She wears a scarlet riding-habit. She is in possession of a sabre. The rain is spoiling the plumes on her hat.

A message to General Lafayette, on the road: the King has decided after all to accept the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Oh really? To the general, weary and dispirited, his hands frozen on the harness and rain running down his pointed nose, it is not the most relevant piece of news.

PARIS: Fabre talking round the cafés, making opinion. ‘The point is,’ he said, ‘one initiates something like this, one should take the credit. Who can deny that the initiative was seized by President Danton and his district? As for the march itself, who better than the women of Paris to undertake it? They won’t fire on women.’

Fabre felt no disappointment that Danton had stayed at home; he felt relief. He began to sense dimly the drift of events. Camille was right; in public, before his appropriate audience, Danton had the aura of greatness about him. From now on, Fabre would always urge him to think of his physical safety.

NIGHT. Still raining. Lafayette’s men waiting in the darkness, while he is interrogated by the Assembly. What is the reason for this unseemly military demonstration?

In his pocket Lafayette has a desperate note from the president of this same Assembly, begging him to march his men to Versailles and rescue the King. He would like to put his hand in his pocket, to be sure that the message is not a dream, but he cannot do that in front of the Assembly; they would think he was being disrespectful. What would Washington do? he asks himself: without result. So he stands, mud-spattered up to his shoulders, and answers these strange questions as best he can, pleading with the Assembly in an increasingly husky voice – could the King, to save a lot of trouble, be persuaded to make a short speech in favour of the new national colours?

A little later, exhausted, he is assisted into the presence of the King and, still covered in mud, addresses himself to His Majesty, His Majesty’s brother the Comte de Provence, the Archbishop of Bordeaux and M. Necker. ‘Well,’ the King says, ‘I suppose you’ve done what you could.’

Become semi-articulate, the general clasps his hands to his breast in an attitude he has hitherto seen only in paintings, and pledges his life as surety for the King’s – he is also the devoted servant of the constitution, and someone, someone, he says, has been paying out a great deal of money.

The Queen stood in the shadows, looking at him with dislike.

He went out, fixed patrols about the palace and the town, watched from a window the low burning of torches and heard drunken singing on the night wind. Ballads, no doubt, relating to Court life. Melancholy swept him, a sort of nostalgia for heroism. He checked his patrols, visited the royal apartments once more. He was not admitted; they had retired for the night.

Towards dawn, he threw himself down fully clothed and shut his eyes. General Morpheus, they called him later.

Sunrise. Drumbeats. One small gate is left unguarded, by negligence or treachery; shooting breaks out, the Bodyguard are overwhelmed, and within minutes there are heads on pikes. The mob are in the palace. Women armed with knives and clubs are sprinting through the galleries towards their victims.

The general awake. Move, and at the double. Before he arrives the mob have reached the door of the Salon de la uil de Boeuf, and the National Guardsmen have driven them back. ‘Give me the Queen’s liver,’ a woman screams. ‘I want it for a fricassee.’ Lafayette – on foot, no time to wait for a horse to be saddled – is not yet inside the château, for he is caught up in a screaming mob who have already got nooses round the necks of members of the Bodyguard. The royal family are safe – just – inside the salon. The royal children are crying. The Queen is barefoot. She has escaped death by the thickness of a door.

Lafayette arrives. He meets the eyes of the barefoot woman – the woman who drove him from Court, who once ridiculed his manners and laughed at his dancing. Now she requires of him more than a courtier’s skills. The mob seethes beneath the windows. Lafayette indicates the balcony. ‘It is necessary,’ he says.

The King steps out. The people shout, ‘To Paris.’ They wave pikes and level guns. They call for the Queen.

Inside the room, the general makes a gesture of invitation to her. ‘Don’t you hear what they are shouting?’ she says. ‘Have you seen the gestures they make?’

‘Yes.’ Lafayette draws his finger across his throat. ‘But either you go to them, or they come for you. Step out, Madame.’

Her face frozen, she takes her children by the hands, steps out on to the balcony. ‘No children!’ the mob call. The Queen drops the Dauphin’s hand; he and his sister are drawn back inside the room.

Antoinette stands alone. Lafayette’s mind is racing to consequences – all hell will be let loose, there will be total war by nightfall. He steps out beside her, hoping to shield her with his body if the worst…and the people howl…and then – O perfect courtier! – he takes the Queen’s hand, he raises it, he bows low, he kisses her fingertips.

Immediately, the mood swings around. ‘Vive Lafayette!’ He shivers at their fickleness; shivers inside. And ‘Vive la reine,’ someone calls. ‘Vive la reine!’ That cry has not been heard in a decade. Her fists unclench, her mouth opens a little; he feels her lean against him, floppy with relief. A Bodyguard steps out to assist her, a tricolour cockade in his hat. The crowd cheer. The Queen is handed back inside. The King declares he will go to Paris.

This takes all day.

On the way to Paris Lafayette rides by the King’s carriage, and speaks hardly a word. There will be no bodyguards after this, he thinks, except those I provide. I have the nation to protect from the King, and now the King to protect from the people. I saved her life, he thinks. He sees again the white face, the bare feet, feels her sag against him as the crowd cheer. She will never forgive him, he knows. The armed forces are now at my disposal, he thinks, my position should be unassailable…but slouching along in the halfdark, the anonymous many, the People. ‘Here we have them,’ they cry, ‘the baker, the baker’s wife, and the baker’s little apprentice.’ The National Guardsmen and the Bodyguards exchange hats, and thus make themselves look ridiculous: but more ridiculous still are the bloody defaced heads that bob, league upon league, before the royal carriage.

That was October.

THE ASSEMBLY followed the King to Paris, and took up temporary lodgings in the archbishop’s palace. The Breton Club resumed its meetings in the refectory of an empty conventual building in the rue Saint-Jacques. The former tenants, Dominicans, were always called by the people ‘Jacobins’, and the name stuck to the deputies and journalists and men of affairs who debated there like a second Assembly. They moved, as their numbers grew, into the library; and finally into the old chapel, which had a gallery for the public.

In November the Assembly moved to the premises of what had formerly been an indoor riding-school. The hall was cramped and badly lit, an inconvenient shape, difficult to speak in. Members faced each other across a gangway. One side of the room was broken by the president’s seat and the secretaries’ table, the other by the speaker’s rostrum. The stricter upholders of royal power sat on the right of the gangway; the patriots, as they often called themselves, sat on the left.

Heat was provided by a stove in the middle of the floor, and ventilation was poor. At Dr Guillotin’s suggestion, vinegar and herbs were sprinkled twice daily. The public galleries were cramped too, and the three hundred spectators they held could be organized and policed – not necessarily by the authorities.

From now on the Parisians never called the Assembly anything but ‘the Riding-School’.

RUE CONDÉ: towards the end of the year, Claude permitted a thaw in relations. Annette gave a party. His daughters asked their friends, and the friends asked their friends. Annette looked around: ‘Suppose a fire were to break out?’ she said. ‘So much of the Revolution would go up in smoke.’

There had been, before the guests arrived, the usual row with Lucile; nothing was accomplished nowadays without one. ‘Let me put your hair up,’ Annette wheedled. ‘Like I used to? With flowers?’

Lucile said vehemently that she would rather die. She didn’t want pins, ribbons, blossoms, devices. She wanted a mane that she could toss about, and if she was willing to torture a few curls into it, Annette thought, that was only for greater verisimilitude. ‘Oh really,’ she said crossly, ‘if you’re going to impersonate Camille, at least get it right. If you go on like that you’ll get a crick in your neck.’ Adèle put her hand over her mouth, and snorted with mirth. ‘You’ve got to do it like this,’ Annette said, demonstrating. ‘You don’t simultaneously toss your head back and shake the hair out of your eyes. The movements are actually quite separate.’

Lucile tried it, smirking. ‘You could be right. Adèle, you have a go. Stand up, you have to stand up to get the effect.’

The three women jostled for the mirror. They began to splutter with laughter, then to shriek and wail. ‘Then there’s this one,’ Lucile said. ‘Out of my way, minions, while I show you.’ She wiped the smile from her face, stared into the mirror in a rapture of wide-eyed narcissism, and removed an imaginary tendril of hair with a delicate flick.

‘Imbecile,’ her mother said. ‘Your wrist’s at quite the wrong angle. Haven’t you eyes to see?’

Lucile opened her eyes very wide and gave her a Camille-look. ‘I was only born yesterday,’ she said pitifully.

Adèle and her mother staggered around the room. Adèle fell on to Annette’s bed and sobbed into the pillow. ‘Oh, stop it, stop it,’ Annette said. Her hair had fallen down and tears were running through her rouge. Lucile subsided to the floor and beat the carpet with her fist. ‘I think I’ll die,’ she said.

Oh, the relief of it! When for months now, the three of them had hardly spoken! They got to their feet, tried to compose themselves; but as they reached for powder and scent, great gouts of laughter burst from one or the other. All evening they’re not safe: ‘Maître Danton, you know Maximilien Robespierre, don’t you?’ Annette said, and turned away because tears were beginning to well up in her eyes and her lips were twitching and another scream of laughter was about to be born. Maître Danton had this exceedingly aggressive habit of planting a fist on his hip and frowning, while he was talking about the weather or something equally routine. Deputy Maximilien Robespierre had the most curious way of not blinking, and a way of insinuating himself around the furniture; it would be marvellous to see him spring on a mouse. She left them to their self-importance, guffawing inside.

‘So where are you living now?’ Danton inquired.

‘On the rue Saintonge in the Marais.’

‘Comfortable?’

Robespierre didn’t reply. He couldn’t think what Danton’s standard of comfort might be, so anything he said wouldn’t mean much. Scruples like this were always tripping him up, in the simplest conversations. Luckily, Danton seemed not to want a reply. ‘Most of the deputies don’t seem very happy about moving to Paris.’

‘Most of them aren’t there half the time. When they are they don’t pay attention. They sit gossiping to each other about clarifying wine and fattening pigs.’

‘They’re thinking of home. After all, this is an interruption to their lives.’

Robespierre smiled faintly. He was not supercilious, he just thought that was a peculiar way of looking at things. ‘But this is their life.’

‘But you can understand it – they think about the farm going to seed and the children growing up and the wife hopping into bed with all and sundry – they’re only human.’

Robespierre flicked a glance up at him. ‘Really, Danton, the times being what they are, I think we could all do with being a bit more than that.’

Annette moved amongst her guests, trying to discipline her grin to a social smile. Somehow it no longer seemed possible to see her male guests as they wished to be seen. Deputy Pétion (self-regarding smirk) seemed amiable; so did Brissot (a whole set of little tics and twitches). Danton was watching her across the room. Wonder what he’s thinking? She had a shrewd idea. She imagined Maître Danton’s drawl: ‘Not a bad-looking woman, considering her age.’ Fréron stood alone, conspicuously alone; his eyes followed Lucile.

Camille, as usual these days, had an audience. ‘All we really have to do is decide on a title,’ he said. ‘And organize the provincial subscriptions. It’s going to come out every Saturday, though more often when events require it. It will be in octavo, with a grey paper cover. Brissot is going to write for us, and Fréron, and Marat. We shall invite correspondence from readers. We shall carry particularly scathing theatre reviews. The universe and all its follies shall be comprehended in the pages of this hyper-critical journal.’

‘Will it make money?’ Claude asked.

‘Oh, not at all,’ Camille said happily. ‘I don’t even expect to cover costs. The idea is to keep the cover price as low as possible, so that nearly everybody will be able to afford it.’

‘How are you going to pay your printer, then?’

Camille looked mysterious. ‘There are sources,’ he said. ‘The idea really is to let people pay you to write what you were going to write anyway.’

‘You frighten me,’ Claude said. ‘You appear to have no moral sense whatever.’

‘The end result will be good. I won’t have to spend more than a few columns paying compliments to my backers. The rest of the paper I can use to give some publicity to Deputy Robespierre.’

Claude looked around fearfully. There was Deputy Robespierre, in conversation with his daughter Adèle. Their conversation seemed confidential – intimate almost. But then – he had to admit it – if you could separate Deputy Robespierre’s speeches at the Riding-School from the deputy’s own person, there was nothing at all alarming about him. Quite the reverse really. He is a neat, quiet young man; he seems equable, mild, responsible. Adèle is always bringing his name into the conversation; she must, obviously, have feelings towards him. He has no money, but then, you can’t have everything. You have to be glad simply to have a son-in-law who isn’t physically violent.

Adèle had found her way to Robespierre by easy conversational stages. What were they talking about? Lucile. ‘It’s fearful,’ she was saying. ‘Today – well, today was different, actually we had a good laugh.’ I won’t tell him what about, she decided. ‘But normally the atmosphere’s quite frightening. Lucile’s so strong-willed, she argues all the time. And she’s really made her mind up on him.’

‘I thought that, as he’d been asked here today, your father was softening a little.’

‘So did I. But now look at his face.’ They glanced across the room at Claude, then turned back and nodded to each other gloomily. ‘Still,’ Adèle said, ‘they’ll get their way in the end. They’re the kind of people who do. What worries me is, what will the marriage be like?’

‘The thing is,’ Robespierre said, ‘that everyone seems to regard Camille as a problem. But he isn’t a problem to me. He’s the best friend I’ve ever had.’

‘Aren’t you nice to say so?’ And yes, isn’t he, she thought. Who else would venture so artless a statement, in these complicated days? ‘Look,’ she said. ‘Look over there. Camille and my mother are talking about us.’

So they were; heads together, just like in the old days. ‘Matchmaking is the province of elderly spinsters,’ Annette was saying.

‘Don’t you know one you could call in? I like things done correctly.’

‘But he’ll take her away. To Artois.’

‘So? One may travel there. Do you think there’s a steep cliff around Paris, and at Chaillot you drop off into hell? Besides, I don’t think he’ll ever go back home.’

‘But what about when the constitution’s made, and the Assembly dissolves?’

‘I don’t think it will work like that, you see.’

Lucile watched. Oh, mother, she thought, can’t you get any closer? Why don’t you just grapple him to the carpet, and have done with it? The earlier bonhomie had evaporated, as far as she was concerned. She didn’t want to be in this room, with all these chattering people. She looked around for the quietest possible corner. Fréron followed her.

She sat; managed a strained smile. He stretched a proprietorial arm along the back of her chair; lounging, making small-talk, his eyes on the room and not on her. But from time to time his eyes flickered downwards. Finally, softly, insinuatingly, he said, ‘Still a virgin, Lucile?’

Lucile blushed deeply. She bent her head. Not so far from the proper little miss, then? ‘Most emphatically,’ she said.

‘This is not the Camille I know.’

‘He’s saving me till I’m married.’

‘That’s all very well for him, I suppose. He’s got – outlets, hasn’t he?’

‘I don’t want to know this,’ she said.

‘Probably better not. But you’re a grown-up girl now. Don’t you find the delights of your maiden state begin to pall?’

‘What do you suggest I do about it, Rabbit? What opportunities do you think I have?’

‘Oh, I know you find ways to see him. I know you slip out now and again. I thought, at the Danton’s place perhaps. He and Gabrielle are not excessively moral.’

Lucile gave him a sideways glance, as devoid of expression as she could make it. She would not have taken part in this conversation – except that it was a painful relief to talk about her feelings to anyone, even a persecutor. Why must he slander Gabrielle? Rabbit will say anything, she decided. Even he realized he had gone too far – she could see it in his face. Just imagine, she thought – ‘Gabrielle, can we come round tomorrow and borrow your bed?’ Gabrielle would die sooner.

The thought of the Dantons’ bed gives her, she admits, a very strange feeling. An indescribable feeling, really. The thought crosses her mind that, when that day comes, Camille won’t hurt her but Danton will – and her heart bounds, she blushes again, more furiously, because she doesn’t know where the idea came from, she didn’t ask for it, she didn’t want to think that thought at all.

‘Has something upset you?’ Fréron says.

She snaps: ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself.’ Still, she can’t erase the picture from her mind: that belligerent energy, those huge hard hands, that weight. A woman must thank God, she says to herself, that she has a limited imagination.

THE NEWSPAPER went through various changes of name. It began as the Courier du Brabant – they were having a revolution over the border, too, and Camille thought it worth a mention. It became the Révolutions de France et du Brabant, ended up simply as the Révolutions de France. Of course, Marat was the same, always changing his title, for various shady reasons. He had been the Paris Publicist, was now the People’s Friend. A title, they thought at the Révolutions, of risible naïveté; it sounded like a cure for the clap.

Everyone is starting newspapers, including people who can’t write and who, says Camille, can’t even think. The Révolutions stands out; it makes a splash; it also imposes a routine. If the staff is small, temporary and a bit disorganized, this hardly matters; at a push, Camille can write a whole issue himself. What’s thirty-two pages (in octavo) to a man with so much to say for himself?

Monday and Tuesday they were in the office early, working on the week’s edition. By Wednesday the greater part was ready for the printer. On Wednesday, also, the writs came in from the previous Saturday’s libels, though it had been known for the victims to drag their lawyers back from the country on a Sunday morning and get writs served by Tuesday. Challenges to duels came in sporadically, throughout the week.

Thursday was press day. They made the last-minute corrections, then a menial would sprint around to the printer, M. Laffrey, whose premises were on the Quai des Augustins. Thursday midday brought Laffrey and the distributor, M. Garnery, both tearing their hair. Do you want to see the presses impounded, do you want us in gaol? Sit down, have a drink, Camille would say. He rarely agreed to changes; almost never. And they knew that the bigger the risk, the more copies they’d sell.

René Hébert would come into the office: pink-skinned, unpleasant. He made snide jokes all the time about Camille’s private life; no sentence lacked its double-entendre. Camille explained him to his assistants; he used to work in a theatre box-office, but he was sacked for stealing from the petty cash.

‘Why do you put up with him?’ they said. ‘Next time he comes, shall we throw him out?’

They were like that at the Révolutions; always hoping for a less sedentary occupation.

‘Ah, no, leave him alone,’ Camille said. ‘He’s always been offensive. It’s his nature.’

‘I want my own newspaper,’ Hébert said. ‘It will be different from this.’

Brissot was in that day, perched on a desk, twitching. ‘Shouldn’t be too different,’ he said. ‘This one is a pre-eminent success.’

Brissot and Hébert didn’t like each other.

‘You and Camille write for the educated,’ Hébert said. ‘So does Marat. I’m not going to do that.’

‘You are going to start a newspaper for the illiterate?’ Camille asked him sweetly. ‘I wish you every success.’

‘I’m going to write for the people in the street. In the language they speak.’

‘Then every other word will be an obscenity,’ Brissot said, sniffing.

‘Precisely,’ Hébert said, tripping out.