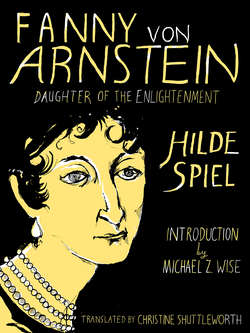

Читать книгу Fanny von Arnstein: Daughter of the Enlightenment - Hilde Spiel - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеIN THE GENTLE LIGHT OF EVERYDAY LIFE, WE ARE BORNE ALONG BY two realities. One accompanies us from the day of our entrance into the world to our dying day. The other flows around us from the beginnings of humanity and through us until the end of all earthly life. Over most of us the stream of history rushes on its way uncaring; it washes the traces of our existence into the depths, to efface them forever. We alter its course as little as would a small pebble, loosened from the bank and driven along with the current for a while.

To halt the course of world events, or even to turn them in a new direction, is granted only to few. Like dams, boulders or continually whirling eddies, the impact they have on their epoch seems to interrupt the flow of history. It is not always necessary to take vigorous action in order to gain this significance. There are some who are placed by chance at a turning of the stream of time, where it is joined by more than one tributary. Like a small island, resting unharmed amid the convergence of waters, they endure as marks of a change of course. Not by their deeds, but merely by their being, they achieve immortality.

It is not however without a measure of greatness that such people earn their claim to imperishable existence. The woman whose life is recorded here did not strive to obstruct or promote the progress of events. But she was conscious of her origins, of what people, in what times and what place she was born, and she filled her place in history with grace, spirit and dignity. Her place of birth was a Europe torn by the battles of kings, by the uprising of nations, by war and revolution. Her time extended from the Dark Ages of thought through the Age of Enlightenment to the returning twilight of reaction. Her people was that of which Tacitus had said that it was like no other on earth, and which paid for its otherness with constant humiliation and mortal danger. Yet for a short moment she procured for it equality of rank. In her person the great ones of the world recognized a being of similar worth. In her they honored what had been despised for thousands of years.

When she died, Felix Mendelssohn’s mother mourned in her “the most interesting woman in Europe.” This she was not by any means. She was only to be found where Europe was most interesting. Among the heroines of emancipation in Europe she was merely the first, not the cleverest. She was no intellectual phenomenon like Rahel Varnhagen, nor a romantically fanciful one like Dorothea Schlegel, nor an erotic-sentimental one like poor Henriette Herz. She was a social phenomenon which operated by its emanations alone. It is not without reason we have no letter of hers, and very few documents from her own hand. Her ephemeral figure, her intangible charm have been preserved only in the mirror of her contemporaries. But the outward form that was hers became her image. It was neither a prophet nor a wise woman, but a great lady, who became a symbol of the liberation of women and the emancipation of the Jews.