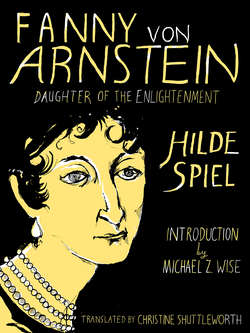

Читать книгу Fanny von Arnstein: Daughter of the Enlightenment - Hilde Spiel - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 The Mildness of the Hohenzollerns

ОглавлениеIN THE EARLY SUMMER OF 1776, A YOUNG COUPLE OF QUALITY, AND without visible flaw, were seated in a berline which was driving south, with frequent changes of horses and by deliberate daily stages by way of Dresden and Prague, to the imperial capital. The Prussian bride and Viennese bridegroom were fashionably attired: the lady in a narrow-waisted crinoline, lace sleeves and deep décolleté, the gentleman with pigtail and bag-wig, in knee-breeches which were entirely concealed by his top-boots and coat-tails; his unbuckled dagger lay beside him on the seat.

They were accompanied by a valet and lady’s-maid, who were following in a second carriage with ample luggage, as was fitting for the daughter of a man who was in a position to provide 70,000 thalers as dowry for her and each of her nine sisters; and no less so for the son of a man whose estate, a decade later, was to amount to three-quarters of a million gulden in Viennese currency. The bride had left a palais in the Burgstrasse in Berlin and a country seat near the Schlesisches Tor in order to move into an elegant town house on the Graben in Vienna. Her father, like her bridegroom’s, was well versed in associating with monarchs. He stood as near to the King’s throne as his palais to the royal residence on the Kupfergraben. He was separated from the ordinary citizen, as were the aristocracy, by an unbridgeable gulf.

A gulf also lay between the two countries to which the young couple belonged. When the bride was born, two years of the Seven Years’ War had passed. Even the peace of which she soon became conscious could not reconcile Prussia and Austria. That bitter fight in the heart of Europe, which had enriched the father of the bride as he helped his King to victory, left the two nations in deep, never quite eradicated opposition. True, both were now experiencing a fresh impetus which brought renewed prosperity to the drained provinces of one country as of the other; true, they had, together with Russia, each taken their share of helpless Poland; true, the obstinate spirit of reform of Frederick the Great was encroaching upon the hereditary lands of the Habsburgs and taking hold, if not of the Empress, at least of her son — who had twice admiringly shaken the hand of the former enemy — as well as of her Chancellor, Kaunitz, a cautious Voltairean and a patient man. But a new quarrel was at hand. Two years after the couple’s marriage, Prussian and Austrian soldiers, sent to war by their rulers for the sake of Bavaria, were to confront each other again in northern Bohemia. They did not fight; they simply dug up each other’s potatoes. But the love between the two countries did not grow any greater on that account.

The bridal couple in the berline had every reason not to become involved in these dissensions. Nevertheless, throughout their lives an invisible line of separation ran between them, which sometimes seemed to light up like a red warning signal. At seventeen years of age, the girl had exchanged her own home for an Austrian one. She was nearing fifty-seven when it was said of her, in a private communication at the time of the Congress of Vienna, that the lady was “scandaleusement prussienne.” Tall and slim, with a long, straight nose and beautiful, slightly prominent pale blue eyes, she stood out among the plump, delicately boned little Viennese ladies as a Berliner, if not as a north German, while her freshness, her ready wit and her restless vivacity unmistakably derived from the sharp clear air of her native city. The bridegroom, ten years older, but in his future marriage decidedly of more subdued powers of comprehension and slower intellect, had the good-natured, expressionless face and soft chin of so many Austrian citizens. In short, were it not for certain features such as a slight fullness of the lips or slope of the nose that almost imperceptibly hinted at a more ancient origin, they were both passable representatives of their nations. But they were not quite as passable as all that.

For when, on the second or third day of the journey, the berline stopped in front of the city gate of Dresden, the carriage was surrounded by Saxon toll-collectors who demanded the travelers’ documents, which they inspected closely with offensive glances at their elegant clothing and demeanor, finally imposing the modest but humiliating personal toll of twenty groschen. A few weeks later, in August of the same year, the same experience befell a more famous man. Moses Mendelssohn, the author of Phaedon and Kant’s successful rival for the Prussian Academy prize, was also forced at the gates of Dresden to pay the toll which was otherwise imposed only in the case of cattle and pigs. A Saxon friend of the philosopher who heard of the matter persuaded the authorities to refund the twenty groschen to Mendelssohn, whereupon the latter passed it, “increased tenfold,” to the city’s poor-box. Although the bridal couple too had, for certain reasons, in the end been excused payment, this moment made a deep impression on the girl’s mind. For in her notebook, one of the few documents from her own hand that survives, is found a verse by Moses Ephraim Kuh, who had five years earlier undergone similarly humiliating experiences elsewhere in Saxony. This touchingly naïve man, himself a Douanier of poetry, had expressed his resentment in a little dialogue between the “Zöllner [toll collector] at E.” and a traveling Jew:

Z. Du, Jude, mußt drey Thaler Zoll erlegen.

J. Drey Thaler? Soviel Geld? mein Herr, weswegen?

Z. Das fragst du noch? weil du ein Jude bist.

Wärst du ein Türk’, ein Heid’, ein Atheist,

So würden wir nicht einen Deut begehren

Als einen Juden müssen wir dich scheren.

J. Hier ist das Geld! — Lehrt euch dies euer Christ?

[T. Thou, Jew, must pay three thalers toll.

J. Three thalers? So much money? Sir, wherefore?

T. Canst thou ask that? Because thou art a Jew.

Wert thou a Turk, heathen or atheist,

We would not ask of thee a single farthing,

But as thou art a Jew, thou must be shorn.

J. Here is your money! Does your Christ teach you thus?]

The bridal couple drove on, along the Elbe, through “Saxon Switzerland” into the hereditary land of Bohemia and here, through waving yellow corn, to the old city of Prague. The June sky was blue. But a shadow had fallen over the newly married pair and accompanied them on their way, over the stony hills of the borderland into Lower Austria, through the dark green Waldviertel down into the plain as far as the river, broad and rushing, that guided them into the outskirts of Vienna. Here too, when their post-horses came to a halt at the custom-house opposite Leopoldstadt and the bride, her gaze turned upon the grey walls and high towers of the imperial residence, listened to the sentry’s brusque questions about residential authorization and toleration document, here too the shadow did not lift. It had hovered over her people since the earliest days and in the splendid, easy-going capital of the Holy Roman Empire it was even a few shades darker than at home in royal Berlin.

It was from there that, when Leopold I drove out the Viennese Jews in 1670, a number of distinguished heads of families sent a request for protection and accommodation to Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg. Sadly they complained to his ambassador in Vienna, a certain Andreas Neumann, “that the earth and the world, which God had after all created for all mankind, were equally closed against them.” The Great Elector, moved by pious mildness and political astuteness, decided that since their people had been tolerated in the electorate from the days of his ancestor Johann Georg henceforth he should provide sanctuary for fifty of them. The Marches and the duchy of Krossen, like the rest of Germany, were still suffering the consequences of the Thirty Years’ War. The land was devastated, the population scanty and impoverished; trade was languishing. Frederick William expected from the immigrants that mercantile advantage which they had been bringing for some time to his newly acquired urban community of Halberstadt. He opened his gates to the Viennese Jewry, set their annual protection fee at eight thalers, allowed them to buy houses and guaranteed their privileges for twenty years. Before this period had expired, they were absolved from the personal toll which was not abolished in Saxony until a century later.

This reasonable treatment, such as they had never received in any other part of Germany, must have gone to their heads to the extent that they began to behave as though they were human beings like any others. They began to wrangle and to squabble with each other, slandered and defrauded each other and here and there rose to riches and high position, only to leave the rest of their community behind them. In this way, in the last years of the Elector and even more so at the court of that lover of art and architecture, Frederick I, the jeweler Jost Liebmann had become very influential. The King valued him highly. Jost went in and out at court, and after his death his widow enjoyed the same favor. She rose so high that “together with her children she was accorded favorable treatment above the rest of Jewry,” and even enjoyed the privilege of appearing unannounced in Frederick’s private apartments, which particularly annoyed the Crown Prince. The Liebmannin, it is said, was a very beautiful woman, whose company was not by any means unpleasing to the King. Once the Crown Prince is said to have been ungracious to her in his father’s presence, whereat the latter reproved him for his sharpness of tone, so as to arouse in the Crown Prince “bitter feelings against anything which appeared Liebmännisch, which, however, he was only able to practice when he became King himself.”

Even though Frederick I had inherited the clemency of the Great Elector, and though he had fallen into the snares of the jeweler’s widow, the provincial regulations that he imposed upon the Jews of the Brandenburg Marches in 1700 were not entirely to their advantage. None of them was allowed to own retail shops or stalls unless they had already had them in 1690. With that practiced eye for financial advantage characteristic of German princes, whether Habsburgs, Hohenzollerns, Wittelsbachs or whoever they were, in dealing with Jews, Frederick increased their annual protection money to 2,000 ducats. No one could contract a marriage without first disbursing a gold gulden. In exchange they were permitted to maintain three houses of worship, one for the Liebmannin and her followers, one for the almost as powerful Koppel Riess, and a third for the rest of the community.

This last ordinance immediately set the Jews at loggerheads. Those who had arrived only decades ago from Vienna and those who had long been resident in the north of Germany had no wish to worship their God together. A certain Markus Magnus, servant and favorite of the Crown Prince, tried to edge the Liebmannin out of her privileged position. In the course of time the greatest disturbance and confusion prevailed in the community, and in the end Magnus and the widow took each other to court. The headstrong adversaries came up before a commission which included the privy councilor for finance Freiherr von Bartholdi, the Liebmannin took refuge behind the King, who proceeded to undermine the conciliatory work of the commission, which was already achieving some success — in short, the building of the Berlin temple was accompanied by a storm of complaints and intrigue, until at last the irritable Jews were mollified and in 1712 the foundation stone was laid.

A further, worse affliction, which likewise was contrived by one of their own number, remained to be suffered by the Jews of the electorate in Frederick’s reign. With zealous servility, their former fellow-believer Franz Wentzel, who had been baptized, drew the authorities’ attention to the fact that a passage in the Hebrew prayer Aleinu insulted the person of the Savior in the most scandalous fashion. For in this prayer, which was uttered twice a day and as many as three times on the Sabbath, “the Jews conducted themselves blasphemously” at the words “we kneel and bow, but not before the hanged Jesus,” when they spat “as if at an abomination” and jumped slightly away from the spot where they stood. “This blasphemy,” explained Wentzel, “is not printed in any prayer-book, but a space is left for it and it is constantly drummed into the impressionable children and learnt by heart by them.”

Since the medieval accusations of desecration of the Host and ritual murder, no complaint as grave as this had been made against Jews. Urged on by his ecclesiastics, the King gave orders for the most exact and searching inquiry; the elders of all the Jewish communities in Brandenburg were summoned to Küstrin and each of them, under severe and individual cross-examination, was directed to give his interpretation of the prayer Aleinu. Some said that they did utter this prayer, but not the words in question. Others translated “Hevel verick,” which according to Wentzel referred to “the hanged Jesus,” as meaning fools, heathens or idolaters. A third group pointed out that the prayer Aleinu was composed by the prophet Joshua, and therefore before the appearance of the Christians’ Messiah. Since their ancestors had been accustomed 3,000 years ago to spit at a certain point in the prayer, they did the same, but “they spat not in mockery of any person.”

The only way out of this confusion appeared to be to constrain the Jews, in swearing the dreadful oath imposed upon them of old, to abjure any evil intention expressed by this prayer. This they were prepared to do. But the King, perhaps following the whispered suggestion of the Liebmannin, but more likely his own judgment, enacted a decree with the regal solicitude which that good and shrewd sovereign, a follower of Leibniz’s doctrine, bestowed upon even the most despised of his subjects. In this decree he banned the use of the words “Hevel verick,” the spitting and jumping away from the spot, but at the same time freed them from the painful necessity of the oath:

When we gaze with merciful eyes upon the poor Jewish people, that our God has made subject to us in our lands, we do wish right heartily that this people, that the Lord loved so greatly of old, and did choose for his own from all other peoples, should at last be freed from their blindness, and be brought into a communion with us in our faith in the Messiah and Savior of the world, born of their own line: Whereas however the great work of conversion belongs to the spiritual kingdom of Christ, and our temporal power has no place in it, and we yield up all power over the conscience of mankind to the Lord of all Lords; therefore we must await the time and the hour which our merciful God has chosen to enlighten them, according only to His own gracious will, suffering them meanwhile with patience, and using means towards their conversion with love and gentleness; … while yet we deem ourselves most dutifully bound to resist and mightily to oppose the evil of their rising up against Christ Jesus, our Lord and Savior, and His Kingdom.

The questionable practices of the prayer Aleinu were now forbidden to them “from now until time eternal,” but no intention to offend was associated with this ban:

Yet we are graciously pleased to expect that the Jews will show the most submissive obedience to this our decree, which we have devised in the most gracious consideration that they were once the people beloved of God, and are the friends of our Savior in the flesh, with love, pity and mercy towards them … since therein is nothing in the smallest degree contrary to their religion, ceremonies, precepts or customs … They who are now willing to follow obediently our most gracious and most earnest desire may, like other loyal subjects, enjoy our sovereign protection and safeguard.

These were the words of a Prussian king in “Cölln an der Spree” in 1703, when no one in any other corner of the German states wished to be reminded of the “fleshly friendship” of the wretched Jews with the Savior. It was the first sign of benevolent intentions towards the Jews since the days of their great, gracious and just protector Charles V. It was the flaring up of a humane sympathy which was to find an echo in Frederick I’s great-grandchildren, but also in both learned and simple men of his nation before the century came to an end.

His son, however, opposed to his father’s attitude for the reasons already mentioned, dealt differently with this matter, according to his own judgment. He had no love, nor even consideration for this foreign community which had failed to integrate with its hosts whether from lack of goodwill or simple reluctance. But at first he showed himself, as was his nature, in most cases as just as he was stern. To be sure, the Liebmannin, whose beauty had vanished with age, and through her quarrelsome presumption, was forbidden access to court once he had ascended the throne, put under a ten-month-long house arrest and denied under pain of heavy penalties any claim to the estate of the late King, who had been in her debt to the tune of some 100,000 thalers. After this severe treatment she was again admitted to the very highest protection, but she died, bowed down by grief, a year after the death of Frederick I. Before her death she asked that her royal friend’s most beautiful gift, a gold necklace, should be buried with her. Markus Magnus, who had inveighed against her on behalf of the Crown Prince, was now also removed by the King from his presence.

With the sense of justice which was characteristic of the “soldier-King” and which he manifested everywhere, in his new regulations concerning the Jews he annulled the heavy restrictions which had been placed on them since 1671. Nor did he have any objection to being well rewarded for these mitigations. Eight thousand thalers — perhaps as much as 28,000, if other accounts are to be trusted — were the price for rescinding his father’s decrees of 1700 and abolishing the yellow patch which the Jews had had to wear throughout the Middle Ages as a mark of Cain. In addition, the Jews’ existing conditions were improved, as for example by a new law by which the children of privileged persons were allowed to remain in the country after certain statutory payments had been made, and a widow’s right to protection could be passed on to a second husband.

The reign of Frederick William I thus began more favorably than one might have assumed from his early bitterness “against anything which appeared Liebmännisch.” It would have remained equally benevolent, if in 1721 he had not been roused to the greatest fury by the Jews. The Münzjude (Jewish mint-master) Veit had died with an outstanding debt of more than 100,000 thalers. However rich he had been in his lifetime, his fortune was not to be found after his death, and no one admitted to knowing what had become of it. Veit, known in all his dealings as an honest man, had certainly departed this life at a moment as convenient for his debtors as it was inconvenient for his creditors. But the King refused to believe that no ready cash was available, persisted in his opinion that the whole Jewish community was concealing its whereabouts, and decided overnight to outlaw them. This he did on 15 August, in the presence of the chief court minister Jablonsky, having had every one of them driven into their temple.

A year later the father of our bride was born.

While the traveling carriage — its occupants having been inspected and deemed worthy to pass within the walls of Vienna — drove up the steep Rotenthurmstrasse, past the cathedral of St Stephen and along the Graben, the lady from Berlin may have recalled with some melancholy the wide avenues and prospects of her native city. Here the houses stood in untidy rows, narrow-chested and poky, crowding around the cathedral like unruly sheep around their shepherd, allowing no glimpse of courtyards, gardens, fountains or patches of blue sky. Only a little later, her compatriot Friedrich Nicolai was to find fault with these “narrow, crooked, uneven alleys” in blunter terms than the young woman dared to utter that day: “Handsome squares there are few, and none of the monuments on these has a fine appearance. Thus the city of Vienna itself for the most part makes no very remarkable impression.” As for the Pestsäule (plague memorial column) on the Graben, upon which from now on her eye would fall every morning, Nicolai found it “hideous, a monstrous hotchpotch of unconnected things. No connoisseur of art, accustomed to the contemplation of simple and noble works of sculpture, can gaze with any pleasure at this mass of ungrouped figures piled ineffectually on top of one another.” At home, in his opinion, far better taste was shown in these matters.

Not only the worthy Nicolai, a Prussian pedant and puritan, who was so shocked by the passionate baroque of the Pestsäule, placed the great Frederick’s Berlin high above Maria Theresa’s Vienna. The bride’s father, too, born within the dark confines of his community, saw in the exemplary proportions, the military straightness of the streets, the punctiliously rounded towers, geometric squares and rigorously simple façades of his city an assurance that order reigned there — both in its architecture and in the disposition of its King. Gone were the days when the despotism of the ruler showed itself to be as fickle in favor as in disfavor. Gone were the alternating spring-like mildness and April tempests of the capricious sovereign, gone too the pragmatic justice of the soldier-King, which a sudden suspicion could sweep aside.

Awakened by the sharp, bright intellect of the French encyclopédistes, a new intelligence was at work, as rectilinear as its perspectives. No gentle pity for the people whom the Lord had once loved and then rejected, no mystic dream of their conversion through strict discipline, no sentimentality derived from hatred or partiality disturbed the judgment of this King. Whatever he did was dictated by reason. Out of the sand of the Marches a new and mighty city began to emerge. Like his father, Frederick William I, with whom otherwise he had little in common, Frederick the Great clung to the saying: “The fellow has money — let him build!” Where the money came from was of little concern to him, as long as it helped the city to grow and flourish. Like the soldier-King he planned to populate it generously — with Protestants from Salzburg, from Bohemia, wherever they might come from. In this motley community there was a firmly delineated place for the Jews whom he esteemed lightly, but found useful. Since 1572, the Hohenzollerns had tolerated them in their electorate. Within limits, which were as strictly drawn as ever, he answered for their safety.

In the first decade of his reign the only change was that their restrictions were subjected to a thorough and sensible examination. As the source of this, Manitius, the secretary of finance, named “the odium religiosum emanating ex papatu,” which “is the origin of all misfortune and of the spirit of persecution in the world.” This aversion, however, in his opinion was a thing of the past. Nevertheless, in the event the revised general patent of 1750 was not much more benevolent than the previous ones had been. It allowed a slightly increased number of family members; otherwise things stayed much the same. The attitude of the royal aesthete towards the Jews was unaltered; he enclosed them like his parade grounds, fencing them in with restrictions. But his sense of proportion, to which there was much reference in the new patent, directed them to their safe and proper place within these limits.

This place, as in the days of the Great Elector, they owed solely to their usefulness. As military suppliers they were of great service to Frederick, who was embroiled in wars from the first day of his accession. The moment soon came, however, when they were able to demonstrate their usefulness to the highest degree. Shortly before the King invaded Saxony in order to take possession for the third and last time of Silesia, he concluded a coinage contract with the court jeweler, a protected Jew called Veitel Ephraim, by which he transferred to him the coinage of all the currencies in his states. With this Ephraim there began the rise of a small number of families, closely knit by marriage, who some decades later were to exercise a decided influence on the social scene in Berlin. These were the “juifs de Frédéric le Grand,” whose business sense and understanding of finance contributed as much to Prussia’s greatness as did their daughters to a fruitful union of his hereditary nobility with the nobility of intellect and art.

Their rise stemmed from obscure transactions, which often aroused animosity, between the family heads and their ambitious King. It brought them out of overcrowded dwellings where they clung closely together with their abundant children and hangers-on, into splendid palaces, near the throne. Its origins were Frederick’s intense desire to obtain ever greater power and richer landed property for himself and Prussia, no less than the dubious methods of his mint-masters in procuring for him the means to do so. This they did, like so many devoted servants of German princely courts before them, by dint of repeated debasement of the coinage, sometimes of positive counterfeiting.

In the guild of court Jews, which had been set up long since, but attained genuine status only in the eighteenth century, the coiners were always in the most vulnerable position. Since the right of coinage had passed from the Emperor to all, even the most insignificant, of his princes and bishops, the various currencies of the Holy Roman Empire had lost their firm value. Their gold or silver content went up and down unremittingly. The German silver mines, moreover, had become exhausted since the Thirty Years’ War, the princes found themselves obliged to import precious metals from abroad, and this trade was not only problematic because of the annual rise in the price of silver but also fraught with danger, since the law of many states completely prohibited their export.

As usual, the thankless task, to which no self-respecting merchant would subject himself, fell to the Jews in their arduous struggle for social advancement. A number of them carried it out quietly and without reproach, obtaining silver and coining money as their ruler had ordained. But as soon as it occurred to such a ruler to devalue his currency, those who had followed his orders were held up to execration. This was what happened to Veitel Ephraim, whom Frederick the Great, before the Third Silesian War, instructed to exchange the good old coins of the realm for others which he had minted to a lower value than the nominal one, and provided with a deceptive silver sheen.

Von außen schön, von innen schlimm,

Außen Friedrich, innen Ephraim!

[Outwardly good, evil within, / Outside Frederick, inside Ephraim!]

This song was soon heard in the Prussian states, and after the King’s invasion of Saxony had succeeded and his mint-masters brought into circulation new coins of one-third the former value and low silver content, these were contemptuously referred to as “Ephraimites.” Nevertheless these ruses, which emptied the pockets of the little man, were the only way to conduct a war of seven years’ duration against an overwhelmingly powerful coalition without imposing extortionate taxes or incurring tax debts. Moreover, it was the King who went astray, with his money-clippers by his side.

If the rise of the Friderician Jews took place in a twilight of dubious practices, it took place also in an atmosphere of quarreling and calumny, like that which had prevailed in the Berlin community at the time of the Liebmannin and of Markus Magnus. For soon after, when Ephraim had been promoted from a mere supplier of silver to lessee of the coinage, an opposition party came into being whose sole object was to edge him out of his post. In October 1755, this party, consisting of Herz Gompertz, the husband of Ephraim’s sister Clara, a certain Daniel Itzig and his brother-in-law Moses Isaac, managed to get the lease of all six state mints transferred from Ephraim to itself. How this was accomplished is no longer apparent; probably the opposition outbid Ephraim for the lease.

When, however, the Münzjuden began to reproach each other publicly to the effect that they had lowered the value of the coins as well as raising the price of silver too high, the King, under similar pressure to that of his grandfather Frederick I, ordered them not to trouble him with such proceedings. During the war the feuds between the hostile though closely related groups continued. The administration of the coinage wavered between the two parties, while not only the King, but also his general commissioners and superintendents, were adept at playing one party off against the other. It was not till 1758, when Ephraim’s most dangerous opponents, Major-General von Retzow and his own brother-in-law Herz Gompertz, were dead, that he succeeded in forming a consortium with their former partners Moses Isaac and Daniel Itzig, which took over all the King’s coinage commissions.

Daniel Itzig is the man, among all these confused and unedifying machinations, with whom we will now be concerned. When, greatly respected and advanced in years, he passed away a few months before the turn of the century, the controversial beginnings of his career were forgotten. This patriarch, whose name was to adorn the family trees not only of rich businessmen, great artists and eminent scholars, but also of blue-blooded scions of the ancient aristocracy, had won the favor of his King through the most devoted services. That in doing so he did not overlook his own interests is not to be denied. Nevertheless, the way in which he freed himself and his children’s children from the burden of poverty and ignominious birth was, although less romantic, in no way less honorable than that of the robber knights who from the safety of their castles had lain in wait to prey on passing strangers. Above all it took courage — the courage to make unpleasant decisions which must inevitably come up against resistance; the courage to play scapegoat to an ambitious and, as we will see, disloyal employer; the courage to call down on his head the irrational hate of the community; finally, the courage to take upon himself the venomous excesses of the reproach of future generations — for example, of Carlyle, who spoke years later of the “foul swollen creatures” Ephraim and Itzig, “rolling in foul wealth by the ruin of their neighbors,” although in the well-authenticated way of life of the latter at least, there is no evidence of merciless self-interest, but much of his great philanthropic and charitable nature.

Daniel Itzig enjoyed better favor among his more impartial contemporaries than he did with Carlyle. In a “Characterization of Berlin” published in Philadelphia in 1764 his noble “character and irreproachable way of life” were particularly mentioned. On an official occasion Frederick William II referred to his “well-known respectable conduct and selfless behavior.” And the worthy Johann Balthasar König, a contemporary historian, makes the general observation that “the Jews’ behavior was excellent in the conduct of this business,” and that it was to be doubted “that the Christians would have manifested so much delicacy and subtlety if the business had been entrusted to their care.” Yet it was not König’s well-considered account but the intemperate judgment of Carlyle which was considered fit to establish the image of these men in the consciousness of later times — for history is no less fallible and prejudiced than her most malicious chronicler.

He was of tall, noble proportions, of gentle, beautiful physiognomy, had a keen, penetrating, but friendly gaze; altogether a benevolent, captivating being and at the same time one who commanded respect, in a word, he was a very handsome man. His whole bearing, manner and behavior bespoke manly dignity, it was as if he were from the very beginning called to higher things, as if he were created by nature for gentle manners and good taste, in order to be able to move in refined circles.

Such was the glorified picture of Daniel Itzig which survived among his co-religionists. Today one would hesitate to call him a handsome man. The small portrait preserved at a Carinthian castle by one of his descendants shows a paterfamilias of serious but gentle mien, whose pointed nose and reflectively pursed lips manifest that cunning and circumspection with whose help he had risen to become the most powerful man among Prussian Jewry. Only his large, sea-blue eyes express the leaning towards gentle manners and good taste reported by his eulogist. His wife, Mariane, who in the course of a long marriage bore him sixteen children, had the same bright, clear eyes. As we have seen, they were inherited by his daughter, the bride of our story.

Daniel’s origins cannot be pursued very far back, certainly not into the Middle Ages as in the case of so many German Jewish families. We know only that his grandfather Daniel Jafe lived in Grätz, and in 1679 celebrated the birth of a son, Isaac, who later went to Berlin, where he took up horse-trading. This Isaac (or Itzig) Daniel Jafe, who appears in 1714 on the list of tolerated Jews, was from time to time allowed to sell horses to Frederick William I. Apart from his son Daniel, born to him in his forty-fourth year, he had three sons and two daughters, including Bela, who brought her brother into her husband’s coinage business. Daniel Itzig, “from the very beginning called to higher things,” must have shown early promise as a skilled financier, for he was only thirty-two when, with his brother-in-law Moses Isaac and the latter’s associate Herz Gompertz, he took over the lease of the six mints in Berlin, Magdeburg, Cleve, Aurich, Breslau and Königsberg.

His youth was marked by sorrow. At eighteen he lost his father. That he proved a good son and brother to his family — his mother died at an advanced age — is undoubted. Otherwise the manufacturer Benjamin Elias Wulff of Dessau would never have given him his daughter’s hand in marriage, for Daniel was living in modest circumstances when he courted Mariane (or Miriam) in 1748. The Wulffs, on the other hand, were among the most distinguished families of their faith in Germany. Mariane’s greatgrandfather Moses Benjamin Wulff had, in rivalry with Jost Liebmann, served the Great Elector as court supplier, until Liebmann’s intrigues ruined him, drove him out of the Brandenburg Marches and brought him to Anhalt-Dessau.

This Wulff, who was known as the “long Jew” from his impressive stature, was one of the first and most brilliant of the great princely courtiers, and administered the coinage of the Duke of Gotha and Altenberg. A quarrel of long standing with the house of Gotha, however, brought poverty to his heirs, impelling them to seek their fortune anew in the Prussian capital. But in Dessau, at the time when the hunchbacked boy Moses Mendelssohn was growing up there, the esteem in which the Wulff family was held was as high as it had ever been. Daniel’s marriage to Mariane could not but redound to his honor. It was the start of his rise to success in Berlin. He soon became an agent and a few years later a partner to Herz Gompertz, his wife bore him a child every year, and even if the latest regulations permitted only two of his offspring to settle in the city, he lulled himself in the hope that with the favorable passage of time his residence might continue to be granted to him together with all his nearest and dearest.

His first attempts to prove of service to the King did not work out too well. In 1752 Daniel first entered the coinage business, still as a middleman to Gompertz, who was supplying silver for the new mint at Stettin. Current coinage and small denominations were to be minted there, not only for Pomerania, but for the province of Prussia too. The commission was however carried out in defiance of instructions: more small coins than directed were brought into circulation, better coins already in circulation were melted down for re-use and in the end, contrary to the agreement, even the standard of coinage was debased. The King was dissatisfied, reproved the entrepreneurs and their “almost unrestrainable scheming and despicable behavior,” and gave orders to his agent Graumann “rather to conduct dealings with respectable Christian tradespeople.” But his trust in the latter proved misplaced. They either declined Graumann’s request that they should take over deliveries, or they delivered too little and at unacceptably high prices. And so, with the King’s tacit agreement, a year later Graumann went back to his Münzjuden, who knew how to indemnify themselves against the excessively low silver rate imposed upon them. In March 1754, even they were no longer able to take on the burden of the difficult commission with its low profit margin and gave up the business, upon which the Stettin mint finally had to be closed down.

This débâcle with which Daniel Itzig’s first dealings with the King were to end was due not only to the “scheming and despicable behavior” of the coinage entrepreneurs but also to the unrealistic terms imposed upon them. One thing is certain: as soon as he achieved equal rights in his partnership with Gompertz and in later associations, he gave no occasion for complaints, but was in the habit of carrying on his business reliably and enjoyed the highest possible approval. Frederick’s mistrust of him and his partner had been banished when, in 1755, they received from him responsibility for the six Prussian mints.

In the following year the King’s forces invaded Silesia. The war began to consume money: some 170 million thalers before it was brought to a victorious end. Of this sum, 29 million thalers were covered by a brassage (mint charge) of metal suitable for coinage, the greater part of which came into being through the dealings of Gompertz, Itzig, Isaac and, once again, Ephraim. In the course of time the thaler’s nominal value was repeatedly reduced, until it had sunk by one-third. But more and more of this money was needed, and it seemed more and more difficult to get enough gold and silver into the country. The risks and costs incurred by the entrepreneurs were massive, their profit only an eight per cent share of the price of the metal, while all the profit on the coinage went into the war fund. In the end they took so little pleasure in their job that, in 1760, they tried to buy themselves out for 200,000 thalers. But the King refused to release them from their contract.

Frederick’s Münzjuden had become indispensable to him. No longer did he dispute the integrity of their dealings; he did not even hesitate at the end of the war to give his formal approval to the account for the brassage revenue of the past year. It was granted to them in the following words:

Since His Royal Majesty has deigned henceforth to administer his coinage in his own most gracious person, and since the hitherto general suppliers of coinage Ephraim and Sons and Daniel Itzig have presented their accounts, and their deliveries of coin up to this time have been examined and found to be correct: therefore in consideration of this general supplying of coinage hitherto entrusted to them, His Royal Majesty has most graciously granted his complete approval to the aforesaid Ephraim and Sons and Daniel Itzig and excused them from all further claim on this account.

It would certainly have been pleasant to them to see this announcement made public in the newspapers; but when they made this request to the King, he would not allow it. Now that Austria was vanquished and Prussia’s glory had been achieved, he had no interest in drawing attention to the oppressive measures and questionable means which had helped him to this victory. In truth, he had never concealed the fact that he himself was the originator of this first Prussian inflation. But now he wanted his dealings with the Münzjuden to sink into oblivion, and so the token of their loyalty that they demanded from him was denied them. The profit they had made, and the certainty of being permitted to maintain their residence in Berlin with the King’s approval and with all their children, were their only rewards. Perhaps, as a historian later wrote, this in itself was a proof that they had gained their fortune honestly and that their efforts had been genuinely of service to the welfare of Prussia. Be that as it may, they got no more, and had to make the best of it.

Those who had been the most vehement opponents at the beginning of the war were closely united when it ended. While Hohenzollern and Habsburgs strove with each other at Hochkirch, the enemies Itzig and Ephraim were concluding their own separate peace. At the moment when they buried their differences, the last danger that the position at court of one or the other could be destroyed was cleared out of the way. Now they set to work together to do the King’s dirty work. Together they remained as hostages for three days and nights in General Tottleben’s headquarters during the Russian invasion, while other Jews were forced to pay out fees and sweeteners. Together they fulfilled the double and contradictory office of being Frederick’s most obedient servants and scapegoats, while at the same time dignified and respected elders of their community. Their place at the foot of the throne seemed secure for all that. And so it was not by chance, but an intentional and conspicuous symbol, that they now established themselves within view of the royal residence.

Where Daniel Itzig was living in that autumn of 1758, when his partnership with Ephraim came into being, under what roof the eighth of his sixteen children was born on 29 November, is unknown. Whatever landed property he acquired in his life had not yet fallen to his lot. Still in the obscurity of an overpopulated district, somewhere in this rapidly expanding city of Berlin, his fourth daughter came into the world. She was seven years old when the reconstruction of a row of houses in the Burgstrasse had been completed and her father was able to move into his city mansion. As much as was possible for a man of his origins at that time, he had achieved.

Here, by the side of the Spree, whose opposite shore bordered the palace park, under the clear, wide sky of the Marches, in a victorious country, of whose rise every simple citizen felt part — so much the more a man who had contributed greatly to it — here, in steadily improving prosperity, surrounded by a flock of siblings, a little girl was growing up, whose name was Franziska, but who answered to the pet name Vögelchen (Birdie). She had forgotten the terrors of war, which had made only a muted impression on her mind, as she had forgotten the narrow confines of her first home. A kindly mother, beloved older sisters, an abundance of domestic servants, cared for the child and above all spared her the knowledge that the calm peace and security of this house were still doubtful and endangered. Outside those walls her father’s rank and station were no greater than the lowest idler in the Prussian state saw fit to allow him. And if one were looking out for enemies and for those ready to mock or insult, there were as many of these close at hand as there had once been among the Russians and the Austrians.

The little girl was without doubt approaching a moment which would be like the sudden awakening from a pleasant dream. Yet when it came this moment would not bring with it the cruel severity with which it fell upon children of earlier and future generations. In times of tranquility and, indeed, hope, ill-will vanishes and benevolence increases. Thus the signs of a better future were multiplying in that time of Prussia’s youth. Even the members of a despised faith were to be allowed to harvest the fruits of peace. More and more often those who lived by a trade were allowed that “general privilege” that made them equal to Christian merchants. And while the heads of families whose financial acumen had helped Frederick to win his war were now devoting their energies to turning his country from a little agrarian state into a great mercantile power, their women and children were cultivating the arts and social life.

Those among them, however, whose ambitions were directed at the acquisition, not of property and influence, but of knowledge and wisdom, equally found themselves receiving new, previously unattained honors. In June of the year in which the Peace of Hubertusburg had been signed, a dissertation, “On Evidence in the Metaphysical Sciences,” written in German, was honored by the Prussian Academy in open session. Its author, “well enough known here already through his writings, the indigenous Jew Moses Mendelssohn,” received the prize of 50 ducats, while his rival Kant obtained only the so-called “accessit.” Four years later a book was published that was to bring greater and purer fame to him and his kin than all the outward pomp and splendor of their more prosperous fellow-believers. It was Phaedon — a much admired work, the first philosophical piece of writing read by the young Goethe, the spur to Mendelssohn’s friendship with Herder, a passport to the world of German intellect and a monument of transcendental speculation, although it was knocked from its pedestal when Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was published and Fichte, Hegel and Schelling appeared upon the scene.

Meanwhile, little Franziska’s father, a friend and patron of the philosopher, was climbing the ladder of earthly success, with deliberation and a proper sense of his own patriarchal dignity. In the last winter of the war he had acquired his own factory, the ironworks Sorge und Voigtsfelde in the Harz, close to the border of Brunswick. It had been the King’s wish to develop Prussian industry, in order to be less dependent on expensive imports of goods. Daniel Itzig set up three more foundries, and by the year 1765 he had already invested 100,000 thalers in foundry works. When he later sold them to the mining board in exchange for an equally high annuity for his family he had already added to his enterprises an oil-mill, an English leather factory and, together with his father-in-law, a silk factory.

He had, in compliance with Frederick’s wishes, become a manufacturer as well as a coiner and financier. Certainly he still took part in coinage transactions, but above all, since he had been a co-founder of the Royal Bank, he proudly regarded himself as Frederick’s court banker. He seems to have parted company with Ephraim soon after the Peace of Hubertusburg, as can be assumed from a letter addressed to him in the handwriting of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. In this document General von Tauentzien, whose secretary Lessing was, confirmed to Daniel Itzig that Ephraim’s claim against him for certain business shares was unjustified.

In royal favor, as well as in esteem within his own province, Daniel was rapidly beginning to overtake his former rival and later partner. In the same first year of peace he was named chief elder of the Jewish community in Berlin. The following summer he moved into his mansion, designed for him as a two-winged residence, unpretentiously elegant in the symmetry of its simple lines, in contrast to the more splendid Ephraim house nearby. This house in the Burgstrasse soon became a treasure house of the fine arts. For now, having overcome the rigors of his youth, achieved his arduous rise and completed his fortieth year, he found himself able to develop those “gentle manners and good taste” which were written in his face. Now he was truly moving in “refined circles,” not only of his own faith, but also among enlightened Christians.

Nicolai was his guest, and later, full of admiration, described the Itzig mansion with its valuable paintings, including Rubens’ Ganymede, two musicians by Terborch and works by Watteau and Antoine Pesne, its well-constructed prayer-room and its bathroom, a great rarity at the time. There were many links with Lessing, Mendelssohn’s long-standing friend. Whoever came to the Prussian capital and, in addition to the court, the nobility, the artists and scholars also wished to be introduced into Jewish circles, was taken first to Moses Mendelssohn, then to the house of the man who was now known as the Judenfürst, or Jewish Prince. August von Henning, later a Danish councilor of state, wrote in his description of Berlin in 1772 which has survived into our times:

The Jewish colony is considerable; it comprises four hundred families, estimated at two thousand persons. It has the great advantage of enjoying even greater distinction from the fame of its scholars than from the beauty of its ladies. A letter from Reimarus brought me into the house of the famous Mendelssohn. At the mansion of the banker Itzig I often see the learned Friedländer, who is much esteemed in the cultured world. Itzig has sixteen children, of whom some already have situations in their own right, and others are just at the age when beauty begins to unfold. The charm of the daughters’ beauty is heightened by their talents, particularly for music, and by a finely developed intellect.

It was Franziska, at nearly fourteen years old, whose beauty he saw unfolding. The older sisters — the first-born Hanna, Bella, whose grandson was to be Felix Mendelssohn, and the twenty-year-old Blümchen — were all married by this time, and the younger ones were still in the nursery. It later became clear how rich the musical talent of this fourth daughter would prove to be. She and her sisters also took delight in the theater, and it may well be that an event recorded in the memoirs of Henriette Herz took place in their midst. “As early as my ninth year, that is in about 1773,” Henriette told her biographer J. Fürst, “I attended the performance of a tragedy in the house of a Jewish banker. It was Richard III — by what author I cannot remember — and the daughters of the house had taken the female roles. The impression of this, the first dramatic performance I ever saw, was an inextinguishable one.”

It seems an obvious conclusion that she enjoyed the drama by the unknown author — probably, as Fürst assumes, C. S. Weiss, a popular playwright of the time — in the beautiful, large garden in the suburb of Kölln which Daniel Itzig already owned at that time. This park had been extensively remodeled by its owner with the help of the court gardener, Heidert. Now it contained, according to Friedrich Nicolai in his description of Berlin, “apart from hedges, arcades and shady plantations for one’s delight, several thousand fruit-trees of the best varieties. Here also is a garden theater in the open air. Likewise there are various statues by Knöfler of Dresden.”

No trace remains for posterity of the histrionic power with which those young ladies so inextinguishably impressed on the memory of Henriette Herz a Richard III which was not even by Shakespeare. As transitory as the living performance is the testimony of an aesthetic disposition which is often the only creative streak to be found in great merchants! Daniel Itzig, who was perhaps “called to higher things,” who, had he himself been a grandchild and heir, would have aspired to and attained what his own grandchildren and heirs attained, expressed his propensity for beauty, his love of nobility in a garden. This garden, enclosed in a rectangular piece of land, cut off diagonally at the lower edge, between the Köpenicker Strasse and the Schlesisches Tor, whose design and ornamentation were comparable at that time only with those of the castle grounds of Sanssouci, has long ago disappeared from the face of the earth. It lives on only in a sketch in the Nicolai book and in a melancholy account that appeared in the Vossische Zeitung on 3 May 1865, on the occasion of its final destruction.

In this, the rondels and bosquets of the park, which had already become a wilderness, are praised, together with its sculptures and vases on pedestals, its colossal figures, its benches and staircases in the best style of the Friderician age. The statues were from the hands of masters — Cupids, some furnished with the attributes of Greek gods and heroes, some with other emblems; nymphs and satyrs; figures of children; busts of emperors and bejeweled women. “Among the other sculptures,” the description ends, “two fine vases, with winged dragons for handles, are particularly to be mentioned. The sundial should finally be noted, worked by Ring of Berlin, according to the inscription, after the invention of ‘Rab Israel Moses’ in the year 1762, on a copper plate with detailed divisions, and set upon a dainty pedestal.”

The Vossische Zeitung had this to add, over 100 years ago, on the subject of Itzig and his transitory creation:

We held it to be our duty to recall these sculptures once more, before levers and crowbars banish them from the place allotted to them by an art-loving man in the days when Frederick’s sun rose gloriously over our fatherland and the impulse of his creative genius provoked emulation in all spheres. Was it a high official of state, a cavalier of the favored nobility, an important courtier sunning himself in the direct rays of royal grace, whose creation we admire here, endowed with all the splendor, abundance and prodigality in the use of space of the last century? No, this park, this garden, under whose old trees a kind of fairytale magic wafts towards us, all these weathered old mazes, devastated bowling-greens, these pavilions and bowers, between whose stones grass grows in luxuriance, ruined conservatories, almost marshy water-basins, these splendid avenues and salons of trees, these partly shattered and overthrown sculptures covered with moss and lichen — all these were planned and laid out by a man at the very foot of the ladder of citizenship of those days — a Schutzjude [tolerated Jew]. How characteristic of its time, how interesting in the history of our city is this work, a monument to the great King’s spirit that penetrated into all the strata of society, a proof also of the spirit that was stirring among the Jews in the days of Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn and of how it adorned the patrician citizens of the German cities.

It is not only to prove her father’s aesthetic taste but also to cast some light on Franziska’s childhood, of which so little is known, that the park by the Schlesisches Tor has been described in all its particulars. This was the landscape of her childhood, which she later tried lovingly and laboriously to recreate in the Braunhirschengrund near Vienna. Here her feeling for splendor and beauty unfolded, here were the sources of her gaiety and love of life, here she learned, on the stone steps of the “garden theater in the open air,” to move freely and yet with studied grace, here she found pleasure in rich social life, overcame, in her playing and dreaming, the curse of her people, glided, without carrying away any lasting damage, over the moment of recognition of her otherness. Untroubled, even high-spirited, she looked upon the world as would a little princess, without ever doubting that a life among the great and the wise of this earth was to be her lot.

In her crinoline, with powdered hair, distinguished from the children of the Prussian nobility only by certain religious observances and a vague mistrust towards the outside world, the daughter of the Judenfürst walked out into the daylight. After all, had not the King himself bestowed upon her father the highest rank which was to be given in the Jewish hierarchy? On 28 December 1775, Frederick had deigned “to designate Daniel Itzig and Jacob Moses, hitherto the elders of the Jewry of these parts, because of their well-known excellent high reputation and their insight into the condition and the affairs of Jewry, as perpetual chief elders of the Jewish communities of all his several lands, and to confirm them most graciously in this title.” In the same winter, just before Franziska’s seventeenth birthday, Itzig was granted a certificate by the Berlin police authorizing the marriage of his fourth daughter “to the foreign Jew Nathan Adam Arnsteiner” from Vienna.

The wedding took place in the following summer. The Arnsteiners had come to inspect the bride two years earlier: in September 1773 the imperial and royal court administrator Adam Isaac Arnsteiner had requested a passport for himself and his family “for the purpose of traveling to Berlin, where his son wished to marry.” How and why Daniel Itzig chose the young Nathan Adam as his son-in-law is unknown. It is enough to say that both families belonged to that special aristocracy of court Jews, though it was not yet described in those terms, which was as widely ramified as it was tightly knit by intermarriage. Countless links bound one to the other. And if seniority counterbalances even the highest position, Arnsteiner, whose grandfather had served Emperor Joseph I, need not be ashamed to be seen beside the granddaughter of an occasional court supplier to an elector of the German Empire. After all, both houses had emerged from the obscurity of history at about the same time. If the court banker Daniel Itzig was now the most powerful man in Prussian Jewry, the court agent Adam Isaac Arnsteiner was among the most influential Jews of the imperial residence.

On the penultimate day of June 1776 the marriage was solemnized in Berlin, under the richly decorated canopy in the prayer-room of the “Itzig city mansion.” The celebrations in those houses were famous, and not infrequently the nobility pleaded for the privilege of being allowed to attend them. Princess Amelia, the King’s sister, for instance once visited a celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles, where the pretty little Henriette Herz was presented to her. Another sister of the great Frederick, the Queen Mother Ulrica of Sweden, in April 1772 invited herself to a Jewish wedding and was deeply impressed by the splendor and the fine manners which she saw there: “What surprised me the most was the education that the people chosen by God gives its children. I truly believed that I was among persons of high rank and birth.”

Her brother, to whom she wrote thus at Potsdam, had a few malicious remarks to make. “I confess to you, my dear sister,” he replied, “that I would not have expected to find you at a Jewish wedding. You have certainly delighted all the children of the old law by your presence, but I fear greatly that the Hebrew music must have jarred on your ears. The Jews of Berlin are rich and have for some years found it to their taste to give their children a good education, in the hope that God will one day lend his ear again to his people and make them the rulers of the world. I must confess that I see few indications of this, but nothing lifts up one’s soul so much as imagining that we are destined for something higher, and the Jews are filled with this notion.”

The wedding which Queen Ulrica had honored with her presence had taken place in the same year as that of an older Itzig daughter, Blümchen, who had married the “learned Friedländer,” Moses Mendelssohn’s pupil. Certainly, it had not been more splendid and solemn than Franziska’s four years later. Neither one congregation nor the other, however, could delude itself into thinking that God would ever elevate its people to the mastery of the world. Appearances, as Frederick rightly remarked, did not support this view. Indeed, permission for this marriage had been given only on condition that the young couple should leave the country shortly afterwards. Not even the Judenfürst was allowed to keep his daughter and son-in-law in his house for as long as he wished. For even in the land of the great Frederick, who was very well able to appreciate the countless services of his Jewish subjects, there was indignation over every Jew who entered the country, and joy over each one who turned his back on it.

And so, after a last few days in her native city, the bride departed with the young man from Vienna who was almost a stranger to her. The image of the large-roomed, elegant house in the Burgstrasse in Berlin, the image of the patriarchal home, of her kindly parents and beloved siblings, of the garden in which she was safe from the world, with its well-groomed rondels and bosquets, its graceful nymphs and Cupids, accompanied her on her long journey. In the mountains of Saxony, in the forests of Bohemia, she dreamed of birch trees and sand. And when the berline came to a halt on the Graben in Vienna and her husband leaped to the pavement to help her down, as she stood there in silence, while a door opened in a narrow, tall, dark house, her blue eyes still reflected the gleam of the Brandenburg sky.