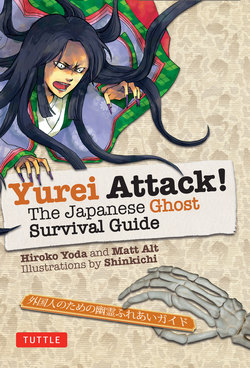

Читать книгу Yurei Attack! - Hiroko Yoda - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSexy & Scary: 03

OTSUYU

Sexy & Scary: 03

OTSUYU

Name in Japanese: お露

Origin: “Botan Doro” (“The Tale of the Peony Lantern”)

Gender: Female

Translation of name: “Morning dew”

Age at death: 16 or 17 (estimated)

Cause of death: Heartbreak

Distinctive features: Superficially, a normal-seeming young woman carrying a peony lantern (see below). Often accompanied by servant, Oyone

Place of interment: Shin-Banzuin Cemetery, Tokyo

Location of haunting: Nezu, Tokyo

Form of Attack: Carnal pleasures

Existence: Believed to be fictional

Threat Level: Medium

Claim to Fame

Next to Oiwa (p.16) and Okiku (p.20) she is one of Japan’s “big three” famous ghosts. But in contrast to Oiwa’s furious retributions, Otsuyu’s tale is one of grave affections.

The Story

The daughter of a hatamoto, a high-ranking samurai in the service of the Shogun, beautiful young Otsuyu’s fate was sealed after a chance introduction to a masterless ronin named Hagiwara Shinzaburo. It was love at first sight for both sides, but a lowly ronin could never ask for the hand of a hatamoto’s daughter in marriage — least of all from Otsuyu’s father, a notoriously stern fellow with a nasty reputation for skewering those who displeased him.

For weeks and months, Shinzaburo begged the neighborhood physician who had introduced the pair to chaperone another visit to Otsuyu; but realizing that the smoldering fire he had inadvertently sparked could well erupt into a conflagration that would consume him as well, the wise but craven doctor hemmed and hawed and made excuses.

Pining for a true love she believed had abandoned her, Otsuyu began to waste away and died, followed shortly thereafter by her heartbroken maidservant Oyone.

Learning of Otsuyu’s untimely death, Shinzaburo’s misery knew no bounds. He inscribed her name on a memorial tablet and placed offerings before it daily. When Obon, the festival of the dead, rolled around that summer, he laid food and lanterns before the tablet as was the custom, and prepared for another night of lamenting love lost.

No sooner than Shinzaburo had lit the lanterns than he heard the clack-clack of wooden geta on the street outside his house. Sliding open a window, he caught sight of a pair of beautiful ladies. The younger of the two, apparently a servant, illuminated the way with a peony lantern. Shinzaburo rubbed his eyes. Could it be? There was no question about it: it was Otsuyu and her maid!

“I thought you were dead!” he cried.

“And I you,” replied Otsuyu in equal astonishment.

Shinzaburo quickly invited the pair into his home, where the trio pieced together how both sides had been deceived to keep them apart. They plotted through the night and separated at daybreak, with a promise that they would soon never part again. For seven nights — always at night — Otsuyu and her maidservant returned to cement their plans.

Shinzaburo’s neighbor, a fortuneteller, overheard the regular midnight chatter and grew suspicious. He peered into Shinzaburo’s home through a crack in the wall. What he saw chilled him to the bone. For Shinzaburo was carrying on an animated conversation with a pair of desiccated corpses, their kimono stained and tattered, their eye sockets gaping holes.

The next day, the fortune-teller confronted Shinzaburo, who reluctantly confessed his plans to elope. But he refused to believe what the fortune-teller told him about Otsuyu’s true form. After much back and forth, the fortune teller convinced Shinzaburo to pay a surprise visit to the neighborhood where Otsuyu claimed to live. Shinzaburo wandered from door to door asking after the pair; but the neighbors claimed no knowledge of any young women living there. On his way home, Shinzaburo took a short cut through the local cemetery at Shin-Banzuin temple, and that is when he spotted them: not the girls, but a pair of fresh grave-markers bearing the names “Otsuyu” and “Oyone.”

Rushing back, the terrified Shinzaburo consulted the abbot of his local temple, who prescribed consecrated ofuda talisman slips to be pasted over his abode’s every opening to keep the spirits at bay. In spite of his feelings for Otsuyu, Shinzaburo knew he had no choice but to oblige. Night after night, he desperately tried to ignore the heartbreaking wails of Otsuyu and Oyone, in turns angry and piteous, issuing from beyond his walls.

Desperate to help her mistress, the ghostly Oyone threatened Shinzaburo’s servants, a married couple who had long served the ronin. With their own fates at stake, the husband and wife bargained with the ghost, demanding 100 ryo — an astounding sum — in return for betraying their master and livelihood.

The rest is history. It isn’t known where or how Oyone obtained the money, but obtain it she did; and Shinzaburo’s treacherous servants peeled just one ofuda from a crack in the wall of their master’s residence.

The next morning, Shinzaburo was found dead in his bedchamber — his face a grimace of terror, and beside him the skeleton of a long-dead woman, its arms thrown around his neck in a final, eternal embrace. At the behest of the abbot with whom he had first consulted, Shinzaburo was buried alongside Otsuyu and Oyone.

The Attack

A product of a more genteel era, The Tale of the Peony Lantern is circumspect as to what precisely occurred within the walls (and more specifically, the bedroom) of Shinzaburo’s mansion, but one can surmise the general details.

Surviving an Encounter

Otsuyu’s fate was inextricably linked to that of her lover; his death effectively released her from her bondage to this Earthly plane. But while you’ll never run into Otsuyu herself, unrequited love is no less powerful a force today than it was in medieval Japan. Should you find yourself in a similar situation, take a page from Otsuyu’s tale and stock up on consecrated ofuda talismans (for convenience, we have included samples on p. 188). Pasting them on doorways, window frames, and over potential entrances is the time-honored method for keeping out all sorts of bogeymen — and women — out of one’s home. You are safe as long as they are in place.

A word of warning for frustrated teens and/or adventurous sorts. Ghost-chronicler Lafcaido Hearn said: “the spirit of the living is positive, the other negative. He whose bride is a ghost cannot live.” (Remember, Shinzaburo did not die with a smile on his face.)

The Literary History

The Tale of the Peony Lantern first appeared in Otogiboko (“A Child’s Amulet”), a 1666 collection of short stories by the Buddhist monk and writer Asai Ryoi, which consisted of adaptations of old Chinese tales reworked for a (then) modern Japanese audience. Although well known, Otsuyu’s story didn’t truly take off until 1884, when it was expanded into a rakugo performance — a form of one-man verbal stage show. This led to an 1892 kabuki version, a performance of which happened to be seen by the one and only Hearn, who retitled the story “A Passional Karma” and included it in his 1899 book In Ghostly Japan.

Trivia Notes

Peony lanterns are an archaic form of illumination once used during the Obon festival. They were so named for the faux peony petals affixed to their tops.

Yoshitoshi’s interpretation of “Botan Doro” from his 36 Ghosts series, showning Otsuyu with Oyone carrying a peony lantern.