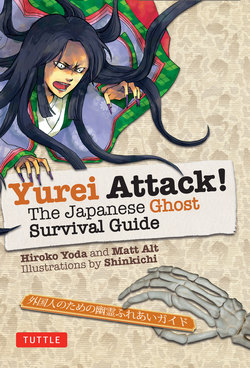

Читать книгу Yurei Attack! - Hiroko Yoda - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFurious Phantoms: 08

SUGAWARA NO MICHIZANE

Furious Phantoms: 08

SUGAWARA NO MICHIZANE

Name in Japanese: 菅原道真

Gender: Male

a.k.a. Sugawara no Michizane; Tenman Daijizai Tenjin (after death); Kan Shojo

Date of Death: March 26, 903

Age at death: 57

Cause of death: Starvation

Type of ghost: Onryo

Distinctive features: Generally speaking, Michizane’s ghost does not physically manifest itself.

Place of interment: Fukuoka, Kyushu

Location of haunting: Heiankyo (Kyoto)

Form of Attack: Causing plagues, droughts, other unpleasantness; Bolts from the blue

Existence: Historical

Threat Level: High

Claim to Fame:

A serious political operator turned angry ghost, hell-bent on avenging his mistreatment at the hands of the Imperial family.

In life, Michizane was a highly intelligent, artistically inclined scholar. (According to one account, he once wrote twenty complete poems on twenty entirely different subjects while eating supper.) Quickly rising through the ranks, he attracted the attention of then- Emperor Uda, giving his career a serious boost. Before long, he had climbed the ladder almost as far as a bureaucrat could climb, attaining influential positions including Udaijin (“Minister of the Right,” essentially a Secretary of State), ambassador to T’ang era China, and Assistant Master of the Crown Prince’s Household, among others. But while his future seemed assured, in reality storm clouds were brewing on the horizon.

The Michizane Incident

The imperial court burned many official records concerning Michizane in an attempt to obscure the connection to his furious spirit. The details of what came many years later to be known as the “Michizane Incident” must necessarily be pieced together from a variety of secondhand accounts.

Overwhelmed by his responsibilities, Uda abdicated the throne in 897, stripping Michizane of his former influence. Far less qualified people from families better connected to the new emperor were promoted, while the talented and loyal Michizane slid into undeserved irrelevance. Demoted, slandered, and accused of crimes he didn’t commit, Michizane was banished to distant Kyushu in 901.

Michizane soldiered on and continued to compose poetry, but had been reduced to abject poverty. He succumbed to malnutrition in the early spring of 903. Upon hearing word of his demise, his rivals must have patted themselves on the back for a job well done. Only Michizane wasn’t done. The attacks began that very year.

The Attacks

A partial list of tatari (attacks) officially attributed to Michizane, by year

903 TORRENTIAL RAINS ALL YEAR LONG

905 DROUGHT

906 FLOODS

907 BAD FLOODS

910 TERRIBLE FLOODS

911 FLOODS OF THE SORT THAT SWALLOW ENTIRE VILLAGES

912 LARGE FIRE IN HEIANKYO

913 DEATH OF MICHIZANE’S RIVAL

914 MORE FIRES IN HEIANKYO

915 OUTBREAK OF CHICKEN POX

918 FLOODS SO HORRIFIC WE HAD BEST NOT SAY ANY MORE

922 WHOOPING COUGH OUTBREAK

923 UNTIMELY DEATH OF EMPEROR’S SON, THE CROWN PRINCE, AT AGE 21

925 UNTIMELY DEATH OF LATE CROWN PRINCE’S INFANT SON

930 BOLT OF LIGHTING FALLS WITHIN PALACE WALLS, KILLING NUMEROUS IMPERIAL OFFICIALS. EMPEROR DAIGO COLLAPSES FROM SHOCK. DIES THREE MONTHS LATER.

Surviving An Encounter

Ever read the Bible? Remember the bit about the plagues Moses’ God brought down upon the Egyptians? Similar thing here. You are in serious trouble. There is nothing the average individual can do to stem the mayhem, other than packing their bags and leaving town at the first hint of bad weather or outbreak of illness. Not exactly a realistic option.

If you happen to be the Emperor of Japan, on the other hand, it’s another story. Appeasing a spirit of this magnitude requires major — almost infrastructural — measures. In this particular case, defusing the spirit’s fury required the Imperial court not only to posthumously reinstate Michizane’s former titles, but to underwrite the construction of an opulent memorial to his memory: the Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine.

Note that this wasn’t an exorcism — Michizane was far too powerful for that; remember the lightning bolts crashing down inside the palace walls? Rather, it was an extravagant show of respect, the closest thing to an official apology the Imperial court could muster. The successful effort formed the cornerstone of what could be called “onryo appeasement strategy” for centuries thereafter: venerating those the Emperor had wronged by elevating them to the status of gods.

Today, Michizane is better known as Tenjin, the Shinto deity of scholarship. So forget about surviving — a modern-day encounter with Michizane is all about passing. Passing your big test, that is. Millions visit his shrine annually for a leg up on their examinations. So stop worrying about ghost attacks and crack those books! Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine is located just 30 minutes from the city of Fukuoka by train; the nearest station is “Nishitetsu Dazaifu.”

Know Your Onryo

Precocious young Michizane at age 11, composing a poem with brush and ink. Print by Yoshitoshi.

Michizane is the archetypical onryo in the most precise definition of the term. While the word is bandied about today to refer to all sorts of angry ghosts, originally and most correctly onryo applies only to those spirits bent on vengeance against the Imperial family.

Michizane’s spirit reacts triumphantly to his belated recognition by the Imperial Court. By Yoshitoshi.

We aren’t exaggerating or overstating the case when we say that the Imperial government took the haunting seriously. A historical text from 1292 called Gukansho shows that the affair still remained a hot topic more than three centuries later. The thirteenth-century author theorizes that the gods orchestrated Michizane’s posthumous reappearance as an example of the repercussions of false accusations, which can give an otherwise good man the necessary credentials, so to speak, to come back as an angry ghost.

Another sign of official respect: Michizane’s face appeared on the 5-yen bill, which went out of circulation in 1929.