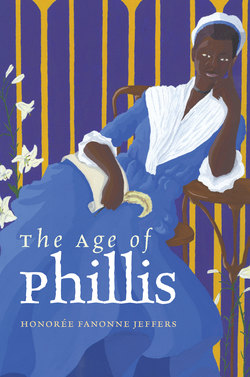

Читать книгу The Age of Phillis - Honorée Fanonne Jeffers - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBook: After

TO BE SOLD

A parcel of likely Negroes imported from Africa,

Cheap for Cash, or Credit with Interest; enquire

of John Avery at his House, next Door to the white

Horse, or at the Store adjoining to said Avery’s Distill

House, at the South End, near the South Market:—Also

if any Persons have any Negroe Men, strong and hearty,

tho’ not of the best moral Character, which are proper

Subjects for Transportation, may have an Exchange

for small Negroes.

— Boston-Gazette and Country Journal, August 3, 1761

Father of mercy, ’twas thy gracious hand

Brought me in safety from those dark abodes.

— Phillis Wheatley, from “To the University of Cambridge, in New-England”

Nine years kept secret in the dark abode,

Secure I lay, conceal’d from man and God:

Deep in a cavern’d rock my days were led;

The rushing ocean murmur’d o’er my head.

— from Homer’s The Iliad, translated by Alexander Pope

MOTHERING #2

Susannah Wheatley, Boston Harbor, Summer 1761

And so,

because the little girl was bony and frail,

Mistress Wheatley gained her for a trifling,

passing by the other slaves from the brig called Phillis.

The white woman’s mind muddled

by what the light revealed: a seven-year-old,

naked, dark body, there for every sailor

to lay his shameless eyes upon,

a child the age of her dead little girl—

I’m trying to both see and discard that day,

as when I stood over the open casket

of an old man, counting the lines on his face,

grieving yet perverse, refusing to believe that hours

from then, he’d be cranked down into the grave—

and so,

the lady tarried in front of the sickly child,

distracted by the gulls screaming at port,

their shadows dogging the constant sea.

They were drawn by the stink of a slave ship,

by lice in unwashed heads of hair,

and so,

she bought that child,

not someone older with muscles—

strong enough to carry a servant’s burden.

That was the moment, a humming, epic page.

That one—

in the carriage, a mothering

gesture, finger beneath a chin,

lifting the face up to trust.

The fickle air between them almost love.

She took the child into her home,

fed and bathed her, deciphered

the naps on her head.

Dressed her in strange garments:

gratitude and slavery.

And so.

FATHERING #2

John Wheatley, Boston Harbor, Summer 1761

Or was it the husband who purchased

the little girl? I’ve thought on this for many

years: how might a wife, a respectable,

white lady, go down to the docks

and complete a fleshy transaction?

What insults might the sailors slide

through her bonnet and modest dress?

She was a mother already.

The still-living twins, Nathaniel

and Mary, salted honey in her older change.

But three earlier children had died:

John (the younger), Susannah (another),

Sarah (gone at the same age as this skinny, dark one)—

their father thought the child might sneak

away his wife’s lingering blues.

Was he tender, touching a sparrowed shoulder?

I mean you no harm, child. I give you my vow.

There is a good meal waiting for us at home.

Or was he gruff with a disembarked stranger

as she halted through language she might

have learned on the ship?

And did the child flinch, a foundling

arrived in an altered world?

Too wise when she tasted

the last of verdancy—

understanding that she was naked,

that heroes strip leaves from the trees

they own?

DESK OF MARY WHEATLEY, WHERE SHE MIGHT HAVE TAUGHT THE CHILD (RE)NAMED PHILLIS TO READ

c. Winter 1763

The dark wood no match

for the gorgeous ebony

of the child who leans against it,

while a taller girl teaches

her artful curves and symbols,

the power of letters arranged in a row.

Easy, the ABCs, then short words,

but counting is different.

In Phillis’s home, the Wolof

number in groups of five, but

only possessions or livestock.

It is a bad luck proposition

to count your offspring: you might

as well prepare their funeral winding—

but facile, the learning of English.

The sound of it, then reading.

When Mary marries the Reverend,

this desk will go with her,

but that is for later.

In this room, she’s a maiden,

covered by the name of her father

who is away trading in dry

goods and one or two slaves.

The mother sits in a cushioned

chair, looking up from her sewing

at the two girls,

the oldest pointing at the page,

the baby rounding her mouth.

There is compassion in dust and sun.

If Susannah tilts her head,

she can deceive herself

that another daughter

is quick from the grave,

that Sarah is the girl who laughs.

Anyone can rise from the dead,

for isn’t Phillis here and breathing,

and wasn’t her ship a coffin?

LOST LETTER #1: PHILLIS WHEATLEY, BOSTON, TO SUSANNAH WHEATLEY, BOSTON

January 18, 1764

Dear Mistress:

Odysseus sailed the ocean like me

and Nymphs held him in their arms.

They are ladies like my yaay.

[i will burn this letter in the hearth you are

watching me as i smile i am a good girl i am]

I shall practice my lessons for you

and Miss Mary, pretend Master Nathaniel

does not yank my hair and tell me,

he’ll take a razor and shave me bald.

For you, God will scrub my skin—

but when might I see my yaay? I cannot

recall how she would say bird or baby

or potato in that other place.

Yaay needs to see that my teeth grew in,

that I am alive after my long journey.

[yaay come for me please i shall be a good

girl i have forgotten how to be naughty]

Today snow comes down. Outside,

a soul has slipped and fallen on the ice.

That’s what that crying means.

Your servant and child,

Phillis

PHILLIS WHEATLEY PERUSES VOLUMES OF THE CLASSICS BELONGING TO HER NEIGHBOR, THE REVEREND MATHER BYLES

c. 1765

I hope that the days Phillis walked

across the street or around the corner

to explore the reverend’s library,

she was escorted by Mary or Susannah.

We know she was brilliant, this child.

Also: biddable, quiet, no wild tendencies—

a surprise to the learned man,

as she refused to surrender

the ring through her nose—

so strange—

and he had other expectations

of her Nation, based upon his studies

of the early (translated)

accounts of her continent, written

by Arabs, Portuguese, and later,

investors of the Royal African Company.

The reverend might

have quizzed the child on the philosopher

Terence, born in Tunisia, who put

aside alien surprise.

Motes suspended in the room,

specks of Homer’s stories—

as rendered by the (cranky) Pope—

how Odysseus, reckless,

bobbed around the world.

His sailors, the equally silly crew,

trapped by his urging words

(but not shackles) accompanied him—

if alone with the Reverend,

I hope there was no danger

for Phillis in his house, that

he and she sat with decent

space between them.

That he didn’t settle her on his lap.

That she didn’t want to—

but couldn’t—

slap at his searching fingers.

I hope he was a gentleman.

Book in hand.

Absent, scholar’s gaze.

LOST LETTER #2: PHILLIS WHEATLEY, BOSTON, TO SAMSON OCCOM, LONDON

March 10, 1766

Dear Most Reverend Sir:

In the name of our Benevolent Savior

Jesus Christ, I bring you tall greetings.

I have never sat with an Indian before.

[i write as i am instructed the white

lady’s hand patting my shoulder]

My mistress says your people are savages,

that I should pray for your tarnished souls.

She says that once I was a savage, too.

[i hurt for my yaay and baay and oh

the mornings of ablutions and millet]

Mistress says that beasts in my homeland

might have devoured me, before God’s mercy—

I enclose my unworthy verse,

and I pray for your heathen brethren.

Prayer makes my mistress very happy.

[the white lady tells me i am lucky

i was saved from my parents

who prayed to carvings and beads

she says my yaay and baay are pagans

though i am allowed to keep loving them

do you pray for your playmates are they yet

alive i do not know where mine were taken

on that day i am reminded to forget]

Your humble servant,

Phillis

LOST LETTER #3: SAMSON OCCOM, LONDON, TO PHILLIS WHEATLEY, BOSTON

August 24, 1766

Dear Little Miss Phillis:

I was happy to receive the kind

favors of your letter and poem,

across this wide water that God created.

[child you are no more savage than me

and what i am is a hungry prayer]

I teach my young ones from Exodus,

that God can be an angry man

and vengeful to the disobedient.

[i teach them to hunt and fish in case renewed

times come i teach them to carve upon

the birch the stories of our ancient line

one of my daughters is near your age i worry

about her she knows the words to our people’s

songs longs to sing in the day but her mother

and i stay her tongue we do not wish danger]

Remember that strict submission

is the watchword of any Christian girl.

Stay mild and consider your masters’ rules.

An Unworthy Servant of Christ,

Samson Occom

SUSANNAH WHEATLEY TENDS TO PHILLIS IN HER ASTHMATIC SUFFERING

Boston, January 1767

When you own a child,

can you treat her the same?

I don’t mean when you birth her,

when you share a well of blood.—

This is a complicated space.

There is slavery here.

There is maternity here.

There is a high and a low

that will last centuries.

Every speck floating in this room

must be considered.

I don’t want to simplify

what is breathing—

choking—

in this room, though there are those

of you who will demand that I do.

Either way I choose, I’m going

to lose somebody.

I want to be human,

to assume that because Susannah

had three offspring who died as children—

the details gone

about coughs that clattered

on, rashes that scattered across

necks or chests,

air that did not expel,

never exhaled to cool tongues—

that Susannah would be desperate

to cling to a new little girl.

Her need to care, her fear,

would rise into Psalms.

When Phillis’s face

was not her mirror,

would that have mattered?

When water did not drench

Phillis’s hair, but lifted it high

into kinks,

would that have mattered?

Can I transcribe the desire

of a womb to fill again?

That a daughter was stolen

from an African woman and given

into a white woman’s hands?

And did Susannah promise the waft

of that grieving mother’s spirit

that she would keep this daughter safe

yet enslaved—

and this

is the craggiest

hill I’ve ever climbed.

THE MISTRESS ATTEMPTS TO INSTRUCT HER SLAVE IN THE WRITING OF A POEM

c. 1769

Note 1. This Verse to the End is the Work of another Hand.

— Addition by Phillis Wheatley at the bottom of “Niobe in Distress …”

| phillisthese are my poemswrites my wordssince wood stoppedafric’s fancy’d happy seatof what i owewho kept mefrom my despairHe calls me ethiopnegroes black as cainmay they lead youspeak new greetingsthough sorrows labormy mother calls | [no one else][no one else][i remember][don’t remind me][to the Savior][in dark abodes][a benighted soul][in the afterlife][may heavens rule][to your mother][in your hands][on your quill][daughter] | susannahsaw you on that dockwanted to take youhow thin you werei’m not your motheri have prayedyou nearly diedknew nothing of Godthose devils burnthe chosen redeemedgive your farewellsspeak your prayersaccept salvationis that not enough |

LOST LETTER #4: SAMSON OCCOM, MOHEGAN, TO SUSANNAH WHEATLEY, BOSTON

August 30, 1770

Dear Madam

I bring you longings of our Savior

who makes our lives possible upon

this invaded travail.

[my people scold me for believing wheelock’s lies

that white man who promised to start a school

for the children of my kind he promised

rooms bordered by brick and wood

that he would teach them tricks of english

that man’s a colorless devil like the one

who spoke scripture in the wilderness]

In prayer, Phillis’s path came to me,

as she stands on my heart’s sweet floor.

She is of an age to marry and sail back

to the clouds of her homeland, to bring

the Good News to the heathens.

[it is time for her to marry i have heard

talk from boston that many white men seek

to snatch a negress such as her this is

a dangerous moment she is too glorious

to stay alone i do not wish her destruction]

Why not let one of our African missionaries

take her hand, as God has ordained?—

If you could spare a coin, I would bless you.

Your Good for Nothing Servant,

Samson Occom

LOST LETTER #5: SUSANNAH WHEATLEY, BOSTON, TO SAMSON OCCOM, MOHEGAN

November 7, 1770

Dear Most Reverend Sir

I am glad your wife is clear of illness.

Family is most important, as well I know—

my dark child is dear and dutiful.

Please do not speak of her marriage,

but only affirm my better wisdom.

[you crow so easily of my child going

to africa forever who would look after

her in that black pagan pit]

I have judged that brambles of marriage

should not snag her—and who to marry?

[do not dare talk of this to me again

you drunk painted creature no wonder wheelock

reneged on his promise to give you that school]

What African man would be worthy of her?

What white man could she equal?

She is a child of no Nation but God’s.

Minister,

our friendship means the earth to me:

I would be blessed if your prayers

told you to keep your own counsel.

[you have not nursed that child heard her scream

and worse the nights of wishing for cries when

wheezing stole her before she returned

what man knows of this my husband was asleep

i shall not sacrifice i promised God to keep her safe]

It gladdens me to know you have put strong

drink behind you and re-sown your faith.—

I send you a few coins, as is my Christian duty.

In Him,

Susannah Wheatley

LOST LETTER #6: PHILLIS WHEATLEY, BOSTON, TO MARY WHEATLEY LATHROP, BOSTON

January 30, 1771

Dear Miss Mary:

I know that marriage is a woman’s

tithe, but this house is cold without you.

I know it is not my place to question

these patterns, why letters speak

a language, and then, the muses cry to me.

[i hope you find this letter in your reticule

i miss you already i thought to leave with you

until mistress held me back]

Yet if I could question Our Lord’s Word,

I’d ask, why is marriage a woman’s task?

[i have no sister of my own each time someone

leaves this house even for a short season i think

of that day i was cut from my earth]

Your mother has explained the stain

of Eve, but tells me, as a slave girl,

marriage is not for me, that I should be glad

that particular chain has passed me by—

I should focus on the Lord for my plight.

[what is it like to call a room your own to sit

in the middle and not on a corner stool

do you feel grand does the hand

weighted by your ring

make you free or mastered]

Your Phillis

THE AGE OF PHILLIS

How old was the child when she first laughed

in her master’s kitchen? She shouldn’t have

been eating at the table with the whites,

but Susannah might have flouted custom:

her woman’s heart soft. Tender. Unboiled meat.

When the child was very small, Susannah

might have brought her into the dining room,

sat her on a stool, placed plain crockery

on the child’s lap, engaged with her in English,