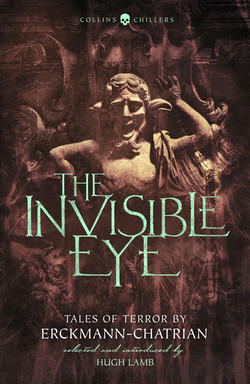

Читать книгу The Invisible Eye: Tales of Terror by Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian - Emile Erckmann, Emile Erckmann, Hugh Lamb - Страница 10

THE BURGOMASTER IN BOTTLE

ОглавлениеI have always professed the highest esteem, and even a sort of veneration for the Rhine’s noble wine; it sparkles like champagne, it warms one like Burgundy, it soothes the throat like Bordeaux, it fires the imagination like the juice of the Spanish grape, it makes us tender and kind like lacryma-christi; and last, but not least, it helps us to dream – it unfolds the extensive fields of fancy before our eyes.

In 1846, towards the end of autumn, I had made up my mind to perform a pilgrimage to Johannisberg. Mounted on a wretched hack, I had arranged two tin flasks along his hollow ribs, and I made the journey by short stages.

What a fine sight a vintage is! One of my flasks was always empty, the other always full; when I quitted one vineyard, there was the prospect of another before me. But it quite troubled me that I had not any one capable of appreciating it to share this enjoyment with me.

Night was closing in one evening; the sun had just disappeared, but one or two stray rays were still lingering among the large vine-leaves. I heard the trot of a horse behind me. I turned a little to the left to allow him to pass me, and to my great surprise I recognised my friend Hippel, who as soon as he saw me uttered a shout of delight.

You are well acquainted with Hippel, his fleshy nose, his mouth especially adapted to the sense of taste, and his rotund stomach. He looked like old Silenus in the pursuit of Bacchus. We shook hands heartily.

The aim of Hippel’s journey was the same as mine; in his quality of first-rate connoisseur he wanted to confirm his opinion as to the peculiarities of certain growths about which he still entertained some doubts.

So we continued our route together. Hippel was extremely gay; he traced out our route among the Rhingau vineyards. We halted occasionally to devote our attention to our flasks, and to listen to the silence which reigned around us.

The night was far advanced when we reached a little inn perched on the side of a hill. We dismounted. Hippel peeped through a small window nearly level with the ground. A lamp was burning on a table, and by it sat an old woman fast asleep.

‘Hallo!’ cried my comrade; ‘open the door, mother.’

The old woman started, got up and came to the window, and pressed her shrunken face against the panes. You would have taken it for one of those old Flemish portraits in which ochre and bistre predominate.

As soon as the old sybil could distinguish us she made a grimace intended for a smile, and opened the door for us.

‘Come in, gentlemen – come in,’ cried she with a tremulous voice; ‘I will go and wake my son; sit down – sit down.’

‘A feed of corn for our horses and a good supper for ourselves,’ cried Hippel.

‘Directly, directly,’ said the old woman assiduously.

She hobbled out of the room, and we could hear her creeping up stairs as steep as a Jacob’s ladder.

We remained for a few minutes in a low smoky room. Hippel hurried to the kitchen, and returned to tell me that he had ascertained there were certain sides of bacon by the chimney.

‘We shall have some supper,’ said he, patting his stomach; ‘yes, we shall get some supper.’

The flooring creaked over our heads, and almost immediately a powerful fellow with nothing but his trousers on, his chest bare, and his hair in disorder, opened the door, took a step or two forward, and then disappeared without saying a word to us.

The old woman lighted the fire, and the butter began to frizzle in the frying-pan.

Supper was brought in; a ham put on the table flanked by two bottles, one of red wine, the other of white.

‘Which do you prefer?’ asked the hostess.

‘We must try them both first,’ replied Hippel, holding his glass to the old woman, who filled it with red.

She then filled mine. We tasted it; it was a strong rough wine. I cannot describe the peculiar flavour it possessed – a mixture of vervain and cypress leaves! I drank a few drops, and my soul became profoundly sad. But Hippel, on the contrary, smacked his lips with an air of satisfaction.

‘Good! very good! Where do you get it from, mother?’ said he.

‘From the hillside close by,’ replied the old woman, with a curious smile.

‘A very good hillside,’ returned Hippel, pouring himself out another glass.

It seemed to me like drinking blood.

‘What are you making such faces for, Ludwig?’ said he. ‘Is there anything the matter with you?’

‘No,’ I answered, ‘but I don’t like such red wine as this.’

‘There is no accounting for tastes,’ observed Hippel, finishing the bottle and knocking on the table.

‘Another bottle of the same,’ cried he, ‘and mind, no mixing, lovely hostess – I am a judge! Morbleu! this wine puts life into me, it is so generous.’

Hippel threw himself back in his chair; his face seemed to undergo a complete transformation. I emptied the bottle of white wine at a draught, and then my heart felt gay again. My friend’s preference for red wine seemed to me ridiculous but excusable.

We continued drinking, I white and he red wine, till one o’clock in the morning.

One in the morning! It is the hour when Fancy best loves to exercise her influence. The caprices of imagination take that opportunity of displaying their transparent dresses embroidered in crystal and blue, like the wings of the beetle and the dragon-fly.

One o’clock! That is the moment when the music of the spheres tickles the sleeper’s ears, and breathes the harmony of the invisible world into his soul. Then the mouse trots about, and the owl flaps her wings, and passes noiselessly over our heads.

‘One o’clock,’ said I to my companion; ‘we must go to bed if we are to set off early tomorrow morning.’

Hippel rose and staggered about.

The old woman showed us into a double-bedded room, and wished us goodnight.

We undressed ourselves; I remained up the last to put the candle out. I was hardly in bed before Hippel was fast asleep; his respiration was like the blowing of a storm. I could not close my eyes, as thousands of strange faces hovered round me. The gnomes, imps, and witches of Walpurgis night executed their cabalistic dances on the ceiling all night. Strange effect of white wine!

I got up, lighted my lamp, and, impelled by curiosity, I went up to Hippel’s bed. His face was red, his mouth half-open, I could see the blood pulsating in his temples, and his lips moved as if he wanted to speak. I stood for some time motionless by his side; I tried to see into the depths of his soul, but sleep is an impenetrable mystery; like death, it keeps its secrets.

Sometimes Hippel’s face wore an expression of terror, then of sadness, then again of melancholy; occasionally his features contracted; he looked as if he was going to cry.

His jolly face, which was made for laughter, wore a strange expression when under the influence of pain.

What might be passing in those depths? I saw a wave now and then mount to the surface, but whence came those frequent shocks? All at once the sleeper rose, his eyelids opened, and I could see nothing but the whites of his eyes; every muscle in his face was trembling, his mouth seemed to try to utter a scream. Then he fell back, and I heard a sob.

‘Hippel! Hippel!’ cried I, and I emptied a jug of water on his head.

This awoke him.

‘Ah!’ cried he, ‘God be thanked, it was but a dream. My dear Ludwig, I thank you for awakening me.’

‘So much the better, and now tell me what you were dreaming about.’

‘Yes, tomorrow; let me sleep now. I am so sleepy.’

‘Hippel, you are ungrateful; you will have forgotten it all by tomorrow.’

‘Morbleu,’ replied he, ‘I am so sleepy, I must go to sleep; leave me now.’

I would not let him off.

‘Hippel, you will have the same dream over again, and this time I shall leave you to your fate.’

These words had the desired effect.

‘The same dream over again!’ cried he, jumping out of bed. ‘Give me my clothes! Saddle my horse! I am off! This is a cursed place. You are right, Ludwig, this is the devil’s own dwelling-place. Let us be off!’

He hurried on his clothes. When he was dressed I stopped him.

‘Hippel,’ said I, ‘why should we hurry away? It is only three o’clock. Let us stay quietly here.’

I opened the window, and the fresh night air penetrated the room, and dissipated all his fears. So he leaned on the window-sill, and told me what follows.

‘We were talking yesterday about the most famous of the Rhingau vineyards. Although I have never been through this part of the country, my mind was no doubt full of impressions regarding it, and the heavy wine we drank gave a sombre tinge to my ideas. What is most extraordinary, in my dream I fancied I was the burgomaster of Welcke’ (a neighbouring village), ‘and I was so identified with this personage, that I can describe him to you as minutely as if I was describing myself. This burgomaster was a man of middle height, and almost as fat as I am. He wore a coat with wide skirts and brass buttons; all down his legs he had another row of small nail-headed buttons. On his bald head was a three-cornered cocked hat – in short, he was a stupidly grave man, drinking nothing but water, thinking of nothing but money, and his only endeavour was to increase his property.

‘As I had taken the outward appearance of the burgomaster, so had I his disposition also. I, Hippel, should have despised myself could I have recognised myself, what a beast of a burgomaster I was. How far better it is to lead a happy life, without caring for the future, than to heap crowns upon crowns and only distil bile! Well, here I am, a burgomaster.

‘When I leave my bed in the morning the first thing which makes me uneasy is to know if the men are already at work among my vines. I eat a crust of bread for breakfast. A crust of bread! what a sordid miser! I who have a cutlet and a bottle of wine every morning! Well, never mind, I take – that is, the burgomaster takes his crust of bread and puts it in his pocket. He tells his old housekeeper to sweep the room and have dinner ready by eleven. Boiled beef and potatoes I think it was – a poor dinner. Well, out he goes.

‘I could describe the road he took, the vines on the hillside, to you exactly,’ continued Hippel; ‘I see them before me now.

‘How is it possible that a man in a dream could conceive such an idea of a landscape? I could see fields, gardens, meadows, and vineyards. I knew this belongs to Pierre, that to Jacques, that to Henri; and then I stopped before one of these bits of ground and said to myself: “Bless me, Jacob’s clover is very fine.” And farther on, “Bless me, again, that acre of vines would suit me wonderfully.” But all the time I felt a sort of giddiness, an indescribable pain in the head. I hurried on, as it was early morning. The sun soon rose, and the heat became oppressive. I was then following a narrow path which crossed through the vines towards the top of the hill. This path led past the ruins of an old castle, and beyond it I could see my four acres of vineyard. I made haste to get there; as I was quite blown when I reached the ruins, I stopped to recover breath, and the blood seemed to ring in my ears, while my heart beat in my breast like a hammer on an anvil. The sun seemed on fire. I tried to go on again, but all at once I felt as if I had received a blow from a club; I rolled under a part of a wall, and I comprehended I had a fit of apoplexy. Then the horror of despair took possession of me. “I am a dead man,” said I to myself; “the money I have amassed with so much trouble, the trees I have so carefully cultivated, the house I have built, all, all are lost – all gone into the hands of my heirs. Now those wretches to whom in my lifetime I refused a kreutzer will become rich at my expense. Traitors! how you will rejoice over my misfortune! You will take the keys from my pockets, you will share my property among yourselves, you will squander my gold; and I – I must be present at this spoilation! What a hideous punishment!”

‘I felt my spirit quit the corpse, but remain standing by it.

‘This spiritual burgomaster noticed that its body had its face blue, and yellow hands.

‘It was very hot, and some large flies came and settled on the face of the corpse. One went up his nose. The body stirred not! The whole face was soon covered with them, and the spirit was in despair because it was impotent to drive them away.

‘There it stood. There, for minutes which seemed hours. Hell was beginning for it already. So an hour went by. The heat increased gradually. Not a breath in the air, nor a cloud in the sky.

‘A goat came out from among the ruins, nibbling the weeds which were growing up through the rubbish. As it passed my poor body it sprang aside, and then came back, opened its eyes with suspicion, smelt about, and then followed its capricious course over the fallen cornice of a turret. A young goatherd came to drive her back again; but when he saw the body he screamed out, and then set off running towards the village with all his might.

‘Another hour passed, slow as eternity. At last a whispering, then steps were heard behind the ruins, and my spirit saw the magistrate coming slowly, slowly along, followed by his clerk and several other persons. I knew every one of them. They uttered an exclamation when they saw me: “It is our burgomaster!”

‘The medical man approached the body, and drove away the flies, which flew swarming away. He looked at it, then raised one of the already stiffened arms, and said with the greatest indifference: “Our burgomaster has succumbed to a fit of apoplexy; he has probably been here all the morning. You had better carry him away and bury him as soon as possible, for this heat accelerates decomposition.”

‘“Upon my word,” said the clerk, “between ourselves, he is no great loss to the parish. He was a miser and an ass, and he knew nothing whatever.”

‘“Yes,” added the magistrate, “and yet he found fault with everything.”

‘“Not very surprising either,” said another, “fools always think themselves clever.”

‘“You must send for several porters,” observed the doctor; “they have a heavy burden to carry; this man always had more belly than brains.”

‘“I shall go and draw up the certificate of death. At what time shall we say it took place?” asked the clerk.

‘“Say about four o’clock this morning.”

‘“The skinflint!” said a peasant, “he was going to watch his workmen to have an excuse for stopping a few sous off their wages on Saturday.”

‘Then folding his arms and looking at the dead body: “Well, burgomaster,” said he, “what does it profit you that you squeezed the poor so hard? Death has cut you down all the same.”

‘“What has he got in his pocket?” asked one.

‘They took out of it my crust of bread.

‘“Here is his breakfast!”

‘They all began to laugh. Chattering as they were the groups prepared to quit the ruins; my poor spirit heard them a few moments, and then by degrees the noise ceased. I remained in solitude and silence. The flies came back by millions.

‘I cannot say how much time elapsed,’ continued Hippel, ‘for in my dreams the minutes seemed endless. However, at last some porters came; they cursed the burgomaster and carried his carcass away; the poor man’s spirit followed them plunged in grief. I went back the same way I came, but this time I saw my body carried before me on a litter. When we reached my house I found many people waiting for me, I recognised male and female cousins to the fourth generation! The bier was set down – they all had a look at me.

‘“It is he, sure enough,” said one.

‘“And dead enough too,” rejoined another.

‘My housekeeper made her appearance; she clasped her hands together and exclaimed: “Such a fat, healthy man! who could have foreseen such an end? It only shows how little we are.”

‘And this was my general oration.

‘I was carried upstairs and laid on a mattress. When one of my cousins took my keys out of my pocket I felt I should like to scream with rage. But, alas! spirits are voiceless; well, my dear Ludwig, I saw them open my bureau, count my money, make an estimate of my property, seal up my papers; I saw my housekeeper quietly taking possession of my best linen, and although death had freed me from all mundane wants, I could not help regretting the sous of which I was robbed.

‘I was undressed, and then a shirt was put on me; I was nailed up in a deal box, and I was, of course, present at my own funeral.

‘When they lowered me into the grave, despair seized upon my spirit; all was lost! Just then, Ludwig, you awoke me, but I still fancy I can hear the earth rattling on my coffin.’

Hippel ceased, and I could see his whole body shiver.

We remained a long time silent, without exchanging a word; a cock crowing warned us that night was nearly over, the stars were growing pale at the approach of day; other cocks’ shrill cry could be heard abroad, challenging from the different farms. A watchdog came out of his kennel to make his morning rounds, then a lark, half awake only, warbled a note or two.

‘Hippel,’ said I to my comrade, ‘it is time to be off if we wish to take advantage of the cool morning.’

‘Very true,’ said he, ‘but before we go I must have a mouthful of something.’

We went downstairs; the landlord was dressing himself; when he had put his blouse on he set before us the relics of our last night’s supper; he filled one of my flasks with white wine, the other with red, saddled our hacks, and wished us a good journey.

We had not ridden more than half a league when my friend Hippel, who was always thirsty, took a draught of the red wine.

‘P-r-r-r!’ cried he, as if he was going to faint, ‘my dream – my last night’s dream!’

He pushed his horse into a trot to escape this vision, which was visibly imprinted in striking characters on his face; I followed him slowly, as my poor Rosinante required some consideration.

The sun rose, a pale pink tinge invaded the gloomy blue of the sky, then the stars lost themselves as the light became brighter. As the first rays of the sun showed themselves, Hippel stopped his horse and waited for me.

‘I cannot tell you,’ said he, ‘what gloomy ideas have taken possession of me. This red wine must have some strange properties; it pleases my palate, but it certainly attacks my brain.’

‘Hippel,’ replied I, ‘it is not to be disputed that certain liquors contain the principles of fancy and even of phantasmagoria. I have seen men from gay become sad, and the reverse; men of sense become silly, and the silly become witty, and all arising from a glass or two of wine in the stomach. It is a profound mystery; what man, then, is senseless enough to deny the bottle’s magic power? Is it not the sceptre of a superior incomprehensible force before which we must be content to bow the head, for we all some time or other submit to its influence, divine or infernal, as the case may be?’

Hippel recognised the force of my arguments and remained silently lost in reverie. We were making our way along a narrow path which winds along the banks of the Queich. We could hear the birds chirping, and the partridge calling as it hid itself under the broad vine-leaves. The landscape was superb, the river murmured as it flowed past little ravines in the banks. Right and left, hillside after hillside came into view, all loaded with abundant fruit. Our route formed an angle with the declivity. All at once my friend Hippel stopped motionless, his mouth wide open, his hands extended in an attitude of stupefied astonishment, then as quick as lightning he turned to fly, when I seized his horse’s bridle.

‘Hippel, what’s the matter? Is Satan in ambuscade on the road, or has Balaam’s angel drawn his sword against you?’

‘Let me go!’ said he, struggling; ‘my dream – my dream!’

‘Be quiet and calm yourself, Hippel; no doubt there are some injurious qualities contained in red wine; swallow some of this; it is a generous juice of the grape which dissipates the gloomy imaginings of a man’s brain.’

He drank it eagerly, and this beneficent liquor re-established his faculties in equilibrium.

He poured the red wine out on the road; it had become as black as ink, and formed great bubbles as it soaked in the ground, and I seemed to hear confused voices groaning and sighing, but so faint that they seemed to escape from some distant country, and which the ear of flesh could hardly hear, but only the fibres of the heart could feel. It was as Abel’s last sigh when his brother felled him to the ground and the earth drank up his blood.

Hippel was too much excited to pay attention to this phenomenon, but I was profoundly struck by it. At the same time I noticed a black bird, about as large as my fist, rise from the bushes near, and fly away with a cry of fear.

‘I feel,’ said Hippel, ‘that the opposing principles are struggling within me, one white and the other black, the principles of good and evil; come on.’

We continued our journey.

‘Ludwig,’ my comrade soon began, ‘such extraordinary things happen in this world that our understandings ought to humiliate themselves in fear and trembling. You know I have never been here before. Well, yesterday I dreamt, and today I see with open eyes the dream of last night rise again before me; look at that landscape – it is the same I beheld when asleep. Here are the ruins of the old château where I was struck down in a fit of apoplexy; this is the path I went along, and there are my four acres of vines. There is not a tree, not a streamlet, not a bush which I cannot recognise as if I had seen them hundreds of times before. When we turn the angle of the road we shall see the village of Welcke at the end of the valley; the second house on the right is the burgomaster’s; it has five windows on the first floor and four below, and the door. On the left of my house – I mean the burgomaster’s – you see a barn and a stable. It is there my cattle are kept. Behind the house is the yard; under a large shed is a two-horse wine-press. So, my dear Ludwig, such as I am you see me resuscitated. The poor burgomaster is looking at you out of my eyes; he speaks to you by my voice, and did I not recollect that before being a burgomaster and a rich sordid proprietor I have been Hippel the bon vivant, I should hesitate to say who I am, for all I see recalls another existence, other habits and other ideas.’

Everything was in accordance with what Hippel had described. We saw the village at some distance down in a fertile valley between hillsides covered with vines, houses scattered along the banks of the river; the second on the right was the burgomaster’s.

And Hippel had a vague recollection of every one we met; some seemed so well known to him that he was on the point of addressing them by name; but the words died away on his lips, and he could not disengage his ideas. Besides, when he noticed the look of indifferent curiosity with which those we met regarded us, Hippel felt he was entirely unknown, and that his face, at all events, sufficed to mask the spirit of the defunct burgomaster.

We dismounted at an inn which my friend assured me was the best in the village; he had known it long by reputation.

A second surprise. The mistress of the inn was a fat gossip, a widow of many years’ standing, and whom the defunct burgomaster had once proposed to make his second wife.

Hippel felt inclined to clasp her in his arms; all his old sympathies awoke in him at once. However, he succeeded in moderating his transports; the real Hippel combated in him the burgomaster’s matrimonial inclinations. So he contented himself with asking her as civilly as possible for a good breakfast and the best wine she had.

While we were at table, a very natural curiosity prompted Hippel to inquire what had passed in the village since his death.

‘Madame,’ said he with a flattering smile, ‘you were doubtless well acquainted with the late burgomaster of Welcke?’

‘Do you mean the one that died in a fit of apoplexy about three years ago?’ said she.

‘The same,’ replied my comrade, looking inquisitively at her.

‘Ah, yes, indeed, I knew him!’ cried the hostess; ‘that old curmudgeon wanted to marry me. If I had known he would have died so soon I would have accepted him. He proposed we should mutually settle all our property on the survivor.’

My dear Hippel was rather disconcerted at this reply; the burgomaster’s amour propre in him was horribly ruffled. He nevertheless continued his questions.

‘So you were not the least bit in love with him, madame?’ he asked.

‘How was it possible to love a man as ugly, dirty, repulsive, and avaricious as he was?’

Hippel got up and walked to the looking-glass to survey himself. After contemplating his fat and rosy cheeks he smiled contentedly, and sat down before a chicken, which he proceeded to carve.

‘After all,’ he said, ‘the burgomaster may have been ugly and dirty; that proves nothing against me.’

‘Are you any relation of his?’ asked the hostess in surprise.

‘I! I never even saw him. I only made the remark some are ugly, some good-looking; and if one happens to have one’s nose in the middle of one’s face, like your burgomaster, it does not prove any likeness to him.’

‘Oh no,’ said the gossip, ‘you have no family resemblance to him whatever.’

‘Moreover,’ my comrade added, ‘I am not by any means a miser, which proves I cannot be your burgomaster. Let us have two more bottles of your best wine.’

The hostess disappeared, and I profited by this opportunity to warn Hippel not to enter upon topics which might betray his incognito.

‘What do you take me for, Ludwig?’ cried he in a rage. ‘You know I am no more the burgomaster than you are, and the proof of it is my papers are perfectly regular.’

He pulled out his passport. The landlady came in.

‘Madame,’ said he, ‘did your burgomaster in any way resemble this description?’

He read out: ‘Forehead, medium height; nose, large; lips, thick; eyes, grey; figure, full; hair, brown.’

‘Very nearly,’ said the dame, ‘except that the burgomaster was bald.’

Hippel ran his hand through his hair, and exclaimed: ‘The burgomaster was bald, and no one dare to say I am bald.’

The hostess thought he was mad, but as he rose and paid the bill she made no further remark.

When we reached the door Hippel turned to me and said abruptly: ‘Let us be off!’

‘One moment, my friend,’ I replied; ‘you must first take me to the cemetery where the burgomaster lies.’

‘No!’ he exclaimed – ‘no, never! do you want to see me in Satan’s clutches? I stand upon my own tombstone! It is against every law in nature. Ludwig, you cannot mean it?’

‘Be calm, Hippel!’ I replied. ‘At this moment you are under the influence of invisible powers; they have enveloped you in meshes so light and transparent that one cannot see them. You must make an effort to burst them; you must release the burgomaster’s spirit, and that can only be accomplished upon his tomb. Would you steal this poor spirit? It would be a flagrant robbery, and I know your scrupulous delicacy too well to suppose you capable of such infamy.’

These unanswerable arguments settled the matter.

‘Well, then, yes,’ said he, ‘I must summon up courage to trample on those remains, a heavy part of which I bear about me. God grant I may not be accused of such a theft! Follow me, Ludwig; I will lead you to the grave.’

He walked on with rapid steps, carrying his hat in his hand, his hair in disorder, waving his arms about, and taking long strides, like some unhappy wretch about to commit a last act of desperation, and exciting himself not to fail in his attempt.

We first passed along several lanes, then crossed the bridge of a mill, the wheel of which was gyrating in a sheet of foam; then we followed a path which crossed a field, and at last we arrived at a high wall behind the village, covered with moss and clematis; it was the cemetery.

In one corner was the ossuary, in the other a cottage surrounded by a small garden.

Hippel rushed into the room; there he found the gravedigger, all along the walls were crowns of immortelles. The gravedigger was carving a cross, and he was so occupied with his work that he got up quite alarmed when Hippel appeared. My comrade fixed his eyes upon him so sternly that he must have been frightened, for during some seconds he remained quite confounded.

‘My good man,’ I began, ‘will you show us the burgomaster’s grave?’

‘No need of that,’ cried Hippel; ‘I know it.’

Without waiting for us he opened the door which led into the cemetery, and set off running like a madman, springing over the graves and exclaiming: ‘There it is; there! Here we are!’

He must evidently have been possessed by an evil spirit, for in his course he threw down a cross crowned with roses – a cross on the grave of a little child!

The gravedigger and I followed him slowly.

The cemetery was large; weeds, thick and dark-green in colour, grew three feet above the soil. Cypresses dragged their long foliage along the ground; but what struck me most at first was a trellis set up against the wall, and covered with a magnificent vine so loaded with fruit that the bunches of grapes were growing one over the other.

As we went along I remarked to the gravedigger; ‘You have a vine there which ought to bring you in something.’

‘Oh, sir,’ he began in a whining tone, ‘that vine does not produce me much. No one will buy my grapes; what comes from the dead returns to the dead.’

I looked the man steadily in the face. He had a false air about him, and a diabolical grin contracted his lips and his cheeks. I did not believe what he said.

We now stood before the burgomaster’s grave. Opposite there was the stem of an enormous vine, looking very like a boa-constrictor. Its roots, no doubt, penetrated to the coffins, and disputed their prey with the worms. Moreover, its grapes were of a red violet colour, while the others were white, very slightly tinged with pink. Hippel leaned against the vine, and seemed calmer.

‘You do not eat these grapes yourself,’ said I to the gravedigger, ‘but you sell them.’

He grew pale, and shook his head in dissent.

‘You sell them at Welcke, and I can tell you the name of the inn where the wine from them is drunk – it is The Fleur de Lis.’

The gravedigger trembled in every limb.

Hippel seized the wretch by the throat, and had it not been for me he would have torn him to pieces.

‘Scoundrel!’ he exclaimed, ‘you have been the cause of my drinking the quintessence of the burgomaster, and I have lost my own personal identity.’

But all on a sudden a bright idea struck him. He turned towards the wall in the attitude of the celebrated Brabançon Männe-Kempis.

‘God be praised!’ said he, as he returned to me, ‘I have restored the burgomaster’s spirit to the earth. I feel enormously relieved.’

An hour later we were on our road again, and my friend Hippel had quite recovered his natural gaiety.