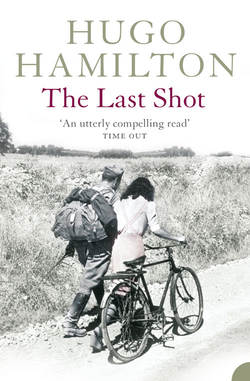

Читать книгу The Last Shot - Hugo Hamilton - Страница 14

10

ОглавлениеAccording to the diaries of Bertha Sommer, an impeccably written account of the life of a young woman who reached the age of twenty when the Second World War started, she was born with a trinity of strong values: faith, honesty and cleanliness. There was nothing Bertha liked more than to wash her feet in the evening. She liked clean feet. Her faith and honesty helped her through what she called ‘the turbulent times’ in which she lived.

Born in the small Rhineland town of Kempen, she was brought up in a family devoted to the Catholic faith, except perhaps for her father, Erich, who was more devoted to cynicism and a good joke. In any case, both cynicism and Catholicism combined to place the family at odds with the new ideology of Nazism, and with the people in their town who had risen to prominence out of nowhere.

Up to then, Bertha’s father had been a prominent businessman with a fine toy and stationery shop on the market square. He had a prodigious disregard for the most elementary notion of profit and loss. He refused to join what he called the ‘Brown Wave’. His standing with the people of the town was based on the old values of gentlemanly wit. ‘God save us from sudden wealth,’ he would say, to the amusement of his followers, who shared his taste for wine, song and humour, along with his compulsion for practical jokes. One Sunday morning he borrowed a brown Nazi cap and climbed up to place it on top of the St George monument at the centre of the market square. Then he went and apologized for offending St George.

But Germany had lost its sense of humour. Nothing could save Erich Sommer from the plummeting Weimar economy, the accelerating age of fascism and his own progressive ill-health. The pulmonary illness which he had brought back from the First World War got the better of him. He bowed out just before the Second World War, leaving behind his wife and five daughters, a trove of unsaleable toys, a hoard of initialled silver cutlery which was eventually sold off for nothing, and his inimitable sense of humour. Bertha writes how he asked her to bring him a mirror on his death-bed, where he looked at himself in silence for a long time before he said: ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Erich.’

With little else to share among them, the five sisters held on to some of their father’s humour. They had a propensity to break down laughing, often until the tears rolled down their faces. His remarks were repeated as a comfort to their mother.

Bertha’s mother, Maria, a professional opera singer who had given up her art for marriage, tried in vain to salvage the business. She resorted to giving singing and piano classes instead. If nothing else, the house was filled with laughter and music. Five girls and a mother who had once sung in the opera. They all sang arias, Schumann, hymns, love songs, pop songs like ‘Lili Marlene’, nursery rhymes – everything. In winter they placed a lighted candle into the grate to give students the illusion of warmth. But the demand for piano lessons had begun to diminish in a country preparing for war. The family eventually came to depend on social security under the new National Socialist state.

Life in Kempen became harder to explain. The Jews in the town disappeared. Families to whom Bertha had often been sent to buy gherkins had gone overnight. Once, on a trip to an aunt in Düsseldorf, Bertha records in her diary how she and her mother saw brand new shoes and leatherwear flung into the streets and how her mother said, ‘What idiots. They’ll regret this some day.’ Shortly after that, the social security payments were mysteriously withdrawn from the Sommer family and life became impossible.

Plans had to be made to ease the burden. Grandmothers and aunts all conferred to make the best decisions for the five girls. Husbands were sought for the two eldest. The two youngest continued at school. Bertha, right in the middle, went to work as a secretarial assistant at the employment exchange, where she went on to obtain excellent references praising her enthusiasm and attractive manner. When the war came, her attributes were welcomed into the service of the army as part of the civilian personnel.

Bertha spent most of the time on the French coast of Normandy until the British arrived. She used the years in France to help her family, regularly sending home money to her mother and regularly arriving home with suitcases full of French fashions – dresses, blouses, hats, lingerie – all of which were quickly claimed by her sisters.

Shortly before D Day, she left France for the last time, with her cases stuffed to the gills. The trains were packed with girls coming home with their belongings, all evacuating back from the Normandy coast. The bombs were already raining on Germany. Bertha prayed hard. When they heard the planes overhead, she prayed for her life. And for her suitcases.