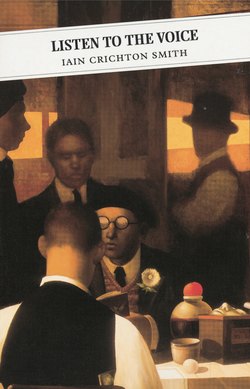

Читать книгу Listen To The Voice - Iain Crichton Smith - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Play

ОглавлениеWHEN HE STARTED teaching first Mark Mason was very enthusiastic, thinking that he could bring to the pupils gifts of the poetry of Wordsworth, Shakespeare and Keats. But it wasn’t going to be like that, at least not with Class 3g. 3g was a class of girls who, before the raising of the school leaving age, were to leave at the end of their fifteenth year. Mark brought them ‘relevant’ poems and novels including Timothy Winters and Jane Eyre but quickly discovered that they had a fixed antipathy to the written word. It was not that they were undisciplined—that is to say they were not actively mischievous—but they were thrawn: he felt that there was a solid wall between himself and them and that no matter how hard he sold them Jane Eyre, by reading chapters of it aloud, and comparing for instance the food in the school refectory that Jane Eyre had to eat with that which they themselves got in their school canteen, they were not interested. Indeed one day when he was walking down one of the aisles between two rows of desks he asked one of the girls, whose name was Lorna and who was pasty-faced and blond, what was the last book she had read, and she replied,

‘Please, sir, I never read any books.’

This answer amazed him for he could not conceive of a world where one never read any books and he was the more determined to introduce them to the activity which had given himself so much pleasure. But the more enthusiastic he became, the more eloquent his words, the more they withdrew into themselves till finally he had to admit that he was completely failing with the class. As he was very conscientious this troubled him, and not even his success with the academic classes compensated for his obvious lack of success with this particular class. He believed in any event that failure with the non-academic classes constituted failure as a teacher. He tried to do creative writing with them first by bringing in reproductions of paintings by Magritte which were intended to awaken in their minds a glimmer of the unexpectedness and strangeness of ordinary things, but they would simply look at them and point out to him their lack of resemblance to reality. He was in despair. His failure began to obsess him so much that he discussed the problem with the Head of Department who happened to be teaching Rasselas to the Sixth Form at the time with what success Mark could not gauge.

‘I suggest you make them do the work,’ said his Head of Department. ‘There comes a point where if you do not impose your personality they will take advantage of you.’

But somehow or another Mark could not impose his personality on them: they had a habit for instance of forcing him to deviate from the text he was studying with them by mentioning something that had appeared in the newspaper.

‘Sir,’ they would say, ‘did you see in the papers that there were two babies born from two wombs in the one woman.’ Mark would flush angrily and say, ‘I don’t see what this has to do with our work,’ but before he knew where he was he was in the middle of an animated discussion which was proceeding all around him about the anatomical significance of this piece of news. The fact was that he did not know how to deal with them: if they had been boys he might have threatened them with the last sanction of the belt, or at least frightened them in some way. But girls were different, one couldn’t belt girls, and certainly he couldn’t frighten this particular lot. They all wanted to be hairdressers: and one wanted to be an engineer having read in a paper that this was now a possible job for girls. He couldn’t find it in his heart to tell her that it was highly unlikely that she could do this without Highers. They fantasized a great deal about jobs and chose ones which were well beyond their scope. It seemed to him that his years in Training College hadn’t prepared him for this varied apathy and animated gossip. Sometimes one or two of them were absent and when he asked where they were was told that they were baby sitting. He dreaded the periods he had to try and teach them in, for as the year passed and autumn darkened into winter he knew that he had not taught them anything and he could not bear it.

He talked to other teachers about them, and the History man shrugged his shoulders and said that he gave them pictures to look at, for instance one showing women at the munitions during the First World War. It became clear to him that their other teachers had written them off since they would be leaving at the end of the session, anyway, and as long as they were quiet they were allowed to talk and now and again glance at the books with which they had been provided.

But Mark, whose first year this was, felt weighed down by his failure and would not admit to it. There must be something he could do with them, the failure was his fault and not theirs. Like a missionary he had come to them bearing gifts, but they refused them, turning away from them with total lack of interest. Keats, Shakespeare, even the ballads, shrivelled in front of his eyes. It was, curiously enough, Mr Morrison who gave him his most helpful advice. Mr Morrison spent most of his time making sure that his register was immaculate, first writing in the O’s in pencil and then rubbing them out and re-writing them in ink. Mark had been told that during the Second World War while Hitler was advancing into France, Africa and Russia he had been insisting that his register was faultlessly kept and the names written in carefully. Morrison understood the importance of this though no one else did.

‘What you have to do with them,’ said Morrison, looking at Mark through his round glasses which were like the twin barrels of a gun, ‘is to find out what they want to do.’

‘But,’ said Mark in astonishment, ‘that would be abdicating responsibility.’

‘That’s right,’ said Morrison equably.

‘If that were carried to its conclusion,’ said Mark, but before he could finish the sentence Morrison said,

‘In teaching nothing ought to be carried to its logical conclusion.’

‘I see,’ said Mark, who didn’t. But at least Morrison had introduced a new idea into his mind which was at the time entirely empty.

‘I see,’ he said again. But he was not yet ready to go as far as Morrison had implied that he should. The following day however he asked the class for the words of ‘Paper Roses’, one of the few pop songs that he had ever heard of. For the first time he saw a glimmer of interest in their eyes, for the first time they were actually using pens. In a short while they had given him the words from memory. Then he took out a book of Burns’ poems and copied on to the board the verses of ‘My Love is Like a Red Red Rose’. He asked them to compare the two poems but found that the wall of apathy had descended again and that it was as impenetrable as before. Not completely daunted, he asked them if they would bring in a record of ‘Paper Roses’, and himself found one of ‘My Love is Like a Red Red Rose’, with Kenneth Mackellar singing it. He played both songs, one after the other, on his own record player. They were happy listening to ‘Paper Roses’ but showed no interest in the other song. The discussion he had planned petered out, except that the following day a small girl with black hair and a pale face brought in a huge pile of records which she requested that he play and which he adamantly refused to do. It occurred to him that the girls simply did not have the ability to handle discussion, that in all cases where discussion was initiated it degenerated rapidly into gossip or vituperation or argument, that the concept of reason was alien to them, that in fact the long line of philosophers beginning with Plato was irrelevant to them. For a long time they brought in records now that they knew he had a record player but he refused to play any of them. Hadn’t he gone far enough by playing ‘Paper Roses’? No, he was damned if he would go the whole hog and surrender completely. And yet, he sensed that somewhere in this area of their interest was what he wanted, that from here he might find the lever which would move their world.

He noticed that their leader was a girl called Tracy, a fairly tall pleasant-looking girl to whom they all seemed to turn for response or rejection. Nor was this girl stupid: nor were any of them stupid. He knew that he must hang on to that, he must not believe that they were stupid. When they did come into the room it was as if they were searching for substance, a food which he could not provide. He began to study Tracy more and more as if she might perhaps give him the solution to his problem, but she did not appear interested enough to do so. Now and again she would hum the words of a song while engaged in combing another girl’s hair, an activity which would satisfy them for hours, and indeed some of the girls had said to him, ‘Tracy has a good voice, sir. She can sing any pop song you like.’ And Tracy had regarded him with the sublime self-confidence of one who indeed could do this. But what use would that be to him? More and more he felt himself, as it were, sliding into their world when what he had wanted was to drag them out of the darkness into his world. That was how he himself had been taught and that was how it should be. And the weeks passed and he had taught them nothing. Their jotters were blank apart from the words of pop songs and certain secret drawings of their own. Yet they were human beings, they were not stupid. That there was no such thing as stupidity was the faith by which he lived. In many ways they were quicker than he was, they found out more swiftly than he did the dates of examinations and holidays. They were quite reconciled to the fact that they would not be able to pass any examinations. They would say,

‘We’re the stupid ones, sir.’ And yet he would not allow them that easy option, the fault was not with them, it was with him. He had seen some of them serving in shops, in restaurants, and they were neatly dressed, good with money and polite. Indeed they seemed to like him, and that made matters worse for he felt that he did not deserve their liking. They are not fed, he quoted to himself from Lycidas, as he watched them at the check-out desks of supermarkets flashing a smile at him, placing the messages in bags much more expertly than he would have done. And indeed he felt that a question was being asked of him but not at all pressingly. At night he would read Shakespeare and think, ‘There are some people to whom all this is closed. There are some who will never shiver as they read the lines

Absent thee from felicity awhile

and in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

to tell my story.

If he had read those lines to them they would have thought that it was Hamlet saying farewell to a girl called Felicity, he thought wryly. He smiled for the first time in weeks. Am I taking this too seriously, he asked himself. They are not taking it seriously. Shakespeare is not necessary for hairdressing. As they endlessly combed each other’s hair he thought of the ballad of Sir Patrick Spens and the line

wi gowd kaims in their hair.

These girls were entirely sensuous, words were closed to them. They would look after babies with tenderness but they were not interested in the alien world of language.

Or was he being a male chauvinist pig? No, he had tried everything he could think of and he had still failed. The fact was that language, the written word, was their enemy, McLuhan was right after all. The day of the record player and television had transformed the secure academic world in which he had been brought up. And yet he did not wish to surrender, to get on with correction while they sat talking quietly to each other, and dreamed of the jobs which were in fact shut against them. School was simply irrelevant to them, they did not even protest, they withdrew from it gently and without fuss. They had looked at education and turned away from it. It was their indifferent gentleness that bothered him more than anything. But they also had the maturity to distinguish between himself and education, which was a large thing to do. They recognized that he had a job to do, that he wasn’t at all unlikeable and was in fact a prisoner like themselves. But they were already perming some woman’s hair in a luxurious shop.

The more he pondered, the more he realized that they were the key to his failure or success in education. If he failed with them then he had failed totally, a permanent mark would be left on his psyche. In some way it was necessary for him to change, but the point was, could he change to the extent that was demanded of him, and in what direction and with what purpose should he change? School for himself had been a discipline and an order but to them this discipline and order had become meaningless.

The words on the blackboard were ghostly and distant as if they belonged to another age, another universe. He recalled what Morrison had said, ‘You must find out what they want to do’, but they themselves did not know what they wanted to do, it was for him to tell them that, and till he told them that they would remain indifferent and apathetic. Sometimes he sensed that they themselves were growing tired of their lives, that they wished to prove themselves but didn’t know how to set about it. They were like lost children, irrelevantly stored in desks, and they only lighted up like street lamps in the evening or when they were working in the shops. He felt that they were the living dead, and he would have given anything to see their eyes become illuminated, become interested, for if he could find the magic formula he knew that they would become enthusiastic, they were not stupid. But how to find the magic key which would release the sleeping beauties from their sleep? He had no idea what it was and felt that in the end if he ever discovered it he would stumble over it and not be led to it by reflection or logic. And that was exactly what happened.

One morning he happened to be late coming into the room and there was Tracy swanning about in front of the class, as if she were wearing a gown, and saying some words to them he guessed in imitation of himself, while at the same time uncannily reproducing his mannerisms, leaning for instance despairingly across his desk, his chin on his hand while at the same time glaring helplessly at the class. It was like seeing himself slightly distorted in water, slightly comic, frustrated and yet angrily determined. When he opened the door there was a quick scurry and the class had arranged themselves, presenting blank dull faces as before. He pretended he had seen nothing, but knew now what he had to do. The solution had come to him as a gift from heaven, from the gods themselves, and the class sensed a new confidence and purposefulness in his voice.

‘Tracy,’ he said, ‘and Lorna.’ He paused. ‘And Helen. I want you to come out here.’

They came out to the floor looking at him uneasily. Ο my wooden O, he said to himself, my draughty echo help me now.

‘Listen,’ he said, ‘I’ve been thinking. It’s quite clear to me that you don’t want to do any writing, so we won’t do any writing. But I’ll tell you what we’re going to do instead. We’re going to act.’

A ripple of noise ran through the class, like the wind on an autumn day, and he saw their faces brightening. The shades of Shakespeare and Sophocles forgive me for what I am to do, he prayed.

‘We are going,’ he said, ‘to do a serial and it’s going to be called “The Rise of a Pop Star”.’ It was as if animation had returned to their blank dull faces, he could see life sparkling in their eyes, he could see interest in the way they turned to look at each other, he could hear it in the stir of movement that enlivened the room.

‘Tracy,’ he said, ‘you will be the pop star. You are coming home from school to your parents’ house. I’m afraid,’ he added, ‘that as in the reverse of the days of Shakespeare the men’s parts will have be to be acted by the girls. Tracy, you have decided to leave home. Your parents of course disapprove. But you want to be a pop star, you have always wanted to be one. They think that that is a ridiculous idea. Lorna, you will be the mother, and Helen, you will be the father.’

He was astonished by the manner in which Tracy took over, by the ingenuity with which she and the other two created the first scene in front of his eyes. The scene grew and became meaningful, all their frustrated enthusiasm was poured into it.

First of all without any prompting Tracy got her school bag and rushed into the house while Lorna, the mother, pretended to be ironing on a desk that was quickly dragged out into the middle of the floor, and Helen the father read the paper, which was his own Manchester Guardian snatched from the top of his desk.

‘Well, that’s it over,’ said Tracy, the future pop star.

‘And what are you thinking of doing with yourself now?’ said the mother, pausing from her ironing.

‘I’m going to be a pop star,’ said Tracy.

‘What’s that you said?’—her father, laying down the paper.

‘That’s what I want to do,’ said Tracy, ‘other people have done it.’

‘What nonsense,’ said the father. ‘I thought you were going in for hairdressing.’

‘I’ve changed my mind,’ said Tracy.

‘You won’t stay in this house if you’re going to be a pop star,’ said the father. ‘I’ll tell you that for free.’

‘I don’t care whether I do or not,’ said Tracy.

‘And how are you going to be a pop star?’ said her mother.

‘I’ll go to London,’ said Tracy.

‘London. And where are you going to get your fare from?’ said the father, mockingly, picking up the paper again.

Mark could see that Tracy was thinking this over: it was a real objection. Where was her fare going to come from? She paused, her mind grappling with the problem.

‘I’ll sell my records,’ she said at last.

Her father burst out laughing. ‘You’re the first one who starts out as a pop star by selling all your records.’ And then in a sudden rage in which Mark could hear echoes of reality he shouted,

‘All right then. Bloody well go then.’

Helen glanced at Mark, but his expression remained benevolent and unchanged.

Tracy, turning at the door, said, ‘Well then, I’m going. And I’m taking the records with me.’ She suddenly seemed very thin and pale and scrawny.

‘Go on then,’ said her father.

‘That’s what I’m doing. I’m going.’ Her mother glanced from daughter to father and then back again but said nothing.

‘I’m going then,’ said Tracy, pretending to go to another room and then taking the phantom records in her arms. The father’s face was fixed and determined and then Tracy looked at the two of them for the last time and left the room. The father and mother were left alone.

‘She’ll come back soon enough,’ said the father but the mother still remained silent. Now and again the father would look at a phantom clock on a phantom mantelpiece but still Tracy did not return. The father pretended to go and lock a door and then said to his wife,

‘I think we’d better go to bed.’

And then Lorna and Helen went back to their seats while Mark thought, this was exactly how dramas began in their bareness and naivety, through which at the same time an innocent genuine feeling coursed or peered as between ragged curtains.

When the bell rang after the first scene was over he found himself thinking about Tracy wandering the streets of London, as if she were a real waif sheltering in transient doss-houses or under bridges dripping with rain. The girls became real to him in their rôles whereas they had not been real before, nor even individualistic behind their wall of apathy. That day in the staff-room he heard about Tracy’s saga and was proud and non-committal.

The next day the story continued. Tracy paced up and down the bare boards of the classroom, now and again stopping to look at ghostly billboards, advertisements. The girls had clearly been considering the next development during the interval they had been away from him, and had decided on the direction of the plot. The next scene was in fact an Attempted Seduction Scene.

Tracy was sitting disconsolately at a desk which he presumed was a table in what he presumed was a café.

‘Hello, Mark,’ she said to the man who came over to sit beside her. At this point Tracy glanced wickedly at the real Mark. The Mark in the play was the dark-haired girl who had asked for the records and whose name was Annie.

‘Hello,’ said Annie. And then, ‘I could get you a spot, you know.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘There’s a night club where they have a singer and she’s sick. I could get you to take her place.’ He put his hands on hers and she quickly withdrew her own.

‘I mean it,’ he said. ‘If you come to my place I can introduce you to the man who owns the night club.’

Tracy searched his face with forlorn longing.

Was this another lie like the many she had experienced before? Should she, shouldn’t she? She looked tired, her shoulders were slumped.

Finally she rose from the table and said, ‘All right then.’ Together they walked about the room in search of his luxurious flat.

They found it. Willing hands dragged another desk out and set the two desks at a slight distance from each other.

The Mark of the play went over to the window-sill on which there was a large bottle which had once contained ink but was now empty. He poured wine into two phantom glasses and brought them over.

‘Where is this man then,’ said Tracy.

‘He won’t be long,’ said Mark.

Tracy accepted the drink and Annie drank as well.

After a while Annie tried to put her hand around Tracy’s waist. Mark the teacher glanced at the class: he thought that at this turn of events they would be convulsed with raucous laughter. But in fact they were staring enraptured at the two, enthralled by their performance. It occurred to him that he would never be as unselfconscious as Annie and Tracy in a million years. Such a shorn abject thing, such dialogue borrowed from television, and yet it was early drama that what he was seeing reminded him of. He had a quick vision of a flag gracing the roof of the ‘theatre’, as if the school now belonged to the early age of Elizabethanism. His poor wooden Ο was in fact echoing with real emotions and real situations, borrowed from the pages of subterraneous pop magazines.

Tracy stood up. ‘I am not that kind of girl,’ she said.

‘What kind of girl?’

‘That kind of girl.’

But Annie was insistent. ‘You’ll not get anything if you don’t play along with me,’ she said, and Mark could have sworn that there was an American tone to her voice.

‘Well, I’m not playing along with you,’ said Tracy. She swayed a little on her feet, almost falling against the blackboard. ‘I’m bloody well not playing along with you,’ she said. ‘And that’s final.’ With a shock of recognition Mark heard her father’s voice behind her own as one might see behind a similar painting the first original strokes.

And then she collapsed on the floor and Annie was bending over her.

‘I didn’t mean it,’ she was saying. ‘I really didn’t mean it. I’m sorry.’

But Tracy lay there motionless and pale. She was like the Lady of Shalott in her boat. The girls in the class were staring at her. Look what they have done to me, Tracy was implying. Will they not be sorry now? There was a profound silence in the room and Mark was aware of the power of drama, even here in this bare classroom with the green peeling walls, the window-pole in the corner like a disused spear. There was nothing here but the hopeless emotion of the young.

Annie raised Tracy to her feet and sat her down in a chair.

‘It’s true,’ he said, ‘it’s true that I know this man.’ He went over to the wall and pretended to dial on a phantom ’phone. And at that moment Tracy turned to the class and winked at them. It was a bold outrageous thing to do, thought Mark, it was as if she was saying, That faint was of course a trick, a feint, that is the sort of thing people like us have to do in order to survive: he thought he was tricking me but all the time I was tricking him. I am alive, fighting, I know exactly what I am doing. All of us are in conspiracy against this Mark. So much, thought Mark, was conveyed by that wink, so much that was essentially dramatic. It was pure instinct of genius.

The stage Mark turned away from the ’phone and said, ‘He says he wants to see you. He’ll give you an audition. His usual girl’s sick. She’s got …’ Annie paused and tried to say ‘laryngitis’, but it came out as not quite right, and it was as if the word poked through the drama like a real error, and Mark thought of the Miracle plays in which ordinary people played Christ and Noah and Abraham with such unconscious style, as if there was no oddity in Abraham being a joiner or a miller.

‘Look, I’ll call you,’ said the stage Mark and the bell rang and the finale was postponed. In the noise and chatter in which desks and chairs were replaced Mark was again aware of the movement of life, and he was happy. Absurdly he began to see them as if for the first time, their faces real and interested, and recognized the paradox that only in the drama had he begun to know them, as if only behind such a protection, a screen, were they willing to reveal themselves. And he began to wonder whether he himself had broken through the persona of the teacher and begun to ‘act’ in the real world. Their faces were more individual, sad or happy, private, extrovert, determined, yet vulnerable. It seemed to him that he had failed to see what Shakespeare was really about, he had taken the wrong road to find him.

‘A babble of green fields,’ he thought with a smile. So that was what it meant, that Wooden O, that resonator of the transient, of the real, beyond all the marble of their books, the white In Memoriams which they could not read.

How extraordinarily curious it all was.

The final part of the play was to take place on the following day.

‘Please sir,’ said Lorna to him, as he was about to leave.

‘What is it?’

But she couldn’t put into words what she wanted to say. And it took him a long time to decipher from her broken language what it was she wanted. She and the other actresses wanted an audience. Of course, why had he not thought of that before? How could he not have realized that an audience was essential? And he promised her that he would find one.

By the next day he had found an audience which was composed of a 3a class which Miss Stewart next door was taking. She grumbled a little about the Interpretation they were missing but eventually agreed. Additional seats were taken into Mark’s room from her room and Miss Stewart sat at the back, her spectacles glittering.

Tracy pretended to knock on a door which was in fact the blackboard and then a voice invited her in. The manager of the night club pointed to a chair which stood on the ‘stage’.

‘What do you want?’

‘I want to sing, sir.’

‘I see. Many girls want to sing. I get girls in here every day. They all want to sing.’

Mark heard titters of laughter from some of the boys in 3a and fixed a ferocious glare on them. They settled down again.

‘But I know I can sing, sir,’ said Tracy. ‘I know I can.’

‘They all say that too.’ His voice suddenly rose, ‘They all bloody well say that.’

Mark saw Miss Stewart sitting straight up in her seat and then glancing at him disapprovingly. Shades of Pygmalion, he thought to himself, smiling. You would expect it from Shaw, inside inverted commas.

‘Give it to them, sock it to them,’ he pleaded silently. The virginal Miss Stewart looked sternly on.

‘Only five minutes then,’ said the night club manager, glancing at his watch. Actually there was no watch on his hand at all. ‘What song do you want to sing?’

Mark saw Lorna pushing a desk out to the floor and sitting in it. This was to be the piano, then. The absence of props bothered him and he wondered whether imagination had first begun among the poor, since they had such few material possessions. Lorna waited, her hands poised above the desk. He heard more sniggerings from the boys and this time he looked so angry that he saw one of them turning a dirty white.

The hands hovered above the desk. Then Tracy began to sing. She chose the song ‘Heartache’.

My heart, dear, is aching;

I’m feeling so blue.

Don’t give me more heartaches,

I’m pleading with you.

It seemed to him that at that moment, as she stood there pale and thin, she was putting all her experience and desires into her song. It was a moment he thought such as it is given to few to experience. She was in fact auditioning before a phantom audience, she and the heroine of the play were the same, she was searching for recognition on the streets of London, in a school. She stood up in her vulnerability, in her purity, on a bare stage where there was no furniture of any value, of any price: on just such a stage had actors and actresses acted many years before, before the full flood of Shakespearean drama. Behind her on the blackboard were written notes about the Tragic Hero, a concept which he had been discussing with the Sixth Year.

‘The hero has a weakness and the plot of the play attacks this specific weakness.’

‘We feel a sense of waste.’

‘And yet triumph.’

Tracy’s voice, youthful and yearning and vulnerable, soared to the cracked ceiling. It was as if her frustrations were released in the song.

Don’t give me more heartaches,

I’m pleading with you.

The voice soared on and then after a long silence the bell rang.

The boys from 3a began to chatter and he thought, ‘You don’t even try. You wouldn’t have the nerve to sing like that, to be so naked.’ But another voice said to him, ‘You’re wrong. They’re the same. It is we who have made them different.’ But were they in fact the same, those who had been reduced to the nakedness, and those others who were the protected ones. He stood there trembling as if visited by a revelation which was only broken when Miss Stewart said,

‘Not quite Old Vic standard.’ And then she was gone with her own superior brood. You stupid bitch, he muttered under his breath, you Observer-Magazine-reading bitch who never liked anything in your life till some critic made it respectable, who wouldn’t recognize a good line of poetry or prose till sanctified by the voice of London, who would never have arrived at Shakespeare on your own till you were given the crutches.

And he knew as he watched her walking, so seemingly self-sufficient, in her black gown across the hall that she was as he had been and would be no longer. He had taken a journey with his class, a pilgrimage across the wooden boards, the poor abject furnitureless room which was like their vision of life, and from that journey he and they had learned in spite of everything. In spite of everything, he shouted in his mind, we have put a flag out there and it is there even during the plague, even if Miss Stewart visits it. It is there in spite of Miss Stewart, in spite of her shelter and her glasses, in spite of her very vulnerable armour, in spite of her, in spite of everything.