Читать книгу Listen To The Voice - Iain Crichton Smith - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

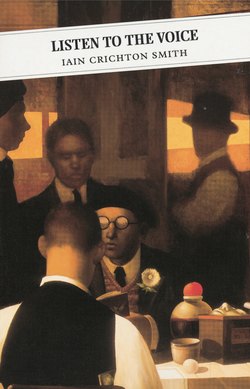

At the Fair

ОглавлениеTHE DAY WAS very hot as had been most of the days of that torrid summer and when they arrived at the park where the fair was being held she found that there was no space for her car: so she had to cruise around the town till she found one, cursing and sweating. It was at times like these, when she felt hot and prickly and obscurely aggressive, that she wished Hugh could drive, but he had tried a few times to do so and he couldn’t and that was that. It wasn’t a big car, it was only a Mini, but even so there didn’t seem to be any space for it anywhere, and policemen were everywhere waving drivers on and sometimes flagging them down to give them information. However after half an hour of circling and back-tracking, she did manage to find a place, a good bit away from the fair, and after she had locked the doors the three of them set off towards it. In the early days, before she had got married, she hadn’t bothered to lock the car at all. Even if a handle fell off a door, like the one for instance that wound down the window, she didn’t bother having it repaired, and the back seat used to be full of old newspapers and magazines which she had bought but never read. Now, however, it was tidy, as Hugh (though, or because, he didn’t drive) kept it so. He also polished it regularly every Sunday, since he didn’t do any writing on Sundays, finding that three hours a day for five days in the week satisfied whatever demon possessed him. She herself worked full-time in an office while he stayed at home writing and making sure that their little daughter who was not yet of school age didn’t burn herself or fall down the stairs or do anything that endangered her welfare.

It was a Saturday afternoon and it was excessively hot, but in spite of the heat Hugh was wearing a jacket and this irritated her. Why couldn’t he be like other men and go about in his shirt sleeves; why must he always wear a jacket even when the sun was at its most glaring, and how could he in fact bear to do so? She herself was wearing a short yellow dress with short sleeves which showed her attractive round arms, and the little girl was wearing a white frilly dress with a locket bouncing at her breast. She looked down at her tanned arms and was surprised to see them so brown since she had been working all summer at her cards in the office catching up with work caused by Margaret’s long absence. But of course at weekends she and her husband and the little girl went out quite a lot. They drove to their own secret glen and sometimes sat and picknicked listening to the noise of the river, which was a deep black, muttering unintelligibly among the stones. The blackness and the noise reminded her for some strange reason of a telephone conversation which had somehow gone wrong, spoiling instead of creating communication. Sometimes they might take a walk up the hill among the stones and the fallen gnarled branches and very rarely they might catch a glimpse at the very top, high above them, of a deer standing questioningly among trees. She loved deer, their elegance and their containment, but her husband didn’t seem to bother much.

The little girl Sheila was taking large steps to keep up with the two of them, now and again taking her mother’s hand and gazing gravely up into her face as if she were silently interrogating her, and then withdrawing her hand quickly and moving away. She talked hardly at all and was very serious and self-possessed. In fact it seemed to her mother that she was more like what she imagined a writer ought to be than Hugh was, for he didn’t seem to notice anything but wandered about absent-mindedly, never listening to anything she was saying and never calling her attention to any interesting sight in the world around him. His silence was profound. She had never seen anyone who paid so little attention to the world: she sometimes thought that if a woman with green hair and a green face walked past him he wouldn’t notice. That surely was not the way a writer ought to be.

Anyway he wasn’t a very successful writer as far as sales went. He had had two small books of poetry published by printing presses no one had ever heard of except himself, and had sold one short story to an equally unknown magazine. She had long ago given up trying to understand his poetry. He himself wavered between thinking that he was a good poet as yet unrecognised and a black despair which made her impatient and often angry with him. In any case the people they lived among didn’t know about writing and certainly couldn’t have cared less about poetry: if you didn’t appear on TV you weren’t quoted. They lived in a council house in a noisy neighbourhood which seemed to have more than the average share of large dogs and small grubby children who stared at you as you went by.

The fair was really immense and she looked down at her small daughter now and again to make sure that she hadn’t got lost. She sometimes worried about her daughter’s silences, thinking that perhaps they were a protection against the two of them.

Hugh said to her, ‘We could spend a lot of money here, do you know that? There are so many things.’

She was suddenly impatient. ‘Well, we only get out once in a while.’ She knew that Hugh worried about money because he himself hardly earned anything, and also because his nature was fundamentally less generous than her own. He had given up working two years before, just to give himself a chance to see if he could succeed as a writer. Before that he had worked in a library, but he complained that working in a library was too much like writing, and in any case he was bored by it and the ignorant people he met. As far as she could see nothing had in fact happened since he gave up writing, for when he wasn’t writing he was reading, and he hardly ever went out. He would sit at his typewriter in the morning but most of the time he didn’t write anything or if he did he threw it in the bucket. When she came home at five she would find the bucket full of small balls of paper. She herself knew very little about literature and couldn’t judge whether such work as he completed was of the slightest value. She sometimes wondered whether she was losing her respect for him: his writing she often thought was a device for avoiding the problems of the real world. On the other hand her own more passionate nature dominated his colder one. Before she met him she had gone out with other men but her resolute self-willed character had led to quarrels of such intensity and fierceness that she knew they would eventually sour any permanent relationship.

As they walked through the fair, pushing their way among crowds of people, they arrived at a stall where one could throw three darts at three different dartboards, and if one got a bull each time would win a prize.

‘Would you like to try this?’ she asked him.

‘Not me. You try it.’

‘All right then,’ she said. ‘I’m going to try it.’ She took the three darts from the rather sour-looking unsmiling woman who looked after the stall and stood steady in front of the board. She was always a little dramatic, wanting to be the centre of attention, though she didn’t realise this herself. She didn’t know about darts, but she would try to get the bulls, for she was very determined and she didn’t see why she couldn’t throw the darts as well as anybody else.

‘Ten pence,’ said the woman handing her the darts with a bored expression.

A number of other people were there, and she smiled at them as if saying, ‘Look at me. I don’t know anything about darts but I’m willing to try. Aren’t I brave?’ She threw the first dart and missed the board altogether. She laughed, and threw the second dart which this time hit the outer rim of the board. She looked proudly round but her husband’s face was turned away, as if he was angry or ashamed of her. She drew back her round pretty tanned arm and threw the dart and it landed quivering in a place near the bull. She turned to him in triumph but he had moved on, little Sheila clutching his hand. There was some scattered ironic applause from the crowd and she bowed to them with a flourish.

When she came up to him, he said, ‘You didn’t do so badly. But these darts are rigged. Some of them don’t stick in the board. All the fairs are the same. They cheat you.’

‘Oh cheer up,’ she said, ‘cheer up. We came here to enjoy ourselves.’

Two youths carrying football scarves in their hands went past and whistled, and Hugh’s face darkened and became stormy and set. She smiled, aware of her slim body in the yellow dress. She hoped that he wouldn’t settle into one of his gloomy childish moods and spoil the day. He looked quite funny really from the back, as he had had a haircut recently: most of the time he wore his hair long like an artist’s or a poet’s but today it was much shorter, showing more clearly the baldish patches at the back.

‘All fairs cheat you,’ he repeated as if he were worried about the amount of money they might spend, as if he were busy adding a sum in his mind. For a poet, she thought, he brooded rather much on money, and far more so than she did. Her philosophy was a simple one: if she had enough for the moment she was quite happy. But today she didn’t care, she actually wanted to spend money, positively and extravagantly, as if by doing so she was making a gesture of hope and joy to the world. As they were passing a machine which emitted cartons of orangeade when money was inserted she bought three and they drank them as they walked along. She threw hers away carelessly on the road, but Hugh and Sheila waited till they came to a bin before depositing theirs.

The heat was really quite intense and she was annoyed that he showed no sign of removing his jacket.

What had she expected from marriage? Was this really what she had expected? Before her marriage she had been lively and alert and carefree but now she wasn’t like that at all. She was always thinking before she made a remark in case she said something that would wound her husband, in case he found buried in it a sharp intended thorn which he would turn over masochistically in his tormented mind.

They came to a shooting stall and she said, ‘Would you like to try this then?’

‘Well …’ She put down the fifteen pence and he took the rifle in his hand, looking at it for a moment helplessly before breaking it in two. The woman gave him some pellets which he laid beside him, inserting one in the rifle after fumbling with it shortsightedly for some time. He snapped the broken rifle together and took aim: it seemed ages before he was ready to fire. She kept saying to herself, Why are you taking so long? Why don’t you fire? Fire.

He sighted along the rifle and fired, and one fat duck in the moving procession fell down. Again he aimed steadily and carefully, at one point putting the rifle down in order to wipe the sweat from his eyes, but then raising it and firing. He looked extremely serious and concentrated as if there was nothing in the world he liked better than shooting down these fat slow ducks passing in procession in front of him. And again he knocked one down. So he had a talent after all—another talent, that is, apart from his poetry. He steadily aimed and again hit a duck.

‘What do I get for that?’ he asked the woman excitedly.

The woman pointed without speaking to a miscellany of what appeared to be undifferentiated rubbish but which on examination defined itself as clay dishes, cheap soiled brooches and a teddy bear.

‘Take the teddy bear,’ Ruth suggested and he took it, handing it over proudly. She in turn gave it to Sheila who gravely clutched it like a trophy.

‘I didn’t know you could shoot,’ she said as they walked along together.

‘I used to go to fairs when I was younger,’ he replied, but didn’t volunteer any more. She was proud that he had won a prize though it was a not very plush teddy bear and she put her arm momently in his. He seemed pleased, and relaxed a little, but she wished that he would remove his jacket.

‘The prize wasn’t worth the entry fee,’ he commented as they walked along.

‘That’s true.’

‘All these fairs are the same. They cheat you all the time.’

She knew that what he was saying was true but she thought that he shouldn’t be repeating it so often: after all there were more things that they could talk about than the deceitfulness of fairs. When she had married him his conversation had been less monotonous and more enterprising than this, but she supposed that sitting in the house all day, every day, there wasn’t much new experience flooding into his life.

A woman on toppling heels and wearing blue-rinsed hair walked past them.

‘Did you see that woman?’ she asked. ‘Do you see her hair?’

‘What woman? I didn’t notice.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ she sighed.

Yet he had aimed carefully and with great concentration at the ducks as if more than anything else in the world he had wanted to shoot them down. He was pretty well as quiet as Sheila most of the time; she herself wasn’t like that at all, she liked to talk to people, that was why she worked in an office. She liked the trivia of existence. She would take stories home to him at night but he hardly ever listened to her or suddenly in the middle of what she was saying he would talk about something else. He might for instance say, ‘Do you think poetry is important?’ And she would answer, ‘I suppose so,’ and immediately afterwards, ‘Of course it is.’ And she herself would have been thinking about her boss whose wife had visited him in the office that day and how he had shown her round as if she had been a complete stranger. Or about Marjorie who had told her how she had thrown a frying pan at her husband with the eggs still in it.

And he would say, ‘It’s just that sometimes I wonder. Sometimes I …’ They had come to the Hall of Mirrors and she said, ‘What do you think? It costs fifteen pence.’

‘I don’t know. What do you think?’

Why was he always asking her what she thought? She wished he would accept some responsibility for at least part of the time. But, no, he would always ask, ‘What do you think?’ If only once he would say what he himself thought.

She didn’t know what a Hall of Mirrors would be like but she said aloud, ‘Why not?’ It was she who always walked adventurously into the future, throwing herself on its mercy without much previous thought.

‘Come on then,’ she said. ‘Let’s go in.’

Hugh and Sheila followed her into the large tent.

It was hilarious. When they entered they saw two people whom they assumed to be husband and wife doubled over with laughter in front of a mirror, the wife pointing at her reflection and unable to utter a word. The husband glanced at the three of them and at her in particular, raising his hands to the roof as if saying, ‘Look at her.’ Hugh stared at his wife angrily and she thought, ‘To hell with him. Can’t I even look at another man?’

Then she turned and looked in the mirror. Her body had been broadened enormously, her legs were like tree trunks, and her large head rested like a big staring boulder on massive shoulders. It was like seeing an ogre in a fairy story, in a world of glass, a short wide ogre so close to the earth that he might have been planted in it. She began to laugh and she couldn’t stop. Even Sheila was laughing and crying: ‘Look at Mummy she’s so fat.’ She looked so rustic in the mirror as if she had lived all her life on a farm and had only gained from it a disease which gave her eyes a staring thyroid look, and her body the appearance of someone suffering from advanced dropsy. The man smiled at her again—as if caught up in her simple laughter—and Hugh glowered at the two of them.

Then he himself turned and looked in an adjacent mirror. This particular one elongated his body so that he seemed very tall and thin and his head with its frail brow was like a tall egg on top of his stalklike body. He smiled without thinking and she laughed from behind him and so did Sheila, clapping her hands, and shouting, ‘Daddy’s so thin. Look at Daddy.’ She moved from mirror to mirror. In one she was squat and heavy and lumpish, in another her legs were as thin as the stalks of plants, climbing vertically to her incredibly shrunken waist. And all the time Sheila was running from one to the other excitedly. Hugh wasn’t laughing as much as she was, he seemed rather to be studying the reflections as if they had philosophical or poetical implications.

Most of the people in the tent were laughing so loudly and with such abandon that they were like occupants of an asylum, rocking and roaring and leaning on each other, hardly able to breathe. But though she laughed she didn’t abandon herself as helplessly as they did. And Hugh gazed at the reflections gravely as if they were pictures in an art gallery which he was trying to memorise.

She looked down at her slim body in the yellow dress as if to make sure that she wasn’t after all the distorted woman in the mirror, the gross heavy-rooted peasant with the swollen arms and the swollen legs. And all around her was the perpetual storm of laughter and the rocking red-faced people. And suddenly she too abandoned herself, doubled over, banging her fist on her knee, shrieking hysterically at the squat figure, making faces at her. Tears came into her eyes, she wept with a laughter that was close to pain, and in the middle of it all she saw the reflection of her husband, tall and incredibly thin, with the immensely frail tall egg perched on his shoulders, gazing disapprovingly at her.

She couldn’t stop laughing, it was as if a torrent had been released in her, as if she were a river in spate. And beside her the man and his wife were doubled over with laughter, their faces red and streaming, the man making faces in the mirror to make his reflection even more macabre.

Finally she stood up and made her way to the door, Hugh following her with Sheila. He was silent as if he felt that she had betrayed him in some way.

‘Didn’t you like that?’ she asked him. ‘It was really funny.’ And she began to laugh again, this time more decorously, as if at the memory of what she had seen, rather than at its present existence. Why on earth did he never let himself go? Ever? She was angry with him and gritted her teeth. She supposed that even when he had been working in the library he had been like that, sad and serious, gravely spectacled, a source of tall disapproval when women borrowed their romances or thrillers. But how on earth had he learned to be so dull?

The two youths who were wearing striped green and white scarves came back up the road again, shouting. Hugh pulled Sheila aside out of their way, turning his eyes from them.

Damn you, damn you, she almost shouted, why didn’t you go straight on? But she knew that he shouldn’t have done so and that she was being unreasonable, for after all the creatures she had just seen were quarrelsome, irrational, and violent. But was that what writing did for you, sitting day after day in your room and then drawing aside from the rawness of reality when you emerged into it? Oh my God, she thought, what is it I want? Joy, life … She listened to the steady beat of the music which animated the fair. In the old days she used to dance such a lot, now she didn’t dance at all. She even knew some of the tunes they were playing, nostalgic reminders of her youth. Paper roses,paper roses, she hummed to herself, as she walked along. But why couldn’t he take off his damned jacket? There were men passing all the time with bare torsos tanned to a deep brown and looking like gipsies, while by contrast Hugh seemed so pale even in this gorgeous summer because he never left his room. Damn, damn, damn. If only one was a gipsy, wandering about the world in a coloured caravan, without destination, without worry.

She wanted to dance, to sing, to shout out loud. But she didn’t do any of these things and she merely walked on beside Sheila and Hugh looking as demure as any of the other women she met, a member of an apparently contented family, while all the time the beat of the music throbbed around her and inside her.

They came to a place where there were small cars for the children to drive and she asked Sheila if she would like to go on one of them. Sheila gravely nodded and then paid the man with the money her mother gave her, stepping with the same unhurried gravity into one of the cars which ran on tracks so that there was no danger. Ruth watched her daughter as the latter gazed around her with the same unsmiling serious self-possessed expression and when one of the other little girls began to cry Sheila gazed at her with a faint distaste. It worried Ruth that her daughter should be so unsmilingly serene and while she was thinking that thought Hugh said, ‘She’s cool, isn’t she?’

‘Isn’t she?’ Ruth hissed back and Hugh turned to her in surprise.

‘I’m worried she’s so cool,’ Ruth continued in the same hissing tone. ‘She never smiles. She’s like a robot.’

‘What’s wrong with being cool?’ Hugh asked her.

‘I don’t know. Maybe she’s like you. Maybe she’ll be a writer.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ said Hugh, his face pale.

‘What I said. Maybe she should be a writer. Isn’t that a good thing? Maybe a writer doesn’t have to have emotions.’

‘I don’t understand what you’re trying to say.’

‘Oh skip it,’ said Ruth impatiently and watched her daughter driving past with the same unearthly competence and composure as she had noticed before, self-reliant, never bumping into anyone, never making a mistake.

‘Anyway,’ she said aloud, ‘what does your writing mean? This is the real world. What have you got to say about this? About the fair? You haven’t said anything. I don’t think you’ve noticed a thing.’ She was hissing like a snake and all the time he was staring at her with his pale hurt face among all the tanned people. Perhaps he thought the fair vulgar, beneath him; perhaps he thought that the music which recalled her youth to her was indecorous, inelegant, raucous.

They watched Sheila driving round and round in her small yellow car.

‘It’s because I don’t drive,’ said Hugh.

‘No,’ she almost screamed. ‘It’s nothing to do with that. Nothing at all to do with that. It’s your lack of feeling, your damned lack of feeling. She’s getting like you. Look at her. She’s like a robot, don’t you see?’

‘No I don’t see. She’s self-contained, that’s all. But I don’t think she’s like a robot.’

‘I don’t care what you say, I know.’

‘Do you want me to stop writing then?’ he asked plaintively.

‘You do what you want. Anyway I don’t think writing is the most important thing in the world, as you seem to.’

And all the time there throbbed around her the beat of the music, heavy, sonorous, plangent. Her body moved to its rhythm. And her daughter revolved remorselessly in her small car.

‘You’re shouting,’ said Hugh. ‘People are hearing you.’

‘I don’t care. I don’t care whether they hear me or not.’

The cars stopped and she leaned over and pulled Sheila towards her. She walked off ahead, Sheila beside her. It was as if she wanted to get into the very centre of the fair, its throbbing centre, in among the lights, the red savage lights, so that she could dance, so that she could feel alive, even in that place of cheating and deception, crooked sights, bad darts.

He was so dull, always asking her if poetry was important. And what should she tell him? Why was he doing it if he doubted its value so much? The fair was important: one could sense it: its brash reality had all the confidence in the world, its music was dominating and without inhibition. It was doing a service to people, even though the prizes were cheap and without substance. The joy of existence animated it, colour, music.

What’s wrong with me? she asked herself. What the hell is wrong with me? She watched a girl and a boy walk past, arm in arm, and she felt intense anguish like the pain of childbirth.

She hated her husband at that moment, he looked so pale and anguished and out of place. If only he would hit her, say something spontaneous to her, but he looked so perpetually wounded as if he was always trudging home from a war he had lost. The only time she had seen a look of concentration on his face was when he had been firing at the ducks.

She saw a great wheel circling against the sky with people on it, some of them shrieking.

‘I think I’d like some lemonade,’ she said aloud, and they walked in silence to the lemonade tent.

While they were in the tent a drunk man pushed his way past them swaying on his feet and muttering some unintelligible words.

‘Hey,’ she shouted at him but he pretended not to hear.

‘Did you see that?’ she said to Hugh. ‘He pushed past. He had no right to do that.’ She was speaking in a very loud voice because she was so angry and Hugh looked at her in an embarrassed way. She wanted to stamp her heels into the man’s ankles: but she knew that Hugh wasn’t going to do anything about it and so she said, ‘I don’t think I want any lemonade at all.’

‘That bugger,’ she said, referring to the drunk man, hoping that he would hear her, but he seemed to be rocking happily in a muttering world of his own.

Before she knew where she was—she was walking so fast because of her rage—she found herself away from the fairground altogether and in an adjacent park where she sat on a bench, seething furiously. When her husband finally caught up with her and sat beside her she felt as if she could pick up a stone and throw it at him, so great was her frustration and her loathing. Sheila sat down on the grass, cradling the teddy bear in her arms and saying into its ear, ‘Go to sleep now. Go to sleep.’ Its unblinking eyes with their cheap glitter stared back at her. She seemed to have forgotten about her parents altogether and was in a country of her own where the teddy bear was as real as or perhaps more real than her parents themselves.

‘Why didn’t you want lemonade?’ said Hugh.

‘If you must know,’ she replied angrily, ‘I didn’t take it because that man got ahead of us in the queue and you didn’t do anything about it.’

‘What was I supposed to do about it? Start a fight?’

‘I don’t know what you could have done. You could at least have said something instead of just standing there. You let people walk all over you.’

‘What people?’

‘Everybody.’

‘Perhaps,’ he said, ‘I should get a job then. It’s quite clear to me that you don’t want me to be writing.’

‘What on earth …’ She gazed at him in amazement. ‘What on earth has that to do with what I’m talking about? I don’t care whether you write or not. You can carry on writing as long as you like. I don’t care about that. It doesn’t worry me.’

‘You think I’m a failure. Is that it?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know whether you’re a failure or not. You’re never happy. You’re always thinking about your writing. And yet you never seem to see anything that goes on around you. I don’t understand you.’

‘And what about you? Do you see everything?’

‘I see more than you. You don’t care about the real world. You really don’t. You didn’t really want to come to the fair, did you? You think it’s beneath you.’

‘No,’ he said, ‘it wasn’t anything like that at all. It’s just that … Oh, never mind …’

Sheila was still talking to the staring teddy bear, quiet and self-possessed as she sat on the grass in front of their bench.

In the old days the two of them had gone out together and they would lie down beside the river that flowed through the glen and she would think that Hugh’s silence was very restful. But they would talk too.

What did they talk about in those early days that passed so quickly? Days passed like hours then, now hours seemed as long as days. She didn’t even know what he did with himself when she was out working, and even when she came home at night with her fragments of news he didn’t seem to be listening or, if he was, it was to some inner voice of his own, and not to her. She knew that she was jealous of that inner voice that tormented and obsessed him, that it was a part of him that she would never know, deep and dark and distant. What inner voice was there anyway beyond the fair, beyond the passing people and the music? She stared down at the grass which was green in places and parched in others. If Sheila hadn’t been there she might have walked away but she was there and she couldn’t leave her.

Sitting beside each other on the green bench they stared dully down at the ground. Eventually she got up. ‘We might as well go back and see the rest of the fair,’ she said. ‘After all that’s what we came for.’ Hugh got to his feet resignedly and followed her as did Sheila, cradling the teddy bear in her arms.

When they returned to the fair, she asked Sheila if she would like to go on the swings. She paid for her and watched her settle herself on one of them, she herself standing on the ground and watching her from below, while Hugh was silent at her side. Sheila sat on the swing turning round and round with the same unnaturally quiet self-possessed air. Sheila terrified her. She wondered if, while she was away at work, Sheila was learning to be like her father, distant, without feeling. Maybe Hugh was taking her away into his own secret unhuman world. She wanted to rush up to the swing and stop it and take Sheila into her arms and say to her, ‘This is the real world. This is all the world there is. Don’t you smell it? Don’t you hear the music? Enjoy it while you can. This is your childhood and it won’t come again.’

She turned and glanced at Hugh, but he was staring ahead of him, hurt and wounded, as if into a private dream of his own.

God, she thought, what is happening to us? Maybe I should leave him. Maybe I should take Sheila with me and leave him. Maybe I should take her into the centre of the fair and teach her to dance.

The swing had come to a halt and gravely as ever Sheila stepped off and walked over to her parents still clutching her teddy bear. She stopped beside them, staring down at her brown shoes, shy and serious.

Ruth took her by the hand and in silence they moved forward.

‘Would you like to go into the Haunted House?’ she asked Hugh but he didn’t answer. She didn’t want to go by herself, as she was superstitious and believed firmly in ghosts.

What had that Hall of Mirrors meant? What had been the significance of it? She had looked so squat and earthbound there. Was that what she was really like who once had danced with such abandon and joy?

She thought, I’d like to go to a dance just once. Just once to a dance so that I would let myself go. But Hugh didn’t like dancing. I should like to listen to music, she thought, the music of my early days when I had my freedom, before that silence descended. He has done more harm to me than I have done to him with his tall thin spiritual body and his brooding mind. If I had only known before my marriage … If only … But it was too late.

She was still alive but dying. The flesh—surely that was superior to the spirit, the soul.

There must be dancing in the world, joyousness and music.

But Hugh walking beside her was not speaking. She knew that he was hurt and angry, she could tell by the pallor of his face, by his compressed lips. What had he learned at the fair? Had he had any ideas for a poem? She didn’t like his poems anyway, she didn’t pretend to understand them, she was not a poseur as some people were. There were lots of people who would say that they liked a poem even if they didn’t understand it, in order to be ‘with it’. She, on the other hand, was the sort of person who would speak out, who had definite opinions.

She wasn’t enjoying the day one little bit, she knew that: everything was so hot and sticky. She wanted to be at the centre of things just once, she wanted to do something dramatic, something that she would remember in later years. She wanted to throw perfect darts, hit a perfect target…. No, on second thoughts, she didn’t even want to do that, she merely wished to laugh and enjoy herself and have a happy untidy day so that she could go home and plump herself on the sofa and say, ‘Gosh, how tired I am.’ But that wasn’t likely to happen.

The three of them walked together but she seemed as far away from the other two as she could possibly be. And all the time Hugh remained wrapped in his silence as in a dark mysterious cloak.

They came to a tent outside which there was a notice saying SEE THE FATTEST WOMAN IN THE WORLD. She stopped and looked at the other two and said, ‘I want to see this. Even if you don’t,’ she added under her breath. She paid forty-five pence for the three of them and they entered the tent. Sitting on a chair—she thought it must be made of iron to sustain the weight—there was the fattest grossest woman she had ever seen in her whole life.

The head was large and the cheeks were round and fat and there were big pouches under the treble chins. The breasts and the belly bulged out largely under a black shiny satiny dress. With her huge head resting on her vast shoulders the woman was like a mountain of flesh, and in close-up Ruth could see the beads of sweat on her moustached upper lip. The hands too were huge and red and fat and the fingers, with their cheap rings, as nakedly gross as sausages. Crowned with her grey hair and almost filling half the tent, the woman seemed to represent a challenge of flesh, almost as if one might wish to climb her. Ruth gazed at the immense tremendous freak with horror, as if she were seeing a magnification of some disease that was causing the flesh to run riot. Sunk deep in the head were small red-rimmed eyes, and in the vast lap rested the massive swollen hands. And yet out of this monstrous mountain, vulgar and sordid, there issued a tiny voice saying to Sheila:

‘Do you want to talk to me, little girl?’

And Sheila looked up at her and burst out laughing.

‘You’re just like Mummy in the tent,’ she shouted. And she ran over and clutched her mother’s hand, laughing with a real childish laughter. Pale and tall, Hugh was watching the woman and Ruth thought of the vast body seated on a lavatory pan in some immense lavatory of a size greater than she had ever seen, and as she imagined her sitting there she also saw her spitting, belching, blowing her enormous nose. She was sickened by her, by her acres of flesh, by the smell that exuded from her.

She imagined the fat woman dying in a monstrous bed, people bending over her as she breathed stertorously, beads of sweat on her moustache.

And Sheila was still laughing and shouting, ‘She’s just like you, Mummy,’ and tall, with egg-shaped head, Hugh gazed down at her, ultimate flesh seated on its throne.

Ruth felt as if she was going to be sick; the image in the mirror had come true in the stench of reality; the legs like tree trunks, the large red hands, the sausage-like fingers were there before her. She ran out of the tent, the bile in her mouth, and Hugh followed her with Sheila. In the clean air she turned to Sheila and said, ‘There’s the Big Wheel. Do you want to go on it? Your father can go with you if you like.’

‘All right,’ said Hugh, as if some instinct had told him that she wanted to be alone.

She watched them as they got into their seats, and then from her position on the ground below she saw them soaring up into the sky, descending and then soaring again. She waved to them as they turned on the large red wheel. And Hugh waved to her in return but Sheila was staring straight ahead of her, cool and self-possessed as ever. Up they went and down they came and something in the movement made her frightened. It was as if the motion of the wheel was significant amidst the loud beat of the music, the crooked guns and darts. As she saw the two outlined against the sun she knew that they belonged to her, they were her only connection with reality, with the music and the colour of the fair. If something were to happen to them now what would her own life be like? She almost ran screaming towards the wheel as if she were going to ask the operator to stop it lest an accident should happen and the two of them, Hugh and Sheila, would plummet to the ground, broken and finished. But she waited and when they came down to earth again she clutched them both, one hand in one hand of theirs.

‘That’s enough,’ she said, ‘that’s enough.’

The three of them walked to the car. She unlocked the door and got into the driver’s seat, Hugh beside her wearing his safety belt, and Sheila in the back.

Sheila suddenly began to become talkative.

‘Mummy,’ she said, ‘you were fat in the mirror. You were a fat lady. You had fat legs.’

Ruth looked at Hugh and he smiled without rancour. They were sitting happily in the car and she thought of them as a family.

‘Did you think of anything to write about?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ he said but he didn’t say what it was he had thought of till they had reached the council estate on which they lived.

He then asked her, ‘Do you remember when we were at the shooting stall?’

‘Yes,’ she said eagerly.

‘Did you notice that the woman who was giving out the tickets had a glass eye?’

‘No, I didn’t notice that.’

‘I thought it was funny at the time,’ Hugh said slowly. ‘To put a woman in charge of the shooting stall who had a glass eye.’

He didn’t say anything more. She knew however that he had been making a deliberate effort to tell her something, and she also realised that what he had seen was in some way of great importance to him.

What she herself remembered most powerfully was the gross woman who had filled the tent with her smell of sweat, and whose small eyes seemed cruel when she had gazed into them.

She also remembered the two boys with the green and white football scarves who had gone marching past, singing and shouting.

She clutched Hugh’s hand suddenly, and held it. Then the two of them got out of the car and walked together to the council house, Sheila running along ahead of them.