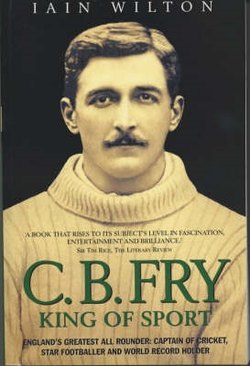

Читать книгу CB Fry: King Of Sport - England's Greatest All Rounder; Captain of Cricket, Star Footballer and World Record Holder - Iain Wilton - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

OXFORD IDOL

ОглавлениеAlthough Fry had little money when he went to university, he began his Wadham career with many advantages. By winning his scholarship, he had shown that he was unlikely to struggle with the academic demands of his course. He had probably guessed that his good looks would attract admiration, while his sporting prowess was likely to win him new friends. (Indeed, between leaving school and reaching university, C.B. further strengthened his cricketing credentials by playing – albeit unsuccessfully – for Surrey, the county of his birth.)1 Furthermore, he arrived at Oxford with a mind which had been broadened by travelling to France, where he found time for ice skating, lectures at the Sorbonne and frequent visits to the Café St Michel (frequented by Zola, Clemenceau and Monet). In addition, he enjoyed the company of another guest at the apartment in which he stayed: ‘a young American lady called Miss Sproull, in Paris to study singing at the Conservatoire.’2

Wadham was not one of Oxford’s oldest colleges, having been founded by Nicholas and Dorothy Wadham in 1610. After her husband’s death, Dorothy took charge of the college’s construction and showed her practicality by insisting that the library was built above the kitchen to keep its books dry. Equally practical – but, ultimately, unsuccessful – was her suggestion that the college statute should end her widowhood by obliging the first Warden to marry her.

In its relatively short history, Wadham had produced a number of interesting and influential figures, especially in the seventeenth century. In an early demonstration of its independence, it welcomed Carew Raleigh to its ranks almost immediately after his father, Sir Walter, had been executed on the orders of James I. Continuing the nautical connection, the College was the alma mater of Robert Blake, the victor of the Battle of Santa Cruz.

Later in the seventeenth century, after the English Civil War, Wadham gained one of its most distinguished Wardens, John Wilkins. Although his initial appointment owed much to the identity of his brother-in-law, Oliver Cromwell, Wilkins proved to be a remarkable academic and a particularly forward-looking scientist. He wrote books on how to reach the moon and conducted experiments into flying – predicting one day humans would wear wings just as readily as boots. But in view of his family connections, it is ironic that Wilkins is best remembered for creating the Royal Society, which grew out of weekly meetings held in his College rooms.

After a comparatively uneventful eighteenth century, Wadham returned to the fore in the early Victorian age when it housed the leading philosophers of the Positivist movement – Congreve, Beesley, Bridges and Harrison. When Fry joined Wadham, Frederick Harrison was still active in College life and provided some interesting links with Oxford’s distant past.

Harrison had arrived at the university as far back as 1848 when ‘there was no north Oxford and you walked straight from Wadham into fields and market-gardens with relics of earthworks built in the Civil War.’3 Early in his university career, he met an extraordinary man named Routh who, despite being in his nineties, was still President of Magdalen College – a post he had held since 1784. Through this meeting, Harrison linked the Oxford of Fry’s age with its seventeenth-century past because Routh told him that, in his youth, he met an elderly lady who had seen Charles II exercising his spaniels in Magdalen Grove. On other occasions, Routh regaled guests with the story of how, as a young don, he had seen undergraduates hanged on the orders of the Vice-Chancellor. As C.B. later discovered to his cost, the Vice-Chancellor could still be the arbiter of justice for undergraduates. (Fortunately, the death sentence had since fallen into disuse.)

Although Oxford still had these links with an archaic past, Fry joined the university when it was benefiting from some modernising reforms. At the end of the 1870s, the first two colleges for women (Somerville Hall and Lady Margaret Hall) had been established; in the 1880s, Oxford dons finally received permission to marry and, by the early 1890s, students were attending far more lectures outside their own colleges and, therefore, mixing with a much wider variety of people than only 20 years before.

A minority tried to resist Oxford’s march towards the twentieth century. There was still no formal retiring age for university appointments and McGrath, for instance, followed Routh’s example by remaining as Provost of Queen’s College until his death, aged over 90, in the early 1900s. He had retained his position despite being confined to bed for the last 20 years of his life and paying someone else to perform his college duties. Another member of Oxford’s ancien régime was Lord Queensberry, who objected to the advent of the internal combustion engine and asked the city’s police for permission to shoot any motor-cyclist exceeding 20 miles an hour.

Fry arrived at a fascinating time in Oxford’s history and was fortunate to join a college that provided more than enough elegance and intimacy to compensate for its relatively unglamorous status. Joseph Wells, a don at Wadham in the 1890s (and, subsequently, its Warden), loved ‘the studied simplicity which is the great secret of Wadham’s beauty’ and, as late as the 1930s, John Betjeman could describe it as ‘remarkable as having not a single ugly or modern building in its make-up.’

For Fry, another factor in Wadham’s favour was its size. As a comparatively small college, it had few cliques, a strong sense of community and a pressing need to find new players for its sports teams. Moreover, because it had become relatively unfashionable, Wadham attracted few particularly wealthy applicants and its annual intake included students from a cross-section of upper-middle and solidly middle-class society. As several of C.B.’s contemporaries have confirmed, these factors – beauty, intimacy and fraternity – were probably the most memorable characteristics of the college in the early 1890s and contributed to many happy and outstandingly successful university careers. Indeed, when Fry arrived, in autumn 1891, Wadham’s students were about to end its relative obscurity and return it to the forefront of Oxford life.

As the senior scholar amongst the new arrivals, Fry had the privilege of being allocated rooms that were amongst the college’s best (and, as he later discovered, most expensive) accommodation. As well as being oak-panelled, they provided him with a view of the front quadrangle and the statues of Wadham’s founders. At dinner, too, he was reminded of his elite status as the scholars were seated together. As he recalled in Life Worth Living, ‘At the scholars’ table sat my four unknown colleagues. Opposite me sat one of them, of whom I immediately took notice. I knew his name was Smith. I saw that his hair was rather untidy, being of the kind that stands upright unless prevented. He had a long lean brown face and an impudent nose, but very remarkable eyes. They were the colour of a peat pool on Dartmoor, full of light, and fringed by luxuriant silky eye-lashes.’ In turn, F.E. Smith was left with an abiding memory of his first meeting with Fry. According to the biography written by his son, the future Lord Chancellor was instantly struck by C.B.’s good looks and obvious athleticism: ‘There was C.B. Fry, the handsomest man of his day, a Greek god, so beautiful in face and body that he might have been wrought by the chisel of Praxiteles, with broad shoulders and narrow hips. Smith noticed that Fry had the true athlete’s walk, like an animal on pads, and could never see him without thinking of Francis Thompson’s “the stealthy terror of the sinuous pard”.’

After dinner, the new scholars set off towards C.B.’s rooms for coffee. They were soon joined by a tall Scottish postgraduate, who introduced himself as McVey. Discovering that his Christian name was Tom, Smith rechristened him ‘Tam’ and continued teasing him for the remainder of his, and Fry’s, Oxford career. Within days C.B. was also on the receiving end of Smith’s humour.

On the first Sunday of term, Fry’s rooms were again the setting for a lengthy, and leisurely, ‘breakfast’ which began at about ten o’clock and, in reality, took the form of substantial lunch, washed down by Oxford ale. After the meal, C.B. and his guests walked into the quadrangle towards the statues of the Wadhams, on a ledge half-way up one of the quad’s four walls. Guessing that his new friend would be unable to resist a challenge, Smith expressed doubts about whether Fry was capable of planting a kiss on Dorothy Wadham – something the first Warden had been reluctant to do. Smith’s words had the desired effect and C.B. rose to the bait. Things began well:

I climbed successfully while an admiring semicircle offered advice below. The first few feet required my full attention, but I surmounted them and turned round in triumph, with my arm round Dorothy’s cold waist. My friends had vanished, except their heads protruding from the windows on the nearest stair. Below stood the Sub-Warden …

‘Mr Fry, Mr Fry,’ he said, ‘come down please, Mr Fry, Mr Fry.’ As always happens in such adventures, it took me quite a long time to come down where I had much more quickly climbed.

‘Mr Fry, Mr Fry,’ said the Sub-Warden in a gentle reproving voice, ‘you have not long been a member of this University, but would you, Mr Fry, wish a member of any other College to see you, on Sunday morning, in flannels and slippers, climbing up the face of the College on an amatory adventure?’

When C.B. saw the Sub-Warden, the Reverend Henderson, the following morning, he was asked to ensure that in future his energy and enterprise were put to more conventional uses. Fortunately, the reprimand was concluded on a light-hearted note: ‘Please do not kiss the wife of the Founder again in public. And, anyhow, why kiss a stone lady, Mr Fry, Mr Fry?’

Although the incident was never forgotten by Fry, Smith seems to have been forgiven fairly rapidly. F.E. soon moved into the rooms opposite C.B.’s and two of the university’s new stars started breakfasting together every day. Smith would often use these early morning meetings to read out the beginning and end of the latest speech that he had drafted for use at the Oxford Union. ‘For the rest,’ wrote Fry, ‘he relied on enlightened improvisation.’

The bond between the two scholars was further strengthened when one of their tutors, Herbert Richards, caused them considerable inconvenience by lecturing on Saturday mornings. With Smith keen to speak at various political meetings and Fry seeking a place in Oxford’s football team, they decided to miss some of his lectures. Their absence did not go unnoticed and both were ‘gated’. For someone of C.B.’s ingenuity and athleticism, however, this did not present an insuperable difficulty. He discovered that a builder’s yard backed on to the rear of the college and found that he could use one of its ladders to get into and out of Wadham’s grounds. For the rest of their university careers, this discovery meant that C.B. and F.E. could enter and leave the college without recourse to the porter who kept the official book of entry. Smith and Fry formalised this arrangement by creating the Wadham Cat Club. As one of Birkenhead’s biographers wrote:

Of the many clubs then existing at Oxford, the Wadham Cat Club imposed what were probably the most severe qualifications for membership. The aspirant had to prove his courage and agility by climbing out of Wadham, getting over the spiked railings and walls of Trinity, moving thence to the invasion of Balliol and St John’s before returning to Wadham. If, on reaching Wadham, the aspirant could steal the keys from the sleeping porter, not only was his admission to full membership secured, but he also won a dinner at the Clarendon.4

Fry’s athleticism was demonstrated in more conventional ways as well. Ignoring the opinions of some dons, who felt that any time devoted to sport was wasted, C.B. soon provided two extraordinary exhibitions of his athletic ability. In his first term at Oxford, he was easily the most impressive figure in the Freshmen’s Sports, winning the 100 yards, the 120 yards hurdles, the high jump and the long jump (by over two feet). At the Wadham Sports, on 27 November, he was, understandably, even more dominant. Despite ignoring his best event, the long jump, he won seven others – including, surprisingly, the hammer and shot-put.

Overcoming the problems created by Richards, C.B. also devoted part of his first term to football. He was determined to build on his success at Repton and set his sights on winning a Blue. After a poor performance in one of his earliest games, against Notts County, his prospects seemed to suffer a setback: the Oxford Magazine, for example, reported that ‘Fry, though occasionally brilliant, was not at all safe in kicking, and frequently found a forward too good for him.’ Astonishingly, however, C.B. was not merely playing for Oxford but making his England début only a month later.

Fry’s unexpected promotion can be attributed to two factors. First, England’s opponents, Canada, who were on a lengthy British tour, had proved to be a far poorer team than was originally expected. Second, C.B. was fortunate that England’s key selector, N.L. Jackson, was an enthusiastic supporter of amateur football. Indeed, ‘Pa’ Jackson had created the Corinthians because of his conviction that the best amateurs needed to play together on a few occasions each season. This, he believed, would enable them to meet the best professional sides on more equal terms: in addition, he hoped it would improve England’s record against Scotland which, prior to the Corinthians’ formation, had been exceptionally poor. As C.B. had already played for another leading amateur team, the Casuals, as a schoolboy, Jackson would have been aware of his talent before he reached Oxford and he was, no doubt, keen to give C.B. every encouragement to become a committed Corinthian.5

There were many reasons for the shortcomings of the ‘Canadian’ team. As there had been too few good players in their own country, the tour organisers brought in reinforcements from the United States, a move that strengthened the side on paper but in practice made it less representative and harmonious than before. Moreover, the tour lost some of its appeal through being organised by people whose motives were purely financial and the team dissipated any remaining goodwill by indulging in a rough style of play that kept referees unusually busy. Above all, the public lost interest in the Canadians’ visit because the tourists were unable to compete effectively with most of their opponents. In total, ‘Canada’ played almost 60 games but won only 13. The length of their fixture list was one factor which could be used to excuse their poor performance. The Football Annual conceded: ‘… in justice to the team, it must be said that they had a very heavy programme to get through, with few real intervals of rest. In all, indeed, they carried out 58 fixtures, and it said much for their pluck as well as their good faith that they fulfilled their engagements to the last, in the face of a steady reduction of their numbers from accidents and other causes.’ In the week preceding their match against England, on 19 December 1891, the Canadians played no fewer than three matches, against Ardwick, Port Vale and Northwich Victoria, and lost them all.

In view of the Canadians’ weaknesses, Jackson seems to have regarded the game as a convenient opportunity for England to be represented by amateurs, whom he regarded as gentlemen rather than professionals, who played the game for a living. It also gave him the chance to cap a promising young player (and prospective Corinthian stalwart) like Fry.

Whatever the precise thinking behind the team selection, C.B. was chosen to play for England alongside 10 other amateurs. Although some came from prominent clubs – like Nottingham Forest, the Casuals and the Corinthians – others played for teams which had a far lower profile and, from today’s perspective, it is hard to believe that England could be represented by footballers from ‘old boy’ sides like the Old Foresters or Old Brightonians.

In the event the amateurs were good enough to thrash ‘Canada’ 6-1 but the ‘Old Athlete’, writing in the Athletic News, was unimpressed by the England line-up. In his view, ‘the scratch lot which met the Canadians at The Oval on Saturday no more represented the football strength of England than would an eleven were I in it.’ He was also critical of Fry’s performance, saying C.B. had made mistakes and was ‘hardly up to International form yet.’

However, one cannot be entirely dismissive about the Englishmen who took part in this one-sided and poorly attended match. Seven had won, or went on to win, England caps against far more formidable opponents. Furthermore, whatever the shortcomings of the fixture, it was an extraordinary honour for Fry to be selected, aged just 19, to represent his country at football. It also meant that, before the end of his first term at Oxford, he was not only a leading scholar at one of the world’s best universities but, remarkably, a county cricketer and an international footballer as well.

Having played for his country in his first term, C.B.’s attention returned to his original objective of winning a footballing Blue in his second. He achieved his ambition in March 1892 when he was selected to play, at left-back, against Cambridge. For Fry, and his team-mates, this proved an unhappy experience. One of their forwards was injured within the first few minutes and his colleagues were subsequently guilty of ‘probably the worst shooting ever seen in a Varsity match.’6 Overall, the quality of play in the first half was scrappy but the two sides did appear, at least, evenly matched. In the latter part of the game, however, Cambridge assumed the ascendancy and, according to The Football Annual, ‘the collapse of the Oxford men in the second half was not a little startling.’ They conceded five goals and, despite mounting regular attacks, a brilliant performance by the Cambridge goalkeeper, L.H. Gay, prevented them from scoring more than once in reply. To add to the disappointment of a 5-1 thrashing, Fry, playing out of position, was held responsible for two of the Cambridge goals, with one account blaming his ‘fancy kicking’.7 On the other hand, C.B. seems to have attributed the defeat to his colleagues. After the match he was reported to have said ‘I never want to play again with such a lot of **** crocks.’8 It was perhaps the first indication that he could lose patience with team-mates who lacked either his dedication as a sportsman or his abundant natural gifts.

Within weeks of winning his first Blue, Fry secured his second – representing Oxford in the Varsity athletics match which, like the football fixture, was held at the Queen’s Club in Kensington. Although C.B. came fourth (and last) in the high jump, and Oxford lost by five events to four, he still had every reason to feel satisfied with his performance. Not only did he win the long jump but, in doing so, he broke both the Varsity and British records, jumping 23 feet 5 inches. It seems to have been a text-book affair as, in Fry’s words, ‘I got a beautiful take-off from the board and a splendid lift-up, and felt very neat in the air.’ The Times agreed, praising C.B. for ‘a wonderful jump taken in brilliant style’ and adding that the spectators had been treated to an eventful meeting, ‘which Fry’s great leap will long render famous.’

In later years, alas, C.B. added extra drama – and distance – to an achievement which needed no such embellishment. In Life Worth Living, he claimed to have taken off nine inches behind the board and, therefore, leapt over 24 feet. Moreover, in an admiring pen-portrait of Fry, published in 1951, Denzil Batchelor claimed his friend had been hindered by ‘a cracked wooden take-off board which forced him to jump off the track at least nine inches behind the starting line’ [emphasis added]. Significantly, no such claims had been made in Myers’ biography, which was published much nearer the time when C.B. felt less need to inflate his performances.

In the summer of 1892, C.B. had the opportunity to complete his hat-trick by adding a cricket Blue to those already won for football and athletics. It was unusual for any undergraduate to record such a prestigious treble during the course of an entire Oxford or Cambridge career; for C.B. to do so in his first year would confirm that his was a truly exceptional sporting talent.

In the fourteen-a-side Freshmen’s cricket match Fry provided immediate proof that he would be a strong contender for a place in Oxford’s Varsity match side. He top-scored with 118 in the first innings but probably earned more acclaim for hitting 53 out of 66, in poor light, during the second. As a bowler, too, he enjoyed considerable success and took 10 wickets in the match – prompting Wisden to describe him as ‘the hero of the game’. But although C.B.’s bowling was effective, its fairness was called into question. The Oxford Magazine conceded it would be ‘charitable to suspend one’s judgement’, but added the Delphic assessment ‘from the pavilion it looked first cousin to a throw.’ Its comments removed the gloss from a début which had yielded a century, a fifty and 10 wickets for barely 100 runs.

In his next match, playing for Sixteen Freshmen against the Oxford Eleven, C.B. suffered two disappointments as a batsman but enjoyed further success as a bowler, conceding only 58 runs from 43 overs and picking up six wickets in the process. Such performances earned him a place in the university team and he immediately justified his selection by hitting 105, by far the highest score, against the Next Sixteen.

Although Fry scored a decisive half-century in Oxford’s first match against a county side (Lancashire), his bright start to the season was followed by an alarming slump in form. He achieved the unwanted distinction of registering a duck in three consecutive fixtures and fared little better in a twelve-a-side match, against the M.C.C., in which he was dismissed for 8 and 1. His bowling was also affected and became less penetrative than before. Even a friendly game, for the Peripatetics, proved a struggle: although he took two wickets, he was dismissed for another duck as his side struggled to 41-7 in response to the Queen’s College score of 244-6.

Two days later, he found that form can return just as rapidly as it disappears. In a match against Somerset, he played the central role in steering Oxford to victory, taking four wickets in the first innings and then scoring his maiden first-class century (110), despite facing a strong attack which included the Australian Test bowler, Sammy Woods. In the words of Wisden, ‘Fry played wonderfully well.’

Despite his obvious inconsistency, C.B. retained his place in the Oxford XI for the Varsity match against Cambridge. In doing so, he became only the ninth man from Wadham to play in the fixture – and the first since H.V. Page and the unfortunately named Edward Bastard in the mid-1880s. More importantly, his selection enabled him to complete his hat-trick of Blues. It seemed that he would have little else to celebrate as Cambridge, led by Stanley Jackson, a future England captain, were regarded as much the better side.

Expectations of a light blue victory were further increased when Oxford lost their opening batsmen, Lionel Palairet and R.T. Jones, without a run on the board. Their replacements, Fry and Malcolm Jardine (father of Douglas), had to rebuild the innings under enormous pressure from an extremely large and equally partisan crowd. According to Myers, Fry felt ‘abjectly nervous’ before going out to bat. ‘As a rule,’ he continued, ‘nervousness made him stiffer and slower than usual but on this occasion the effect was precisely the opposite,’ and C.B. got off the mark by cutting a ball from Jackson, even though the cut was one of his least favoured shots.

The Fry–Jardine partnership succeeded in restoring respectability to the Oxford score. According to Life Worth Living, they ‘put on about 100’ for the third wicket before Fry was bowled by Jackson. In reality, C.B. was caught at the wicket and the two batsmen had added 75. But although the partnership was smaller than C.B. later suggested, it was described as ‘a capital exhibition of cricket’9 and its value to Oxford was impossible to overstate.

After Fry’s departure, Jardine continued to bat effectively and proceeded to make 140 – the second biggest innings in Varsity match history. It was to be Jardine’s only first-class century but atoned for the ‘pair’ he had recorded against Cambridge three years earlier. As Vernon Hill also scored a century, and added 178 with Jardine, Oxford’s final total (365) represented a great recovery from the depths of 0-2.

When Oxford fielded, their position was further strengthened by the behaviour of one of the Cambridge players. Although Gerry Weigall top-scored with 63, he ran out three of his side’s most dangerous batsmen – including its captain. To add insult to injury, Weigall sent the masterly Jackson to his fate with the words, ‘Go back, Jacker, I’m set.’

Thanks to the combined efforts of their four main bowlers and one eccentric Cambridge batsman, Oxford gained a first innings lead of 205. However, their opponents fared better when they followed on and made up plenty of lost ground. After steady scoring by most of their batsmen, Cambridge reached 388 – setting Oxford 184 to win. Once more, sensible batting by Fry (27) and Jardine (39) helped their side recover from a poor start and, although Oxford slumped to 99-4, Palairet steered his team to a five-wicket victory with an undefeated 71. By the standards of the time, it had been a high-scoring game – 35 wickets generating 1,100 runs. With Oxford’s recovery, and then a Cambridge fightback, it had also been a match of fluctuating fortunes, with the final result confounding all pre-match predictions. Fry and his colleagues had the satisfaction of securing a convincing win, at Lord’s, ‘against a Cambridge eleven which should have outgunned them in all departments.’10 It was, Wisden concluded, ‘a most brilliant victory’ – and enabled C.B.’s first year at Oxford to end on an appropriately high note.

In 1892, as in the previous year, Wadham attracted some new undergraduates who would enjoy glittering careers at the university and, subsequently, in the outside world. They included John Simon, who made his name in the Oxford Union, became an extremely successful lawyer and held many of the most important posts in British politics. With Simon moving into rooms beneath Smith, and F.E. continuing to live opposite Fry, the college found itself with the greatest concentration of talent in Oxford.

Of the new arrivals, F.W. Hirst, already an influential Liberal economist, provided perhaps the best account of an early encounter with C.B. He recalled that, in November 1892, William Gladstone visited Oxford’s Sheldonian theatre to deliver the first Romanes lecture. At the time Gladstone was in his fourth spell as Prime Minister and a huge crowd was keen to hear him speak. Indeed, Hirst and Fry felt obliged to scale the railings to ensure their places in the audience. Their exertions were worthwhile:

Mr Gladstone was in excellent voice and from time to time we undergraduates in the gallery punctuated his oration with vociferous applause. Thus, when we were told how in the fifteenth century, Oxford was reduced by the persecution of the Lollards and ‘by the indolence of the Fellows’ who were an incubus on the University, the whole gallery rose and cheered wildly, while our seniors, sitting below, tried to look unconscious, or at least more energetic than their medieval predecessors. Then again when Gladstone recited epigrams on the different ways in which George I dealt with the two Universities – Tory Oxford and Whig Cambridge – sending a troop of horse to Oxford and a present of books to Cambridge, because Oxford wanted loyalty and Cambridge wanted learning, the reference to Cambridge was received in the gallery with boisterous delight.

The Prime Minister, too, enjoyed his time in the city. He had been an Oxford undergraduate in the early nineteenth century and had happy memories of the Union, where his political career had started.

C.B.’s presence at the Sheldonian showed that he retained the interest in public speaking which had first become apparent at Repton. Wadham gave him plenty of opportunities to add to his experience and develop his skills. After joining its Debating Society at the beginning of his first term, Fry became a regular participant in the discussions of the College’s Literary Society in his second year. However, neither society was concerned solely with the intellectual stimulation of its members. In the case of the Literary Society, in particular, attendance had an added incentive. As Smith’s ‘scout’ told one of his biographers, Ivor Thomas, ‘the chief literary attraction has always been the hot beer.’ The presence of alcohol helps to explain why the records of each society contain numerous references to confused and disruptive behaviour. In 1892, for example, after the Debating Society considered the case for ‘the immediate evacuation of Egypt’ (which F.E. and C.B. opposed), the minutes record that, ‘During public business Mr Fry, after having been several times called to order, was fined 1 shilling by the President.’ Two weeks later, it was recorded, ‘Mr Fry, having refused to pay his fine, had been struck off the Society’s books’ although, after a procedural dispute, he was reinstated. In 1893, Smith’s promotion to the presidency of the society did nothing to improve order and, after one debate, ‘Private business consisted of a series of sallies from Mr Anstie and Mr Fry, who sat together on a window seat and vied with each other in the compilation of wretched, scurrilous witticisms at the expense of the President.’

There were many other occasions when Fry made a sensible contribution to proceedings. In his first year, for instance, he returned to one of his favourite themes to move the motion, ‘That this House believes in ghostly apparitions’. According to the minutes, ‘His speech, which lasted fifteen minutes, was rendered impressive by the Theatrical Gestures and exciting tales which he treated the House to’, but they did not convince everyone in the audience and ‘Mr Hodges proceeded to cast doubts on the veracity and respectability of the Hon. Proposer’s stories.’ Moreover, as someone at Repton had already observed, C.B. was more than willing to oppose – ‘from sheer love of argument’ – cases in which he clearly believed. After arguing, in 1892, that ghosts existed, he was happy to put forward the opposite argument when, in 1893, Smith moved a motion ‘That in the opinion of this House supernatural apparitions are possible’.

C.B. and F.E. also found themselves on opposing sides when the Debating Society considered the role of English landlords: Fry supported the contention that they ‘fail in their duty to the country’ while Smith was keen to defend them. More bravely, Fry opposed him in a debate about temperance, a subject on which Smith was known to have particularly forthright views – his reputation at the Oxford Union having been built, in part, on the way in which he treated temperance supporters. Indeed, C.B. recalled, in Life Worth Living, that F.E. was responsible for one of the most extraordinary speeches he heard as an occasional visitor to the Union: ‘Sir Wilfrid Lawson, MP, the temperance advocate, came down to speak and was attacked by F.E. in the most impudent speech I have ever heard, and about the wittiest. The point was that Sir Wilfrid had inherited an exquisite cellar of wine from his father, and made a public show of its destruction. F.E.’s animadversion on the iniquity of this sacrilege was as superb as it was devastating.’

It seems the Debating Society’s most memorable moment had nothing to do with any debate yet, inevitably, Smith was still at the centre of the action. In Hirst’s words:

I have never laughed so much in my life as on the night when he [Smith] introduced Anstie, disguised as McVey’s uncle in the garb of a Scottish laird, into the Wadham Debating Society, and gravely asked Simon, who was then President, to allow the old gentleman to keep on the battered top-hat, which half-concealed a wig of red shaggy hair. It had been put about that the laird was going to pay McVey’s debts, and the whole college was in hopeful suspense until the imposture was discovered.

Fry was a less enthusiastic member of the Wadham Literary Society. He had joined it in his third term, in May 1892, but did not become particularly active in its proceedings until his second year. While it provided another opportunity for college members to improve their speaking skills, it required rather more work than the Debating Society: each week a speaker had to write a paper and read it out at the start of the meeting to stimulate a discussion. After C.B. had commented on a paper about Marco Polo, and taken part in a discussion which concentrated on snakes and phallic worship,11 he appeared to make his first meaningful contribution after listening to a paper on Abraham Lincoln. According to the minutes, ‘Mr Fry said that the feud between the North and the South was like the feud between England and Scotland. The North was jealous of the wealth of the South. He defended the South for their courage and patriotism and wished that the South had won.’ It is likely, however, that such comments were primarily designed to antagonise the paper’s author, ‘Tam’ McVey.

In February 1893, the Society held one of its meetings in C.B.’s rooms for the first time, when members considered a paper on ‘The Pleasures of Sadness’ – in music, for example. But it was not until his third year that Fry was finally persuaded to produce some papers of his own and, on each occasion, he caused controversy.

In January 1894, after ‘Mr Smith informally congratulated the Secretary on having secured a paper from Mr Fry’, C.B. addressed the Literary Society about Gray. The minutes show that ‘after a florid opening in which (inter alia) a poet’s brain was compared to a photographer’s plate’, Fry outlined Gray’s background and the influences which affected his work. Although F.E. praised the paper, ‘Mr Willimott at some length and with interruptions was understood to question, under colour of an allegory, the genuineness of the manuscript recited.’ Furthermore, the President had been expecting Fry to speak about Zola instead. Four months later, C.B.’s second paper proved even more controversial than the first. No sooner had he arrived at the meeting than he was offering his apologies and explaining that after preparing the requisite paper, he had lost the book in which it was written. His audience was unconvinced and even an attempt to recover the situation, by letting him read someone else’s paper on Keats, ended in embarrassment when C.B. failed to decipher the handwriting.

After these unfortunate episodes, Fry attended a diminishing number of Literary Society gatherings but the minutes reveal that he ‘noted the lack of chivalry in women’ in one meeting, praised Kipling’s poetry (but criticised his tendency to be ‘too pertinently blasphemous’) in another and, finally, after considering ‘The Indian Currency Question’, expressed his belief that ‘if matters are so bad we ought not to keep India any longer.’ Little did he realise that, despite failing the I.C.S. exam, India would still play a major role in his life.

In view of his interest in public speaking, many have wondered why Fry never joined the Oxford Union. Although he was happy to attend some of its debates, when outstanding debaters, like Smith or Belloc, were speaking, he declined several earnest invitations to become more actively involved in proceedings. In May 1893, for example, Earl Beauchamp wrote to F.E., urging him to recruit Fry as a speaker. There was almost a note of desperation in the letter, reflecting the fact that C.B. would have brought added glamour to the Union. (The Earl told Smith: ‘We wd. give him [Fry] any place he liked, and any night.’)

Part of the explanation for Fry’s refusal can be found in the number of debates that were organised at Wadham and the high calibre of the college’s speakers. In addition, notwithstanding his many sporting and academic commitments, some of Fry’s time – and money – was being absorbed by a select dining group, the Wadham Olympic Club, which had been revived in December 1892 and immediately enrolled C.B. as one of its eight members. Finally, it should be remembered that, by the early 1890s, the Union was no longer the most prestigious social organisation in Oxford – an honour which had passed to Vincents. As Joseph Wells wrote, in 1892, membership of Vincents was ‘an honour coveted by most undergraduates who regard popularity and social success as important parts of their University life … it is now, and has been, the club for all distinguished athletes and the most popular men from every college – for those, in short, who are supposed to be the most clubbable people of their time.’ No one at Oxford could meet these requirements more convincingly than Fry. Indeed, his pre-eminence in its sporting life was even more marked in his second year than it had been in his first.

As a footballer, Fry was one of the lynchpins of the Oxford team of 1892–93 and played at his favoured position of right-back in the Varsity match at the Queen’s Club. As Clive Ellis has written, ‘The defences on both sides played well, but C.B. was probably the pick of the bunch.’ A late goal by Copley Hewitt earned Oxford a 3-2 victory and gave them a measure of revenge for their heavy defeat the previous year.

In many respects, however, the highlight of Fry’s season came in college, not university, football. Despite having a limited pool of players at his disposal due to Wadham’s comparatively small size, C.B. produced a surprisingly effective side to compete for Oxford’s inter-college Association Cup. Smith, for example, was a novice at the game but Fry turned him into an integral member of the team – telling him ‘he could not be worse than some of our eleven, and would in any case be useful to argue with the referee.’ In due course, helped by C.B.’s coaching, F.E. became an effective centre-half as well.

To everyone’s surprise Fry steered his team into the Cup final, in which his makeshift eleven faced the defending champions, Magdalen, whose side included numerous Blues. Against the odds, Wadham even took the lead and remained in front until 15 minutes from the end: Magdalen then scored twice in 10 minutes to end the underdogs’ chances of causing a major upset. Despite the result, the cup-run had been a triumph for C.B., as a player and a coach. Isis reported that he had been ‘magnificent, both in attack and defence’ and applauded the ‘splendid’ coaching which had produced ‘a wonderful improvement in the team.’ Similarly, Wells wrote that ‘even for the University, Fry probably never played more brilliantly than he did for his College in the Final of the Association Cup.’

As a cricketer, too, C.B. built upon his record as a freshman. In his first match of the season, for the Eleven against Sixteen Freshmen, he proved his worth by hitting 92 – an innings which dwarfed the next highest score. In the following game, against the Next Sixteen, he hit 66 of his team’s 79 runs and took 6-84. Once again, though, C.B.’s fine early season form was followed by a run of comparatively modest scores. Overall, although he registered fewer ducks than in the previous season, he did not have the satisfaction of hitting any centuries either. However, by scoring 36 against the M.C.C., taking 37 from the touring Australian bowlers and registering a half-century against Sussex, Fry showed that he still had the ability to succeed against first-class attacks.

Unfortunately, the game with Cambridge was a far less satisfactory contest than in 1892. Although C.B. had the pleasure of securing his first Varsity match wickets, Cambridge’s modest total (182) proved too much for Oxford. In their reply, only Lionel Palairet produced an innings of substance (32) and his side was dismissed for 106 – with Fry bowled for 7.

When they batted again, Cambridge capitalised on their first innings lead and reached 254 – setting Oxford 331 to win. No one expected them to reach such a high fourth innings target but, equally, few would have predicted such an abject capitulation: the team was dismissed for 64 – and only one batsman, Fry, scored more than 12. Not only did C.B.’s innings of 31 account for almost half his side’s total but it provided an early demonstration of one of the most significant features of his whole cricketing career. As he showed time and again, he had both the mental application and the technical understanding to cope with wickets and attacks which left his team-mates confounded.

The Varsity match brought a miserable end to a grim season for Oxford: they played nine matches and failed to register a single win. Although his performances were unexceptional, Fry had been one of the side’s better players: in the averages, he finished second for bowling and third for batting (but less than two runs an innings behind the top batsman). Once again, it is worth quoting Lillywhite’s verdict on Fry: ‘Played some fine innings, but not thoroughly to be relied on. Did good service on occasion as a bowler. Medium-pace right-hand. Good fielder anywhere.’ In other words, the author was more complimentary about Fry’s bowling and fielding than his batting. In future years he would be given every opportunity to reconsider his assessment.

It was in athletics, not cricket or football, that Fry made the biggest mark during his second year, distinguishing himself in a variety of events. As a sprinter, for example, he had an outstanding season in 1893, recording some highly impressive times and tying with the Oxford president, Alexander Ramsbotham, in the university trials which determined the Varsity match team. Each of the runners thought he had won so, C.B. concluded, ‘The chances are that the judges were right.’ Characteristically, however, Myers claimed, ‘An instantaneous photograph taken of the finish certainly endorses the opinion that Mr Fry was the first to break the worsted.’

In the Varsity match itself, the same runners, Fry and Ramsbotham, represented Oxford against Cambridge in the hundred yards and, once again, crossed the line together in joint first place (in 10.2 seconds). For C.B., dead-heating with his president (and, in the process, beating both Cambridge runners) was a major achievement – and all the more remarkable when one considers Ramsbotham was not only Oxford’s ‘first string’ but the outright winner in 1892 (and joint winner in 1891).

As a hurdler Fry enjoyed less success but it was still an event from which he derived considerable enjoyment. At Repton he had persisted with hurdling despite using a variety of highly unorthodox and often unsuccessful techniques. At one stage he used a right-footed take-off for one hurdle and a left-footed one at the next; he later changed his approach so that he took off and landed using the same foot. Such methods enabled him to clear comparatively low hurdles but, when he faced full-sized ones, their defects became obvious. By the time he reached university, C.B. seems to have adopted a more conventional – and successful – technique and, in 1893, finished a close second to W.J. Oakley in the Oxford trials. It was a good performance, but not enough to win a place as a hurdler in the Varsity match team.12

Despite his disappointment, Fry continued hurdling – although he may have regretted doing so. The great Kent cricketer Percy Chapman recalled an occasion when, as a boy, he had been taken along to watch a country house cricket match in which C.B. was playing. The pavilion enclosure was surrounded by a low white fence and Fry, carrying a tray of tea to some ladies, decided to hurdle it. He cut it too fine, tripped over the top and plunged, inelegantly, to the ground. ‘My first sight of the great athlete,’ commented Chapman, succinctly.

As with his hurdling, Fry produced a good performance as a high jumper at the Oxford trials but, despite recording a personal best of 5 feet 8½ inches, he was not invited to contest the event in the Varsity match itself.

As a long jumper, however, C.B. was in a league of his own and, on 4 March 1893, in the trials, he produced a leap that earned him a place in athletic history. The venue was Oxford University’s athletic ground in Iffley Road and a substantial crowd, including the future England cricket captain, Pelham Warner, and a young schoolboy, Compton Mackenzie, gathered to see the athletes in action. Fry’s prospects, it seemed, were poor. He spiked his big toe but, after completing three practice jumps, considered himself fit enough to compete. It appeared, however, that his difficulties were not over: according to the Oxford Magazine he shortened his stride before one of his leaps, ‘seemed uncertain of his take-off’ and finally jumped ‘three or four inches behind the board’. As C.B. himself recalled:

My last stride before taking off was much shorter than usual, and I seemed to stop dead while you might count me. However, for some reason or other I seemed to develop more spring than usual, and went very high in the air. When I landed in the pit, instead of as usual having to struggle for my balance not to fall back, I simply bounced clean out of the pit, and landed about six feet away on the track.

Writing many years later, one of the spectators13 confirmed that Fry had gone appreciably higher than in his earlier jumps and another, Warner, immediately realised ‘it was obviously a stupendous leap.’ C.B. seemed to agree and, according to an eyewitness, he ‘turned round with a grin, clearly appreciating that he had done something special.’14 The officials went to work and started measuring his jump. The task took several minutes until, amid growing excitement, one of them made the announcement, ‘23 feet 6½ inches – a new world record.’ The crowd’s reaction was ecstatic. In Warner’s words, ‘the shouting and cheering split the sky’ while the Oxford Magazine confirmed, in a more measured language, ‘the enthusiasm was tremendous.’

In fact, C.B.’s jump had equalled, not beaten, the record set by Charles Reber from the United States, two years earlier. Nevertheless, many commentators were happy to give Fry the benefit of the doubt as it was believed that the American and British rules were different – with Reber’s jump having been measured from his last toe-mark rather than the take-off board. On that basis, the Oxford Magazine, for example, regarded C.B. as the most successful long jumper in history and was unstinting in its praise. ‘In Fry,’ it said, ‘we have undoubtedly the best all-round man seen in Oxford for many years.’

Many people hoped C.B. would improve on this performance when he appeared in the Varsity match, at the Queen’s Club, less than two weeks later. He was unable to do so but still leapt over 23 feet to win the event with more than a foot to spare. Together with his performance in the hundred yards, the long jump meant that he played a major role in securing Oxford’s emphatic 7-2 win.

As C.B. had broken the British record in his first year as an undergraduate and equalled the world record in his second, it was disappointing that, in later life, he felt the need to inflate his performances. As we have seen, he was happy to let his friends add a few inches to the first of these two jumps, in 1892, but a far greater amount of exaggeration, distortion and sheer invention has grown up around the second. No aspect of his life has been surrounded by so much confusion and many distinguished cricket-writers have failed to separate fact from fiction. In particular, John Arlott took C.B.’s various accounts at face value. As a result, his works contain an entirely fanciful version of what actually happened. For example, if Arlott is believed, Fry did not merely equal the world record but broke it; he did so not as a second-year student but as a freshman; he did not practise but arrived – formally dressed – when the event was already taking place (and had to change in the groundsman’s hut); his jump would have exceeded 24 feet but for ‘a damaged take-off board [which] compelled him to take off nine inches short of it’; and, most fanciful of all, Arlott stated that C.B. was able to record an official distance of 23 feet 6½ inches after having a hefty lunch, pouring himself a whisky and starting to enjoy a cigar (which he finished once he had ‘broken’ the world record). Every aspect of this account is either wrong or, at best, open to question and although Fry was guilty of grossly embellishing his story and misleading an admirer, Arlott must be held responsible for uncritically believing, repeating and perpetuating an ageing raconteur’s dramatised version of events. Furthermore, Arlott played his part in creating the myth that Fry’s was a particularly long-lasting world record. It was not. In this case, however, other renowned cricket-writers are more culpable for exaggerating C.B.’s performance. For instance, Benny Green stated that Fry created ‘a world record which stood good for the next twenty-one years’; Christopher Martin-Jenkins has extended C.B.’s record-holding reign to 25 years15 and A.A. Thomson claimed that Fry ‘set up a world long-jump record so hard to beat that, while records were being broken right and left almost every year, his remained intact for nearly half a century.’ In reality, the record shared by Fry and Reber was broken by Ireland’s J.J. Mooney on 5 September 1894, so C.B.’s stint as a (joint) world record-holder lasted only 18 months and a day – around 45 years less than Thomson suggested.

Although the stories he told in old age may reduce one’s opinion of Fry’s character, they should not detract from the scale of his achievement as an athlete in the prime of his life. By the end of his second year at university, C.B. had, after all, appeared in county cricket, scored a first-class hundred, secured two successive triple Blues, won an England cap at football and equalled a world athletics record – and he was barely 21 years of age. Fry combined these remarkable sporting achievements with continued academic success. In his second year at Oxford, he secured a First in Classical Moderations, subsequently attributing his success to hard work, a sound grounding in the classics and his sheer love of the subject. According to Life Worth Living:

I possessed what a supercilious Don would estimate as a good sixth-form facility in Latin and Greek composition, especially in writing Latin and Greek verse; and being even then very fond of the ancient classics, I had read a lot of them and was fairly competent in translating at sight. Looking back, I can see that without being up to the standard of University prizes in classics, I was pretty well furnished for my age.

On this occasion, Fry was being uncharacteristically modest. ‘Plum’ Warner later recalled that he had discussed C.B.’s academic ability with his tutor, who informed him that Fry was ‘a really remarkable classic’ who had got a First ‘on his head’. By adding academic achievement to his sporting successes, C.B. strengthened his position as perhaps the most glamorous figure at Oxford and, in May 1893, his pre-eminence was confirmed when Isis chose him as one of its first ‘idols’.

In his third year Fry continued to dominate the university’s sporting life. In addition to representing Oxford at football, athletics and cricket, he added a new string to his bow by enjoying considerable success in college rugby.

C.B. was not entirely new to the game. In April 1892, the Corinthians had issued a challenge to other amateur sports clubs, offering to meet them at football, rugby, cricket and athletics, with the proceeds going to charity. The Barbarians picked up the gauntlet and, four months after receiving his England soccer cap, courtesy of Jackson, Fry was more than happy to represent the club ‘Pa’ had created. C.B. appeared in the first three stages of the contest – in the football, rugby and athletics matches – but not, it seems, in the cricket (the game taking place some weeks later). As expected, he performed well in the athletics competition, winning the long and high jumps and coming a close second in the 100 yards. Similarly, he faced few difficulties in the football match, which the Corinthians won at a canter. In the rugby, however, C.B., despite his inexperience, was a revelation. Playing as a wing three-quarter, he scored one brilliant try and played a key role in creating another. As a result the Corinthians brought off an astonishing triumph, beating the Barbarians at their own game – even though they fielded seven players who had won, or went on to win, international caps.

Some post-match assessments suggested the Barbarians were victims of their own good sportsmanship. At the time rugby referees allowed a game to continue until one side appealed against an infringement by the other. Realising the Corinthians were unfamiliar with, for instance, the off-side rules, the Barbarians were reluctant to appeal too frequently, particularly in the early part of the game. But this was not the only reason for their defeat. Attempting to convert one of their tries, the Barbarians’ kicker hit a post; the same player, Johnston, also missed a penalty and, more generally, the Barbarians had genuine difficulty in coping with the all-round pace of the Corinthians. A history of the Barbarians even suggests the game may have had a lasting impact on the way rugby was played:

No doubt the Corinthians who, at that time, included some fine athletes like C.B. Fry were given a lot of latitude whenever they offended against the complicated rugby rules, but for all that the Corinthians were entitled to the glory that follows a fully substantiated challenge. The totally unexpected victory of the dribblers and chargers over the scrummagers and tacklers was not merely good fun but interesting as sport. It may well be that the success of the fast and powerful Corinthians, forwards as well as backs, led to the speeding up of rugby forward play.16

In 1893–94, C.B.’s experience against the Barbarians proved invaluable as F.E. Smith tried to create an effective college rugby team from the limited resources at his disposal. Although Wadham was a small college, containing only one rugby Blue, Smith moulded players like Fry and Simon into a team that was highly cerebral and every bit as effective, beating every other college in Oxford. Playing as a three-quarter, C.B.’s exceptional pace more than compensated for his technical failings and his early tendency to tackle, in F.E.’s words, ‘like a schoolgirl fainting’.

After their success in Oxford’s inter-college matches Wadham faced the daunting prospect of playing the Cambridge champions, Caius, at Fenner’s. They appeared to have little hope of success against an exceptionally strong side, which included four Blues and two internationals. Yet, in a closely contested and well attended game, Wadham scored the only points, through a try, to emerge triumphant. After a celebratory dinner, Smith’s victorious team returned to Oxford – but rather marred their day’s work by vandalising the railway carriage in which they travelled.

It was on the football pitch that Fry started to fulfil the prediction that he would lead Oxford at three major sports, but his career as the university’s soccer captain endured a controversial start. In a match against the London Caledonians, he was criticised for using an over-aggressive style of play and language that was even stronger. The Scotsman accused him of ‘using his might most unmercifully’ and of ‘singling out for his attentions the lightest and most unoffending man in the team – Peter Hunter.’ It added: ‘His language was disgusting. To call a man a “pig” is surely coming very low down for a Varsity man. To prefix the epithet with a disgusting adjective may be permissable at Oxford, but it is out of place at Caledonian Park. It is only right to say that Fry’s comrades were disgusted at his behaviour.’

In response, Isis defended the man who had been its ‘idol’ only five months earlier and its account contradicted each of the accusations made by the Scotsman. Far from intimidating Hunter, it claimed that Fry had been taunted by him in the hope that he would lose both his temper and his appetite for the contest. It also pointed out that Hunter’s disciplinary record was a poor one and exonerated C.B. from any suggestion that he had used bad language. Its reporter stated that he had interviewed three members of the Oxford side, ‘who all of them say that they never heard any such expression used, and that they were disgusted neither at the behaviour nor the language of the Captain, nor of any other member of their own side.’ He added that Fry himself had denied any wrongdoing and quoted the ‘genial Wadham athlete’ as saying, ‘I am not in the habit of calling people “pigs” at all.’ After all, he added, ‘Oxford isn’t a board school.’

The rest of the season went much more smoothly and C.B.’s team proved one of the strongest in Oxford history. By February 1894, they could approach the Varsity match with confidence. According to Edward Grayson, an expert on amateur football:

the Oxford side arrived at West Kensington under C.B. Fry’s captaincy as strong favourites for the game. The defence contained the current or future England internationals, G.B. Raikes, W.J. Oakley and Fry, a strong Carthusian half-back line, and G.O. [Smith] was at centre-forward. They had a record of 14 wins, 2 draws, 1 defeat, with 74 goals scored and 8 conceded. Cambridge, with only one future international, L.V. Lodge, at left-half, had won 12 games, lost 9 and scored only 56 goals as against 38 [conceded]. Oxford, therefore, had the pull all round on paper.

In footballing parlance the match was not, of course, played on paper. Unfortunately for Oxford, it wasn’t played on a proper grassy surface either – the team arriving at the Queen’s Club to find an icy and frost-bound pitch. Before the game was due to begin, the referee approached the captains and asked whether they wanted to postpone it or press on regardless. The Cambridge skipper was content for the match to take place without delay, believing the conditions would reduce Oxford’s advantage. After some hesitation, Fry agreed. As he later admitted, his decision was influenced by the fact that both he and his fellow full-back, Oakley, would be closely involved in the Varsity athletics contest barely three weeks later; any postponement of the football match would have disrupted their preparations. Above all, though, C.B. believed Oxford were simply too good to lose.

Fry’s confidence appeared well-founded, his side taking the lead in the first-half. From the re-start, however, Cambridge equalised and adapted to the conditions far better than their opponents. Time after time, Oxford squandered their chances by over-elaboration in front of goal when, in the circumstances, a more rudimentary approach was needed. The team’s defenders played better than the out-field players and, according to the Oxford Magazine, ‘Fry, despite some mistakes and an inclination to kick out when he should have kicked to his forwards, worked hard’. Despite his best efforts, Cambridge scored two further goals to secure a shock 3-1 win. ‘I made the mistake of agreeing to play,’ C.B. later wrote, ‘and probably the best side that ever represented Oxford at Association football got beaten, and, what is more, on the play of the day, on its merits.’

Having attached such importance to the Varsity athletics contest, Fry would have looked particularly foolish if he had led Oxford to defeat in that too. Fortunately, Oxford won decisively, 6-3, although his own performances were less majestic than in the previous year. In the hundred yards he began impressively but made an elementary mistake as the race neared its end. As Myers explained:

Fry got a big start, and seemed certain to win. When nearing home it occurred to him to wonder what had become of Jordan. ‘In that brief flash of inattention,’ he remarks, ‘though I did not look round or consciously relax my pace, the whole field passed me, and I finished last. A man to sprint his fastest must glue his mind to the effort of reaching the tape; if he relaxes his will for a moment he automatically slackens his pace.’

C.B. had been right to worry about Jordan: he was Oxford’s ‘first string’ and his victory in 1894 was the first of a hat-trick of Varsity match successes. But it was clearly wrong and entirely out-of-character for Fry to let his attention stray from the task in hand.

In the long jump, too, Fry’s performance appears to have been slightly disappointing. Although he won the event for the third year in succession, his winning jump was well over a foot shorter than his personal best and the margin of victory was only four inches. However, as C.B. was carrying a painful heel injury, his jumping was far more impressive than these statistics suggest.

In many respects the highlight of Fry’s presidency of the Athletics Club came four months after the Varsity match, when he led his team in the first contest between universities from different countries. Around 5,000 spectators were attracted to the Queen’s Club to see Britain’s standard-bearer, Oxford, tackle the mighty Yale team from the United States. As the event was held in mid-July, at the end of the university’s cricket season (when he was trying to secure a place in the Sussex side), C.B. was short of practice in the long jump (and still suffering from an injured heel). He performed accordingly. In Myers’ words, ‘Fry’s first try was no good, his next was 22 feet ¾ in, and his third 21 feet 9 inches. In his fourth, just as he felt he was going to make a good jump, the board split under his spikes and he went a terrific header into the sawdust.’ C.B. was duly beaten into third place, finishing 10 inches behind the victor from Yale.

Having come third in his best event, C.B. could hardly have expected to fare much better in the 100 yards but he treated the crowd to a exceptional performance. Running into a head-wind, he took his customary early lead and was soon a yard in front of the field. For the first 70 yards, he remained comfortably ahead but then faced a stern challenge from Jordan. His advantage was steadily eroded but when he crossed the line, in 10.4 seconds, he was still about a foot in front of the Varsity match champion. It was, he later said, the best run of his life – and one which helped Oxford to an historic win by 5½ points to 3½.

As a Reptonian C.B. had dreamt of being hailed ‘Captain of Varsity Soccer, President of Varsity Athletics, and Captain of Varsity Cricket’ and, between facing Cambridge and Yale at athletics, he succeeded Lionel Palairet as the skipper of Oxford’s cricket team, making the dream come true. Despite his experience of cricket captaincy at Repton, the Oxford Magazine was lukewarm about his prospects, hoping that he would ‘make up in keenness what he lacks in knowledge of the game.’ In one sense its words were prophetic: Oxford struggled all season and excelled only as a fielding side, with Mordaunt, Leveson Gower and Fry regarded as ‘outstanding’.17

As a batsman and bowler C.B. struggled early on. Even when he performed better, hitting 75 against Somerset, he found himself completely outshone by Lionel Palairet, who hit 181 for the county against his former university colleagues. But far from signifying a return to form, C.B.’s encouraging performance was followed by a series of depressingly low scores: in two matches (and four innings) against Lancashire he managed just 6 runs, and he made only 5 and 6 against the M.C.C. Despite these poor scores, he insisted there was nothing wrong with his play and the solution to his problems proved remarkably simple:

The strange part of it was I was in first-rate form, and could play splendid innings in the nets. However, nothing went right in matches. I could not get a bat I liked; you never can when you are not making runs. Just before we started from Oxford to play our out-matches, old Petty, the head of the ground staff, gave me a bat which he declared was a beauty. It was a Warsopp, of good grain, but much too heavy for me. The first time I tried it I made a century, at Hove against Sussex.

In fact, Fry made a mere 7 in Oxford’s first innings but, in the second, he came to the crease with his side struggling at 56-3 and proceeded to hit an impressive, and chanceless, 119.

In Oxford’s next match, against the M.C.C., Fry failed to maintain his momentum as a batsman but the Warsopp still seemed to have changed his luck. In addition to dismissing Ranjitsinhji (first ball) and Jackson, he came extremely close to taking a hat-trick – bowling Timothy O’Brien and Charles Wright with successive deliveries and appearing to take another wicket with the next. However, to the surprise of the fielders, and the frustration of Fry, the umpire decided one of the bails had been removed by either the wind or the wicket-keeper and allowed the batsman – Arthur Heath – to continue his innings.

Despite C.B.’s partial return to form Oxford were still unable to win any matches and approached the Varsity match, at the start of July, without a victory under their belts. For Fry, the position could hardly have been more different to his experience as the captain of the soccer side, which had confidently looked forward to the match against Cambridge. Nevertheless, despite the surprising defeat of his football team, he was convinced that his cricket eleven – which was, by any standards, far weaker – would defeat Cambridge at Lord’s.

In sharp contrast to his two previous Varsity matches, C.B. went out to bat when Oxford had made a solid start, thanks to the efforts of Richard Palairet, ‘Harry’ Foster and Gerald Mordaunt. But, using his new Warsopp, Fry found it difficult to get going. Trying to compensate for their comparatively weak bowling attack, Cambridge made every effort to deny him the leg-side deliveries he craved. Their tactics were sometimes taken to the extreme – and they conceded a number of wides outside the off-stump – but the ploy appeared to work and C.B. was barracked by the crowd as he struggled to get off the mark. Weaker characters might have buckled but, after half an hour, he finally scored his first run. At the other end Francis Phillips was playing with greater freedom and, despite Fry’s slow start, they added 137 in 100 minutes – with Phillips scoring 78. After his dismissal, only one other batsman (George Raikes) reached double figures and C.B. found himself in the 80s when the last batsman, Richard Lewis, came in. Although Lewis was a highly capable wicket-keeper, his batting left a great deal to be desired. (The best that Lillywhite’s could say was, ‘As a bat, backs up well.’) Both batsmen realised if Fry was to score his century, it was Lewis’s turn to stonewall and time for C.B. to hit out:

it was touch and go for three figures, because when I was 84 our last man, the Winchester wicket-keeper, R.P. Lewis, came in white in the face. I was at the other end when he took guard, and he then walked down the wicket and whispered hoarsely, ‘Charles, I won’t get out’. He did not get out that over. He kept his bat plugged in his block-hole and scarcely moved it to greet the balls he did not leave alone. I knew the next over was my only chance, so I gambled and carted four straight balls to the square leg boundary. The first ball of the next over Lewis lifted his bat from the block-hole and was bowled all over his wicket.

Although Fry did score his century, and Lewis was bowled for a duck, the reality was rather different – and a little less dramatic. As Lewis had arrived when Fry was on 83, not 84, C.B. could not have reached his hundred with four successive on-side boundaries, as he claimed. In fact, he scored his remaining 17 runs in two overs, not one, and hit at least one of his boundaries to the other side of the wicket – Myers referring to ‘a lofty four on the off’.

Even though he had scored an undefeated century, and become only the ninth Oxford centurion in the Varsity match’s 67-year history, Fry’s performance was not without its critics. Numerous spectators felt that he should have batted more positively during the first part of his innings and not confined his aggression to the short period after Lewis’s arrival. Some cricket-writers agreed: Sir Home Gordon wrote that C.B.’s ‘century in the Varsity match was a poor one’ and, many years later, when he gave a large dinner to celebrate watching his fiftieth Varsity cricket match, he remarked that the worst century he had seen was ‘the stiff one made by Charles Fry’. As C.B. was a guest, it was hardly the most diplomatic comment but one which he happily endorsed.

At the time, though, his contribution was judged, first and foremost, on its effectiveness, not its elegance. Cricket described it as ‘an innings of inestimable value to the side’ which, by steering Oxford to 338, put his team in a strong position. But Fry’s innings should also be seen in the context of his wider sporting achievements. C.B. was not, after all, someone who had devoted his entire time or attention to batsmanship. He had also excelled as a footballer and athlete, and becoming a centurion at Lord’s, in one of the most important fixtures of the season, was an extraordinary achievement to add to those he had recorded in other sports. According to Joseph Wells, Fry’s century was simply ‘the crowning success of the most brilliant athletic year which has ever fallen to the lot of an undergraduate’ and even Punch joined in the praise for C.B.’s latest accomplishment.18

The rest of the match was satisfying for Oxford but comparatively uneventful for the crowd. Cambridge reached 222 in their first innings and, following on, were dismissed for 200 in their second – setting Oxford only 85 to win. C.B., who had batted at Number Five in the first innings, was not needed as his side strolled to 88-2 and a comprehensive eight-wicket triumph. Their first and only victory of the season had come in the game they most wanted to win and Fry had done more than anyone to bring it about. As well as scoring an undefeated hundred, he had fielded particularly well and captained his team impeccably. According to the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News: ‘Fry’s captaincy was an important factor in the victory. He seemed to know the very moment a change in the bowling was required, and used great judgement in placing the field. He was certainly the hero of the match.’

For Fry, the Varsity game was undoubtedly the highlight of his Oxford season. By his own high standards his overall performances had been mediocre. He finished sixth in the bowling table and, although he occupied second place in the batting averages, he would have been disappointed to average barely 30. Later in the summer, however, C.B. had the satisfaction of making his first appearances for Sussex and scoring his maiden century (109) for the county in an eventful match19 against Gloucestershire – led by W.G. Grace.

In view of his all-round achievements, it is hardly surprising that Fry became one of the most dominant figures at Oxford. Although Wadham included several other men of extraordinary talent, C.B. was easily the most impressive, glamorous and highly acclaimed member of the newly resurgent college. During his four-year stay, it was often referred to as ‘Fry’s College’ and, as the saying went, it consisted of ‘Fry and small fry’. In addition, he was often nicknamed ‘Almighty’ and received parcels simply addressed to ‘Lord Oxford’. While one has to question whether, as Smith claimed, ‘even Heads of Houses and Vice-Chancellors used to bow to him [C.B.] in the street’, F.E. would have been acutely aware that his own reputation, despite his mastery in the Union, almost paled into insignificance beside that of Fry. Several of their contemporaries have provided ample confirmation that C.B. far outshone Smith and was not only the most celebrated undergraduate at Wadham but probably the most highly regarded man in Oxford as a whole. For example, the artist William Rothenstein, who spent much of 1893 at the university, wrote: ‘At Wadham, as at Balliol, there was a brilliant group of men – C.B. Fry, F.E. Smith, John Simon and F.W. Hirst. Of these C.B. Fry had then the widest reputation in Oxford. Extremely handsome, a triple blue, a good scholar, with a frank, unassuming nature, small wonder he was a popular hero. After him F.E. Smith played second fiddle.’

Hirst agreed, while a student at Worcester College, Keble Howard – who later influenced C.B.’s career – provided an invaluable summary of the most widely admired figures in contemporary Oxford. ‘The chief heroes of my day,’ he wrote, ‘were C.B. Fry, J.A. Simon, F.E. Smith, Hilaire Belloc, Paul Rubens, James Hearn and the brothers Palairet [but] Fry was easily the biggest celebrity of all.’

Fry’s status ensured that he came into contact with those whose fame was already spreading far beyond Oxford. For example, early in his university career he was invited to meet Max Beerbohm, the writer and caricaturist, who ‘immediately endowed my new world with a sense of literature and art and the science of life.’ Through Beerbohm he met Rothenstein, who was preparing a book of drawings of Oxford characters and decided to begin with Fry. The two men became friends and, as Rothenstein’s circle included Belloc, it is likely that Fry saw more of him than he disclosed in Life Worth Living, in which he confined himself to praising Belloc’s brilliance in the Union. Furthermore, as Beerbohm knew Oscar Wilde, and both Rothenstein and Beerbohm were friends of Lord Alfred Douglas, it is possible that Fry could have been introduced to Wilde on one of his regular visits to Oxford. If they did meet, it was not something that C.B. chose to mention in his highly selective autobiography. It is certain, however, that, towards the end of his university career, Fry was one of only half-a-dozen students who were invited to have breakfast with Cecil Rhodes at his old college, Oriel. The fact that C.B. was included in such an elite group showed the high regard in which he was held in the Oxford of the mid-1890s.

Fry’s position in Oxford society was further strengthened by his membership of the Wadham Olympic Club, which attracted distinguished guests from other colleges. C.B. gave the Club a particularly elitist air by reviving the custom of dining in evening dress and commissioning a special waistcoat which, according to the minutes, was ‘to be made of Wadham blue cashmere with three brass buttons engraved with the Club monogram’. His presence did much to make the Club’s meetings some of the most prestigious gatherings anywhere in the university and Smith, who joined later, confirmed that membership was a way of entering the most fashionable circles that Oxford had to offer. C.B.’s guests showed the circles in which he was moving: they included William Rothenstein, Copley Hewitt and Malcolm Seton, a large, scholarly and pleasant man (and friend of Belloc), who was eventually knighted despite his youthful belief in republicanism.

All this helped to ensure that C.B. became a nationally known figure. For example, Rothenstein’s book Oxford Characters, published in 1893, informed its readers that Fry was ‘the most brilliant and universal of Oxford athletes’. The drawing itself, though, was not a complete success. One of Rothenstein’s biographers (Albert Rutherston) has written that C.B. looked ‘rather like a giant St Christopher’ and Fry himself complained that it made him look like ‘a coal-heaver’.

Through one of his other friends C.B. was also featured on the pages of The Idler although, once again, the results were not, from C.B.’s perspective, particularly successful. The article was written by Beerbohm, who had gone to interview Fry in his rooms at Wadham one Sunday morning:

‘Where,’ I asked of the porter, ‘are Mr Fry’s rooms?’

‘Fry,’ he said slowly, ‘which Fry do you mean? What initials?’

Was there, then, more than one Fry? T, H, E were the only initials I had ever supposed the great athlete to possess, but it appeared that he was known officially as Mr C.B. Fry.

Steep and tortuous, and of a darkness peculiar to their kind, were the stairs, leading up to Mr Fry’s ‘two-pair front, first quad’; nor, when I knocked at the door, came any answer; nor, when I opened it, was anyone in the room. But the clock on the mantelpiece showed that it was the hour appointed, 11am; the table was laid for breakfast, and down by the fire something under a cover was keeping as warm as it could; all of which portents prepared me for the apology that was shouted from the other side of the bedroom door, and the loud splashing and stamping as of one taking a cold tub.

I stood on the hearthrug and took a look round. A regular college room it was, rather dark under its low ceiling and beautifully panelled with oak. Engravings of the academic kind – little boys with apples and little girls with pears – mingled with drawings by younger artists and many photographs of the football and cricket teams, and all the other bodies adorned by the gentleman in the next room. It was evident that he was a smoker, for there were pipes all over the room. It was very nice and comfortable, however, and on the breakfast table the scout had arranged a neat pile of letters. Were they applications for autographs or begging letters from unsuccessful athletes?

In The Man and His Methods, Fry appeared to admit that he had got up late, saying he tended to go to chapel in the evening, not the morning. But by the time Life Worth Living appeared, C.B. seems to have become more sensitive about his time-keeping – claiming the interview had taken place at tea-time and dismissing the suggestion that he had been interrupted in the middle of a bath. However, his main objection was that, according to Beerbohm, he had dismissed golf as ‘glorified crocquet’, a charge he was keen to deny. In his autobiography, he insisted: ‘Such a phrase was beyond me at that age, and I had never played golf, and Max had never mentioned the subject; but he thereby succeeded in earning me a wide unpopularity.’