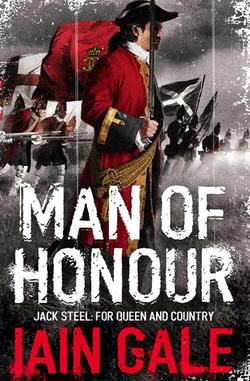

Читать книгу Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms - Iain Gale, Iain Gale - Страница 12

ОглавлениеTHREE

Saluting the sentry posted outside, Colonel Hawkins walked through the shade of the striped entrance awning and into Marlborough’s tent. Inside the General Staff stood gathered in silence around their Commander-in-Chief. It was gloomy and unpleasantly humid, the airless atmosphere adding to the inescapable tension of what had evidently been a difficult briefing. Major-General Withers, Goors’ deputy, now promoted to command of the Advance Guard, was rubbing nervously at his lapel. Beside him, staring intently at a map stood Henry Lumley, commander of the English horse. Marlborough’s own brother Charles, who commanded twenty-four battalions, the bulk of the army, stood talking quietly to Lord Orkney, while in a corner of the tent, on a folding camp chair, sat the Margrave of Baden, his foot bandaged from the wound to his toe he had received at Schellenberg, with his own half-dozen commanders. Marlborough turned to greet the Colonel:

‘Ah, Hawkins. Have you any news for us? Do the cannon arrive, at last?’

Hawkins shook his head.

‘I am sorry to report, Your Grace, gentlemen, that we have no intelligence save that our last action very much disheartened the enemy. There is of course the important matter of victualling the army. For while our German friends’, he smiled at Baden, ‘will certainly march on with empty bellies, the British soldier I am afraid will not do without his bread. But I can report that we now have the matter in hand.’

Hawkins lowered his voice.

‘There is another matter, Your Grace. That rather delicate matter of which we have spoken before and on which I must speak to you now in person.’

Marlborough nodded to Hawkins and addressed the company:

‘Well, gentlemen. That it would seem is that. We are in agreement then. There is no other course of action. And as regards the more pressing matter of the attack on the town of Rain, you are all clear as to your duties?’

The British commanders nodded and quickly took their leave. Baden, it seemed for a moment to Marlborough, might be about to make yet another protest. But then, as if by some miracle, his face grew ashen-white and he closed his eyes. Clearly his wound was giving him considerable pain. Reopening his eyes and leaning on one of his commanders for support, he rose from the chair and with a hasty goodbye left the tent.

Marlborough relaxed and leant back against the table.

Only Hawkins now remained in the tent, along with a single servant clearing away the remains of the hasty breakfast which had preceded their meeting. Marlborough spoke.

‘So then, James. I take it that you have informed the officer in question of his mission?’

‘Lieutenant Steel, Sir. Yes, he is now fully apprised of what he must do.’

‘Good. And you truly think that he can do it, James?’

‘I am in no doubt, Sir. I’ve seen him fight. He is, I am convinced, one of the finest officers in your army.’

‘He is something of an individual, I believe.’

‘He transferred to Farquharson’s from the Guards, his commission into that regiment having been purchased for him by a lady. He’s of modest stock, Sir. The second son of a Scots farmer. He has no private income to speak of and he is hungry for patronage and promotion. An ideal man for the job.’

Marlborough toyed with a silver snuff box which lay on the table, opening and closing the lid.

‘He is over-familiar with the men. Is that right?’

‘I would not have put it quite that way, myself. Although he is perhaps more ready to take the advice of his Sergeant and he shares Your Grace’s own concern for the welfare of his soldiers. “Eccentric” they call him in the officers’ mess. But the men, and those who have served with him before, say that there are few better than Steel in all your army. And make no mistake, he’s a shrewd one, Sir, and a wit. As you will recall, it was your own lady who recommended him to us.’

‘That, as you know, James, is quite beside the point. It is my decision to employ Mister Steel in this matter and mine alone. My dear wife must be kept quite apart from the whole affair. For, should he fail in his mission. Should, God forfend, those who wish me ill get hold of that paper, the Duchess must not be implicated in the slightest degree.’

Hawkins sensed that it would be politic to change the subject. He looked up at the map, running his hand across the black squares which represented the towns and villages of the Electorate, which he knew might soon be nothing more than smouldering ruins.

‘You are quite set on laying waste to Bavaria?’

Marlborough looked down and tapped the red velvet-covered baton – the symbol of his rank – on the small, polished oak table which had been placed against the wall of the tent.

‘I shall dispatch men from this army to burn as many of the towns and villages of Bavaria as we find within reach. Just the houses mind you. We shall spare the woodlands and of course leave anything of the Elector’s property. Seeing that still standing can surely only help to turn his own people against him. And the people themselves shall be safe, I will not have any of them harmed. It is mere coercion, not rape, but it is the only way. We must force the Elector’s hand. It is of particular sadness to me in a country of such neat domestic husbandry as I have ever seen outside England.’

Hawkins shook his head. ‘If you are set on it, then I cannot divert your mind. But this is not warfare as you and I have known it these past twenty years. And if you really want to know my opinion it will not have the effect you believe. The Elector will not turn, whatever you do to his country. And be careful, Your Grace. I know soldiers as well as you do. For all your care of this army, Sir, it is still made up to a large extent of brigands and cut-throats. We shall have to keep a watch on them.’

Sensing how sombre the mood in the tent had now become, Hawkins added with a smile: ‘For I know how you hate anything that is not properly accounted for.’

Marlborough laughed. From outside the tent, above the general hubbub, they caught the sound of the drums and fifes of a regimental band striking up to keep the men in good spirits. ‘Lillibulero’. Marlborough smiled and began to drum his fingers on the table top. It was a favourite tune.

‘You still know how to divert me from my black moods, James. Thank God at least for that. But I am so tired. More tired, my friend than I can possibly remember.’ He rubbed hard at his forehead. Pressed his temples together.

‘My entire head aches to bursting. My blood is so terribly heated. I think that I shall call for the physician, presently. Did you know that I have had rhubarb and liquorice sent across from England. The Queen herself advised its use to Lady Sarah as a cure for the headache. But, even so, I am not fully persuaded. I am certain that by this evening I shall yet again be compelled to take some quinine. And you know how sick of the stomach that makes me. But even quinine cannot cure what really ails me.’

He looked into Hawkins’ eyes with a child’s gaze of hopeless yearning.

‘You know to what I refer. All my troubles, James. What times have come upon me. And who now remains with me in whom to place my trust? Poor Goors is dead. He, you know, was my chief help in moments such as this. Others too are gone. Tell me who, save you, old friend, who can I now turn to?’

Hawkins placed a gentle hand upon his Commander’s shoulder. ‘Do not despair, Sir. You are merely unsettled by your headaches. There is hope. As you say, you yet have me. And there is George Cadogan, Your Grace. He has ever been true. And Cardonell too.’

‘True, James. Quite true. Cadogan and Cardonell are a constant strength. Yet that is the measure of it. Just so. Two men and yourself, James. That is the sum of my family. How can I know who else to trust? How to know where my enemies may have placed their spies? God, how I long for this business to be over.’

Removing his wig to reveal his closely cropped hair, Marlborough draped it carefully over the stand made for the purpose that stood with his other personal effects on a small console table in the corner of the tent next to his camp-bed. Then he sat down at the table and, resting his elbows on its surface, buried his head in his hands.

Hawkins stared down at him and wondered at the vulnerability of this man in whom the nation, indeed half the civilized world had placed all its hope and trust.

Presently, the Duke raised his face and, pressing his hands, palms down hard against the table, flat on the polished wood, looked directly up at Hawkins.

‘We must prevail, James. We must beat the French.’

He paused in the epic silence of his words, knowing that, even with his old friend he must instantly dispel any suspicion that they might not be able to do so. Marlborough continued:

‘Oh yes, we shall beat them. That I do firmly believe. But first, I pray to God in heaven that your man Steel will be able to deliver me from the greater personal peril. Or else, truly James, we shall all of us be lost beyond redemption.’

Steel sat in the small tent and carefully inscribed the names of his dead men in the company roster with a neat, tutored script. His soldier-servant, Nate Thomas, sat just within the door flap polishing his master’s boots.

Nate liked Mister Steel. Cared for him more than most of the officers in this army in which any gentleman might purchase a command but where precious few officers were gentlemen. Steel he knew to be a fair man. A man who, if he was cool at times, would always give reward where it was due. And he was a real soldier too. Not some trumped-up popinjay like so many of those who took it upon themselves to give commands. All the same, thought Nate, as he spat on the toe of Steel’s boot before buffing it again, best to give him a proper shine today. For whatever might be Steel’s odd habits, and although he was inclined to behave more like a sergeant at times, Nate knew that he must not have his officer looking untidy on battalion parade. He spat again and began to rub the polish into the leather with a round, even motion, decreasing the size of the circles to produce a glass-like finish. He was staring proudly at his handiwork when Henry Hansam appeared in the entrance. He looked down at the soldier-servant.

‘Hard at it, Nate? Making a good job of it. In truth, though, I shouldn’t bother if I were you. You know that Mister Steel will have them filthy again two minutes after you’ve finished.’

He turned to his friend. ‘Jack. We have a new travelling companion. Allow me to present Lieutenant Thomas Williams, lately arrived from England to join the regiment. More specifically to join our own company. I give you, our new Ensign.’

With a theatrical flourish, Hansam stepped into the two-man tent, holding open the flap so that his companion might enter. The newcomer was a young officer of perhaps 16 years old, with that distinctive, wiry build that came with the starvation diet prescribed by one of England’s finest private schools and a complexion that most readily reminded Steel of ripe strawberries. What most marked Williams out however, was the even brighter hue of his new scarlet coat, as yet unblemished to the drab brick-red worn by the other officers and men of the army, dulled by the dust and mud of campaigning. His crossbelt was whitened to perfection, his cross-plate, sword hilt and scabbard shone fresh from the foundry and his hair was hidden beneath the rich locks of a clean, new full-bottomed chestnut-brown wig that must have cost the best part of a sergeant’s annual pay. In short, thought Steel, the boy was perfect cannon fodder.

Steel smiled and rose to greet the new arrival.

‘Mister Williams. Or might I say Thomas? Or perhaps you prefer Tom? You must know at once, Tom, that we stand on no great formality in this company.’

‘Thank you, Sir. My parents do call me Thomas, but you may call me Tom, if you wish, Sir.’

He was touched by this unusual officer’s apparent interest, and surprised. It was one of the rare instances he had found since his arrival in this army of what just might prove to be real friendship.

The younger son of a gentleman farmer from Wiltshire, Thomas Williams, with his lack of ability to absorb either the classics or the Bible and his tendency to colour and stutter when the centre of attention, had seemed from the first an unlikely candidate for the church and so his father had purchased him a commission in Farquharson’s Foot. Perhaps in a couple of years’ time, if Thomas acquitted himself well, Mr Williams senior would find the additional £300 to raise his son to a full Lieutenancy. Perhaps the army might be the making of him. For the present, however, Tom found himself on the lowest rung of the officer hierarchy and his new comrades had lost no time in letting him know it. Here though, in this curious-looking, strikingly handsome Lieutenant of Grenadiers, with his strange clothes and the unorthodox hair, Thomas Williams sensed that he might have found a kindred spirit, or perhaps at least a guardian angel. He realized that Steel was looking at him very closely.

‘Have we met?’

Steel stared hard at Williams’ eyes. Looked at the long slant of his nose, the slightly weak chin and tried to place him. Eventually it came. ‘Yes. I believe we have. I do know you now. You were with Jennings. At the tavern.’

The boy blushed and looked down at his gleaming shoes. Grasping nervously at his sword knot, Tom said nothing. Then thought the better of it:

‘I wasn’t exactly “with” Major Jennings, Sir.’

Steel smiled. Perhaps he had underestimated the lad after all. He knew how defend himself in an impossible position.

‘Yes. That’s good. Well said. And I assume, Tom, that, even if you were not “with him”, you knew better than to believe any of his arrogant twaddle?’

Williams looked up, uncertain as to how to take this or how to respond. Was it yet another example of the sort of mess-hall ribaldry to which he was fast becoming accustomed? Were they trying to make him appear a fool yet again, as he had so often been caught out at Eton and only recently, on his first week in the army when a sergeant-major at the depot in England had quite deliberately put him out of step when on parade.

‘I … I don’t quite understand, Sir. I thought that Major Jennings was considered a hero. He said that …’

Steel exclaimed and cut in: ‘You will hear Major Jennings say many things, Tom. And I dare say it is possible that some of them may well be true. So, if you choose to believe that he is the perfect martial hero he would have you think him, then you must consider that is precisely what our Major Jennings is. He is a hero as drawn on stage by the great Colley Cibber himself, or Sir John Vanbrugh. As perfect a hero as you or I might be likely to see treading the boards at Drury Lane or Dorset Fields on any night of the week, for two shillings.’

Williams frowned.

Hansam chuckled. ‘Now, Jack. Don’t tease the lad.’

Steel nodded. ‘I was forgetting myself. Hero or not, Tom, Major Jennings is a soldier nevertheless, and he will march with us and serve with us beneath the colours and he will stand with us before the shot on the field of battle and take his chances against the French just as we do.’

At the mention of battle Williams turned pale, then smiled, wanly. Steel, noticing his apprehension, attempted to ease the moment by pretending to brush something off his coat.

‘Wait. There. Restored to glory. And there is more to soldiering than battle, eh Henry? What think you to the army, Tom?’

‘I … I think it must be a very grand life, Sir. I think … that I shall very much like being a soldier.’

Both the Lieutenants laughed. Steel clapped Williams on the back.

‘And I think that perhaps I’ll ask you that question again shortly after your first battle. Then we’ll see how you reply, Tom, eh? Now, come. Time presses. Permit us to stand you a dish of tea, or something stronger if you will, in what passes for the present for our mess. Nate. My boots.’

After Steel had pulled on the shining boots and finished adjusting the other elements of his dress, the three men walked out of the tent. Before them, reflecting the pale sunshine, lay a mass of similar white tents, laid out in symmetrical lines and grids: the entire British army encamped under canvas in its temporary home. It was as if, Steel thought, a small English town had been transported to the heart of Bavaria. Along the alleyways that ran between the rows of tents bewigged officers strolled in conversation while among them dozens of children – the offspring of camp followers – ran and played, sometimes pursued by their desperate mothers. Other women sat nursing babies or were busy washing and steaming the lice-infested clothes of husbands and families or cooking suspicious-looking rations in great iron pots. Soldiers sat beside their tents darning their uniforms and attending to minor wounds and the blisters and sores which inevitably followed from a long march. In separate lines, tradesmen and craftspeople sat before their own tents making good the accoutrements required to keep 30,000 men in a battle-ready state. And with this vision of industry and idleness came the unmistakable noise and aroma of camp life. The staccato clack of metal on metal, the whinnying of the horses, the shrieks of the children, sharp against an undercurrent of chatter and music and rising above it all the not altogether unpleasant stench of food, sweat, horses and humanity. Steel watched as carts filled with provisions rumbled past the lines while others standing ready for the wounded from whatever battle was next to come, were cleaned as best they could by the sutlers of the blood and gore left by their previous unfortunate occupants.

It was a scene being enacted throughout the south German states that morning, and across the French border, Steel knew, in the camp of every army: British, French, Hanoverian, Prussian, Bavarian and the rest. But here, he thought, something was subtly different. Here, he knew that before the tent lines had been laid, the site had been carefully chosen by keen-eyed civilian commissaries sent out by Marlborough himself. And close behind them followed the army: always setting off early in the morning, at sunrise – five o’clock or before – and halting shortly after midday, thus avoiding the greatest heat and making camp so that the night’s rest gave the men the illusion of a full day’s halt. Such was the care that the General took with his army, thought Steel. He knew too that the food and provisions now so evidently on display had been carefully stockpiled to provide for just such an encampment.

This was the new army. Marlborough’s army. An army that made the old sweats mutter in amazement. For here was organization of a type never before seen in a British army on foreign soil. It was Marlborough who had made this army. Had fashioned it from the ragtag rabble that had emerged from the chaos of King William’s Glorious Revolution and brought it through the Irish wars to this great campaign. It was true that back in London, the Duke still had his enemies who even now might be plotting his removal. But here on the march, with the army, ‘Corporal John’ was God. But he was also a soldier and a man, his vulnerable mortality no different from any who filled the ranks of his army. That was the reason the soldiers would fight for him. Would die for him – a hero’s death if they were lucky. That was why they would march wherever he took them. To whatever lay over the next hill. To glory. And so, as the women cooked and sewed and the money changed hands, and the children played and the wounded died, the majority of the soldiers wondered how long they might count on being able to rest and how many more dawns they might see.

Hansam broke Steel’s reverie. ‘I see that we have our Prussian friends with us now.’

Steel too had noticed the arrival of the long marching column as it snaked its way past the lines of the British encampment. The distinctive dark blue coats of the Hanoverian and Prussian infantry, their tall Grenadiers evident in their own profusion of elegant, elaborately laced caps. These were their allies, marching to join Marlborough’s red caterpillar. There must be, he supposed, several thousand of them. Perhaps ten battalions.

Hansam spoke again: ‘You can’t help admiring their style. Can you?’

Steel gazed across at the Prussian infantry, marching in precise formation, using the recently reintroduced, artificially high ‘cadence’ step, looking for all the world as if they were on parade at Potsdam.

‘Style, Henry? That’s not style. That’s nothing more than blind obedience. Those men are more terrified of their own officers than they are of the French. Beaten regularly twice a week for the most trivial offence, they’re underfed and generally abused. They march nicely and I dare say they fight well – to command. But in truth they’re no more than walking muskets.’

Steel was no admirer of the Prussian system. Oh, he had seen it work in battle. Had watched the blue-coated juggernaut as it inched across the field through a hail of shot to smash its way through the enemy ranks. But he could not believe that this was really the way to fight. Like automatons. Certainly you must have discipline and drill. That was the only way to persuade the men to stand in rank and take the shot when it came flying towards them. How else would men stand, save by drill and discipline. And musketry too required drill. That in truth was the real secret of the system of platoon fire that had wrought such destruction on the French in the late engagement. But Steel believed, too, that in the heat of battle there was still a time to give every man his head. Then you really saw what the British infantryman was made of. Certainly, the Prussians were no cowards. But driven on by their blind rote, they could never match the individual skill and ingenuity of a British Grenadier.

Nevertheless, there were, he knew, times when strict discipline was paramount. And now, he remembered, was just one such moment. Steel heard the clock in the nearby village church striking eight. Normally this would have been the time of the morning for the men of his company and indeed the entire battalion to have been engaged in their various routine duties. Sharpening bayonets at the farrier’s wheel, oiling the mechanisms of the highly prized new muskets, checking their shoes and feet for signs of wear. But he knew that none of his men, nor any of Sir James Farquharson’s Regiment of Foot had been among the redcoats sitting in the tent lines. This morning Farquharson’s men had other business on their minds. Only the camp followers and children were excused from this parade. It was, he supposed, an entertainment of sorts. A diversion intended to enhance the moral welfare of the other ranks and to reinforce the position of the officers by example. A flogging. Steel turned to the Ensign.

‘Well, Tom, you’ve certainly chosen your day to arrive. We’ve a spectacle for you. Although I am not sure how well you’ll take to it. But first, come and meet your fellow officers.’

They approached the group of captains and lieutenants who were talking together before the mess tent at one side of the small headquarters square formed by the administrative tents of the regiment. Steel introduced Williams to each in turn.

‘Gentlemen, may I present Mister Williams. Ensign Tom Williams. Newly arrived to the Grenadiers. Tom, may I introduce Monsieur le Lieutenant Daniel Laurent, our own Huguenot “refugie”, who thinks it better to fight for us and his God than his own countrymen and theirs.’

The tall Frenchman bowed, aware, as always, that his presence might seem bizarre to any newly arrived officer.

‘A votre service, Monsieur Williams.’

‘Much obliged to you in turn, Monsieur Laurent.’

Steel smiled and continued. ‘Observe too, Tom, how Monsieur Laurent retains the enviable manners of his nation.’ Laurent laughed, and raised his eyebrows.

‘And this is Captain Melville, late of my Lord Orkney’s Foot. And this gentleman over here with the permanent grin, is Lieutenant McInnery. Seamus to his friends, of whom he would have you think that there must be very many.’

He lowered his voice to a stage whisper: ‘Truth is, the poor fellow hasn’t one.’

McInnery laughed, and bowed to Williams. Steel moved between them.

‘Oh. And stay well clear of him, Thomas. He’ll lead you into bad ways. Within a week you’ll be penniless and ridden with the pox from some twopenny tart.’

McInnery shoved Steel hard in the shoulder. ‘Jack. What would you have the poor boy believe. Honestly, you go too far. I have a good mind to call you out.’

Steel looked hard at the Irishman and smiled. ‘But perhaps not today, though, Seamus. Eh?’

Steel’s attention was distracted by the arrival of the duty officer, Charles Frampton, Jennings’ crony. A bluff, Kentish man with no time for idle chatter but a seemingly unending capacity for wine which appeared to have no effect on him whatsoever.

‘Gentlemen. I think that we might address the matter in hand if we are to get it over with before midday, do you not?’

Steel whispered to Williams: ‘It seems, Tom, that our tea will have to wait. Although by the time this is finished I dare say you may be in want of something a little stronger.’

As the officers moved off to their respective companies, Steel looked about the makeshift parade ground. A square had been marked out by four flagpoles, to each of which was attached a square of red silk reserved for just such an occasion. On the farthest side of the square, directly in the centre of two of the poles a wooden frame had been erected using five halberds. Three had been tied together to form a triangle and a fourth then attached to the apex to act as a buttress thus making a tripod. The fifth had been tied directly across the centre of the triangle. At right angles to it, between the other flagpoles, stood three companies of the regiment. Steel’s, being that of the Grenadiers, was to the right and he now took his position at its rear. Nate helped him to mount his horse, a tall bay gelding. Steel looked at the bare structure of the whipping block and cursed. It never failed to astonish him that even now, with the army better fed and furnished than ever before, there were still some soldiers within its ranks foolish enough or hungry enough or just stupid enough to risk everything by stealing. And this was the army’s answer.

Slaughter, who was standing to his front spoke without turning his head.

‘It’s a bloody shame, Mister Steel, Sir. A real bloody shame. Dan Cussiter is no more a thief than I am.’

Steel lent over to pat his horse’s head. ‘Careful now, Jacob. That’s seditious talk. You know that the army no longer lives off the country. It is the Duke’s work. Every major or captain has the responsibility of telling every man in his company that if one of them steals so much as an egg they will be either hanged or flogged without mercy. And should that be the case then you know the good Major Jennings will always be on hand to ensure that justice is carried out to the letter of the law and within an inch of your life.’

Steel sat up in the saddle.

Slaughter spoke again, although he was still staring straight ahead. ‘Perhaps one day they’ll reform this army so that them as is good stays from harm and them that’s bad at heart get their just rewards.’

Steel said nothing, but entertained similar thoughts. Perhaps when some were turned to dung on the fields of Germany, then those left behind might yet benefit. But he very much doubted it. Marlborough could do many things, but he could not interfere with the very infrastructure of the army; the fact that everything worked only by example. And that meant punishing some poor bugger today, whether or not he really was a thief. Steel’s thoughts were lost in the growing thunder of a drum roll. Two men had been sentenced. As was the custom when the army was in the field, desperately attempting to preserve its manpower while unable to forgo military justice, only one was to be punished. So the two men had drawn lots to determine who would receive the flogging. The winner, a moon-faced oaf from number three company had been returned to the ranks and now stood smiling with grim satisfaction as he watched his partner in crime being led out into the square.

Cussiter stood between the Grenadiers of the escort with his head hanging down, staring at his feet, waiting for the inevitable. He had been stripped to the waist and his hands bound, ready to receive punishment, and the white of his thin flesh shone horribly stark and raw against the massed red coats of the parade and the grey of the unforgiving morning. A flogging was not the worst punishment that the army had to offer. There was death, of course, by shooting, hanging or breaking on the wheel – in which your bones were smashed with an iron bar before you were cut down and left in the dust of the parade ground to die slowly and in unimaginable agony, or until a merciful officer put his pistol to your head and blew your brains to the air. There were other ingenious punishments to suit particular crimes. Steel was familiar with the rules, some of which had been laid down by Marlborough himself for each offence.

‘All men found gathering peas or beans or under the pretence of rooting to be hanged as marauders without trial.’ There were also clear distinctions between what merited ‘severe punishment’, ‘most severe’ and ‘the utmost punishment’. Flogging, like the other common forms, was brutal and barbaric, yet Steel knew that there was really no other way. But it was hard to wipe from his mind the images of so many punishment parades and their various different methods.

There was the whirligig, in which the prisoner was placed in a wooden cage that was then spun on a spindle until he was so dizzy that at the least he suffered vomiting, involuntary defecation, urination and blinding headaches. At worst he would experience apoplectic seizures, internal bleeding and possibly death. Then there was the wooden horse on which the convicted man was compelled to sit astride while weights were gradually attached to each foot. It didn’t help if your victim happened to be among those administering the punishment, as so often seemed to be the case. It was said that a prolonged spell on the wooden horse could bring about rupture and destroy forever your chances of fathering a family; Steel had seen men very nearly gelded by the revolting contraption. But nothing, felt Steel, no product of the torturer’s ingenuity, could equal for sheer spectacle or barbarity, the horror of a simple flogging.

He wondered whether he was alone in feeling this way about what they were all about to watch. He knew that many officers shrugged it off with the casual nonchalance they might accord chastising a disobedient dog. Others though, he suspected, shared his qualms. Of course it was quite impossible to express such views. And Steel felt at times that perhaps it was a failing on his part. An inability to be quite everything that the men expected in an officer. Looking away from the tripod, Steel’s eye found his Colonel.

James Farquharson was sitting uncomfortably on his horse at the centre of one of the companies, surrounded by his immediate military family. Close to him sat Jennings and for an instant Steel contemplated how they might eventually resolve their quarrel. Whether one or both of them might die in the resolution or whether both might not be killed by the enemy first. Jennings was an unpopular enough officer. Perhaps he would die by a British bullet rather than by one of their enemies’. It happened. All too frequently in fact. Who could say in the heat of battle quite from where the deadly shot had come?

A little back from the punishment block Farquharson still felt too close for comfort and pulling at the reins of his handsome grey mare he coughed, nervously.

‘You know, Aubrey, I really do find all this so very tiresome.’

He belched and wiped his mouth with a white lace handkerchief he kept hidden in his sleeve.

‘I suppose that I must really remain until the end, eh. Until it is erm … finished?’

Jennings smiled. ‘I really don’t see how you can do otherwise, Sir James. It is after all your regiment. Not good for the men to see you go before the … erm … finish, Sir.’

‘Quite so, quite so. It was merely that I remembered a prior engagement you understand. Staff business as it were. You were not to know. It is of no matter, no matter at all. How many lashes did you say?’

‘A round hundred, Sir James. You yourself signed the warrant.’

‘A hundred. Yes indeed. Dreadful crime. Quite dreadful. What was it again?’

Jennings turned back to the parade without answering. He knew the real reason for his commanding officer’s desire to leave. And that it had nothing to do with ‘staff business’. He did not in truth respect Farquharson any more than he respected Steel. Neither, in his opinion, was the sort of officer who was wanted in a modern army. Oh, it would suffice in the sort of army on which Milord Marlborough had set his heart. But Jennings knew that modern warfare needed a quite different sort of man in command. Ruthless, inspiring, pitiless. Certainly Marlborough had shown his grasp of the new warfare at Schellenberg. That was real war. War without mercy. But Jennings could see that their great commander, like the old fools who commanded the majority of his regiments, had no stomach for the sort of warfare he envisaged. The new breed of soldier needed nerves of steel and undaunted courage. And such a soldier could, naturally, only be commanded by men like himself. The square was almost complete now. The remaining officers of the regiment rode into place with their respective companies. Jennings was joined by Charles Frampton who had completed his immediate duties.

‘Good afternoon, Charles.’

‘Aubrey. Sir James. Bloody business this. Can’t say that I really care for it.’

Farquharson smiled. Jennings spoke:

‘Nor I, Charles, in truth. But it is what the army requires. Distasteful business though it is.’

‘Oh, I did not mean that I disapproved of it. Not at all. Quite so. Absolutely necessary. No other way. I was merely hoping to have been able to have spent the morning at drill. Most important you know. Now. Where are we? Where is the dreadful fellow?’

Another rattle of side drums signalled the approach of the prisoner and escort. Dan Cussiter was a scrawny looking Yorkshire-born Private from number three company. According to tradition, he was led by two Grenadiers and Sergeant Stringer, whose weasel face was suffused with a grin. Stringer relished all punishment parades and liked to see the men suffer. He would walk round the frame soaking up every moment of the agony, and he looked up now at Jennings with the eager anticipation of a waiting terrier.

‘Colonel, Sah. Permission to proceed with the punishment, Sah.’

Farquharson nodded to Jennings who in turn nodded to Stringer.

‘Lay it on, Sarn’t.’

Two drummer boys in their shirtsleeves had taken up their positions on the left and right of the ghastly frame. Their comrades continued the drum roll as the prisoner was led to the wooden poles. Steel barely knew Cussiter. Certainly, he had seen him many times about the camp and on the march, but the man had never made a particular impression. He seemed somewhat anonymous, not at all the sort of fellow you might mark out as a potential criminal. Steel wondered exactly what he had done to deserve this punishment. Theft certainly, but of what and of what value? True, in the measure of things a hundred lashes was relatively light. Some men were sentenced to 1,000 lashes and more to be administered over a number of days or weeks. At least in Cussiter’s case it seemed likely that it would be done in one session.

The drums stopped as the man was tied with one hand on each side of the central halberd and his feet spread out at the wide base of the triangle. A corporal pressed a piece of folded leather into his mouth, a precaution lest he bite off his own tongue with the pain, but also a gag to prevent him from screaming and thus further disgracing himself and the regiment. Stringer stood to the left of the frame and nodded to one of the young drummer boys.

‘Drummers, do your duty.’

Steel watched as the boy raised the cat o’ nine tails above his head and rotated it twice in the air as he had been taught to do by the regimental farrier. It seemed to hover in the air before the boy brought it down with a slap across the man’s back. Steel watched as the white flesh began to seep red and winced as Cussiter’s body arched away from the blow. Now it was evident why the fifth halberd was tied across the triangle. There was to be no chance that the prisoner might be able to sink his torso forward and avoid the lash.

Stringer’s cruelly jubilant voice rang out across the silent parade ground: ‘One.’

The boy’s hand came up again and again the whip journeyed round his head before falling on the white back.

‘Two.’

Now the drummer boy drew the tails of the cat through the fingers of his left hand, as he had been taught to do between each stroke, to rid them of excess blood and any pieces of skin or flesh which might have attached themselves. Again the whip descended.

‘Three. Keep ’em high, lad.’ The last thing they wanted was for the strokes to fall on the man’s vital organs thus resulting in his death or being invalided out of the regiment.

‘Four.’ The cat whistled down again, the thick knots at the top of each thong cutting into the soft flesh of Cussiter’s back.

It seemed interminable. After the first twenty-five strokes the drummers changed and with the new boy came fresh agonies for the prisoner as the strokes began to fall from a different side and with a different pace.

‘Twenty-eight,’ boomed Stringer, his face split wide in a grin.

‘Twenty-nine.’

By the time they had reached fifty, the halfway mark, Cussiter’s body was sagging down, but his head still seemed to be holding itself aloft. The drummers paused as Stringer stepped forward to investigate what seemed to be a piece of exposed bone. He addressed the Adjutant. ‘Think I can see a rib sir.’

Steel looked. It was true. There was a glint of something pearly white against Cussiter’s bloodied flesh.

Jennings spoke: ‘No matter, Sarn’t. Carry on.’

There was an audible groan from the battalion. The battalion Sergeant-Major responded: ‘Silence in the ranks there. Corporal, take names.’

Two of the officers opposite Steel also began to whisper to each other. This was certainly most irregular. The idea was not to lay the man open to the bone so quickly. The punishment should really be suspended. Jennings nodded to Stringer and the drummers began again.

‘Fifty-one.’

Having had the blissful remission of a few seconds without the lash, Cussiter’s back arched out in a new extreme of contortion as the next stroke descended with renewed fury. Blood splashed up with every cut now. The drummers were soon covered and it flowed in slow rivulets down the victim’s back to form puddles around him in the dust. Even Steel looked away and wished the thing might end. In whatever way.

Looking across the parade ground to where Williams sat, he noticed that the young Ensign’s complexion was now quite white. Farquharson face too had turned ashen and it was evident that the Colonel was attempting to divert his eyes away from the spectacle.

Jennings, on the other hand, was staring with ghoulish fascination at the wreck of Cussiter’s back. After what seemed an eternity the words came at last.

‘One hundred.’

Stringer turned away from the bloody tripod and addressed the Colonel: ‘Punishment completed, Sah.’

Farquharson, mute with emotional exhaustion, said nothing, but merely nodded. Jennings gave the command: ‘Take him down.’

At the words the battalion seemed to relax as a man with a great sigh of relief that it was finally over. Hands fumbled at the ropes binding Cussiter to the halberds and he toppled sideways into the arms of a corporal, then steadied himself on his feet and attempted to walk away. It was a brave show, but in reality he needed two men to help him back to the company lines. Steel heard the clock tower chime. Half past ten. Damn waste of time, half-flaying a man alive. He would now most certainly be late for his appointment. But how could he have excused himself from attending without giving anything away? Not waiting for the other officers, Steel quietly told Slaughter to take over and turned his horse back towards the lines.

It was a good twenty minutes past the appointed hour before he found himself within Marlborough’s campaign tent. It was quite a fancy affair he thought, as befitted the Commander-in-Chief. Its walls were lined in red striped ticking and on the ground were laid a number of oriental carpets. Several pieces of furniture stood about the walls. A handsome console table with ormolu supports and a camp-bed, draped with red silk, stood in one of the darker corners, while in the centre of the room lay a large, polished oak table covered in maps and papers and several chairs.

The Duke stood with his back to Steel, who had been announced by an aide-de-camp, who stood hovering beside the tent flap. He was hunched over one of the maps, his fists pressed down on the tabletop. In another corner of the tent, apparently absorbed in leafing through the pages of a leather-bound book, stood Colonel Hawkins. As Steel entered he looked up and smiled before looking back at the pages. Marlborough spoke, without turning round.

‘You are late, Mister Steel. Tardiness is not something of which you make a habit, I hope.’

‘Not at all, Your Grace. My sincere apologies. The regiment was paraded for punishment. A flogging.’

‘Never a very pleasant business, Mister Steel. But absolutely necessary. We must have discipline at all costs, eh? Be fair to the men, Steel, but be firm with it. That’s the way to make an army. But now, here you are.’

The Duke turned and Steel recognized that face. Although it looked somewhat care-worn now, the brow furrowed as if by pain, yet still quite as handsome in close-up as he remembered. He had met the General only once before, at a court assembly, and doubted whether the great man would remember him. Marlborough, as usual, wore the dark red coat of a British General, decorated with a profusion of gold lace and under his coat the blue sash of the Order of the Garter. Most noticeably, rather than the high cavalry top-boots, favoured by most general officers, he wore a pair of long grey buttoning gaiters. He stared at Steel for a good two minutes as if getting the measure of this man to whom he had entrusted his future. Finally, he seemed satisfied.

‘Yes. Discipline is paramount. We cannot allow the army to run amok can we. It’s all they know, Steel. Good lads at heart. But how else to keep ’em in check, eh?’

‘Indeed, Your Grace.’

‘Now, Steel, to the matter in hand. Colonel Hawkins here tells me that you have been made aware of the importance of this mission. I merely wanted to commend you on your way and to hammer home beyond doubt the absolute necessity that you should succeed. This is no less than a matter of life and death, Steel. My death and now also your own.’

He smiled.

‘If you fail in this mission, if the document you seek should find its way into the hands of my enemies, they will as surely break me up like hounds falling upon a hare. And be assured, Mister Steel, that if you do fail then they will most certainly do the same to you.’

He paused. ‘I’m told, by my sources in London and by Colonel Hawkins, that you are a man to be trusted.’

He fixed Steel with strikingly cold grey-green eyes.

Steel swallowed: ‘I very much believe that to be true, Your Grace.’

‘It had better be, my boy.’

Steel felt a sudden impetuous curiosity which momentarily overcame his nervousness. ‘May I ask by whom in London I was named to you, Sir?’

Marlborough laughed. ‘No indeed, you may not, Sir. But I guess that you must already know. Shall we just call her ‘Milady’.

‘So then, Steel. D’you think you can do it? Can you save my skin and this blessed war?’

‘I shall do my utmost, Sir.’

‘Yes. I do believe you will. Bring me the papers, Steel, and I shall ensure that you are given fair reward. D’you take my meaning?’

‘Indeed, Your Grace. You are most generous. But in truth to serve you is honour and reward enough, Sir.’

Marlborough turned to Hawkins. ‘You were right, James. He does have a silver tongue. I can see what Milady must see in him. And I hear that you can fight too, Steel.’

‘I like to think I can acquit myself with a sword, Sir.’

‘I’m told you have a particular penchant for duelling, eh?’

‘Not really, Sir.’

‘Real or not, I won’t have it in the army if I can help it. Kills off my best officers before they have sight of the French. Waste of good men, Steel. Take my advice. Give it up.’ He turned back to the map.

‘What think you of the campaign thus far?’

‘Donauwörth was a great victory, Sir.’

Marlborough looked up and raised his eyebrows. ‘Indeed it was, Steel. But tell me. Was it enough? You know that my enemies decry the casualties. What though does the army feel?’

‘It is war, Sir. Men are killed in any battle. The fact is that we took the position and drove off the enemy. It was a glorious day, Sir.’

‘It is war, Steel. But this is a new war. Tomorrow we advance on the town of Rain. We shall besiege it and we shall take it, cannon or not. But you, Mister Steel, you will not be coming with us. You have your own orders and two days to prepare for your journey. Be swift and be sure, Steel. For if you are not, then we are all ruined.’

Aubrey Jennings sat in his tent writing up the company reports. It was the most tedious part of his job and normally he would have paid a junior officer to do the task. This evening though there was a general amnesty for all lieutenants and they had leave to visit the local village. So here he sat doing the job of a quartermaster, numbering off rations and issues of clothing, equipment, ammunition, and rum. Besides, he thought, it did allow him the opportunity for a little creative accounting. Who, after all, would know that the actual number of pairs of shoes delivered was 300 and not the 600 for which he had indented? The additional money would go straight into his pocket. Not bad for an evening’s work, tiresome as it was. Jennings sat back in his chair, closed his eyes and sighed.

‘God, Charles. I can’t abide paperwork. We should have clerks to do such things. Never would have happened in the old army. You know I can’t help thinking that we may have our priorities wrong. What need have the men for new shoes when there are hundreds of perfectly serviceable pairs being discarded? The men never needed regular supplies of new shoes before. Why now? What does Marlborough suppose it will buy him? Popularity? Of course he’s right. But he doesn’t have to sit here and write up the damned papers for the bloody things. I tell you, it’s typical of the way this army is going. I don’t like it, Charles. It’s not what soldiering’s about. Reforms yes, of course we need reforms. But not like this. Not reforms for new shoes. We need reforms for new men. New officers and a new code of fighting. I’m not liked you know, in Whitehall. I’ve been passed over. I should have command of a battalion.’

Charles Frampton spoke from a corner of the tent, without looking up from his book. ‘You could always raise your own regiment, Aubrey.’

‘D’you suppose I’m made of money, Charles. Don’t be ridiculous. Waste my own money on clothing and feeding 600 men. No. I intend to rise by merit and persuasion. It is my right.’

There was a cough from outside the tent. Jennings looked up and then back down again at the ledger and took up his pen. ‘Come.’

Stringer entered, leering.

‘Yes. What is it Sarn’t?’

‘Have to report, Sir. Men are a bit low, Sir.’

Jennings looked up at the grinning Sergeant and put down his pen.

‘Perhaps I had better go and raise their spirits. D’you think?’

‘No, I wouldn’t do that. No, Sir. Not if I was you, Sir. See, it’s the effect of the flogging, Sir. Never very happy after a flogging the men aren’t. There’s talk as you should have had ’im cut down after fifty, Sir.’

‘Oh there is, is there? Well Sarn’t, see if tomorrow you can’t listen a little closer as to where that talk is coming from and then we’ll see if whatever big-mouthed miscreant is the author of that treason doesn’t get a hundred lashes or more of his own for his trouble.’

Stringer grinned his toothless smile.

‘Very good, Sir. I’ll get about it now, Sir.’

Turning, he made to leave the tent, but before he could do so an officer entered, his red coat marked out by the distinctive green facings and grey waistcoat of Wood’s Regiment of Horse. Jennings knew him as a casual acquaintance. Thomas Stapleton, a Major of no little repute, testimony to which was born out by the white scar which ran the length of his right cheek. Jennings knew him too from London.

He suspected that Stapleton, with his obvious allegiances, must be as disenchanted with the motives and ambitions of their great commander as he was himself. Wondering what business Stapleton might now have with him, he rose from the table to greet him.

‘Major Stapleton. How very pleasant to see you again. To what do we owe your presence? A drop of claret perhaps. Charles.’

Frampton poured a glass and brought it across to them.

‘Thank you, Major Jennings. That would be most agreeable.’

Stapleton had been blessed from birth with a speech impediment, pronouncing all his ‘r’s as if they were ‘w’s. It had the effect of making his already high-pitched voice still more comical. But there was nothing amusing in the expression he wore as he accepted the proferred goblet of wine from Frampton. He took a sip and got to the matter in hand.

‘May I speak plainly?’

‘Major Stapleton. You may rest assured that you are among friends here. You know Captain Frampton?’

Major Stapleton nodded and then frowned: ‘Indeed. Nevertheless, Major Jennings.’

He raised his eyes towards Frampton. ‘If you would be so kind.’

Jennings turned to Frampton. ‘Charles. I’m afraid that I must ask you to leave us, briefly.’

Frampton walked slowly across to the entrance and Jennings, realizing that Stringer was still standing by the entrance to the tent, motioned for the Sergeant, too, to leave. Once both men had gone, Stapleton began:

‘Major Jennings. You will have heard, no doubt, that a wagon train was lately ambushed near Ingolstadt by a party of Bavarian cavalry.’

‘It is common knowledge, Major. Yes. But it was I believe of little consequence. It contained personal possessions mostly. No ammunition. No supplies.’

‘Quite true. Personal possessions certainly. A quantity of silverware and plate, fresh uniforms for the general officers. In fact the majority of it was the personal property of the Commander-in-Chief. What you were perhaps unaware of however, was that within those wagons was a chest of highly personal documents and correspondence belonging to His Grace the Duke of Marlborough.’

Jennings grinned. ‘How personal, exactly?’

‘The chest contained certain papers. Letters from his wife and so on.’

‘How very droll. Go on.’

‘The point is, Major, that finding no supplies of any military value, the Bavarian Colonel who captured the train sold on its contents to one of his countrymen, a merchant.

‘You will not be surprised I hazard if I tell you that said merchant, an inquisitive, inventive sort of chap, having glimpsed in one of the letters what seemed to him familiar armorial bearings, spent many hours perusing the papers.’

He took a long draught of wine.

‘Within a letter from the Duke to his wife, the man found concealed a very different piece of correspondence. A letter to Marlborough from the court of the exiled King James at St Germain. A letter thanking our General in the most friendly terms, for his concerns as to the Stuart pretender’s state of health and also for his enduring loyalty.’

Jennings was staring now. Smiling.

‘You begin to understand what this might imply?’

‘Perfectly. Do continue.’

‘Naturally, our Bavarian merchant, being a man with an eye for self-advancement, thought to return the letter to its owner – at a price – and therefore some days ago sent an emissary into our camp. In short he has arranged to sell it back to Marlborough for 500 crowns. And this, Major, is where I come in. Or rather, where you come in. I am informed that you and I are of the same political persuasion.’

‘I am a Tory, if that is what you mean. And a true patriot.’

‘Indeed. And being of that persuasion I venture that you would be as keen as I to see my Lord Marlborough replaced as commander-in-chief of this army?’

‘You hardly need ask, Major. The Duke’s ambitions will be the ruination of the army. He does all from self-interest, rather than the good of his country. If given his head he will sacrifice as many men as it takes to advance himself to the highest office. He must go.’

‘You will be aware too that the Margrave is discontented with the Duke’s conduct of the campaign. I have today learnt from one of Baden’s men on Marlborough’s staff that the Duke and Colonel Hawkins have contrived to send an expedition to procure the letter. It will leave within the week under the pretext of foraging for flour. It is to be led by an officer of your own regiment. A Lieutenant Steel.’

Jennings continued to smile.

‘You will appreciate, Major Jennings, that we have here an unmissable opportunity to bring down Marlborough and rescue this war for the Tories. Bavaria is no place for the army. Nor Flanders. It is, as my Lord Nottingham would have it, the only theatre in which to wage a war against the French is in Spain itself. It is vital that we put an end to the campaign before we are committed any deeper to this foolhardy expedition into Bavaria. Here is the answer. You will lead a counter-expedition to beat Steel to the merchant. I have arranged for Baden himself to ask Sir James for your temporary transfer to his forces as liaison. With luck Steel will know nothing of it; you will leave a full day after him. But you will not be hindered by wagons as he is. Take a parallel route and you are certain to reach the rendezvous ahead of him. You will meet the merchant, a Herr Kretzmer. Pass yourself off as Steel and procure the letter in exchange for the money.’ He smiled, as if struck by a sudden thought and spoke very quietly.

‘Of course in an ideal situation you might see to it that Herr Kretzmer no longer had any need for the money and return it to me. Or rather to the funds. Now that would be splendid. But no matter. It is spoken for. Simply procure the papers and on your return we shall send the traitorous document to London. The Queen will have no alternative but to dismiss Marlborough and banish his meddlesome wife from court. You and I shall be greeted as heroes, and our standing both in the army and the greater world will be without limit. Will you do it?’

Jennings raised his glass. ‘How can I possibly refuse?’

Reaching inside his coat, Stapleton drew out a bulging leather purse and placed it heavily on the table alongside the company ledger book.

‘This purse contains precisely 500 crowns. Herr Kretzmer will be expecting not a penny less.’

Jennings looked at the purse. ‘Rest assured, Major Stapleton, you may trust in me to get your papers. I will gratefully accept your reward on my return. But, believe me, I go to my task wholly in the conviction of the justice of our cause.’

As Stapleton left the tent, Frampton re-entered.

‘Well, Charles. It seems that my prayers, had I but said them, have been answered. And all at one stroke. Not only do I elevate myself to greater position, but I rid the army of the curse of Marlborough and in the same action destroy Steel. It is a conceit so perfect that I might have thought of it myself.’

Frampton said nothing. Merely nodded in assent and poured himself another goblet of claret. Jennings ran his hands down the side of the leather purse, feeling the outline of the coins within. At length he called out: ‘Stringer.’

The Sergeant appeared at the entrance of the tent.

‘Sarn’t. Better start saying your goodbyes. In three days’ time we are to leave the main body of the army and journey south.’

‘South, Sir?’

‘South, Stringer.’

Jennings smiled. ‘We’re going to save the army.’