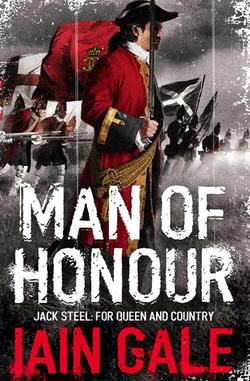

Читать книгу Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms - Iain Gale, Iain Gale - Страница 15

ОглавлениеSIX

Steel eased himself forward in the saddle and shifted position. Damn this leather. Surely, he should have learnt by now that anything bought as a bargain on campaign would quickly prove to be an utter waste of what little money he had. He moved again, carefully, lest the men should notice. There was a particular piece of the hard hide, just below the cantle, that kept on digging into his thigh and chafing the skin. He swore quietly and turned to the rider on his right. They sat at the head of the great column that wound for more than half a mile behind them through the sun-dappled Bavarian countryside.

‘You know, Tom, I sometimes think that we’d all be better off marching with the men than stuck up here on horses. What d’you say?’

‘My uncle says that the first duty of an officer is to maintain respect, Sir. Without respect, he says, there is no such thing as an officer.’

‘And a very wise man your uncle is, too. But what do you think?’

‘I think that I agree, Sir. I think that we should ride.’

‘Then I dare say that you and your uncle may be right. Although as you’ll learn, Tom, there is a good deal more to being an officer than merely keeping the men in order. They’ve got to trust you. How can they trust you if all they ever see of you is your horse’s backside? Eh? They may call Marlborough ‘Corporal John’. May even thank him nightly in their prayers – if they say them – for all he does to comfort them. But we must never forget, Tom, that they’re all scum at heart. They are a parcel of rogues and mercenaries. Lewd and dissipate creatures all. Where but the army would they find clothing, pay, and food? We give them all they could want. And in return they give us their lives. Marlborough knows it. You know it.’

The young Ensign smiled. Over the past week he had grown to like Steel and to value his companionship and advice freely given.

They had been on the road seven days now, the last two of which had been passed in loading the flour which would take Marlborough’s army to battle. The wagons were increasingly heavy and their pace slower by the day. Steel wished to God that they could get back to rejoin the army. His tasks, both evident and secret, had now been accomplished and the sooner he could convey the papers safely back to Colonel Hawkins, the better. At present the little bundle weighed like a lead ingot against his chest.

He turned back to Williams:

‘Quite a man, your uncle, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Uncle Septimus? Oh, I mean, Uncle James, Sir. Yes, he is rather.’

Steel laughed.

‘What did you call him?’

‘Er. Septimus, Sir.’

Again Steel laughed. Louder now. ‘Well, I’ll be buggered. Septimus.’

Williams blushed, concerned that he had betrayed Hawkins.

‘I shall remember that. Don’t worry, Tom. I shan’t tell anyone else. It’ll be our joke. Septimus indeed.’

They rode on in silence, Steel smirking at his amusing discovery, their harnesses jangling with a quite different note to the metallic rattle of the bayonets that marked the company’s every step. Behind them came half a platoon of the Grenadiers, led by Slaughter, and then the first of the forty flour wagons, on which travelled the regimental cook. Each of the wagons was flanked now by just two men apiece. One wagon had been commandeered for the wounded and after that rolled the agent’s carriage. For with their dragoons now ravaging the countryside and in light of the attack upon Jennings’ company by brigands, Herr Kretzmer had asked if he might travel with the column as far as the allied lines.

Behind his coach rode Jennings. He had toyed with the idea of travelling in the carriage with Kretzmer and tethering his horse to the rear rail. How much more convenient and comfortable. But the Bavarian was piss-poor company and hardly a conversationalist, and Jennings had elected to ride.

Behind him came Stringer, at the head of the remaining marching infantry of Jennings’ company, which made up the rearguard.

Following the encounters with the peasants and the French, they had changed formation in case of ambush and were returning to the camp by a different route from that on which either of the redcoat columns had entered Swabia. It took them a few miles further south, around the town of Aicha, and then curled up to the north-west and back again across the Lech. But it would be less obvious to anyone who might have been tracking their progress. It had been Steel’s idea and Jennings for once had accepted his advice. He knew the man prided himself on his fieldwork. That Steel had a nose for danger and that he made up what he lacked in more cosmopolitan attributes with a knowledge of country ways. For all his own farming background, rural matters were as foreign a country to Jennings as that in which they now found themselves. To him, Steel was a rustic, defined by his supreme lack of appropriate behaviour. Why, it was evident even in the way he fought. That business in the village for instance, he thought with disdain. What sort of fighting did Steel call that? Throwing bombs and picking individual targets. That wasn’t real soldiering. Nor was it particularly effective. Oh, Steel might have frightened off a few of the enemy. Might have left a few dead in the street, but that wasn’t soldiering. Jennings, on the other hand, had lined his men across the street and given fire by countermarching ranks, in the proper, prescribed manner. The French had returned his fire in the proper manner, and then both sides had retired, with honour.

Of course he had lost men. More men than Steel’s precious Grenadiers. Eleven dead and badly wounded from his remaining two score and ten, to be precise. But what of it? There would be no taking cover for his men, by God. Jennings’ men would stand and fight as all true British soldiers should. Not hide and dart about like Steel and his band of bomb-throwing misfits. In a real battle, Jennings knew, Steel would be useless. Here though, the country boy was so evidently in his element that Jennings was only too happy to use him. He indulged himself a pinch of snuff and laughed inwardly, secure in the knowledge that it would after all, be the last command that Steel would ever have.

Steel thought it curious that, since the confrontation at the village, they had observed nothing more of the enemy. His mind was troubled by the massacre; haunted by the vision of the dead children and the priest with the half-severed head. He was concerned too by the fact that in the ensuing skirmish so many of those responsible had escaped, including, he presumed, their commander. But there were deeper concerns too. What had those Grenadiers been doing there? They were a curious regiment. Not one that he had seen or known of before Schellenberg. Why, he wondered, had they been at the village and why had their commanding officer been so keen to engage their column?

And of course there was Jennings. His presence weighed heavily on Steel’s mind, as persistent and increasingly troublesome as the nagging pain of this damned saddle. The road wound on lazily through the rolling Swabian landscape and they settled into an easy rhythm. Grey-brown alpine cows gazed at the unlikely column from the fields and minute by laborious minute the sun grew more intense. At the small town of Klingen, where the road divided, rather than ride north on the road to Aicha, they branched south across a shallow river and soon began to climb again, more sharply now. Steel pointed.

‘Tom. D’you see that?’

They looked south, directly along their proposed line of march. Both men had seen the pall of black smoke that rose high above the treetops and climbed until it disappeared in low cloud. Steel caught the faint scent of fresh charcoal on the air.

‘Our men or theirs, Sir?’

‘Hard to say. But I wouldn’t have thought that Marlborough would send his raiding parties quite this far south.’

As they reached the crest of the next hill, Steel, who had now ridden slightly in advance of the head of the column, looked down into the valley and saw what appeared to be a considerable body of people on the road below, coming directly towards him. Unsure what to make of it, he motioned for Williams to join him. ‘You’ve got good eyes, Tom. What d’you reckon to them?’

The young Ensign peered down.

‘They look like civilians, Sir. A fair number of them too. Men of all ages, with women and children, and not a few animals. And carts, Sir. Loaded up with God knows what. What can it mean?’

‘I’ll tell you what that means, Mister Williams. That means that either those French bastards who did for Sattelberg are up there and this lot are on the run from them in fear of their skins, or it means that our own dragoons are out doing their job. And while I don’t like either explanation, I pray to God that it’s the latter. In truth, Tom, what you see there is part of all that’s left of that town up ahead. See the smoke? That’ll be their homes. Poor beggars. Where d’you suppose they’ll go to now. And what do you think they’ll think of us?’

They would soon find out. There was no avoiding the refugees, over a hundred of them. Doubtless a fraction of the total population, Steel thought, unless of course the others had already been put to the sword.

The miserable crowd grew closer. They were a unsettlingly broad social mix, forced into common suffering. The paupers together now with the merchants, each one of them carrying whatever they had been able to salvage. The richer ones pulled carts – for the horses must have been driven off into the fields and the cattle set free or butchered.

The two columns of carts and wagons only just had room to pass side by side on the narrow road. They passed one another in silence, save for the bleating of goats and the howling of babies cradled in their mothers’ arms. Steel looked down at the faces of the dispossessed Bavarians, streaked with tears and set grim with anger and despair. This, Steel thought, is the true face of our war. This picture of misery. The death of civilization.

Hardly had the townspeople passed them, when Williams broke the silence:

‘Look, Sir.’

A dust cloud told of the approach of a column of horsemen. Steel shaded his eyes against the sunlight and peered into the distance. There was possibly a full troop of them, he reckoned. Perhaps 150 men. For a moment he panicked. They wore red coats certainly, and they looked like dragoons. But were they English, Dutchmen, or French? After their encounter at Sattelberg he did not want to take any more chances. Raising his hand in the air, Steel reined Molly gently into the side of the road.

‘Halt.’

The column came to a clanking, grinding stop. Steel spoke again:

‘Grenadiers. Forward.’

From behind him, Slaughter and the forward half-platoon of Grenadiers marched in double-time until they were directly to his rear, formed in two ranks.

‘Make ready.’

Steel heard the men cock the locks of their guns and knew that the first rank would now have fallen to their knees, placing the butts of their weapons on the ground with the second at the ready close behind. That should do it. The cavalry, to his consternation, continued to advance towards them at a walk and finally came to an abrupt halt. At the moment of doing so, every trooper of their first three ranks drew his sword. Very neat, thought Steel. Whoever you are, you are good. The officer at the head of this red-coated cavalry, probably Steel adduced, from his lace, a Captain, rode forward with his Lieutenant and another trooper. All three looked grim faced and confident. Like the rest of the troop, the trio were covered in dust and soot and looked utterly exhausted. Steel noticed the broad orange sash around the Captain’s waist. So, they were Dutch. He could guess only too well what their mission might have been. Having reached the head of the column, both of the dragoon officers doffed their hats – short caps of light-brown fur – and their gesture was returned by Steel and Williams. The Captain, a brawny, moustachioed man with two days’ growth of beard on his swarthy skin, spoke first, in thickly accented English:

‘Captain Matthias van der Voert of the regiment of dragoons van Coerland, in the army of the United Provinces, Sir. May I enquire who you are and what business you have here?’

‘Lieutenant Jack Steel, Sir. Of Sir James Farquharson’s Regiment of Foot, in the Army of her Britannic Majesty, Queen Anne. I am here on Lord Marlborough’s business, Captain. We have a consignment of flour to be delivered to the army. Vital provisions, you understand.’

A thought entered his mind. ‘Perhaps you might be able supplement our escort?’

The Captain gazed down the line of wagons and saw the thinly spread force of ill-at-ease infantrymen.

‘I see why you might ask me that favour, Lieutenant. You’re a sitting target like that. But I’m afraid that I really cannot be of any assistance. I am under orders to continue through this country, with my men. We cannot be diverted from our task.’

‘May I enquire then as to the nature of your task, Captain?’

‘We have orders to burn any sizeable village or town in Bavaria that we find still inhabited and to turn out its people into the countryside. It is, I understand, to be done at the express command of your Lord Marlborough.’

Steel nodded his head. It was just as he had presumed. He pointed to the column of smoke.

‘That then, I imagine, Captain must be your work up ahead.’

‘We burnt that town last night, Lieutenant. Cleared it, so to speak. There’s nothing much left. Except the inn and an old church. No one there but an old innkeeper and his daughter. Very pretty. He’s ill and she wouldn’t move him. But they’re quite harmless. Good beer though, if my men have left you any. The girl says that her father’s something to do with the English. His relative lives in England, or some such thing. You may find out more. Please, persuade them to leave, if you can, Lieutenant. Our orders were simply to move the people on and burn their houses. We want no part in killing civilians. We left them alone there, just burned the houses. That’s what we were told to do.’

He looked genuinely concerned, but was obviously ultimately confident that he had carried out his orders to the letter.

‘They should leave. We’re not alone here, this country’s full of troops. Ours and theirs. Dutch, English, French. I wouldn’t stay there if I were them. An old man and a girl. What can they do? They’re dead meat, Lieutenant. Or worse.’

Steel was suddenly aware of a commotion from the rear of the column. He looked back along its length and saw that Jennings was trotting towards them. He was mouthing unintelligible words. The Dutch officer saw him too.

‘You have another officer?’

‘My superior. Our Adjutant. He prefers to travel towards the rear.’

The Dutchman shook his head. The English army never ceased to amuse him. Pleasant men to be sure, but such amateurs. They wage no war for seven years and then they march into the continent and blithely expect to take command. Someone had even told him recently that the English were now claiming to have invented the new system of firing by platoon which the Dutch infantry had been using for at least five years. He laughed and Steel smiled back. Jennings grew closer.

‘Mister Steel. What’s this? Introduce me.’

‘Major Jennings, Captain van der Voert of the dragoons, in the army of our friends in the United Provinces.’

Jennings flashed a disarming smile at the Dutchman.

‘My dear Captain. How very fortunate. Now we shall all travel together. The country is teeming with French troops and brigands of every description. My own command was attacked and we have lately fought an action against Frenchmen of the foulest sort …’

Van der Voert cut him short.

‘Major, I am indeed alarmed to hear of your encounters. But I am afraid that we cannot be travelling companions. We have specific orders, direct from the high command of the allied army. We proceed due west, Sir, and canot divert from our course.’

Steel interjected:

‘The Captain is under orders from the Duke of Marlborough himself, Sir. He is to lay waste Bavaria.’

Jennings stared at Steel, tight-lipped.

‘Then clearly we must not delay the good Captain from his duty. Good day to you, Sir.’

The Dutchman nodded.

‘Herr Major, Lieutenant. I am afraid that we must leave you. We have pressing work, you know. Your Lord keeps us busy.’

Steel grimaced. The Captain touched his hat and the others followed suit, then he turned with his men and rode back to the troop. Closing with them, he barked a gutteral order and with an impressive single movement, the dragoons returned their swords to their scabbards. Jennings, without a word, turned his horse and trotted back towards the rear of the column. Steel turned to Slaughter.

‘Stand the men down, Sarn’t.’

He watched the Dutch Captain lead his men off the road and into the fields so that they might ride past Steel’s column to ease its passage.

Steel looked at Slaughter:

‘Come on, Sarn’t. Let’s get to the bloody town before that inn, if it really exists, burns down.’

He sighed. ‘Christ, Jacob. I hope we find the army soon. I’m not sure how much more of this I can take.’

‘Sir?’

‘Major Jennings, Sarn’t. You know well enough what I mean.’

Slaughter smiled.

‘I know, Sir. And I know that we shouldn’t still be down here. We need to get back to the regiment. And if we don’t get back soon I reckon we’ll not just miss whatever battle there is. We’ll miss the whole bloody war.’

The town of Sielenbach, when they finally arrived there, was nothing less than Steel had expected. A smoking, charred ruin of what had once been the pride of its citizens. The redcoats advanced carefully up the long main street, pausing briefly at every road junction to look both ways, before crossing and peering into the ragged rooms of every ruined house to make sure that no one had indeed been left to die.

Steel knew that the men were tired and, worse than that, thirsty and low in morale. For them this whole expedition had been an inexplicable loss of face. They had covered themselves in blood and glory at the Schellenberg, only to be sent on this sutler’s errand. Steel, they would have followed anywhere, given the prospect of action, but now they were deep in the Bavarian heartland, guarding a wagon train of flour. They had rescued a senior officer and a company of musketeers. Had beaten off an attack by as ruthless a bunch of Frenchmen as you could ever encounter, with no help it seemed from that same officer, their own Adjutant, who had himself recently carried out a ruthless and undeserved punishment on one of their number. They had discovered a terrible massacre and buried the dead, including women and babes, and now they saw towns being put to the torch by their own side and the ordinary people, people like themselves, being forced out into the countryside. Steel knew his men would be wondering what was going on and right now the last thing he wanted to do was answer questions.

The Grenadiers looked up to Steel and believed in him as much as they did in anything. They knew his war record, that he had served with the Swedes and come through that hell unscathed. There was something very special about Mister Steel. He was lucky and, like all soldiers who were deeply superstitious, they thought that perhaps some of his luck would rub off on them. But at the end of the day, he would always be an officer. Steel, too, felt the distance between them at times like this. Oh, he knew that he could rely upon Slaughter to keep them in order. But unless they rested – really rested and found their humour once more – he knew that he might all too easily have a mutiny on his hands.

For better or worse, Steel had taken the flogged man, Cussiter, into his half-company on the day following his punishment. The man had come to him personally and begged to be admitted. Cussiter had real spirit and Steel knew instinctively that, given time he would make a fine Grenadier. But Cussiter was also full of hatred, in particular for Farquharson and Jennings. Given the mood of the men, who knew what slight provocation might be needed for Cussiter to give way to his feelings. Here in the heart of enemy territory, where anything might happen, no one would ever be the wiser. It was better surely to pre-empt any trouble. Get to the damned inn – if it still stood. Stand each man a flagon or two of the local brew and let them get some rest. Soldiers were easy to handle, if you knew their ways. It was all very fine for Colonel James (or was it Septimus) Hawkins to tell his nephew that the key to being a good officer was to maintain respect, but Steel knew better. Keep them in good humour and they’d fight for you. Provoke them too strongly and you were as much a dead man as the nearest Frenchie.

Steel reined in and jumped down from the saddle. Best now to show solidarity, get down among them and lead by example. Besides, his status as an officer on entering a town might as well go to blazes here. He was hardly expecting a reception committee from the Mayor. Slaughter looked at him, equally cheerless.

‘Begging your pardon, Sir, but was you proposing that we would spend the night here? In this godforsaken blackened hole?’

‘That I was, Jacob. That I was. This is Sielenbach and it seems to me to be as fine a place as any to kick off your boots.’

Then, almost as an afterthought, he added:

‘And remember. As far as we know the inn is still standing.’

Slaughter smiled. He said nothing, but began to walk with a new spring in his step.

‘The men seem dispirited, Jacob. I am not wrong?’

‘Never more true, Sir. There’s talk at all times of what they’re doing down here now and you know as well as I do, Mister Steel, that when a soldier lets those words cross his lips then them other thoughts cannot be far away.’

‘Cussiter?’

‘Oh, the lad’ll be fine, Sir. But it’s not just him as is grumbling.’

Slaughter paused, thoughtfully.

‘Best to stop here, as you say, Sir. And, just so you know, I’m keeping Dan Cussiter as far away as I can from our friend the Major. If you know what I mean. Bit of bad luck Jennings being the other officer to come with us. If you don’t mind my saying so.’

‘No, Jacob. I don’t mind you saying that at all.’

The crash of the men’s boots echoed on the dry, soot-stained cobbles and resounded through the empty streets. There was no other sound save the rattle of equipment and the trundle of the wagons as the column slid noisily into the town.

There were no dogs barking here, nor even any birdsong. The smell of burning timber hung heavy on the air.

It was the height of the morning now, a sunny summer day, when normally the street would have been alive with noise as tradesmen and townspeople went about their business. Today, though, Kirchenstrasse stood empty, the tall, proud houses that had lined its sides no more than burnt-out, smoking ruins, like the stumps of so many blackened, rotten teeth. In places the fires still smouldered, the embers a mocking reminder of the vanished comfort of their hearths.

Possessions lay littered across the cobbles where they had been abandoned or forgotten in the headlong rush of a populace eager to escape further horrors. Clothes, shoes and bags lay everywhere. Dolls and other toys, scorched and filthy, along with larger items. Chairs, wooden boxes, musical instruments. Naturally, anything of particular value left behind by the townspeople had been taken by the Dutch. There were a few exceptions. A gilt-framed painting of Christ in Majesty lay in a gutter and a grandfather clock stood incongruously in the centre of the road junction, where its owners, having tried desperately to save their most precious possession, had been forced to leave it. Books lay strewn around and everywhere sheaves of paper blew through the deserted streets.

At length they came in view of the church. As the first building that they had seen in the place that had not been reduced to cinders, it stunned them with its simple majesty. Rounding the corner and entering the square, where the church façade rose high against the brilliant blue of the sky, Steel saw that close to the basilica stood another building. The inn was indeed still there, just as the Dutch Captain had told him. With its gaily painted timberwork and bright blue gilly flowers growing in pots, it made a grotesque contrast with the devastation that lay all around it.

‘Sarn’t, I think we’ll stop here.’

Slaughter turned his head to the right:

‘Column, halt.’

‘Stand the men easy, Sarn’t Slaughter. Allow them fifteen minutes rest.’

Williams rode up, and with him Jennings. The Major seemed indignant:

‘Mister Steel. We have stopped. Tell me why?’

‘Why, Sir. Because this is our bivouac for the night.’

‘The night, Steel? But it is barely three o’clock of the afternoon. We surely have two more hours to march?’

‘The men, Major, need to stop. And this is as good a place as any. Indeed it is better, on many counts. And it has an inn.’

Jennings looked across the street where a painted sign with a running grey horse hung above the inn door.

‘Well, Steel. If you are convinced. Although I don’t suppose for a moment that they’ll have anything half decent.’

He turned to face the column.

‘Sarn’t Stringer. Where the devil is the oaf? Stringer. My bag.’

Jennings dismounted and strode across the square, followed by the ever-attendant Stringer, who had retrieved Jennings’ bag from the coach.

Steel called after him:

‘Oh, Major. There’s a landlord who’s old and sick and his daughter. Look out for them.’

He glanced at Slaughter.

‘I do hope that the Major finds the accommodation to his liking. Come on, Sarn’t, we’d best get this lot sorted for the night. We’ll leave the wagons here on the street. There’ll be no traffic through here in the next few hours. Oh, and Jacob.’

‘Sir.’

‘Find the men somewhere to sleep. There’s what looks a likely field over there, behind the church. Tell the Grenadiers they might have two flagons of ale apiece in the inn – if it’s to be had at all. Tell them I … tell them Lord Marlborough will stand the cost.’

‘Very good, Sir.’

‘Oh, and Jacob. Just so that you know, I shall be joining you out in the field. Jennings is in the inn – with his monkey – and nothing on earth could possibly persuade me to sleep under the same roof.’

Across the town square, Jennings pushed open the door of the inn and stepped inside, closely followed by his Sergeant. Rather than the dirty wine glasses and half-empty tankards of ale that he had expected to find still on the tables where the last customers might have left them, he was surprised to find the interior neat and tidy. The parlour was deserted, although a fire had been laid in the grate and a pile of plates stood on a dresser, ready to be set.

‘Hallo. Anyone? Hallo.’

A door opened at the back of the room and a girl walked in. Jennings knew real beauty when he saw it and it took only a moment for him to decide that by whatever means, before they left this place, he was going to seduce her.

She addressed him in the local dialect.

‘Good day. Oh. You are a soldier?’

‘Yes, English, Miss. Major Aubrey Jennings, Farquharson’s Regiment, at your service.’

He gave a low bow and removed his hat.

‘You are English? Then I speak to you in English.’

Her voice was wonderfully gentle. A sweet contrast to the harsh, masculine world he had just left outside. Her words though were bitter.

‘Tell me, Sir. Why should I trust the English? Your men come here and burn our town. Why? What have we done? We do not make war on you. Why? Why?’

Jennings, taken aback, said nothing. Then a thought entered his mind. Quite brilliant. ‘Dear Miss, excuse me, you have me at a disadvantage. I do not have your name, Miss …’

‘Weber. My name is Louisa Weber and this is my father’s inn.’

‘Dear Miss Weber. I have come to apologize. On behalf of his Grace the Duke of Marlborough, I offer you and your fellow townspeople his Grace’s most sincere apologies. We encountered some of your friends on our way here and have attempted to recompense them for any damage that has been done. Obviously the village is beyond redemption, but we must do what we can. I beseech you to believe me, on my honour as a soldier and a gentleman that this was no doing of the English. It was the action of our Dutch allies and will be punished with the death of those responsible.’

For a moment the girl stared at him. Then she took his meaning.

‘Oh. No, I. I did not want that. No killing. But the Dutch Captain explained to me. He said that they did this under orders from your Duke. That this was done to injure the Elector Max Emmanuel. To make him leave the French. That it is the English who ordered our town to be burnt.’

‘I assure you, Miss Weber. It was not. We have caught the men who did this, the Dutchmen, and they are even now travelling under armed escort on their way to Donauwörth to be tried under court martial. Be certain, they will be hanged.’

The girl looked at the floor.

‘I am sorry. I did not want them to die. The Captain seemed such a nice man. A real gentleman.’

‘My poor dear. How much you have to learn, particularly about soldiers. I shall teach you. We may some of us be officers but not all officers can be said to be gentlemen. You must understand that some men are not to be trusted. That man was no gentleman.’

He moved towards her, placing a hand upon her shoulder at the point where the cotton of her blouse met the tempting, downy softness of her pale skin. She flinched and then relaxed under the warmth of his touch. It had been so long since anyone had done that.

‘Dear Miss Weber. Louisa, if I may. You may trust an Englishman. You most certainly may trust me. Now come. Show me where I might rest tonight. I will pay of course and also for any food and wine you might be able to offer my men. We have had a long and arduous march in pursuit of your oppressors.’

Steel had inspected the Grenadiers’ bivouac for the night, a pasture to the rear of the church in the shade of a few apple trees. He left his own kit there with Slaughter and walked back towards the square. He had commended his gun into the particular care of the Sergeant, but the great sword still clanked at his side and in the ghostly stillness of the abandoned streets, he placed his hand on the scabbard. It seemed almost sacriligous to hear such a sound in a place so newly marked by war. At the edge of the square and down the length of the main road that led into the town from the north, the laden wagons stood in the late afternoon light with their drivers. Some of the wagoners had taken the dray teams out of their shafts and were watering them at a nearby trough. Steel had ordered Williams to position two sentries on permanent guard on the wagons and a picquet of three men at each of the roads leading into the town. That accounted for half of their entire force. The others he expected, as had been arranged, in the inn. They would have to be careful of course, he, Williams and Slaughter, that each man consumed only his allotted ration of ale. For while Steel’s plan could work well as a preventative measure, it could also all too easily, he realized, be turned against him.

He walked up to the inn and pushed open the door. It was a sizeable place which, before the late catastrophe, might have made a good profit from the pilgrim route which Hawkins had told him, ran through these hills. The interior reeked reassuringly of stale alcohol and pipe smoke. The room was quite empty and Steel made his way across to the open staircase which rose to the upper floors. He was contemplating whether he should ascend, when he heard a low groan from a half-open door at the rear of the room. Pushing it open, he peered in and saw the figure of an old man, tucked under a blanket in a large wooden chair. He appeared to be mumbling in his sleep.

‘He’s my father.’

The soft voice, in a gently accented English, startled him and, turning, Steel instinctively placed his hand on the hilt of his sword. The girl spoke again.

‘I’m sorry. I did not mean to alarm you.’

‘I’m not alarmed, Miss. You just took me by surprise.’

She was exquisitely beautiful, with piercing blue eyes and hair like spun straw. Steel was entranced.

‘You are English? Yes?’

‘Yes. That is, I’m from Scotland, Miss. But … yes. You might say I am.’

He was unsure as to whether she had understood him. It was really not important.

‘Captain, Lieutenant. Sir.’ She looked in vain for his badge of rank.

‘Lieutenant, Miss. Lieutenant Jack Steel of Farquharson’s Regiment, in the service of Queen Anne.’

He gave a short bow. Louisa smiled and again, he was frozen by her beauty.

‘My name is Louisa Weber, Lieutenant. You are welcome here. This is my father’s inn. Your other officer, Major … Jennings, told me that you have found the men who did this horrible thing to our town. That this is not your doing, but the work of the Dutch. I try to understand.’

Steel nodded and wondered exactly what Jennings had said to her. How he had explained that they had ‘found the men’.

Louisa knelt down on the floor beside her father and draped her arm lightly about his shoulders. She whispered something to him in German. Words of comfort on a day where none could help. She looked up at Steel, her beautiful eyes filled with despair.

‘My father is sick. We must throw ourselves on your mercy. My father has a cousin in England. Living in Harwich. Perhaps you know it. It is a fishing town. His cousin is a merchant. A very rich man, I think. Perhaps, if we could get passage back to England, I could give you money, Lieutenant. I have already told this to Major Jennings. He says it will be fine. I told him my father’s cousin will pay. It is now the only thing to do, I think. We are ruined here now.’

Steel felt truly sorry for her. She was right. The town had ceased to exist. The dragoons had left only the inn and the church standing but what use was an inn with no prospect of customers?

‘Of course, Miss Weber. Of course we will do everything that we can to help you. And your father. And please, we will not take your money. Whatever Major Jennings might have said. Please.’

How very typical of Jennings, he thought, to have accepted her offer of payment. He extended his hand to help her to her feet and as he did so, the door on to the square opened and Slaughter entered. Clearing his throat, he called through to Steel who he could see through the door to the back room.

‘Mister Steel, Sir. I was wondering if now would be the right time for the men to get that ration of ale. We’re fair parched.’

Steel appeared. ‘Quite the right time, Sarn’t. Send them in.’

He turned to Louisa, who had followed.

‘Miss Weber. I take it that you can provide us with some ale? We have the money to pay for it. And whatever food you have to hand would be most welcome. If you could find a little wine, I would be very grateful.’

Happy for this semblance of normality, Louisa busied herself with attending to her guests.

The Grenadiers gradually filled the inn. They removed their caps as they entered and, piling their arms by the door, sat in groups at the tables. Within minutes the place was alive with noise. Steel watched Louisa as she moved among the soldiers and saw the change in her. How animated she had become. How very much more alive. He kept a low profile, sitting on his own in a dark corner beside the inglenook fireplace, although happily acknowledging any of the men who passed. Louisa had found him a pitcher of good Moselle and, although he could have drained it within minutes, he was pacing himself, anxious to keep an eye on the men. Slaughter, although he had taken his place within a group of senior other ranks, was exercising similar prudence. But neither man need have worried. One table was engaged in a game of cards. Another singing a round-work, whose ancient folk lyrics they had replaced with something rather more ribald. Steel watched the men relax for the first time in days and guessed that his tactic might have paid off. Slaughter caught his eye from across the room and nodded discreetly. Now, being convinced he could relax himself, from his shadowy obscurity Steel indulged in glimpses of Louisa as she made her way through the fug, serving the tall steins of sweet, dark brown ale, Dunkel, which in this part of Bavaria was the staple beer. From nowhere, too, she had conjured up a stew – thin but hot and satisfying and there was good black bread to go with it and ham and slabs of cheese – without the customary weevils.

The men, conscious that an officer was present, and that he was paying the bill, made no attempt to molest Louisa. He saw her smile, her pretty face lit from within and wondered unexpectedly how convincingly Jennings had entranced her with his unctuous words and promises. Then, catching the thought, puzzled how he could be jealous of that man, and why. He had only known this girl less than an hour. Had hardly spoken to her. And yet there was something about her that felt somehow … comfortable.

He saw Williams enter the inn and look about the room. A table of Grenadiers looked up and grinned. As the new boy of the company, the Ensign was still an object of fun, even though he had won his spurs in the skirmish with the French. Steel called across to him.

‘Tom. Over here. Come and join me in a glass.’

Williams sat down and Steel filled two glasses.

‘Any sign of our friend the Major?’

‘None, Sir. I presumed that he might be in here.’

‘And Herr Kretzmer?’

‘No, Sir. Although he might be in his carriage.’

‘So, Tom. I promised that I would ask again after your first battle. How do you like soldiering now?’

‘I have not revised my opinion, Sir. Although, in truth, I must admit being unsettled by what we discovered at Sattelberg. Surely, Sir, that cannot be a true picture of war?’

‘No, Tom. War is not often like that. But the truth about war is that you can never be quite sure what will happen next. Sattelberg was bad. But take it from me, in your time as a soldier you will see worse. Far worse. And yet there are times, too, when you will know that there is nothing like it in all the world. It is the most exciting and the most tedious of lives. A challenge and a drudge. And if you stay with it I will guarantee that there will not be a day in which you will not encounter something that will either make your soul leap with joy or your spine shiver with dread apprehension.’

Three hours later Tom Williams was still lost in dreams of soldiering. Steel helped him to his feet. Tom had, Steel thought, perhaps indulged in just a little too much wine. Most of the Grenadiers had left the inn now, bound for the dubious comfort of their field bivouac. As the last few made their way towards the door, one with the words of a song on his lips and the rest with muttered thanks to their officer, Steel called to Slaughter.

‘Sarn’t. Will you be so kind as to help Mister Williams to his quarters. Place him close by me. Not so close though that should he awake in the night he might make the mistake of taking my kit for a latrine.’

Slaughter laughed.

‘I thought he looked a bit groggy, Sir. Unused to the wine, I suppose, and there’s hardly anything to him. I’ll see to him, Mister Steel. You take your time.’

Slaughter had watched his officer all evening and had seen how he gazed at Louisa. He had known Steel long enough to understand what that look meant. Well, perhaps there would be time for love, if that was what he wanted. He recalled one drunken, desperate night in Flanders, after a day on which they had seen too many good men die, when Steel had told Slaughter about a girl called Arabella. About regrets and missed opportunities and what he had hoped life might hold for him. The following day of course, nothing more had been said. But the Sergeant had not forgotten his officer’s confidences. Maybe this girl would follow them now. Perhaps she would be the one to offer Steel the life he craved. Cradling Tom Williams’ comatose form in his great arms, Slaughter stepped from the inn and Steel found himself alone. He walked across to the door of the Webers’ private quarters and gave a gentle cough. Louisa turned and saw him.

‘I suppose that I should move Herr Kretzmer.’

Steel nodded in the direction of the Bavarian, who, having purchased a bottle of fine French brandy from Louisa, had crept away from the soldiers to occupy the chair lately vacated by her ailing father and proceeded to drink the contents. Louisa did not mind. Herr Kretzmer came from a different world to the Grenadiers and he did not mix easily. She was happy to indulge her countryman. Together, she and Steel gazed on his sleeping form.

‘Leave him if you wish, Lieutenant. I will put a blanket over him and if he wakes up he will know which room to go to. Don’t worry. He’s as harmless as a puppy.’

Steel laughed.

‘Thank you, Miss Weber, for all your hospitality. May I settle our account in the morning? We rise early.’

‘As I do, Lieutenant. And please, call me Louisa. You are most welcome. It really felt as if the town were still … alive. I …’

She was suddenly lost for words. Instinctively Steel walked across to her. Gently placing an arm upon her shoulders, he looked into eyes which brimmed with tears.

‘Please. There is no need to worry. Tomorrow, you will come with us. Bring whatever is important to you but please, don’t worry. We will take care of you now. There is nothing more to fear. This is not an end, but a new beginning.’

She nodded, smiled, and for a moment Steel thought that he could detect in her eyes a spark of something more. Now though, he sensed, was not the moment. Steel withdrew his arm from her shoulder.

‘Now, you must get some sleep. Tomorrow we march north. And you start a new life.’

Jennings was looking for drink. Following Kretzmer’s departure, he had spent the best part of an hour in the church, deep in thought, if not in prayer. Then, feeling the pangs of hunger, he had sent Stringer into the inn to sniff him out what wine and food he could. He had chosen to eat his sparse supper alone, in the candle-lit gloom of the church, while his Sergeant sat outside on the steps. Now though, the man had reported that the Grenadiers, Mister Steel included, had retired for the night to their bivouac. Now at last, thought Jennings, he could enjoy the comforts for which he had paid. A real bed with clean sheets and perhaps before that a little more sustenance. And then, of course, there was the girl.

Leaving the church he walked quietly into the street. Stringer was waiting outside, leaning against a wall of the basilica. Seeing Jennings he straightened up. Now, in the moonlight, the town presented a truly eerie prospect. The night was chill and even Jennings felt a sense of unnatural unease. He walked over to the Sergeant.

‘I want no one admitted to the inn on any account. No one. D’you take my meaning, Sarn’t?’

‘Sir. Yes, Sir.’

Quickly now, Jennings moved to the inn and eased the latch of the door. It was unlocked. Inside, the room stood empty and dark. All the candles but one had been extinguished and the tables cleared. A light from the door at the rear betrayed the fact that the house had not quite gone to bed. Doubtless there he would find his brandy. And the possibility of other pleasures.

He walked softly across the wooden boards, holding his sword close to his side and pushed open the door.

‘Miss Weber. How charming.’

Louisa gave a start and turned abruptly.

‘Oh. Major Jennings. You gave me a fright. I am sorry. I was dreaming.’

‘Of course. So like a woman. I was wondering if you might have a glass of cognac? Or indeed any fortified wine? I have had a busy night. Writing reports and so on. It would settle my nerves. No time for those in command to indulge themselves with the men.’

Louisa flashed him a sympathetic smile.

‘Yes, Major. Of course. I think that we have some good French brandy. Allow me to get it for you.’

Moving further into the room, Jennings noticed Kretzmer asleep in the chair and instantly saw his opportunity. How very obliging, he thought, of the fat Bavarian.

Louisa had turned her back to him now and was stretching up to the high store cupboard where they kept the good stuff. After all the Major would pay. She sensed that he was suddenly closer and felt his breath on her neck as he spoke:

‘You will recall, my dear, our conversation earlier. Our bargain. Your safe conduct to the English army. We agreed on a sum, did we not?’

Louisa turned to face him and found it difficult to avoid contact. She held the bottle between them.

‘Your brandy, Major.’

Jennings backed off a short way.

‘You do recall though, Miss Weber … Louisa. The sum of which we spoke?’

She nodded. ‘Yes, Major. But since then, things have changed. Lieutenant Steel has promised to take me to your army. He says that it will not cost me anything. That he will protect me.’

It was the worst thing that she could have said, and it sealed her fate.

‘Mister Steel told you that, did he? Let me remind you, Miss Weber, that we struck a bargain and by my code of conduct, a bargain once made, cannot be undone. So, Miss. Unless you want us to leave you here to the tender mercies of the French, you’ll pay up.’

He paused and smiled at her.

‘Although, there is of course, another way. A way which would both save your hard-earned money and provide us both with a pleasurable diversion.’

Louisa blanched and looked at Jennings. Could he mean it? Was he really asking her to sell herself to him in exchange for their passage north?

‘Major. You cannot mean what I suppose you to, surely?’

Jennings nodded and smiled.

‘No. You cannot mean it.’

He was breathing harder now.

‘Oh, but I do, pretty Louisa. I do mean it. So very, very earnestly.’

He saw her look of utter revulsion.

‘What? No? Then, by God, I’ll have you for nothing.’

Louisa opened her mouth to scream, but before she was able to utter a sound, his hand, rough and stinking of wine and filth, had been clamped hard over her lips. She tried to bite him, but her teeth could not reach the flat of his palm. Jennings pushed his body hard up against her and growled into her face.

‘Now, my pretty girl. You and I are going to have some fun. And if you scream or try anything else silly, all I have to do is call to my Sergeant – you remember him, he’s outside now – and he’ll slit your father’s throat, from ear to ear. And I’ll blame it all on this one.’

He jerked his head in the direction of the sleeping Kretzmer. As he watched her eyes widen with terror at the realization that all was hopeless, Jennings instantly became yet more aroused and decided that it would be safe to remove his hand.

‘So tell me. Where’s your precious Mister Steel now? No? I’ll tell you. He’s fast asleep in the field with his men. He won’t hear you. He won’t help you now.’

Jennings stretched out his hand and inserted a finger in between the lace of the neckline of her white blouse and the soft flesh of her shoulder.

‘Now, Miss. If you please. Your shirt.’

Louisa shuddered and froze. Jennings moved his hand further in, beneath the material and lifted it off her body, pushing it down her arm, then did the same on the other side. Then, with one swift motion he pushed down with both hands and she was naked from the waist up, horribly exposed to his gaze. Not bad, he thought. For a peasant. Her hand reached for a knife which she had remembered lay on the table behind her. But his was faster. Their fingers collided and the blade clattered to the floor as Jennings caught her by the wrist and with his other hand slapped her hard across the face, making her whimper.

‘You stupid German cow. Remember what I said, Miss. One word. One more stupid thing like that and the old man dies. Now. Help me.’

He reached for her thighs. She struggled, instinct taking over from reason. But his grip was an iron vice.

‘My, you’re a game one.’

He was used to this, she thought, through the red mist of terror and outrage which clouded her reason – the natural reaction which had kicked in to make all that would now happen appear unreal. He knew what he was doing. Had done it before. How many times, she wondered? How many women?

Jennings fumbled beneath her skirts then, impatient, ripped them to one side. He probed clumsily with his fingers and finding what he wanted, quickly unbuttoned his breeches. Desperate, lest she should utter a sound and condemn her father, Louisa bit hard into her own hand. Jennings, smiling with pleasure and hatred as he pushed at her, grunted out staccato words:

‘Remember. Tell them I did this and I kill your father.’

After the horror and humiliation of what had just occurred, the act itself took less time and effort than she had imagined. She felt Jennings shudder and relax and she recoiled from the stink of his foul breath as he nuzzled his head into her neck in a ghastly parody of genuine lovemaking. She felt unspeakably defiled and desperate to rid herself of this man. To somehow achieve the impossible and cleanse her sullied body.

Then it was over. Jennings straightened up, buttoned his breeches and adjusted his dress. His eye was caught by the gleam of candlelight upon the small knife that lay on the floor. Picking it up he looked down on the cowering, half-naked girl. It had been in his mind to slit her throat, but as he stood there another idea struck him. Something more deliciously cruel. He pocketed the knife and pointed to Kretzmer.

‘Now. Quickly. Help me with his breeches.’

Louisa stared. Surely the man was not so perverted that he intended to force her to couple with Kretzmer? She watched, traumatized, as the Major pulled the knife from his pocket and winced as he used it to make a careful, but not too deep cut in his own hand. Finished, he placed its sticky handle in Kretzmer’s palm, before withdrawing it and letting it fall again.

Then, and with no little effort, Jennings picked up the fat merchant, who all the time had remained comatose, and lifting him under his arms from the back, dragged him across the floor towards where Louisa stood, white, half-naked and trembling.

‘Come on, whore. Get on with it. Undo his buttons.’

Hardly aware now of her actions, Louisa reached out and deftly unbuttoned the front of the merchant’s breeches. As she finished and they fell from his corpulent form, Jennings pushed the man towards her, so that the two of them tumbled to the floor, sprawling, the half-naked girl pinned down under the Bavarian’s dead-weight. The impact brought Kretzmer round to semi-consciousness and Jennings bent down and placed the man’s fat hands on Louisa’s breasts, smiling at her as he did so.

‘Thank you, my dear. I trust that you enjoyed that as much as I. Or did you not? And remember. One word of the truth and your father dies.’

He slapped Kretzmer on the face, hard, knocking him into consciousness. Bewildered, the merchant pressed down instinctively on his hands to raise himself off the floor and in doing so found that he was embracing Louisa. He was lost for words.

Jennings turned to the door and, making sure that the grotesque sexual vignette was still perfectly arranged on the floor, shouted into the night, at the top of his voice.

‘Guard. Guard. Quickly. To me. Assault. Alarm.’

And from the empty streets of the dead town there came at last the sound of soldiers, hurrying to the rescue.