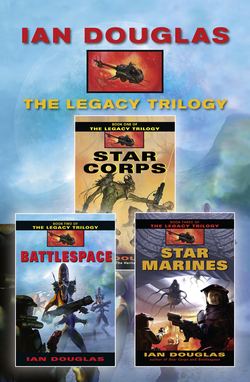

Читать книгу The Complete Legacy Trilogy: Star Corps, Battlespace, Star Marines - Ian Douglas, Matthew Taylor - Страница 10

2

Оглавление2 JUNE 2138

Listening Post 14, the Singer

Europa

1711 hours Zulu

And further still from Earth, some 780 million kilometers from the warmth of a shrunken, distance-dwindled sun, a solitary figure crouched on top of the half-surfaced ruin of a half-million-year-old artifact, high above the swarming camps of humans who studied it. The figure was not human, and in this modality didn’t share even a basic humanoid shape with his builders. Humans called this model “the spider,” because of the low-slung, flattened body, the eight spindly legs, and the cluster of eye lenses and manipulators set into his forward armored casing.

He was patient, as only an artificial intelligence could be patient. AI-symbiont CS-1289, Series G-4, Model 8, known to his human companion as Cassius, had waited here in the icy cold for just over 4.147 megaseconds now, some forty-eight days in human terms. By slowing his time sense by a factor of 3,600, however, his wait thus far had seemed more like nineteen hours, and even those hours, passing uneventfully, were accepted without emotion or anxiety, as much a part of Cassius’s environment as the ice and the near-perfect vacuum around him.

The surrounding landscape—icescape would be a more appropriate term—was a jumble of crushed and broken structures, towers, pylons, Gothic arches, and towering stacks of smoothed and round-cornered buildings, all encrusted with mottled gray-black and white ice. The swollen orb of Jupiter hung low in the sky, just above one of the radiation-blasted pressure ridges that crisscrossed the icy moon’s frozen surface. Europa circled Jupiter in just over three days, thirteen hours. With the time compression, eighty-five hours passed in what seemed to Cassius like a minute and forty-one seconds; shrunken sun and unwinking stars drifted across the sky from horizon to horizon in just fifty seconds. The swollen orb of Jupiter itself always remained in the same area of the sky, bobbing with Europa’s libration as the moon orbited in tide-locked step about its primary, but the banded disk waxed and waned through a complete cycle of phases, from full to crescent and dark, then back to full, all in a single time-compressed “day.” The other Jovian moons, from the silvery disk of Ganymede to a handful of stars, circled the giant planet, each at a different pace. Beneath that spectacular light show, across Europa’s frozen surface, shadows swung along the undulating ice, shrinking with the fast-rising sun, vanishing at high noon, then lengthening into the darkness of the short night, a cycle three days long compressed into a perceived handful of seconds.

From time to time Cassius was aware of humans moving through his circle of awareness, brief, blurred flickers of motion. He checked each, but at a subliminal, unconscious level. Had any lacked the requisite IFF codes or trespassed into unauthorized zones, his time sense would at once have defaulted to one-to-one, allowing him to challenge the interloper.

A human might have been lonely, but Cassius accepted the isolated duty as simply another mission within his design specs and parameters. He was aware of human activity in the area, of course. The tilted, roughly disk-shaped bulge of the Singer exposed above the frozen wastes of Europa’s world-ocean ice cap was ringed by a dozen small camps, pressure domes, habs, and radshield generators providing access to the mountain-sized mass of alien technology locked in the broken ice. Lights blazed around the perimeter, each casting pools of warm yellow radiance to hold the cold and darkness at bay, but Cassius was more aware of the radio chatter and telemetry, voices and streams of data whispering just above the eternal hiss and crackle of Jupiter’s radiation belts.

The human activity was all routine, electronic exchanges depersonalized to the point of tedium.

Seventy-one years before, the Singer had been discovered deep in Europa’s ocean, locked away beneath the eternal, planetwide ice cap. Europa’s seas were host to teeming, myriad life-forms—sulfur-based thermovores thriving around the Europan equivalent of deep-sea volcanic vents. The Singer, however, was from somewhere else, somewhere outside the Solar system, a product of an advanced technology that had mastered star travel at just about the same time that Homo erectus was evolving—or was being evolved, rather—into archaic Homo sapiens. Half a million years ago the Singer had been involved in a fight of some kind, a battle that resulted in the destruction of a colony of different aliens then thriving on the surface of Mars, at Cydonia. Damaged, it had crashed through the Europan ice cap and was stranded.

But not killed. The bizarre machine intelligence that called itself Life Seeker, which humans dubbed “the Singer” because of its eerie, ocean-locked wail, had waited out the millennia, eventually sinking into insanity—some believed out of sheer loneliness. When humans had approached it seventy-one years before, it roused itself from schizophrenic dreamings and attempted to break free. Piercing the ice, it transmitted a broadband radio pulse of incredible power to the stars and then, its scant energy reserves exhausted, died.

The Singer had been silent ever since.

Silent, that is, save for the noisy monkey-pack swarmings of human explorers, archeotechnologists, xenosophontologists, and exocyberneticists. As soon as the brief Sino-Confederation War of 2067 had ended, a steady stream of human ships made their way into the Deeps beyond the orbit of Mars, voyaging to the coterie of moons circling Jupiter. The Singer might be dead, but the kilometer-wide corpse was a solid mass of advanced alien technologies, an immense computer, essentially, that once had housed a self-aware intelligence far exceeding humankind’s. For seven decades human science had been plumbing the depths of the Singer, gleaning a host of technological tricks, arts, and secrets. There were endless promises of new and near-magical means of generating limitless power, of bending gravity to human will, of generating nucleomagnetic fields powerful enough to block a thermonuclear blast and sever the fabric of space itself, of new structural materials millennia beyond current manufacturing understanding, of computers and AIs of superhuman speed and capability, even—whisper the mere possibility softly—of the chance that one day humans might venture to the stars at speeds vastly exceeding that of light.

Such were the promises of the inert Singer … promises still far from being realized. In seventy-two years, Earth’s best scientists had barely begun to catalog the wonders still locked away inside that dead and ice-bound hulk. It might be centuries more before hints, guesses, speculations, and grueling work in the frozen hell of Europa’s 140-degree-Kelvin embrace generated useful technology.

Those promises, however, were so golden that accredited scientists were not the only mammals scavenging through the Singer’s dark, cold corridors. Five years ago a couple of research assistants with a Pakistani archeotechnological team had been caught by Marine security personnel with nearly forty kilos of Singer material—bits and pieces of structural support members and paneling, the equivalent of computer circuit boards, dozens of the fist-sized crystals believed to be used as memory storage media, and several oddly shaped artifacts of completely alien design and unknown purpose.

That hadn’t been the first time site robbers managed to infiltrate the legitimate science teams and smuggle out pieces of the alien ship. Bits of Singer technology had been appearing on Earth for at least the past ten years. Collectors reportedly had paid as much as fifteen million newdollars for fragments mounted and privately displayed as … art. The most startling case on record was the three-meter-wide slice of alien hull metal found hanging behind the altar of the Church of the Gray Redeemers in Los Angeles. When that had been smuggled back to Earth, and how, was anybody’s guess.

The U.S. Marines had been the guarantors of the Singer archeological site’s security ever since the end of the Sino-Confederation War. Once it was realized that covert looters were making off with fragments of the alien ship and selling them as curios, as art, and even as religious relics, the newly formed Confederation Department of Archeotechnology authorized the use of military AIs as sentries. Cassius had been assigned to Outwatch duty eight months ago, when the rest of his constellation—the twelve Marine officers and NCOs of cybergroup Delta Sierra 219—had been deployed to Cydonia. There was little need of team AIs on Mars, where the duty was routine and the local net provided reliable data and technoumetic access. On Europa his considerable skills and more-than-human senses could be put to good use patrolling the Singer artifact, protecting it and the Confederation science teams.

In eight months there’d been no incidents. Everything was strictly routine … which was, after all, the best way for things to be. Another sixteen months, and he would be able to rejoin his constellation back on Earth. Though it was difficult to say whether what he felt for his teammates was truly akin to human emotion, he did miss them… .

A radio signal caught his attention, and he instantly shifted back to standard temporal perception. The sun stopped its rapid drift across the sky, coming to a halt just above the golden-orange crescent of Jupiter. The shadows froze motionless in the patterns of mid-afternoon.

A Navy lander was descending from the west, balancing itself down gently with plasma thrusters against Europa’s 131-centimeters-per-second-squared gravitational tug. IFF tagged the dull black and silver sphere as a lander from the Outwatch frigate Kamael, currently in Europa orbit.

And a radio transmission from the Singer main base was already calling him in. “Cassius, this is Outwatch Europa. RTB, repeat, RTB.”

Return to base? He was not scheduled to leave Listening Post 14 for another 105 hours.

But more so than for a human, even for a human Marine, orders were decidedly orders. He extended his spider legs to full length and began picking his way down the icy slope of the Singer’s hull, making his way rapidly toward the main base.

The lander had been sent for him. He wondered why.

Giza Complex

Kingdom of Allah, Earth

1815 hours Zulu

“Here they come!” Captain Warhurst yelled. A thousand armed men, at least, sprinted into the open, screaming and firing wildly. Most were on foot, but a number of vehicles were mixed in with the surging mob—open-topped flatbed trucks with gun crews in the back, and light cargo hovercraft of various sizes and descriptions. “Commence firing!”

Warhurst leaned forward against the low wall of sandbags, moving his weapon to drag the targeting reticle into line with one of the charging Mahdi shock troops, a big man in mismatched pieces of Chinese and Persian armor, carrying a K-90 assault rifle. A touch of the firing stud, and the LR-2120 hummed, the vibration of the charge cycler flywheel barely perceptible through his armor.

There was no flash or visible pulse of light. Such wasteful displays of pyrotechnics belonged solely to the noumenal fantasies of VR thrillers. The laser pulse lasted for only one hundredth of a second, far too brief a period to register on the human eye even if there’d been dust or smoke in the atmosphere to make the light visible. The LR-2120 had a pulse output of fifty megawatts; one watt for one second equals one joule, so the energy striking the target equaled half a million joules—equivalent to the explosive power released by the detonation of fifty grams of CRX-80 blasting compound, or a tenth of a stick of old-fashioned dynamite.

The pulse explosively vaporized a fist-sized chunk of the man’s polylam breastplate as well as the cloth, flesh, and bone underneath, slamming him back a step before he crumpled to the sand. Warhurst shifted targets and fired again … and again …

The attack had been gathering all day. Kingdom of Allah troops and Mahdi fanatics had begun spilling across the Giza and Duqqi bridges out of Cairo early that morning, shortly after the Marines secured their slender perimeter about the Giza complex, but they stayed within the cluttered, narrow streets between Giza and the river, mingling with a fast-swelling crowd of civilians who chanted and waved banners. The Marines found it amusing. The signs and banners, for the most part, were in English, as were the chants. Clearly, the demonstration was for the benefit of the net news services and their floating camera eyes, which by now saturated the battlefield area as completely as the Marines’ own recon probes.

By mid-afternoon, however, the demonstrators had dwindled away, most of them crossing the Nile bridges back into Cairo proper. The shock troops and militia had remained, and the Marines braced themselves, knowing what to expect.

The attack finally came, boiling out from among the ramshackle buildings and narrow streets and into open ground. The Marines had orders not to fire on civilian structures, but they had deployed a line of RS-14 picket ’bots fifteen hundred meters from the Marine perimeter. The baseball-sized devices had buried themselves in the sand and emerged now to transmit data on the range, numbers, and composition of the attacking force, and to paint larger targets, like trucks and hovercraft, with lasers.

With accurate ranging data transmitted from the pickets, Marines inside the perimeter began firing 20mm smartround mortars, sending the shells arcing above the oncoming charge, where they detonated, raining special munitions across the battlefield. Laser-homing antiarmor shells zeroed in on the vehicles. Shotgun fléchette rounds exploded twenty meters above the ground, spraying clouds of high-velocity slivers across broad stretches of the battlefield. Concussion rounds buried themselves in the sand, then detonated, hurling geysers of sand mixed with screaming, kicking bodies into the air.

Only one TAV was airborne at the moment. They were being kept up one at a time to conserve dwindling supplies of the liquid hydrogen used to fuel them. One was sufficient, however, to stoop like a hawk out of the sun, scattering a cloud of special munitions bomblets in a long, precisely placed footprint through the middle of the crowd. A truck and two hovercraft exploded, sending a trio of orange fireballs into the intense blue of the late afternoon sky.

All of the Marines along the northeastern sector of the perimeter were firing now, along with robot sentries and gunwalkers. Warhurst switched his weapon to burst fire; laser rifles had to recycle between each shot, so true full-auto wasn’t possible, but he could trigger up to six bursts at a cyclic rate of two per second before the weapon had to take a three-second pause to recharge. Another truck exploded.

Dozens of KOA troops were falling, caught in a devastating fire from the Marine positions and from directly overhead. The front ranks wavered, hesitating in the face of that deadly wind as those farther back kept pressing forward. In another moment the attack had dissolved into a bloody, thrashing tangle of people, some holding their ground, most trying desperately to flee to the rear and the imagined safety waiting for them back across the Nile.

“Cease fire!” Warhurst called over the command channel. “All squads, cease fire. They’ve had it.”

The attackers continued to flee, leaving several hundred dead and wounded in the desert; none had come within twelve hundred meters of the Marine lines. Most had fallen well beyond the range of their own weapons. No Marines had been hit.

“Good old Yankee high-tech scores again!” Private Gordon called over the tac channel. “They didn’t even touch us!”

“Belay the chatter,” Warhurst warned. “Keep alert. Petro? Anything in front of you?”

He had to assume that the brash, frontal rush had been a feint, something to pin the Marines’ attention to the northeast while the real attack was staged from another quarter.

“Negative, sir,” Gunny Petro replied. She was in charge of the northwest sector. “No targets.”

“Rodriguez?”

“All clear, Skipper.”

“Cooper?”

“Nothing on my front, sir.”

The robot sentries out in the desert were very sensitive, fully able to detect the approach of a single man by his body heat, his movement, his radar signature, even his scent. When Warhurst called up a tactical overhead view of the perimeter, he could see his own troops huddled in their fighting positions … but no sign of enemy troops closer than three kilometers.

But there would be another attack, and soon. He looked up into the early evening sky and wondered what the hell was happening to their relief.

Esteban Residence

Guaymas, Sonora Territory

United Federal Republic, Earth

1545 hours PT

“The Marines?” his mother cried. “Goddess, why would you want to join the Marines?”

John Garroway Esteban stood a little straighter, fists clenched at his side. “You had no right!” he said, shouting at his father, defiant. “My noumen is mine!”

“It’s my house, you’re my son!” his father shouted back, raging. The elder Esteban had been drinking, and his words were slurred. “I paid for your implant, and I can goddamn do anything in, to, or through your goddamn noumen I goddamn want!”

“Carlos, please,” John’s mother said. She was crying now. This was going to be a bad one.

They’d had this argument before, many times. John’s Sony implant created the inner, virtual world through which he could access the World Net, communicate with friends, and even operate noumenally keyed devices, from thought-clicked doors to the family flyer. Noumenon was the conceptual opposite to phenomenon; where a phenomenon was something that happened outside a person’s thoughts, in the real world, a noumenon was entirely a creation of thought and imagination, a virtual reality opened within his mind … but the one was no less real than the other. As the saying went, just because it was all in your head didn’t mean it wasn’t real.

It was also personal, keyed to John’s own thoughts and implant access codes. His father, however, insisted on supervising him through the implant, and the almost daily invasions of his privacy gnawed at John constantly.

Lots of kids had implants with parental controls, if only to monitor their study downloads and keep track of the entertainment Net sites they visited. Carlos Esteban went a lot further, eavesdropping on his conversations with Lynnley, reading his private files, and now downloading his conversation with the Marine recruiter three days ago. Every time John managed to assemble a counterprogram, like the yellow warning light, his father found a way around it … or simply bulled his way right in.

And his father was, of course, furious at his decision to join the Marines. He’d expected his father’s anger but had hoped his mother would understand. She was del Norte, after all, and a Garroway besides.

“No son of mine is going to be part of those butchers,” his father was saying. “The Butchers of Ensenada! No! I will not permit it! You will join me in the family business, and that is that!”

“I don’t want to be a part of the damned family business!” John shot back. “I want—”

“You are eighteen years old,” his father said, his voice rich with scorn. “You have no idea what it is you want!”

“Then maybe this is how I’ll find out!” He swung his arm angrily, taking in the quietly sophisticated sweep of the hacienda’s E-room and dining area, including the floor-to-ceiling viewall overlooking the silver waters of the Sea of Cortez below Cabo Haro. “I won’t if I stay here the rest of my life!”

A tone sounded. The house was signaling them: someone was at the door. He wanted to snatch the excuse, to pull up the visitor’s ID through his implant and go open the door … but his father was glaring into his eyes, furious, and the brief wandering of his thoughts would have been immediately noticed.

“You have here the promise of a good education!” Carlos continued, shouting. If he’d heard the announcement tone, he was ignoring it. “Of a place in the family business when you graduate. Security! Comfort! What more could you possibly need or want?” Carlos Jesus Esteban took another long sip from the glass of whiskey he held. He’d been drinking more and more heavily of late, and his temper had been getting shorter.

“Maybe I just want the chance to get those things for myself. To get an education and a job without having them handed to me!”

“Eh? With the Marines? What can they teach you? How to kill people? How to shed whatever civilized instincts you may have acquired and become an animal, a sociopathic murderer? Is that what you want?”

The house butler rolled in. “Excuse me,” it said. “There is—”

“Get out!” the elder Esteban screamed.

“Yes, sir.” Obediently, the robot spun about and glided out of the room once more, as though it was used to Carlos’s violent moods.

“You just want to go with those worthless gringo friends of yours,” his father continued. “You think military service is some sort of glamorous game, eh?”

“Have you thought about joining the Navy, Johnny?” his mother asked helpfully, with a worried, sidelong glance at his father. “Or the Aerospace Force? I mean, if you want to travel, to go offworld—”

“All of the services are parasites!” Carlos shouted, turning on her. “And the Marines are the worst! Invaders, oppressors, with their boots on our throats!”

“My grandfather was a Marine,” John said with more patience than he felt. “As was his father. And his mother and father. And—”

“All your mother’s side of the family,” his father snapped. He drained the last of his whiskey, then moved to the bar to pour himself another. He appeared to be calming down. His voice was quieter, his movements smoother. A dangerous sign. “Not mine. Always, it is the damned Garroways—”

“Carlos!” his mother said. “That’s not fair!”

“No? Please excuse me, Princessa del Norte! The gringos are always in the right, of course!”

“Carlos—”

“Shut up, puta! This worthless excuse for a son is your fault!”

The house had been signaling for several moments, first with an audible tone, then with a soft voice transmitted through John’s cerebral implants. No doubt the butler had been dispatched with the same warning: someone was still at the front door. A quick check with the house security camera showed him Lynnley Collins’s face.

Now might be his only chance.

“I’ll, um, see who’s at the door,” he said, and slipped as unobtrusively as possible from the room. His father was still screaming at his mother as he rode the curving line of moving steps from the E-center to the entranceway, alerting the house as he descended to open the door.

Lynnley was standing on the front deck, looking particularly fetching in a yellow sunsuit that bared her breasts to the bright, golden warmth of the Sonoran sun. Her dark-tanned skin glistened under her body’s UV-block secretions. Her eyes, with her sunscreen implants fully triggered, appeared large and jet-black.

“Uh, hi,” he said, slipping easily into English. Lynnley was the daughter of a norteamericano family stationed at the naval base up at Tiburón. She spoke excellent Spanish, but he preferred using English when he was with her.

She glanced past him as he stepped outside, brushing back a stray wisp of dark blond hair. The door hissed shut, cutting off his father’s muffled shouts.

“Whoo,” she said. “Bad one?”

He shrugged. “Pretty much what I expected, I guess.”

“That bad?” She touched his arm in sympathy. “So what are you going to do?”

“What can I do? I already thumbed the papers. We’re Marines now, Lynn.”

She laughed. “Well, not quite. There are a few minor formalities to attend to first. Like basic training, remember?”

He walked to the side of the deck, leaning against the redwood railing and staring out over the glistening waters of the Gulf of California. La Hacienda Esteban clung to the summit of a high hill overlooking the cape. The sprawl of the town of Guaymas, the harbor crammed with fishing boats, the clutter of resorts along the coast, provided a bright, tropical splash of mingled colors between the silver-gray sea and the sere brown of the hills and cliff sides. God, I hate it here, he thought.

“Having second thoughts?” Lynnley asked.

“Huh? Hell no! I’ve got to get out of here!”

“There are other ways to leave home than joining the Marines.”

“Sure. But I’ve always wanted to be a Marine. Ever since I was a kid. You know that.”

“I know. It’s the same with me. It’s in the blood, I guess.” She moved to the railing beside him, leaning against it and looking down at the town. “Is it just the Marines your dad hates? Or all gringos?”

“He married a gringo, remember. And she was a Marine’s daughter.”

“Hell, the war was over twenty years before he was born, right? What’s his problem?”

John sighed. “Some of the families down here have long memories, you know? His grandfather was killed at Ensenada. He doesn’t like the government, and he doesn’t like the military.”

“What is he, Aztlanista?”

“I don’t know anymore. Some of his drinking buddies are, I’m pretty sure. And I know he subscribes to a couple of different Aztlan nationalist netnews sites. He likes their ideas, whether he’s a card-carrying member or not.”

“S’funny,” Lynnley said. “Most of the Aztlanistas are poor working class. Indios, farmers. You don’t usually see the big landowners messing with the status quo, joining revolutionary organizations and all that.” She tossed her head, indicating the hacienda and the surrounding hilltop lands. “And your family does have money.”

He shrugged. “I guess. We don’t talk about where the money came from, of course.” His father’s family had become fabulously wealthy in the years before the UN War, when parts of Sonora and Sinaloa—then states of the old Mexican Republic—had furnished a large percentage of several types of illicit drugs for the huge and wealthy northern market.

“But it’s not just the money,” he went on. “There’s still such a thing as national pride. And all of the big-money families around here stand to come out on top of the heap if Aztlan becomes a reality. The new ruling class.”

“Huh. You think that could happen?”

“No,” he replied bluntly. “Not a snowball’s chance on Venus. But the possibility is going to keep the locals stirred up for a long time.”

Baja, Sonora, Sinaloa, and Chihuahua were the newest dependent territories of the burgeoning United Federal Republic, a political union that included the fifty-eight states of the United States plus such far-flung holdings as Cuba, the Northwest Territory, and the UFR Pacific Trust. Acquired during the Second Mexican War of ’76–’77, all four north Mejican territories were in line to be granted statehood, as the fifty-ninth through the sixty-second states, respectively, pending the outcome of a series of referendum votes scheduled in two years. Heavily dependent both on Yankee tourism and on northern markets for seafood and marijuana products, the region of old Mexico surrounding the Gulf of California had closer ties to the UFR than to the Democratic Republic of Mejico, and statehood was likely to pass.

But many in the newly acquired territories favored independence. The question of Aztlan, a proposed Latino nation to be carved out of the states of northern Mejico and the southwestern United States, had been one of the principal causes of the UN War of almost a century ago. The then–United Nations had proposed a referendum in the region, with a popular vote to determine Aztlanero independence. Washington refused, pointing out that the populations of the four U.S. states involved were predominantly Hispanic and almost certain to vote in favor of the referendum, and that federal authority superceded local desires. The war that followed had raged across the Earth, in orbit, and on the surfaces of both the Moon and Mars.

In the end, with the disintegration of the old UN and the rise of the U.S./UFR-Russian-Japanese–led Confederation of World States, Aztlan independence had been all but forgotten … save by a handful of Hispanic malcontents and disaffected political dreamers scattered from Mazatlan to Los Angeles.

The dream remained alive for many. John’s father, his family long an important clan with connections throughout Sonora and Sinaloa, had been more and more outspoken against the gringo invaders who’d migrated south since the Mexican War. “Carpetbaggers,” he called them, a historical allusion to a much earlier time.

But he’d not been able to convince John, and for the past four years their relationship, already shaky with Carlos’s drinking and his notoriously quick temper, had grown steadily worse.

“Have you ever thought,” Lynnley said quietly, “that you and your dad could end up on opposite sides, if fighting breaks out?”

“Uh-uh. Won’t happen. The government can’t use troops on federal soil.”

“A war starts down here, and all it would take is a presidential order. The Marines would be the first ones to go in.”

“It won’t come to that,” he said, stubborn. “Besides, I want space duty.”

She laughed. “And what makes you think they’ll take what you want into consideration?”

“Hey, they gave me a dream sheet to fill out.”

“So? I got one too, but once we sign aboard, our asses are theirs, right? We go where they tell us to go.”

“Yeah …” The idea of coming back to Sonora to put down a rebellion left him feeling a bit queasy. He thought he remembered reading, though, that the government never used troops to put down rebellions in the regions those troops called home. That just didn’t make sense.

It wasn’t going to come to that. It couldn’t.

“You need to get out of the house for a while?” Lynnley asked him. “I thought we might fly out to Pacifica. Maybe do some shopping?”

John glanced back at the front door. He could hear the faint and muffled echoes of his father, still shouting. “You stupid bitch! This is all your fault! …”

“I … don’t think I’d better,” he told her. “I don’t want to leave my mom.”

“She’s a big girl,” Lynnley said. “She can take care of herself.”

But she doesn’t, he thought, bitter. She can’t. He felt trapped.

After talking with the Marine recruiter over an implant link three days ago, he and Lynnley had gone to the Marine Corps recruiter in Tiburón the next day and thumbed their papers. In less than three weeks they were supposed to report to the training center at Parris Island, South Carolina. Somehow he had to tell his parents … his mother, at least. How?

More than once in the past few years, Ellen Garroway Esteban had left the man who was, more and more, a stranger. Two years ago John had tried to get between his parents when his father had been hitting his mother and he’d received a dislocated shoulder in the subsequent collision with a bookcase. And there’d been the time when his father chased her out of the house with a steak knife … and the time she ended up in the hospital, claiming to have fallen down the stairs. John had begged her to pack up and leave, to get out while she still could. Others had done the same—her sister Carol in San Diego, the social worker who’d counseled her after her stay in the hospital, Mother Beatrice, their priest. Each time, she’d agreed the marriage was unsavable and nearly left for good … but each time, she found a reason to stay or to come back home.

One day, John was terribly afraid, she was going to come back home and Carlos was going to kill her. It would be an accident, of course. Injuries he inflicted on others always were.

John hated the thought of leaving his mother, of just walking out and abandoning her. He felt like a coward for running away like this. At the same time, he knew there was nothing else he could do to help her. Goddess knew, he’d tried, but, damn it, she kept coming back, she refused to press charges, she covered up for her husband when the police showed up in response to his panicked calls, made excuses for his behavior: “Carlos is just under a lot of stress right now. He can’t help it, really …”

His mother would have to decide to help herself. He would be gone.

But not just yet. “No,” he told Lynnley. “You go ahead. I’d better hang around and see how this plays out.”

“Suit yourself,” she told him. “Just remember, you won’t be able to protect her when you’re with the Corps off on Mars or someplace.”

“I know.” Am I doing the right thing?

He wished there was an answer to that.