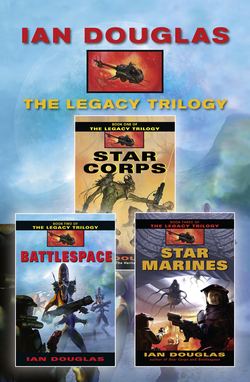

Читать книгу The Complete Legacy Trilogy: Star Corps, Battlespace, Star Marines - Ian Douglas, Matthew Taylor - Страница 19

11

Оглавление8 AUGUST 2138

Sick Bay

U.S. Marine Corps Recruit Training Center

Parris Island, South Carolina

1430 hours ET

“Garroway!”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“Through that hatch!”

“Aye aye, sir!”

Garroway banged through the door that had already swallowed half of Company 1099. Inside was the familiar, sterile-white embrace of seat, cabinets, AI doc, and the waiting corpsman.

“Have a seat,” the corpsman said. It wasn’t the same guy he had met in there before. What was his name? He couldn’t remember.

Not that it was important. New faces continually cycled through his awareness these days. Without his implants he could only memorize the important ones, the ones he was ordered to remember.

Of course, that was about to change now. He suppressed the surge of excitement.

“Feeling okay?” the corpsman asked.

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“No injuries? Infections? Allergies? Nothing like that?”

“Sir, no, sir!”

“Do you have at this time any moral or ethical problems with nanotechnic enhancement, implant technologies, or nanosomatic adjustment?”

“Sir, no, sir!”

The corpsman wasn’t even looking at him as he asked the questions. He wore instead the far-off gaze of someone linked into a net and was probably scanning Garroway now with senses far more sophisticated than those housed in merely human eyes or ears.

“He’s go,” the man said.

The AI doctor unfolded from the cabinet. One arm with an airjet hypo descended to his throat, and Garroway steeled himself against the hiss and burn of the injection.

“Right,” the corpsman said. “Just stay there, recruit. Give it time to work.”

This was it, at long last. It felt as though he’d been without an implant now for half his life, though in fact it had only been about six weeks. Six weeks of running, of learning, of training, all without being able to rely on an internal uplink to the local net.

It was, he thought, astonishing what you could do without a nexus of computers in your brain or electronic implants growing in your hands. He’d learned he could do amazing things without instant access to comlinks or library data.

But that didn’t mean he wasn’t eager to get his technic prostheses back.

Outside of a slight tingle in his throat, though, he didn’t feel much of anything. Had the injection worked?

“Okay, recruit. Off you go. Through that door and join your company.”

“Sir … I don’t feel—”

“Nothing to feel yet, recruit. It’ll take a day or two for the implants to start growing and making the necessary neural connections. You’ll be damned hungry, though. They’ll be feeding you extra at the mess hall these next few days to give the nano the raw materials it needs.”

He fell into ranks with the rest of his company and waited as the last men filed through the sick bay. Damn. He’d been so excited at the prospect of getting his implants that he’d not thought about how long it might take them to grow. He’d been hoping to talk to Lynnley tonight. …

He hadn’t seen her, hadn’t even linked with her, since arriving on Parris Island. Male and female recruits were kept strictly apart during recruit training, though he had glimpsed formations of women Marines from time to time across the grinder or marching off to one training exercise or another. The old dream of serving with her on some offworld station seemed remote right now. Had she changed much? Did she ever even think about him anymore?

Hell, of course she’s changed, he told himself. You’ve changed. So has she.

He’d been on the skinny side before, but two months of heavy exercise and special meals had bulked him up, all of the new mass muscle. His endurance was up, his temper better controlled, the periodic depression he’d felt subsumed now by the daily routine of training, exercise, and discipline.

And a lot of things that had been important to him once simply didn’t matter now.

He had been allowed to vid family grams to his mother, out in San Diego. She was still living with her sister and beginning the process of getting a divorce. That was good, he thought, as well as long overdue. There were rumors of unrest in the Mexican territories—Recruit Training Center monitors censored the details, unfortunately—and scuttlebutt about a new war.

He kept thinking about what Lynnley had said, back in Guaymas, about him having to fight down there against his own father.

Well, why not? He felt no loyalty to that bastard, not after the way he’d treated his mother. So far as he was concerned, he’d shed the man’s parental cloak when he’d reclaimed the name Garroway.

“Garroway!” Makowiecz barked.

“Sir! Yes, sir!”

“Come with me.”

The DI led him down a corridor and ushered him into another room with a brusque “In there.”

A Marine major, a tall, slender, hard-looking woman in dress grays, sat behind a desk inside.

“Sir! Recruit Garroway reporting as ordered, sir!” In the Corps, to a recruit, all officers were “sir” regardless of gender, along with most other things that moved.

“Sit down, recruit,” the woman said. “I’m Major Anderson, ComCon Delta Sierra two-one-nine.”

He took a seat, wondering if he’d screwed up somehow. Geez … it had to be something pretty bad for a major to step in. During their day-to-day routine, Marine recruits rarely if ever saw any officer of more exalted rank than lieutenant or captain. From a recruit’s point of view, a major was damned near goddesslike in the Corps hierarchy, and actually being addressed by one, summoned to her office, was … daunting, to say the least.

And a comcon? That meant she was part of a regular headquarters staff, probably the exec of a regiment. What could she possibly want with him?

“I’ve been going over your recruit training records, Garroway,” she told him. “You’re doing well. All three-sixes and higher for physical, psych, and all phase one and two training skills.”

“Sir, thank you, sir.”

“No formal marriage or family contracts. Your parents alive, separated.” She paused, and he wondered what she was getting at. “Have you given much thought yet to duty stations after you leave the island?”

That stopped him. Recruits were not asked to voice their preferences, especially by majors. “Uh … sir, uh … this recruit …”

“Relax, Garroway,” Anderson told him. “You’re not on the carpet. Actually, I’m screening members of your platoon for potential volunteers. I’m looking for Space Marines.”

And that rocked him even more. He’d wanted to be a Marine for as long as he could remember, true, ever since he’d learned about his famous leatherneck ancestors, but the real lure to the Corps had always been the possibility of offworld duty stations. The vast majority of Marines never left the Earth; most served out their hitches in the various special deployment divisions tasked with responding to brushfire wars and threats to the Federal Republic’s interests around the globe.

A very special few, however …

“You’re asking me to volunteer for space duty?” Excitement put him on the edge of the seat, leaning forward. “I mean, um, sir, this recruit thinks that, uh—”

“Why don’t we drop the formalities, John? That third-person recruit crap gets in the way of real communication.”

“Thank you, si—uh, ma’am.” He sighed, then took a deep breath, trying to force himself to relax. The excitement was almost overwhelming. “I … yes. I would be very interested in volunteering for a duty station offworld.”

“You might want to hear about it first,” she cautioned. “I’m not talking about barracks duty on Mars.” She went on to tell him, in brief, clipped sentences, about MIEU-1, a Marine expeditionary unit tasked with a high-profile rescue-recovery mission at Llalande 21185 IID, the Earthlike moon of a gas giant eight light-years distant.

“That’s where the human slaves are, right, ma’am?” he asked her. The newsfeeds had been full of the story around the time he’d signed up. The enforced e-feed blackout during his training period had pretty well cut him off from all news of the outside world, but there’d been plenty of rumor floating around the barracks for the past couple of months. “We’re going out there to free the slaves?”

“We are going to protect federal interests in the Llalande system,” she replied, her voice firm. “Which means we’ll do whatever the President directs us to do. The main thing you have to think about right now is whether you want to volunteer for such a mission. Objective time will be at least twenty years. Ten years out in cyhibe, ten back, plus however long it takes us to complete our mission requirements. Things change in twenty years. We won’t be coming back to the same place we left.”

That sobered him. His mother was, what? Forty-one? She’d be sixty-one or older by the time he saw her again. Regular anagathic regimens and nanotelemeric reconstruction made sixty middle age for most folks nowadays, but twenty years was still a hell of a chunk out of a person’s life. How much would he still have in common with any of the people he left behind?

“We’ll be in hibernation for the whole trip?”

“Hell, yes! That transport is going to be damned cozy for thirteen hundred or so people. We’d kill each other off long before we reached the mission objective if we weren’t. Besides, they wouldn’t be able to pack that much food, water, and air for that long a flight.”

“No, ma’am.” In a way, he was disappointed. Part of his dream included the thrill of the journey itself, flying out from Earth on one of the great interplanetary clippers or boosting for the stars on a near-c torchship.

Anderson was accessing some records with a faraway look in her eyes. “I’m checking your evaluations,” she told him. “Your DI thinks highly of you. Did you know you’re up for selection for embassy duty?”

“Huh? I mean, no, ma’am.” The way Makowiecz and the other DIs kept riding him, he’d not even been sure they were going to recommend him for retention in the Corps, much less … embassy duty? That was supposed to be the softest, best duty in the Corps, standing guard at the UFR embassy in some out-of-the-way world capital. You had to be absolutely top-line Marine for a billet like that, and be able to keep yourself and your uniform in recruiting poster form. But the duty was the stuff dream sheets were made of …

“It’s true,” she told him. “And I won’t bullshit you. The Ishtar mission is a combat op. We’ll be going in hot, weapons free, assault mode. The abos are primitive, but they have some high-tech quirks that are guaranteed to raise some damned nasty surprises. So … what’ll it be? A soft billet at an embassy? Or a sleeper slot and a hot LZ?”

He knew what he wanted. Plush as embassy duty was supposed to be, he’d always thought the reality would be boring. In fact, most duty Earthside would be boring, punctuated by the occasional day or two of truly exciting discomfort, pain, and fear during a combat TAV deployment to some war-torn corner of the planet. The Llalande mission might be hardship duty and combat, but it was offworld … as far offworld, in fact, as he was ever likely to get.

It would be what being a Marine was all about.

“Um, ma’am?”

“Yes?”

“I have a friend who joined up the same time I did. Recruit Collins. She’s in one of the female recruit training platoons.”

“And …?”

“I was just wondering if she was being asked to volunteer too, ma’am.”

“I see.” She looked thoughtful for a moment. “And that would determine your answer?”

“Uh, well …”

“John, you presumably joined the Corps of your own free will. You didn’t join because she joined, did you?”

“No, ma’am.” Well, not entirely. The idea of signing up together, maybe getting the same duty station afterward, had been part of the excitement. Part of the thrill and promise.

But not all of it.

“I’m glad to hear it. Contrary to popular belief, the Corps does not want mindless robots in its ranks. We want strong, aggressive young men and women who can make up their own minds, who serve because they believe, truly believe, that what they are doing is right. There is no room in my Corps for people who simply follow the crowd. Or who have no deeper commitment to the Corps than the fact that a buddy joined up. Do you copy?”

“Sir, yes … I mean, yes, ma’am.”

“I’m sure your DI has drilled this line into your skull, even without implants. The Corps is your family now. Mother. Father. Sib. Friend. Lover. In a way, you cast off your connections with everyone else when you came on board, as completely as you will if you volunteer for Ishtar and report on board the Derna for a twenty-year hibe slot. You will have changed that much. You’ve already changed more than you imagine. You’ll never go back to that old life again.”

“No, ma’am.” But he wasn’t talking about a civilian friend. Why didn’t she understand?

“And you also know by now that the Corps cannot be run for your convenience. Sometimes, like now, you’re given a choice. A carefully crafted choice, within tightly defined parameters, but a choice, nonetheless. You must make your decision within the parameters that the Corps gives you. That’s part of the price you pay for being a Marine.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“So. What’ll it be? I can’t promise you’ll end up stationed with Recruit Collins, no matter what you decide. No one can. The question is, what do you want for yourself?”

He straightened in his chair. There still was no question what he wanted most. “Sir, this recruit wishes to volunteer for the Ishtar billet, sir,” he said, slipping back into the programmed third-person argot of the well-drilled Marine recruit.

“Very well, recruit,” Anderson replied. “No promises yet, understand. We’re still just screening for applicants. But if everything works out, and you complete your recruit training as scheduled, it will be good to have you on board.”

“Thank you, sir!”

“Very well. Dismissed.”

“Aye aye, sir!”

He rose, turned, and banged through the door, scarcely able to believe what had happened.

The stars! He was going to go to the fucking stars! …

Headquarters, PanTerra Dynamics

New Chicago, Illinois

United Federal Republic, Earth

1725 hours CT

“PanTerra Dynamics is going to the stars, gentlemen,” Allyn Buckner said. “We have personnel on our payroll on the Derna, and they will be on Ishtar at least six months before you. Now … you can work with PanTerra, or you can be left out in the cold. What’s it going to be?”

The virtual comm simulation had them standing in a floating garden, high above the thundering mist of Victoria Falls, in the Empire of Brazil. The building actually existed—a combination of hotel, conference center, and playground for the wealthy. Terraced steps, sun-sparkling fountains, riotous tangles of brightly flowering greenery to match the remnants of rain forest around the river below, Orinoco Sky was an aerostat city adrift in tropical skies.

Buckner, of course, was still in New Chicago. His schedule hadn’t allowed him the luxury of attending this conference in person. In fact, perhaps half of the people in the garden lounge in front of him were there in simulacra only. Haddad, he knew, was still in Baghdad, and Chieu was linking in from a villa outside of Beijing.

Through the data feeds in their implants, however, each of the conference attendees saw and heard all of the others, whether they were in Orinoco Sky in the body or in telepresence only.

Buckner was glad he was there in virtual sim only. The decadence of the surroundings fogged the brain, sidetracked the mind. It was easier to link in for the meeting he’d called, get the business over with, and link off, all without leaving the embrace of the VR chair in his New Chicago office.

For one thing, it meant he could cut these idiots off if they imposed on his time.

“You Americans,” Haddad told him with a dark look. “For a century you’ve acted as though you own the Earth. Now you are laying claim to the stars as well. You should remember that Allah is known for bringing down the proud and arrogant.”

“Don’t lecture me, Haddad. You’re lucky even to be here, after that business the KOA pulled in Egypt.” He grinned mirthlessly. “Besides, I thought you Mahdists didn’t believe in the Ahannu.”

“Of course we believe in them.” He gave an eloquent shrug. “How could we not? They are there, on the Llalande planet, for all to see. We do not believe, however, that they are gods. Or that they shaped the course of human destiny. Or that they … they engineered us, as some ignorant people, atheists, suggest.”

“Our friends in the Kingdom of Allah are not the blind fanatics you Americans believe them to be,” Dom Camara said. “They are as practical, and with as keen a sense of business, as we here in the Brazilian Empire. Your scheme could upset the economies of many nations here on Earth. We wish to address that.”

“You want to be in on the distribution of goodies, is what you mean,” Buckner said. “I can accept that. But PanTerra is going to be there first. That means you play by our rules.”

“And what, precisely,” Raychaudhuri asked, “are the rules, Mr. Buckner?”

“PanTerra Dynamics will be the authorized agent for Terran economic interests in the Llalande system. All Terran economic interests. We welcome investment on Ishtar, but the money will go through us. We expect, in time, to form the de facto government on Ishtar.”

Camara chuckled. “Mightn’t the abos have something to say about that?”

Buckner made a dismissive gesture. “That’s what the American Marines are for,” he replied. “The human slavery issue has all of North America ready to kick the Ahannu where it hurts most.”

“What do you mean?” Koslonova, of Ukraine, said. “You’re saying the Marines are going to wipe out the Ahannu?”

Buckner smiled at her. “That, of course, would be the ideal.”

Pelligrini, one of the other Euro-Union representatives, looked shocked. “Signor Buckner! You are talking about annihilating the population of a planet!”

“Calm yourself, Aberto. I said that would be the ideal, from our perspective, but we are realists. The MIEU will only have about a thousand Marines or so, and Ishtar is a world, a damned big place. They wouldn’t be able to wipe out something like ten million aborigines all at once. Hell, even if they could, public reaction back on home would be … counterproductive.

“But we do see the game playing out like this: we all know they won’t find any of our people alive when they get there, not after ten years. The Marines will have to assault the Legation compound and, of course, secure the Pyramid of the Eye to reestablish real-time communication with Earth. The Frogs, the abos, are practically stone age, but they’re tenacious little bastards. They’ll put up a fight. The Marines will have to smash them down pretty hard in order to regain control.

“Once the local government is forced to see reason, our people will form an advisory council and oversee the creation of a new abo government. We can expect the defeat of the current government to result in the surfacing of lots of new factions, and we’ll selectively help those factions who go along with our plans for Ishtar. Within two years, three at the most, we should have a functioning Ahannu government in place, one completely friendly to PanTerran interests and compliant to the directions of our representatives. And, of course, the Marines will be there to provide the stick behind PanTerra’s carrot.”

“The gwailos of the western world followed a similar policy once on the shores of the Middle Kingdom,” Chieu said quietly. “The end result was revolution, economic ruin, the collapse of empires, and unspeakable human suffering. Do you really expect your policies on Ishtar to have any different outcome?”

Buckner wasn’t sure at first what Chieu was talking about. He thought-clicked through some download references, pausing just long enough to confirm that the Hegemony’s representative was referring to the virtual land rush in China during the nineteenth century. Hong Kong. Macao. The Opium Wars. The Boxer Rebellion. A dozen nations had staked claims to various trading ports along the Chinese coast, intervening in Chinese affairs, forcing China to trade with the foreigners and on the foreigners’ terms.

“Mr. Chieu, PanTerra has already invested heavily in the development of our franchise on Ishtar. We wish only to see a return on that investment. Frankly, when Ishtar ceases to be a profitable venture, we will be quite happy to return full control of Ishtaran affairs back to the Ahannu. In the meantime, we offer the aborigines peace, technical advancement, the advantages of technic civilization in so far as they’re able to handle them, and stability. Think of it! Ahannu culture has advanced scarcely at all since the collapse of their interstellar empire ten thousand years ago. Within a few generations, they could undergo an industrial revolution and even contemplate a return to space.”

“It’s not like PanTerra to encourage potential competitors,” Camara said. His smile robbed the words of their edge.

“Not competitors,” Buckner said. “Trade partners. Business partners. The point is, all of that won’t happen for a century or two. We don’t need to worry about it. All we need do is think about the money we’re going to make from this one investment!”

“Yes,” Haddad said. “Money. A return on your investment. I believe I speak for a number of us here when I say that your scheme for using the human slaves on Ishtar as an additional return on your investment … this has a very foul smell to it. Am I to understand that PanTerra intends to import slaves, human slaves, from Ishtar? That you intend—if I understand this correctly—to use a campaign to free those slaves, only to ship them back to Earth for use as slaves here?”

“Please, Mr. Haddad,” Buckner said with a pained expression. “We prefer the word ‘domestics.’ Not ‘slaves.’ There are entirely too many negative connotations to that word.”

“Whatever you choose to call it,” Haddad said, pressing on, “the concept is neither moral nor economically viable.”

“Representative Haddad has a point,” Chieu said. “The population of Earth would never accept such a moral outrage.”

Buckner scowled at the assembly. “You want to lecture me on morality? You, Haddad—when for at least the past two hundred years or more your upper classes have imported domestic servants from various parts of Asia and Pacifica and paid them so poorly they cannot return home if they wish? When pockets of outright slavery still exist throughout the KOA in places like Sudan and Oman, and when women still have fewer rights than male slaves?”

“We are all slaves of Allah—” Haddad began.

“Can the sermon. I worship at a different church, the Church of the Almighty Newdollar.” Haddad bristled, but Buckner raised a hand. “Please. I mean no disrespect to anyone here. But it does give me a tremendous pain when people start making a major bleeding poor-mouth about moral outrages when it’s their comfort and their security and their wealth that they’re really concerned about. I don’t like hypocrisy.”

“According to the report you’ve uploaded to us,” Raychaudhuri said evenly, “you plan to partly defray PanTerra’s development costs on Ishtar by bringing freed human Sag-ura back to Earth and selling them as servants. If that, sir, is not hypocrisy—”

“And in your country, Raychaudhuri, a poor man can still sell his daughters,” Buckner said. “But that’s not the point, is it? Everything depends on how it is packaged. You’ve seen PanTerra’s reports … in particular, the reports on these Sag-uras. For ten thousand years they’ve been raised, been bred, as slaves to the Ahannu. They think of the Ahannu as gods … would no more think about disobeying them than you, Mr. Haddad, would think about disobeying Allah. They are conditioned from birth to accept the living reality of gods who direct every part of their lives.

“And now, we’re going to arrive there, backed up by the Marines, and stand their world on its ear. What do you think would happen if we just walked in, gathered up all the Sag-ura, and said, ‘Congratulations, guys. You’re free.’ Hell, they’d starve to death in a month! They don’t even have a word in their vocabulary that means ‘freedom’! Like Orwell pointed out a couple of centuries ago, you can’t think about something if you don’t have a word for it.

“At the same time, we have half the people on Earth clamoring for their release. ‘Humans being held in slavery by horrible aliens! Oh, no! … We must set things right, must free those poor, wronged innocents from their bondage!’

“So PanTerra is proposing a social program that will satisfy the people of Earth, help the Ishtaran humans, and, just incidentally, help PanTerra recover what we’ve put into this project. As we send interstellar transports filled with Marines, scientists, and researchers out to Ishtar, we will begin bringing back transport loads of ex-slaves. They will be reintegrated slowly and carefully into human society. They do not understand the concept of ‘money’ or ‘payment’ or ‘salary,’ so they will be hired out to people willing to provide them with room and board in exchange for their domestic services.

“Status, my friends, is an important coin in human relations. The upper classes on Earth of nearly every culture still derive considerable status from the employment of human servants. And, as they used to say, good servants are so hard to find. Well, PanTerra has found the mother lode of domestic servants. Happy, healthy, beautiful people conditioned to take orders and provide service because that’s the way they were raised, because that’s the only thing they know. And those Sag-ura who are shipped back to Earth, I might add, will derive considerable status from the mere fact of being chosen to return to the fabled home planet. And they will have the chance to slowly assimilate into Earth-human culture.

“And if PanTerra charges for providing this service … what of it? People, don’t you see? Everybody wins! You. The Sag-ura. And PanTerra.”

“Mr. Buckner,” Chieu said, “I thought PanTerra’s sole interest in Ishtar was the possibility of acquiring alien technology?”

Buckner nodded. “It’s our interest, certainly. Not our sole interest, but an important one. We expect to reap enormous profits from our research on Ishtar. The greatest profits of all may well come from aspects of their history and technology and biology and culture yet to be uncovered, things that we’re not even aware of yet. But that is all so speculative at this point, it would be insane to count on that to balance the accounts. We know we will make a profit by bringing a few thousand Sag-ura back to Earth and acting as agents on their behalf. Anything else is, as they say, gravy.”

The French representative, Xarla Fortier, folded her arms, radiating disapproval. “What arrogant assumption, monsieur, gives you the right to dictate this way to us? Ishtar, its wealth and its lost knowledge, should be the inheritance of all of humanity, not the playground of a single corporate entity! What you propose is nothing less than the wholesale rape of an inhabited world, to your benefit.”

“Worse, Madame Fortier,” Raychaudhuri said, “he proposes to let us watch but not participate. PanTerra intends nothing less than a complete monopoly over Ishtar and all her products, subsidized by the United Federal Republic and backed by the muscle of the U.S. Marines. I, for one, protest.”

“Tell us, Mr. Buckner,” Chieu said, eyes narrowing to hard, cold slits, “what happens if the population of Earth at large gets wind of this scheme of yours? You realize, of course, that any one of us here could upset your plans simply by net-publishing your report.”

“Is that a threat, Mr. Chieu?” Buckner sighed. “I’d thought better of you. Each and every one of you answers to your own corporate interests. You will need to consult with them before taking such an irretrievably drastic step … one, I might add, that would reveal your own complicity in these deliberations. PanTerra would respond as necessary to minimize the damage, to put a good spin on things. We would emphasize the benevolent nature of our business dealings on Ishtar, the great public good we were providing. Even slavery, you see, can be presented as good, as a social or an economic or a religious necessity, if there is a carefully nurtured will to believe. … Am I correct, Mr. Haddad? True, our profits might be adversely impacted to some degree, but I doubt there would be major problems in the long run.

“Of course, whoever leaks that information would find their corporate interests cut off from the deal. My God … we’re not leaving you out. We’re making you our partners! Secrecy, you see, is more in your interests than in ours. Play along, and each of you becomes the sole agent for the distribution of what we bring back from Ishtar to your own countries. New science. New knowledge. New medicines, perhaps, or new outlooks on the universe. And, of course, the chance to offer Ishtaran domestics to the upper strata of your populations, at a very healthy profit for yourselves.

“Mr. Chieu, why would you possibly want to jeopardize that for yourself or the people of the Chinese People’s Hegemony?” He shrugged. “You all can discuss it as much as you want. Take it up with the Confederation Council, if you like. The simple fact is, PanTerra will be at Ishtar six months before the joint multinational expedition gets there. And I happen to know that the Marines will have orders not only to safeguard human interests on the planet, but to safeguard Confederation interests as well … and that means UFR interests, ladies and gentlemen. PanTerran interests. I tell you this in the hope that we can avoid any expensive confrontations, either here or on Ishtar.” He spread his hands, pouring sincerity into his voice. “Believe me when I say we want a reasonable return on our investment—no more. PanTerra is not the evil ogre you seem to believe it is. We are happy to share—for a fair and equitable price. Ishtar is a planet, a world, with all of the resources, wonders, and riches that a planet has to offer, with fortunes to be made from the exchange of culture, philosophy, history, knowledge.”

“And if anyone can put a price tag on that knowledge,” Haddad said wryly, “PanTerra can. Friends, I think we have little alternative, at least for now.”

“I agree,” Fortier said. “Reluctantly. We don’t have to like it. …”

“We understand the need for secrecy, Señor Buckner,” Dom Camara said. “But how can you guarantee that word of this—this plan of yours will not leak anyway? You can threaten to cut us off from our contracts with you … but not the Marines. Or the scientists.” Camara cocked his head to one side. “This civilian expert you’ve hired … Dr. Hanson? Suppose she doesn’t go along with your ideas of charity and enlightenment for the Sag-ura?”

“Dr. Hanson is, quite frankly, the best in the field there is. We brought her on board to help us identify and acquire xenotechnoarcheological artifacts that may be of interest. She is a PanTerran employee. If she doesn’t do her job to our satisfaction, we will terminate her contract.”

He didn’t elaborate. There was no reason to share with these people the darker aspects of some of the long meetings he’d held here in New Chicago with other PanTerran executives. The truth of it was that anyone who got in PanTerra’s way on this deal would be terminated.

One way or another.

“And the Marines?” Camara wanted to know.

“They work for the FR/US government, of course, and are not, as such, directly under our control. They will do what they are sent out there to do, however. And we have taken … certain steps to ensure that our wishes are heard and respected.

“Believe me, people, we are not monsters. We are not some evil empire bent on dominating Earth’s economy. What we at PanTerra are simply doing is ensuring that there is not a mad scramble for Ishtar’s resources.” He cocked an eye at Chieu. “We certainly do not want an unfortunate repeat of what happened in China three centuries ago, with half the civilized world snapping like dogs at a carcass. We propose order, an equitable distribution of the profits, and, most important, profits for everyone.”

“Including the Ahannu, Mr. Buckner?” Chieu asked.

“If they choose to accept civilization,” Buckner replied, “of course. They cannot wall off the universe forever. But as they adopt a less hidebound form of government, a freer philosophy, they will benefit as our partners and as our friends.” He was quite sincere as he spoke.

He almost meant everything he said.