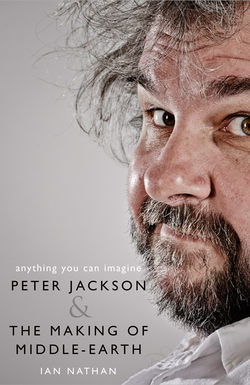

Читать книгу Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth - Ian Nathan - Страница 12

CHAPTER 4 Words and Pictures

ОглавлениеWhen Philippa Boyens was twelve years old her mother presented her with a copy of the book that would change her life. She was partial to a vein of old-school, romantic fantasy, inspired by her time spent at school in England. Between terms, her family would tour the country locating the fabled seats of Arthurian history. Myths and legends fired her imagination.

Nevertheless, moons would wax and wane while The Lord of the Rings stared at her from the shelf, untouched. She had enjoyed The Hobbit, but she was wary of the sheer volume of its grown-up brother. Venture within those pages and she might never come out. Which, you could say, is exactly what happened.

‘I’ve got this memory of my sister having swimming lessons,’ she says, ‘and me sitting in the car and deciding, ‘“Okay, I’m going to start reading this thing.”’

It was like taking a deep breath then diving in.

‘Then I read it every year. I’m not joking, every year. It was my rainy day book.’ There were many wet afternoons in the New Zealand she returned to as a teen.

Boyens had loved C.S. Lewis’ Narnia novels, fleet and quixotic, with evacuees finding snow-dusted enchantment at the back of a wardrobe. But Lewis wasn’t an obsessive like Tolkien. That is what moved her so deeply. How you could keep delving and there would always be another layer beneath. She lapped up the genealogy, the languages, how every person or place or antique artefact was reinforced in the appendices, and this great legendarium linked together like history.1 Only Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea novels came close.

She might refute the label of Tolkien expert that is regularly foisted upon her — often by a director swerving a tricky question. ‘I’m not an expert. I’ve met Tolkien experts. I can’t speak Elvish.’ Even so, while a teen, Boyens read Humphrey Carpenter’s eloquent biography of Tolkien, high-minded appreciation by David Day and Tom Shippey and the low-minded parody of The Harvard Lampoon’s 1969 Bored of the Rings, featuring Frito Bugger and Gimlet son of Groin. She would bring to the films an invaluable depth of knowledge and near-photographic recall of the professor’s sub-creation. She also had a real thing for the art of Alan Lee.

Her mother, that singular influence, had given her a copy of Lee’s seminal collection Faeries, a gift she passed on to Jackson. There was an illustration of a ‘Gandalf-like character’ that, she says, ‘really lit Pete’s radar’.

What she had resolutely not done was watch Ralph Bakshi’s half-grown adaptation. On this she was adamant, no one could possibly do justice to the book on film.

In early 1997, Stephen Sinclair was helping Jackson and Walsh fathom how to do just that. While a fine dramatist, who had read the books as a kid, Sinclair was no expert and had no intention of changing that fact. He took what Jackson called a ‘cavalier’ attitude toward the text. However, Sinclair‘s girlfriend, a playwright, teacher, editor and director of the New Zealand Writer’s Guild, definitely knew a thing or two about Tolkien.

Boyens can remember the night Jackson and Fran Walsh first called, wondering if he might join their new project. She was in the kitchen when Sinclair got off the phone.

‘Oh my God,’ he said. ‘You’ll never guess what Fran and Pete are working on next.’

‘I have no idea.’

‘It’s The Lord of the Rings.’

Boyens was incensed. ‘Well, they can’t. That’s crazy. No one can make that film.’

With her deep red, disobedient locks, often shored-up beneath a hat, Boyens cultivates a bohemian air much like her close friend Walsh. The two women who work so closely with Jackson have an aura of the otherworldly about them, as if they already had one foot in Middle-earth. Cloaked in her softly Gothic selection of floor-length dresses and shawls, you might suspect Boyens of being a modern-day sorceress. That is until you get a taste of her earthy Kiwi humour and logical mind. Like her partners, she has little time for the platitudes of Hollywood. There is an undercurrent of conviction to her mellifluous, Kiwi accent that is ironclad.

When Sinclair showed Boyens the treatment, she came back with notes. ‘Just ideas about the story,’ she vows. Initially, all Jackson and Walsh knew of Sinclair’s bookish partner who would alter the course of their creative lives were the incisive despatches that arrived from Auckland via Sinclair (Boyens also unofficially assisted Sinclair in writing some ‘romantic’ elements while he was still involved in The Lord of the Rings), until, intrigued, they invited her down to Wellington. After ten minutes of effusive icebreaking over how impressed she had been by their treatment, she got on to its shortcomings. Which turned out to be the interesting part. If there were things she felt they had done wrong — and there were more than a few — she had a solution for each one.

Boyens emphasized that it was critical to still recognize this as The Lord of the Rings within the landscape of the film. It had been an almost counterintuitive experience, assessing the book as a film, prompting an internal debate with her old self. Knowing in her heart that you can’t do The Lord of the Rings without Tom Bombadil and the Old Forest, but in her head understanding that you have to. Boyens found that she was able to think ruthlessly in film terms.

Impressed, Jackson and Walsh pushed for her active involvement. Meanwhile Sinclair’s interest had begun to wane as he itched to return to his plays and novels. The enormity of the project was too much of a commitment. ‘He looked at one draft,’ confirms Jackson. ‘But he was involved for literally a few weeks.’ Sinclair was recognized with a credit on The Two Towers, where his contribution was most manifest.

Thus it was Boyens who became the third voice in a screenwriting fellowship. She admits to feeling ‘terrified’ at first. This was her precious The Lord of the Rings; it still felt crazy to be even thinking of turning it into a film. But this was an offer to be at the heart of the craziness. To live and breathe Tolkien in a completely new way. How could she say no?

Before she met them, Boyens had been avidly following Jackson and Walsh’s blossoming career. She thought Braindead was genius. She was in the audience at the New Zealand Awards when Heavenly Creatures won everything only to be denied Best Film. ‘I felt like, God, New Zealand film needs to grow up. It felt so small and insular, and Fran and Pete have always looked outwards.’

That sense of adventure was infectious.

‘The biggest issue was always how do you get into this story?’ Boyens had written plays and dealt with screenwriters, but never attempted a screenplay herself. She was hired first as a script editor on the two-film draft, which was still in need of a prologue. So she volunteered to try and write one. The very first thing she officially set to paper was the opening line, ‘The world has changed …’ Over the arduous months that became years of interminable rewrites and restructuring of ultimately three-intertwined, award-strewn scripts, that line never changed.

*

‘The most difficult thing on this project has been the script. The script has been a total nightmare.’ Jackson was speaking in Cannes in 2001, where he had unveiled twenty-six minutes of footage to raptures from the world’s press. The question of how one successfully adapts Tolkien had come up frequently. Something he had been doing his level best to answer for six years.

He mused that it was about getting the balance right. To have the characters represent both Tolkien’s intentions and be accessible for a modern cinema audience who didn’t have a clue about hobbits or Elves. ‘It’s about trying to please as many people as possible,’ he explained, which he knew sounded horribly general. ‘But to reach people,’ he insisted, ‘you have to start by pleasing yourself. And that is what I did. I thought simply of the film I dreamed of seeing.’

Costa Botes has a memory of seeing the script for Bad Taste. Or the lack of it — it was little more than lines scribbled on increasingly crumpled pieces of paper in biro. Jackson had had no idea how to write a formal script. Walsh at least had some experience writing for television. ‘But both of them got religion when Robert McKee made a rare excursion to Wellington and they attended his seminar.’

McKee was the Detroit-born playwright and screenwriter turned hugely influential creative screenwriting guru touring the world with his famous Story Seminar. He preached a gospel that it was narrative structure that made a story compelling rather than any of its component pieces: plot, dialogue, characters, etc. You must tell a story.

Enlightened, Jackson and Walsh changed their entire approach to screenwriting. Out of which came Meet the Feebles, Braindead — which for all its gore is elegantly structured — and, in time, their Planet of the Apes and Freddy Krueger scripts. Says Botes, ‘I remember Pete showing me the third draft of Heavenly Creatures. It’s a masterpiece. That’s an unbelievable development in a very short space of time.’

Deep-rooted into Jackson’s philosophy of filmmaking was the certainty that he, alongside Walsh, would always generate the screenplay. Writing and shooting were stages on the same journey. This is one of the reasons he could hold three films in his head at one time — the scripts were ingrained.

From the moment he reread The Lord of the Rings, however, it was clear McKee’s principles would be put to a severe test. Tolkien had taken seventeen years to write the damn thing. It was dauntingly complex. Jackson and Walsh had to go back over and over things — ‘assembling it in their heads’ — seeing how it all connected, figuring out what made this book they had fought doggedly to adapt so adored? More to the point, what, if anything, made it cinematic?

*

The Book: The debate over the relative literary merits of Tolkien’s great opus has raged since its publication. There is no arguing that a vast readership is devoted to the point of religious fervour. Indeed, this intense popularity is partly what inflames the literati. Why can’t it just be forgotten? They would surely miss it if it were to pass out of fashion. They make such sport out of mocking the book. The aforementioned Edmund Wilson surmised that ‘certain people — especially, perhaps, in Britain — have a lifelong appetite for juvenile trash’. The general tenor of literary disgust aggregates around its supposed childishness and lack of moral depth, irony, theme or allusion.

When it was crowned ‘the greatest book of the century’ by a public poll in 1997 the journalist Susan Jeffreys led a chorus of snobby intellectuals in a familiar song. Writing in The Sunday Times, she feared she might actually catch something from the book. ‘I won’t keep the thing in the house,’ she insisted. For the article, she had borrowed a copy and complained about its ‘stale, bedsittish aroma’. Ultimately, she found it depressing to find so many readers ‘burrowing an escape into a non-existent world’ and its popularity proved ‘the folly of teaching people to read’.

There is no doubt of Tolkien’s appeal to readers of a certain age. This might in part be about escapism. Neil Gaiman, the celebrated fantasy author, recalled that at fourteen all he wanted to do was write The Lord of the Rings. Not the equivalent high fantasy, but the actual book. Which was awkward, he admitted, as Tolkien had already done so.

But Jeffrey’s ‘non-existent’ feels underpowered. Tolkien is far from divorced from the real world.

Yes, the story does transport people. The wonderful, unquenchable invention that sheers off every page is intoxicating. ‘It is a really exceptional and remarkable creation, an entire cosmology in itself,’ enthused actor John Rhys-Davies, who had long considered the book beneath him. This has led to obsession, if not addiction. Jackson and Walsh were keenly aware that they needed to escape the closed feedback loop of Tolkien fixation. In this, their relative ambivalence toward the text to begin with was an advantage.

Nevertheless, re-reading The Lord of the Rings through a cinematic lens revealed a store of promise for the filmmakers.

In 1938, Tolkien gave a lecture at the University of St. Andrews in Fife, Scotland, in which he highlighted the necessary components of ‘the office of fantasy’. A fantasy world, he insisted, while ‘internally consistent’ must possess ‘strangeness and wonder’. It must have a freedom from observed fact. The laws of physics while largely upheld can be a tiresome constraint on mythical storytelling. Quite how Sauron has uploaded a crucial portion of his malign life force into a golden ring is not worth deliberating. Above all, he declared, the secondary world must be credible, ‘commanding belief’.

Tolkien was not shy about the fact he had fashioned Middle-earth from the forges of history. This wasn’t an alternative universe but our own. Richard Taylor fixates with great pleasure on the estimation that the story can be located to an interglacial lull in the Pleistocene. Are we to consider the mûmakil relations of mammoths? Are the fell beasts a species of Pterodactyl?

It is a perspective somewhat undone by the Edwardian trappings of Hobbiton, although Jackson describes it as ‘a fully developed society and environment the records have since forgotten.’

Within the fabric of the world and the weft of the storytelling came Tolkien’s firm instruction to Jackson — command belief.

And contrary to critical opinion, the book possesses a rich seam of theme and allusion. This was something the arrival of Boyens really brought home. She educated her partners in what lay behind the book that Jackson admits they ‘really hadn’t grappled with’. A depth, she felt, that would elevate their films above the gaudy clichés of the barbarian hordes.

Says Jackson, ‘We hadn’t understood that he cared passionately about the loss of the natural countryside, for example. He was very much this nineteenth century, pre-Industrial Revolution guy against the factories and the enslavement of the workers in factories. Which is what Saruman is all about.’

Tolkien’s experiences on the Somme pierce the book. It was something to which Jackson, the First World War scholar, really responded. The Dead Marshes, depicting an ancient battleground swallowed up by the earth, are a striking vision of bodies lurking beneath the characters’ feet like no man’s land. The book is transfixed by death. While in counterpoint it portrays loyalty and comradeship in extremis. The Fellowship isn’t only a mission; it is the philosophy that might save them. And in Frodo and Sam the idea of comradeship crosses boundaries of class much as Tolkien had witnessed in the Great War.

The critic Philip French found it telling that Tolkien ‘made the object of Frodo’s journey not a search for power but its abnegation’. Ironically, for all its Elves, Dwarves and hobbits, the book’s humanity makes it timeless — applicable to any age, any war. It remains relevant.

Tolkien’s writing can be archaic (he was creating a mythology; you can take or leave the songs) but he had an intuitive grasp of a set piece modern studios would die for: the Ringwraiths attacking Weathertop; Gandalf confronting the Balrog; the Ents demolishing Isengard; Shelob’s Lair. It was a menu of choice, cinematic dishes.

Jackson appreciated how Tolkien’s writing so vividly describes things: ‘You can imagine a movie: the camera angles and the cutting, you see it playing itself out.’

Ordesky admired how the story expands in a natural way. From the Shire, the world unfolds, getting larger and larger.

And at heart it was a relatively linear story. The unlikeliest of heroes, knee-high to a wizard, must sneak into the enemy’s camp and destroy their most powerful weapon right beneath their nose (or Eye). Keeping the focus on Frodo’s quest, aided and abetted by a disparate group of individuals, would give the films forward momentum. Through a very distorted lens, here was Bob Weinstein’s fucking Guns of Navarone.

So it didn’t take long to conclude that Tom Bombadil was surplus to requirements. Tolkien had started writing his sequel to The Hobbit without a clear sense of direction. The first few chapters charting the hobbits’ flight from The Shire don’t really cohere until they get to Bree and Strider. Preserving Bombadil, an ambiguous eco-bumpkin-cum-forest spirit immune to the Ring, would only waylay the drama and diminish the authenticity of the world at a critically early stage, no matter how many fans clamoured for Robin Williams to supply the babbling brook of his rustic banter.

‘He was never in the script at any point,’ asserts Jackson.

The question of Bombadil, so easily answered, signalled that key debate: how faithful they were going to be. Something they would begin to fathom with a treatment.2

*

The Treatment: As their initial canary in the cage sent into the Mines of Moria, Botes’ scene-by-scene breakdown provided the basis for a ninety-two-page treatment for the two-film screenplay, clarifying Tolkien’s 1,000-page edifice into 266 sequences. A document that reveals how the backbone of the eventual trilogy was established very quickly, and where there was still considerable uncertainty.

While the detail is inevitably sketchy, the shape and tone of book are clearly intact. This was not the lightheaded remix embarked upon by John Boorman. The first film would end shortly after Helm’s Deep with the death of Saruman (eventually postponed all the way to the extended edition of The Return of the King), the second picking up immediately in the wake of battle. Many of the scenes are already determined, especially for what were eventually the first and third films. There are fewer major omissions than you might imagine: Lothlórien is the biggest absentee, while Edoras gets only a fleeting visit.

What impresses is how much of Jackson’s vision already emerges so quickly. The opening scene is a ‘breathtaking vista of battle’ with 150,000 Orcs, Men and Elves on screen. He is already inventing signature shots. With Radagast eliminated (until The Hobbit) the great eagle Gwaihir is sent to rescue Gandalf from Orthanc by the intercession of a moth. An idea which just ‘popped’ into Jackson’s head simultaneously with the image of the camera plummeting over the edge of the tower, down its vertiginous flank and into the quasi-industrial pits of Isengard.

Here is both the train of events and the visual language with which he would depict Middle-earth, giving the camera a panoptic viewpoint, swooping and plunging across the landscape indeed like an eagle. For instance, from the moment he re-read the book the siege of Minas Tirith clanged within his eager imagination: ‘Thousands of FLAMING TORCHES light the snarling, slathering ORCS. DRUMMERS are beating the DRUMS OF WAR …’

*

The Two-film Version (with Miramax): For all his many gifts, Tolkien presented pitfalls for a future screenwriter. The sheer multitudinousness of his sub-creation would always have to be tamed — a landslide of material artfully removed while remaining tangibly Tolkien — but the story is also awkwardly episodic and repetitious. ‘You kind of don’t notice it when you fall into the world of the books,’ groans Boyens. ‘But boy, you notice it when you have to bring it to screen.’

There are dramatic cadences that would have McKee wielding his red pen in fury. As Jackson bewails, the good guys ‘need to lose’ the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Tolkien has to rustle up a further clash at the Black Gates to maintain tension. And his female characters are memorable but marginal.

To counter the problem, Arwen is sent in from the sidelines as, Boyens admits, more of a ‘Hollywood stereotype’ at the heart of the action. She arrives to fight at Helm’s Deep and joins the Rohirrim’s charge on the Pelennor Fields. Purists might wince, but this isn’t as entirely unsuccessful as the filmmakers later claimed — on page she hacks at the Orcs with gusto and flashes of ironic humour. Whereas the romance with Aragorn is that bit too broad — the second film opens with Arwen and Aragorn frolicking naked in a pool in the Glittering Caves (which recollects John Boorman’s erotic leanings).

Ordesky, for whom Jackson’s vision was almost sacrosanct, admits to being uncertain of the tone of the scene revealed in the animatic on the pitch video. ‘My life is with you,’ Arwen gushes, having danced over stepping stones to surprise her beloved, ‘or I have no life!’

‘I never had any doubt, but that is the only place where I thought, “Huh, that is probably not what it is ultimately going to be”.’

With no Lothlórien, Galadriel’s moment is threaded into Rivendell as a dream sequence. As Frodo gazes into her mirror (to still see a burning Shire) the scene descends to an almost David Lynchian intensity of dreams within dreams.

Written between 1997 and 1998, the two Miramax scripts entitled ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ and ‘The War of the Ring’ (the name Tolkien had preferred for The Return of the King) would, as Marty Katz once claimed, still have made for exciting if shallower films. Here is the urgency of a Hollywood thriller — and the bluntness of Hollywood logic. Motivation is spelled out explicitly: ‘Those who resist Sauron are doomed …’ announces a scheming Saruman, ‘but for those that aid him there will be rich rewards.’

The biggest challenge Tolkien presented was the absence of a physical villain. ‘If you were doing an original screenplay, having your chief bad guy as a big eyeball would be a no-no,’ laughs Jackson. ‘You also wouldn’t have Saruman never leave his tower.’

His and Walsh’s first answer to the problem was to stir up some monster-movie action: poor Barliman Butterbur is skewered by a Ringwraith, and Sauron’s agents provide a constant airborne terror, attacking Gandalf on the battlements of Helm’s Deep where Gimli cleaves one with a battle axe. Sauron returns from the prologue in his super-sized, humanoid manifestation to duel with Aragorn: ‘… he stands at least 14 FEET TALL … is CLAD in sinister BLACK ARMOUR!’. A concept that would persist long enough to be filmed.

Ultimately, says Jackson, the issue of villainy would be addressed by making the Ring a character. ‘It speaks, it sings, and fills the frame — we were deliberately trying to give it presence.’

Evil is already in their midst, preying on weaker minds.

The two-film version cuts corners and concertinas events. Not illogically, Théoden mismanages his kingdom straight from Helm’s Deep, while Gandalf scours Middle-earth on the back of a giant eagle, Aragorn takes the Paths of Dead as a short cut, and to keep the clock ticking Arwen, mortally wounded by the Witch King, will perish if Sauron is not defeated.

Some details have already been filleted out of the treatment: Glorfindel rescuing Frodo on the flight to the ford; Sam looking into Galadriel’s mirror; Saruman’s dying redemption; the arrival of Elrond’s sons, Elladin and Elrohir; and the Ringwraiths trying to intercept Frodo at the Cracks of Doom.

There is, however, still a conscious attempt to keep tabs with the book: there is a Farmer Maggot, a Fatty Bolger, Bilbo attending the Council of Elrond and characters as obscure as Prince Imrahil and Forlong the Fat make cameo appearances.

Aside from a feisty Arwen, Gandalf is more frail and emotional, less in control; Gimli swears like a stevedore; and Faramir is described as a ‘fresh-faced seventeen-year-old’, making sense of why Orlando Bloom first auditioned for that part.

Ordesky wonders if he might be the only person at New Line to ever have read the original 280-page two-film script. He admired the coherent grasp of the material and the lovely, piquant details that would remain to elevate the films three years hence: a blazing Denethor casting himself off the rocky prow above Minas Tirith like a falling star; Sam’s impassioned speech on the slopes of Mount Doom, ‘I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you …’ Ordesky also knew that three films could offer so much more.

*

The Three-film Version (with New Line): ‘I will go to my grave saying that the crafting of those three screenplays was one of the most underappreciated screenwriting efforts ever undertaken,’ declares Ken Kamins proudly. ‘You are writing what is essentially a single ten-hour script, which you have to divide into three movies. You have to set up things in movie one that may not play out till movie three. And you’re burdened with having to explain the world to the neophyte.’

As soon as New Line came on board, they became impatient for Jackson, Walsh and Boyens to turn the two scripts into workable drafts of three. Jackson says this meant starting again with a page-one rewrite (essentially beginning afresh), but it is closer to what Boyens describes as a serious ‘rethinking’. Each draft would still be codenamed Jamboree, still ‘an affectionate coming-of-age drama set in the New Zealand Boy Scout Movement’. Only now it wasn’t simply the work of Fredericka Wharburton and Percy J. Judkins, but also Faye Crutchley (Philippa Boyens) and, for his contribution, Kennedy Landenburger (Stephen Sinclair).

Whole passages of dialogue and the structure and rhythm of specific scenes would be retained from the two-film draft, but restructuring to three films brought about a re-evaluation of what these films could be. Renewed emphasis was placed on what was emotionally satisfying. Posing the fundamental question: what were they fighting for? Action scenes needed to be earned on an emotional level. Characters needed to make sense. Legolas may be as nimble as Fred Astaire as he releases unerring arrows at blighted Orcs but this wasn’t a superhero film.

‘The script I’m most proud of is The Two Towers, because it was so frickin’ hard,’ says Boyens. ‘It was like, how do you break the story into three and then follow these different threads? And make people care. Also you’ve got no end — how do you create an end?’

Points of transition became a real issue with New Line. Concluding the first film especially would be a real bone of contention during post-production. Shaye was a huge fan of the books, but he was also a canny businessman in search of profit. He understood the screenplays would have to be representative of Tolkien’s work as a trilogy, but insisted that they also had to work as individual films.

If you missed the first movie, The Two Towers had to be a compelling piece of cinema. And if you missed the first two and still decided to see The Return of the King, it would have to work all by itself. Once The Fellowship of the Ring was a big hit, the editing of the ‘sequels’ re-orientated back toward a single saga.

Expanding into three films, says Boyens, allowed them the luxury ‘to try and do scenes to the fullest of their capacity.’ Within the exigent drive of plot they could explore character and build mood, even stillness. The priceless moment of Bilbo and Gandalf, two very old friends, contentedly blowing smoke rings and galleons upon the doorstep of Bag End; the camera gazing in awe upon the pillared immensity of Dwarrowdelf as Howard Shore’s score swells up through the ancient columns. Such poise was totally contrary to the hyper-kinetic dogma of millennial blockbustermaking.

Obviously they also had room for plenty more Tolkien, and some painful excisions were immediately remedied. ‘It was such a relief to have Lothlórien back,’ says Boyens, and the Elven forest was the first thing she returned to its designated place.

The book was full of renewed possibility.

Says Jackson, ‘Unlike most movies where the pressure comes and you literally take twenty pages out, our scripts actually grew by thirty to forty pages, because we would keep finding stuff in the books. We were constantly thinking, “God, we really should be filming this, this is great, and we’d then write a page, show it to the actors, and they’d go “this is good” and I’d say, “You know, on Friday, I think we can squeeze this new scene in pretty simply.” It was very organic.’

The problem was it never ended. They couldn’t stop writing, editing, re-writing, trimming, extending, delving into the mines of the text, working with the actors, twisting and turning the mythology into cinema. This went on literally in tandem with the shoot. A honing of story in the same way a special effect can be bettered with care and attention. Such that there was never a definitive finished screenplay, not on page.

An early draft of the three-film version, dated 20 November 1998, reads like an alternative universe to an alternative universe, with many of these scenes shot and abandoned. Opening with Frodo and Sam surveying the limits of the Shire from a hilltop, Farmer Maggot clings on and the hobbit heroes encounter the first Ringwraith without Merry and Pippin. Rivendell, as we shall see, awaits a major overhaul. There is an Orc assault on the borders of Lothlórien, where Aragorn has a flashback to the days he spent there with Arwen and Frodo glimpses Gandalf in Galadriel’s mirror.

In this version, the second and third films radically depart from the book, with Arwen’s participation expanded even from the two-film draft. She follows the Fellowship to Lothlórien and then on to Edoras rescuing the refugee children from an Orc attack along the way. The love triangle is revived from the treatment, with a semi-comic rivalry established between Arwen and Éowyn. Arwen still battles at Helm’s Deep, still skinny-dips with Aragorn, still helps fight off a Ringwraith that swoops for Pippin, and still rides with the Rohirrim, but now alongside Éowyn disguised as a man (diluting the whole effect). Arwen will be left for dead by the Witch-king before Éowyn dispatches him. And Sauron still confronts Aragorn at the Black Gates.

They were constantly trying to insert the structural lessons gleaned from McKee to the glacial magnificence of Tolkien: climaxes, twists, foreshadowings, turning points and delayed reveals. Balanced with wilfully obscure references to his deep mythology. His archaic language could have enormous power when delivered by an Ian McKellen or Christopher Lee. But for clarity they would trim and edit from the book, moving passages around in the chronology or between speakers like a slider puzzle.

Boyens’ ancient prologue was still being reworked in post.

‘I first wrote it as Gandalf narrating,’ she says, running back through the manifold revisions in her head — there had been a Frodo-narrated version at one stage. ‘And then I wrote it in the voice of Galadriel. That was Fran’s idea, and it was a good one. Then when we were recording the ADR in London, I said to Fran, “Can we overlay it in Elvish?” You want that sense of strangeness of history.’

The trilogy’s overture carries the quality of a dream as Blanchett’s yearning voice pulls us across the frontier into Tolkien’s imagination.

*

The creative dynamic that evolved between Jackson, Walsh and Boyens would define the trilogy: the visualist devising heart-stopping scenes; the realist seeking emotional truths; and the Tolkien authority mindful of the Elvish provenance of Gandalf’s sword. As an unwritten rule, Jackson was responsible for what they categorized as the ‘Big Print’ set-piece stuff such as the battle with the Cave-troll (which elaborates on Tolkien to great effect). Something, Boyens soon noticed, he did with an extraordinary immediacy and originality. As if in response to that strangeness in Tolkien’s world no sequence was allowed to bear the formulaic imprint of a Hollywood blockbuster. Jackson, writing in those caps in which you can feel the camera’s hungry eye: ‘The dark WATER BOILS as the HIDEOUS BEAST lashes out at the FELLOWSHIP!’

‘Philippa and I were very invested in the emotional content of the story,’ Walsh explained in a rare interview. ‘It’s easy for those things to be obscured by spectacle and the sheer sort of exhaustion of that final ascent to Mount Doom. But we wanted to touch the audience in a meaningful way. Maybe that’s an easier thing for us to do because we are women.’

Boyens did the bulk of the physical typing sitting up in bed with her laptop or at her desk. ‘We got into this rhythm. I was the faster typist and better speller. Fran’s great because she can see the scene in her head. When I write, the words don’t come unless I actually physically type them.’

They were known to spend a whole day in their pyjamas, writing, writing, writing. ‘Then Fran would have time with the kids,’ recalls Boyens. Jackson and Walsh’s children, Billy and Katie, were still only infants. ‘So it was nuts,’ she laughs. But nothing could beat that moment of breakthrough. When, as Boyens puts it, ‘the landscape held’.

Walsh was the driving force. Jackson’s partner would be the first to admit she wouldn’t naturally have chosen to adapt The Lord of the Rings. She had been seduced by Jackson’s passion for the possibility of something epic. As much as she was caught in the slipstreams off the Misty Mountains, addicted to Middle-earth, she could remain more academic about the material: how does it work as entertainment?

‘I learned how to write from her and from Pete, but mostly from Fran,’ says Boyens. ‘There’s so many holes and missteps with a film. There are so many different ways you can go and so many things that you have to break. I’m someone who would paper over the cracks. She couldn’t. The other thing that I learned from her is that it’s the ideas which are informing the story that are important. Why would anyone care? And understanding how you take what is interior, especially for a character such as Frodo, and translate it to film. She was masterful at the Gollum-Sméagol dynamic.’

Kamins can see that they were a unique producing-directing-writing unit. ‘You understood that they were close. They were willing to argue with each other to make something better. To push each other to prove why their point was right.’

And the clear distinction of roles could be deceptive. Walsh and Boyens could be good on the Big Print action scenes and Jackson excellent on the fine print of Tolkien.

Still, freed up by the obsessive dedication of his co-writers, Jackson utilized his energies across preproduction, finding the visual texture with which to clothe the bones of the words. As shooting bore down on him like a mûmak, the director took more of an ‘overarching eye’, says Boyens. Generally, after a team discussion, she and Walsh would do a draft of a scene and then Jackson would do his pass.

‘I was literally almost doing a shot list,’ recalls Jackson. ‘A lot of screenwriters say don’t tell the director what to do, but I guess as I’m the director I don’t mind. It helps when I am sitting there reading the script a year later and knowing that I had a thought to do a close-up.’

The original three 150-page scripts presented to each actor were always available for consultation, but they were only blueprints. Rhys-Davies laughed about the dreaded brown envelope that would be slipped under their door each morning with that day’s revisions.

Sean Astin describes the scripts as ‘fluid’. But if an actor wanted to adjust a line on set, try it in a different way, they would be met with resistance. Jackson would joke that he dare not cross the ‘script Nazis’. Given what Boyens and Walsh were going through, he may have been genuinely fearful. They were constructing a monumental house of cards where one minor adjustment could bring the whole edifice crashing down.

Yet the cast did contribute. Both in preproduction and production they would meet with Walsh and Boyens to talk through upcoming scenes. Viggo Mortensen, who always had the books about his person, was relentless when it came to his character. Astin likes to think of it as keeping the filmmakers’ ‘feet to the fire’. And that drive brought Aragorn to life.

Astin remembers coming up with the idea that Sam had been secretly spying on the Council of Elrond throughout. How else would he be aware of what had been decided? ‘Sam belonged there,’ he had argued to a sceptical Walsh. It was, he insists, ‘a legitimate desire to act as an audience surrogate’.

A compromise was reached where Sam is seen hiding in the shrubbery. Astin wasn’t wholly mollified, but nothing was as emblematic of the brinkmanship of writing — and indeed shooting — as mounting the Council of Elrond. ‘Just don’t make me go back to Rivendell,’ Boyens would remonstrate whenever things got complicated.

A great gulp of exposition that often defeats casual readers of the book, here we are introduced to the members of the Fellowship and get a lesson in the complexities of the ‘big picture’ via a succession of stories within the story, told at exorbitant length by individual characters. Moreover, Jackson has an allergy to any form of reportage. Show-don’t-tell is the heartbeat of cinema. You have to picture things, not have actors describe them — even actors as persuasive as McKellen. But this would necessitate a frenzy of flashbacks.

In the book, the Council is where Gandalf finally tells the tale of his capture by Saruman. As early as the two-film draft the writers had decided cleverly to cut away from the hobbits’ journey through the Shire to portray Gandalf’s excursion to Isengard in real time. This both exploited the potential of two ancient wizards duelling with shockwaves of magic and teased the possibility that the Bombadil episode could have occurred in the meantime. ‘We chose to leave some things untold, rather than left out,’ is Boyens’ escape clause. Only Gandalf’s eagle-spirited getaway is suspensefully withheld until Rivendell.

To avoid the scourge of reportage the script syncopates a variety of flashbacks and reveries throughout the story without stalling momentum. A feat doubly impressive given Tolkien’s epic mode didn’t provide much inner life for his characters — Gollum expresses his internal narrative aloud.

‘Backstory was incredibly difficult to do,’ confesses Boyens. It had to be character driven, or action driven. Nevertheless, as written, the Council scenes were yawning to a stifling forty minutes while everyone sat in a circle talking politics. There was no way they could effectively put the story on hold for so long. Figuring out the scale issues and eyelines alone was headache inducing.

Ordesky remembers joining Walsh and Boyens at the shoot’s hotel HQ while on location in Queenstown as the dreaded Council loomed in the next block of filming. They were in one of the most beautiful places in New Zealand unable to leave the hotel as they wrestled the scene into submission. ‘It was such an education,’ he says, ‘seeing their process of laying tracks in front of the moving train, as Fran liked to say.’

Says Boyens, ‘One of the things that I learned in particular and, I think, Fran and Pete did too — and actually the studio did too — is that you didn’t have to explain the history of Dwarves. You just needed John Rhys-Davies to turn up and be a Dwarf.’

They needed to trust the actors.

As Boromir, Sean Bean immortalizes the finished scene with his portentous, half-whispered line reading: ‘One does not simply walk into Mordor …’ A passage of dialogue scribbled on a piece of paper and literally balanced on his knee (you can spot him subtly glancing down).

‘He was so good,’ says Boyens, savouring the victory. ‘That tension between him and Viggo … Man, it was great casting: those two opposite each other … And I’m very proud of my Pippin line: “Where are we going?” You kind of needed it.’

The humour in the scripts often goes uncelebrated. Enriched by the fine cast, the comic elements help puncture any drift toward pomposity. Merry and Pippin’s chittering banter, Gandalf’s crabby exasperation, Gimli (surely Jackson’s avatar in the films) and his rivalry with Legolas, Sam and Gollum, the slowpoke Ents and the quarrelsome Orcs all contribute a flavour that is consciously Jacksonesque.

‘It’s taking the piss,’ says a delighted Boyens. ‘And that is Pete’s sense of humour definitely. He always says that you don’t earn the pathos if you don’t make people laugh.’

Away from the wellspring of Harryhausen and Kong, Jackson adored the sublimely engineered slapstick and anguish of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and the gonzo follies of Monty Python. Comedic forces welcome amid the serious business of saving the world.

*

In early 1997, Michael Palin was in Wellington for a one-man show, and Jackson wasn’t about to pass up the opportunity to go backstage and meet a hero. They shared the usual pleasantries. Jackson telling the erstwhile Python how much he appreciated his work. Palin enquiring after what the director was currently working on. They got talking about The Lord of the Rings. Then it occurred to Jackson to ask a pertinent question.

‘Do you know where Alan Lee lives?’

Jackson was desperately trying to get hold of the seemingly reclusive artist’s expertise, but so far in vain. It had occurred to him that Palin had worked with Lee on an illustrated children’s book called The Mirrorstone — he may have even got hold of a copy — about a boy travelling to a wizardly realm via his bathroom mirror.

‘Ah, he’s a funny chap, isn’t he?’ Palin recalled. ‘I’ll find out for you.’

A few weeks later an email arrived bearing Lee’s Devon address. ‘It’s true,’ laughs Jackson. ‘Michael Palin came to the rescue. No one could figure out how to contact him.’

While re-reading The Lord of the Rings, Jackson found himself eagerly anticipating the next of Lee’s wonderful illustrations. He was struck by how utterly removed the pictures were from that juvenile vogue for muscle-bound Conan-clones draped in a buxom wench that adorned heavy metal albums and Dungeons & Dragons boxes. ‘They were sort of pastoral, with these elegant pastels. Sort of historical, I suppose,’ he says. ‘We fell in love with those pictures.’

As he surveyed Middle-earth with his internal camera it was Lee’s version of the world he would likely see. So he began to gather together as many of the artist’s calendars, book covers, posters and compendiums of Tolkien artwork as he could lay his hands on. This was pre-internet, pre-eBay, so it was a matter of trawling second-hand bookshops, collectors’ fairs, jumble sales and nagging friends to scour their attics.

‘I was tracking down calendars going back to the seventies, trying to see who the other artists were. That was how we saw John Howe’s work — in calendars.’ Howe had contrasting strengths. Lee was good at the gentle whimsical, hobbit stuff — it was very beautiful. The more dynamic Howe, in Jackson’s opinion, ‘did really great Nazgûl’. His paintings were ‘like freeze frames of a movie’.

Jackson wallpapered an entire room with the two visions of Middle-earth, hoping to absorb the poetry and drama of the images. Then it occurred to him that osmosis was unnecessary. Why not put your inspirations on the payroll? And the decision to involve Lee and Howe as guiding lights was another piece of applied Kiwi logic that bled into the visionary. In a stroke, the films became a continuum of what for many was the definitive Tolkien aesthetic.

However, despite the best efforts of Miramax, Lee had proved elusive. All they could ascertain was that he lived in the middle of Dartmoor — the insinuation being he was some kind of mad hermit. They were also rather suspicious he was a minion of the Tolkien Estate.

Fusing Bruegel with Arthur Rackham, Lee is arguably the greatest of the Tolkien school. Howe is exalted too, and the likes of Pauline Baynes, Ted Nasmith, Ian Miller and Michael Foreman. But Lee, certainly in recent years, is largely responsible for shaping our perception of what Middle-earth looks like.

‘I get that, I get people saying my work is exactly as they imagined it,’ he says. ‘But it’s interesting because often it is not exactly as I imagined it when I read the book. But that is the way it turned out through the process of drawing. I would say it is in the right ballpark.’

In conversation Lee speaks in hushed, careful tones as if you’ve surprised him in a library. Silver-haired and bearded with an intense, indecipherable gaze, he is well cast in a silent cameo as one of the nine kings (second from the right) in the prologue. The immediate impression is someone both reassuringly adult and somewhat mysterious.

Lee had moved into illustrating paperbacks from art school in the late 1960s, gravitating toward anything ‘slightly weird or ancient’. He was responsible for the first fourteen covers of that young reader’s rite-of-passage The Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories. Through renowned publisher Ian Ballantine3 he contributed pictures to two best-selling anthologies: Faeries and Castles. Lee had first read The Lord of the Rings when he was seventeen and working in a graveyard, but it wasn’t until Castles he first attempted Tolkien with versions of Barad-dûr, Cirith Ungol, and Minas Tirith. These drew the approval of the Tolkien Estate who agreed to his being commissioned to paint fifty watercolours for the 1992 centenary edition of The Lord of the Rings. In 1996, he was asked to illustrate The Hobbit.

Like a portent, in 1997 a producer from Granada television approached him about providing concept art for a proposed twelve-part television adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. ‘The script actually read quite well,’ he remembers. ‘But in the end he couldn’t get the approval for it.’

Then one morning a package arrived by courier all the way from New Zealand containing two videos, two scripts, and a letter of introduction from a fellow named Peter Jackson. He helpfully included a number to call. The videos were Heavenly Creatures and Forgotten Silver. ‘He had neglected to put in Bad Taste,’ notes Lee. He watched the brilliant Heavenly Creatures first. Then he read the letter, in which Jackson explained that the scripts were for another potential adaptation of The Lord of the Rings and would Lee like to be involved?

Jackson, meanwhile, had been following the package via his courier and knew it had been delivered, satisfying himself that he wouldn’t hear back for weeks. Hours later his fateful phone rang. It was Lee’s quiet, gracious tones announcing that he would love to be involved. As luck would have it, he was finishing up a project. With no pressing family ties, he was ‘kind of free’.

The artist laughs at the memory. ‘I went down to New Zealand for six months. I ended up staying for six years.’

Howe had heard the odd rumour about a potential adaptation of the book, but knew little else. Born in Vancouver, Canada, he had since settled among the chocolate box lakes and mountains of Neuchâtel in Switzerland, no less removed from Hollywood than deepest Devon. Growing up in a rural outpost he had known ‘ever since he could remember’ that he wanted to live off his artistic talents, but never dreamed it was possible. He should finish high school — get himself a normal job.

His life changed when Tolkien-themed calendars started appearing in the town bookstore in the mid-1970s. It wasn’t that he was an avid fan. He read The Lord of the Rings during high school, having visited The Hobbit as a child. ‘They didn’t really strike me as anything,’ he admits, enjoying the irony. An opinion that might have been shaped by the fact he read the trilogy in the wrong order. Someone had always beaten him to The Fellowship of the Ring in the local library. So he ended up reading The Two Towers and Return of the King before the first part. ‘I was a bit confused,’ he laughs.

The calendars showed that it was possible to have a career painting pictures based on fantasy novels. Suddenly Middle-earth came alive as a world of infinite possibility; he still remembers his first attempt: ‘It was from the Pelennor Fields and had a Frank Frazetta-like touch — a reptilian creature and Nazgûl rising up to tackle Éowyn.’ Howe would pick up the latest calendar and each month do his version of the picture.

Over the years, as he established himself as an illustrator, Howe diligently sent samples into HarperCollins for their Tolkien calendars. Until, in 1987, he finally had three pieces published.

Rather than a package, Howe received a phone call in the middle of the night. Jackson had tracked down the artist’s number with relative ease but in his excitement had forgotten about the time differences. Ten days later Howe was on a plane to New Zealand.

‘The commitment was extremely light at that stage. The project had yet to be confirmed, and if things didn’t work out, you have your ticket home.’ While his wife and son would follow him, Howe never relocated with any permanence to Wellington. Conscious of his son’s education he would exit the project when production finally got underway in 1999. ‘We were back home once sets were being built.’

Howe shares the same meditative delivery of his colleague but is more eccentric. Where Lee is almost serenely composed, Howe has an undercurrent of energy that can’t be stilled. With his thin frame, flowing brown hair and beard he cultivates a little wizardliness, that or a mad professor. He too is one of the nine kings (second from the left), but harder to recognize beneath his wig and frown.

Jackson laughs. ‘We did Alan first and then we did John. Then we figured out that they had never met each other, and I thought, “God, I hope there’s no rivalry here.” They literally met each other on the aeroplane.’

They knew of one another’s work, of course, and had vaguely corresponded. But it was on the middle leg of their journey from Singapore into New Zealand in 1997 that they became acquainted. Howe had been sitting downstairs when one of the stewards approached him.

‘A Mister Lee wants to meet you.’

‘I didn’t even make the connection,’ he says. So it was midway over the Indian Ocean the two artists were introduced, and found they got on very well. Which was a relief.

Although, while changing planes at Auckland, Lee — and the airport ground staff — was startled to discover Howe had packed a suit of armour. As a serious medieval re-enactor he was keen to bestow his historical expertise in forging suits of amour on Weta Workshop, sceptical they were up to the task.

Howe still has a ‘laser-sharp image’ of arriving into Wellington for the first time, following the coastline as it snaked along the southern hem of the North Island. ‘It was an extraordinary feeling.’

From the airport they were driven straight to Jackson’s house at Karaka Bay and over the kitchen table, adrenaline keeping overwound body clocks ticking, began to understand how the director saw them working with the production. They would, Jackson informed them, design everything, with the division of labour laid out as per his appreciation of their respective gifts: Lee the light side, Howe the dark. Naturally, lines were blurred. Howe would design the vestibule of Bag End and Lee created Orthanc. Still, it was a place to start and this way they could cover more ground.

‘It was also pretty clear Pete wanted to get going on the bigger environments,’ notes Lee, who spent his first two weeks in Helm’s Deep.

For Howe it was all entirely new, Lee at least had some experience creating concept art for another Python, Terry Jones’ Erik the Viking, and Ridley Scott’s Legend. There was only one strict instruction: don’t curb your instincts in any way for a film. ‘They told us quite quickly that if you can draw it we can make it,’ says Howe.

Everything from Minas Tirith to door hinges fell into their remit. There would be no hand-me-downs from old epics. Stationed amid the inspiring bustle of the Workshop, they were going to design this ancient world inch by inch. Recalls Howe, ‘We weren’t working on computers at that time. That sort of kicked in later. All you needed was enough good paper and enough pencils.’

On a workaday level nearly all of their design work was pencil, colour was too time consuming and too prescribed. They soon understood they were cogs in a giant mechanism that would have to churn out Middle-earth on an industrial scale.

Says Jackson, ‘Usually in design meetings you’d been talking about some location: “Maybe there is a bridge here and a building here.” Then everyone would go off and come up with stuff. But Alan or John would have their pads and as I was talking they would sketch up something. By the time I had finished describing it they could show me a sketch. It was like instantaneous design.’

‘Peter’s also somebody who likes looking at artwork,’ appreciates Howe. ‘He enjoys artwork. He’s art literate in that sense.’

The one exception to the no-colour rule was when Howe, whose work would be more legibly dynamic to a studio, was asked to paint a dozen ‘great moments’ for the pitch meetings in Los Angeles. Lee added large pencil drawings and sketchbook material. They mounted them into a slideshow using Photoshop, something they were only beginning to figure out. ‘It was all a bit naff really at that stage,’ admits Lee.

It was a strange time. As Miramax wound things up in Wellington, Lee and Howe simply went home. That was that. But they had barely had time to unpack their HBs and plate armour when news came that the presentation had worked, a deal had provisionally been struck with New Line and the artists were back on a plane to New Zealand. ‘Peter’s no slouch,’ notes Howe, approvingly. ‘He’s a clever man and managed to pull it out of the fire.’

*

Why, when, where and with whose money Jackson was going to direct the films was decided. The question now confronting him was how was he, personally, going to direct so much story? What would his Lord of the Rings look and feel like? What would it sound like? What style would he bring to Middle-earth?

While Heavenly Creatures and The Frighteners had shown there was more to the director’s repertoire than splatter satires, The Lord of the Rings was a leap of faith. Would he have to curtail his natural excesses to be epic? Was there a nascent Cecil B. DeMille or John Ford or David Lean beneath the crash zooms and wacky angles?

Perhaps the better question to ask is what was there in the flare and versatility of Jackson that so befitted The Lord of the Rings? As the pitch documentary proclaimed, he couldn’t have been more thorough in his development of the films. The labour of screenwriting was providing him a narrative roadmap — quite literally in terms of location — as well as inspiring camera moves. But Jackson’s instincts split between groundwork and natural daring. He was a thrilling stylist who had seen as many slasher movies as Lawrence of Arabias. He was a technically brilliant storyteller guided by an inner Einstein with no space or time for formulaic thinking.

Nevertheless, his governing principle possessed a Kiwi-like directness: ‘I was trying to make it feel real. It wasn’t so much thinking about what can I do differently, rather than what can I do for the story? We really approached it like it was real; this is authentic, it is not fantasy, it is a piece of the past.’

Jackson is the artist who once cooked special effects in his mum’s oven. Who made ‘realistic’ alien vomit out of yogurt, pea green food colouring and baked beans. When he found the consistency too runny he added handfuls of soil before his Bad Taste actors dug in. Back in those early days he even made puke by hand. He loves the tactile — the texture of the world. Braindead is an orgy of sensation. The sheer blood-drenched chaos pours off the screen until you feel sticky just watching it. Inches out of shot you sense the gleeful filmmaker caked in his own stage blood laughing till his lungs burst. When he watched Harryhausen it was as if he could reach out and touch those strange creatures.

‘That’s what I loved about Pete’s approach,’ says Boyens, ‘and made me feel this was the right person. This guy who did Braindead and Meet the Feebles — no matter what he did he wanted it to feel real and earthy, and there’s a lot of earthiness in Tolkien’s work.’

It was Lee and Howe who revealed the dizzying scale of Middle-earth, and warned him not to giggle.

‘Everything was always bigger than I thought, and better,’ he says. The artists, rooted in Tolkien’s grandeur, would always go way beyond what was in his head. Design meetings became thrilling symposiums where the world expanded before his eyes. Not to be outdone, he soon started pushing them for even bigger and better.

He had become fascinated by Lee’s cover painting of a flooded Orthanc on his well-thumbed copy of The Two Towers: the black, angular walls ascended out of frame, carved with vertical crenulations like the scratches of a blade and wreathed in moody smoke. But the picture only covered the lower four stories. Like many readers, Jackson longed to know what the top of the tower looked like. Only he got to ask. ‘I was able to show Alan the picture, which I had lived with for years, and say, “Just create the rest of the tower.”’

Lee unveiled an awe-inspiring Gothic skyscraper whose riven sides tapered to a flat summit with blades jutting from each corner like the peaks of an iron crown. Orthanc was fixed in our minds for ever more.

This search for the real in the unreal was a universal obsession. No individual in the swelling ranks of the production was prepared to let their corner of Middle-earth go by unverified by a form of collective integrity. Lee would go through a sequence of sketches that gradually ‘crystallized’ into the ideal image by ‘natural selection’. In other words, he would keep drawing until it made sense, imagining himself inside the picture examining every possible angle for the scene to come.

‘Each image was a virtual place that had to be completely consistent.’

They could exaggerate, but Lee and Howe would know intuitively if the credibility of the story was threatened. ‘You wanted people to suspend disbelief for the time that they’re there,’ says Howe — there were points you could assume magic was at work. ‘In the case of Barad-dûr, you can’t build stone that high. It falls down. So I assumed Sauron has put some dark power into the foundations.’

Indeed, when Sauron is destroyed with the Ring, the tower disintegrates like pie-crust.

The two artists would design every facet of a building inside and out far beyond the bounds of what we see on screen, satisfying their own insistent logic. Imagining Orthanc’s summit, Lee provided the outline of a doorway in one of the fins to explain how Saruman gained access to the roof. ‘There are stairways leading all the way up,’ he maintains. ‘You don’t see it because it is so dark.’

Like the writing and the designing of the film, how it would be made on the levels of lighting and planning shots, practical and computer-generated effects, editing, music and sound design, would be answered by varying degrees of near scientific research and making it up as they went along. The belief they would find a way to work wonders. But it was a practical magic.

Jackson was to an extent letting Middle-earth guide him. Storyboarding and pre-visualization had the same aura of experimentation. As the scripts were being written — and rewritten — he and a young protégé named Christian Rivers began to storyboard the film. The affable, multitalented Rivers had become a permanent fixture in Jackson’s inner circle after his fan letter led to an invitation to lend a hand on Braindead (Rivers insists that he called). A gifted artist, he has storyboarded every Jackson film since, as well as branching out in both divisions of Weta (he was a digital artist on the Contact effects sequence).

In layman’s terms, ‘pre-viz’ denotes the mapping out of camera moves ahead of time on a computer, usually concentrated on the more complicated sequences. Today, pre-viz is done within virtual environments — as it would be on The Hobbit films — but in 1999 the only sequence planned with animated pre-viz was the fight with the Cave-troll (they would later digitally pre-viz the mûmakil attack for The Return of the King). Otherwise, their unofficial, analogue variation of pre-viz amounted to Jackson crouched over Weta’s growing portfolio of miniatures holding a tiny ‘lipstick’ camera.

‘You always have a perception of what it could be in your head when you write a script. But it gives you a chance to play around with it. I am always looking for other angles. It gives you an ability to actually explore and experiment.’

With the thirty-foot miniature of Helm’s Deep, complete with the Hornburg keep, Deeping Wall and polystyrene cliffsides recently constructed with Lee’s assistance, Jackson went out and bought 5,000 1/32nd scale plastic soldiers. ‘Sort of Medieval guys with pikes,’ he reports happily, having cleaned out Wellington’s toyshops. A poor soul spent two weeks laboriously gluing them down in groups of twelve to blocks of wood so the director could move formations of Uruk-hai around like Napoleon.

*

Meanwhile back in Hollywood, following the fateful meeting with Bob Shaye, lawyers’ phones began to sing. Three separate deals had to be struck: one with Miramax, a new one with Saul Zaentz and one with Peter Jackson. Most pressingly, Miramax were due to be reimbursed their development costs. Kamins had been clear about Harvey’s terms when setting up the meeting. He wasn’t going to be accused of ‘buffaloing’ anyone; getting everyone excited then springing the exorbitant catch on them, which included executive producer credits for the Weinsteins. Shaye admitted the terms of the deal had almost dissuaded him from the meeting, but forty-eight hours afterwards he was on the phone to Harvey.

Says Kamins, ‘Harvey must have dropped the receiver, I don’t think he believed for five minutes this would happen.’

He came around quickly enough. Scenting he could both reclaim his investment and land five percent of the gross with no further risk on his part, he switched back into street-dealer mode. And saw the wisdom in allowing an extension to his initial four-week stipulation for a signature.

Room to breathe.

The reality of New Line’s commitment to the project becomes stark when you consider that, according to Ordesky, they spent in ‘the low twenty millions for the rights’ not only to pay back the Weinsteins but to fund Jackson, Walsh and Boyens to redo the scripts and begin preproduction. This was to even get to a place where they could say yes to backing three films.

The first in the trilogy of deals was the trickiest. The production had to be extracted from Miramax and then employed by New Line, who first needed to instigate a process of vetting Jackson’s filmmaking outpost. Thankfully, the vibrant and intelligent Carla Fry, head of physical production at New Line, arrived to tour the facilities, get a sense of his capability and to come up with a credible budget.

Ordesky’s double-edged reward for bringing Jackson and his ambition through the door was for Shaye to position him as executive producer on the project. After all he knew the book and the director. ‘Bob and Michael both believed in the pride of authorship, that if you were an advocate of something then you’d work harder and smarter for it because you were invested in it. So I was surprised and pleased when Bob said, ‘Listen, you’re going to work on this. You’re the Tolkien fanatic, you’re the Peter Jackson advocate, you can be there to steer us through this process.’

What Ordesky didn’t yet know was how often he would play messenger, mediator and meddler between an irresistible force and an immovable object. He would have to play Gríma Wormtongue one day, Gandalf the Grey the next.

As sums were done and fine print parsed, Jackson and both divisions of Weta were plunged back into a familiar period of uncertainty. The cheques from Miramax had ceased, and New Line had yet to conclude a deal. Knowing it could easily fall apart again — you could smother LA County with the paperwork from collapsed movie deals — Miramax had their own team of bean counters in Wellington totting up everything from artwork to Orc prosthetics, which they considered bought and paid for — something Jackson disputed.

Taylor is haunted to this day by the memory of Miramax suits, scurrying around like Goblins, discussing how to best package up their assets to be shipped back to America. If a miniature didn’t fit the shipping crate — as was the case with Helm’s Deep — they concluded it should be chain-sawed up into portions that would fit. ‘I felt sick,’ he admits.

Lee had surreptitiously been taking photographs of all his pictures in case they disappeared.

By contrast, Fry — who passed away from cancer in April 2002 having only seen a completed Fellowship of the Ring — like Marty Katz, became a great advocate of the films. ‘Carla was a real unsung hero of the whole process,’ says Ordesky. Jackson had been pushing for $180 million to make two films, and Fry would stand up for the fact that three films could be made for $207 million.

It was a bold assertion. There were still so many uncertainties. No studio had ever made three films simultaneously. There was no precedent to fall back on, no one to ask how it could be done. As Ordesky explains, a number of what they call ‘critical assumptions’ went out the window. ‘Assumptions about transportation, about lodging, about all kinds of things involved in making films, because no one had ever shot anything on that scale in New Zealand.’

There had to be a hybridization of the Hollywood way with New Zealand culture. None of this was necessarily cynically driven, they were intent on enabling Jackson to make the films, and it was at this time the very capable Barrie Osborne was hired as producer.

Jackson had been keen for Katz to stay on. They had been in the trenches together and Jackson had come to depend on the wisdom beneath the Hollywood tan. More importantly, Katz had shown his ‘loyalty’ to the production. But he had family commitments. What would amount to five years away in New Zealand was too big an ask. So he never did get to roast his chocolate-coloured Porsche around the leafy avenues of Miramar.

Roughly four weeks after their first meeting with Shaye, $12 million was wired through to Miramax and The Lord of the Rings was officially the property of New Line Cinema.

In the interim, a deal was swiftly reached with Zaentz. This was now a simpler process both because it retained much the same legal framework as had been agreed with Miramax and the fact Shaye and Zaentz, in another impossible stroke of fortune, were old friends.

Zaentz later mentioned that Miramax had been facing a large payment to renew their option on the book, which was undoubtedly another motivating factor in Harvey’s willingness to cut a quick deal. The vocal impresario, who came to know Jackson and Walsh at various press events following the films’ release, would maintain that it was only because of ‘their intelligence and enthusiasm’ he ever parted with the rights. His view (in hindsight) on the Miramax situation was ardently pro-Jackson. The thought of a single film of the book was ‘absurdity’. When Shaye called him with the proposal of New Line replacing Miramax on the project, Zaentz had one stipulation: ‘Only with Peter Jackson.’

Ironically, New Line still had to close a deal with the director who had been desperately knocking on their door, which also meant closing a deal with Jackson’s fleet of production subsidiaries: Wingnut Films, Stone Street Studios, Weta Workshop, Weta Digital and his post-production facilities. Positive, businesslike relations tensed when New Line cottoned on to the fact they had been the only players in town. Shaye felt duped, and the pro-forma contract shaped by Jackson’s team would be subject to some compromise. Jackson lost his pay or play deal (which had meant he would be paid even if the films weren’t greenlit). He would effectively only be compensated upfront for one and a half films with backend bonuses. He and Shaye would have to reach an agreement on final cut.

On 24 August 1998, in lieu of any official announcement, the story was leaked to the Los Angeles Times. ‘New Line Gambles on Becoming Lord of the Rings’ ran the headline. Written by film reporter and genre geek Patrick Goldstein, it is curiously off the mark: setting the budget at a conservative $130 million, and claiming that Jackson hoped to have the first film ready for Christmas 2000 (he would still be shooting!) with the next two instalments slated for summer and winter of 2001.

It is a quoted Shaye who proves the most prescient. ‘Having seen Peter’s script and demonstration reel we believe he has the ideas and the technology to make this a quantum leap over the fantasy tales of ten or fifteen years ago.’

Goldstein also noted that on the internet fans were ‘already casting Sean Connery’ as Gandalf.

Between the lines, it was clear that sceptisim still reigned in Hollywood. This was commercial suicide.

Ordesky was actually sent a copy of Final Cut, that book about the catastrophic money-pit of Heaven’s Gate. ‘It was not given in a kindly way. I thought that if anything is going to throw me off my game it is that book; but this was not Heaven’s Gate.’

And Peter Jackson wasn’t Michael Cimino. He was an ambitious and often obsessive artist, true, but he was also a very practical, diligent, open-minded New Zealander. A quality displayed not least in his burgeoning relationship with fans. Then a similar kind of devotion ran in his veins.

In an extraordinarily smart move, the kind of gesture that comes naturally to Jackson, on 26 August 1998 (two days after the Los Angeles Times story) he agreed to take part in an online interview with the website Ain’t It Cool News. He would answer the twenty most pressing readers’ questions, addressing any concerns.

Says Kamins, Jackson wanted to communicate as early as possible that he was up to the task. ‘Ain’t It Cool News was a very vogue site at the time, and Peter’s hope was that he would show people that he understood the world and if people disagreed with decisions he was making at least they would disagree thinking, “Okay, this guy understands the universe”.’

The site’s mailbox was besieged with over 14,000 questions, not just from fanboys but fantasy authors and literature professors. Jackson ended up responding to forty questions covering the budget, special effects, how to create hobbits and mount battles, and how with the help of New Zealand’s glorious landscapes he was going take moviegoers into Middle-earth.

‘I do not intend to make a fantasy film or a fairy tale,’ he declared. ‘I will be telling a true story.’

‘Peter wasn’t a dreamer,’ affirms Ordesky, ‘he had pragmatic plans for how to make dreams come true.’