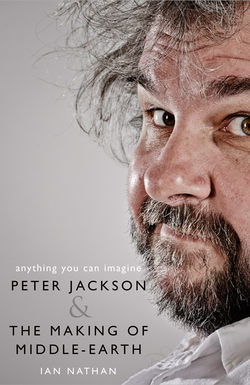

Читать книгу Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth - Ian Nathan - Страница 8

PROLOGUE Journey’s End

ОглавлениеMonday, 1 December, 2003 was a typical summer’s day in Wellington. The sun was doing its level best, but the eternal, maddening winds were already scuffling over the bay and muscling their way inshore to ruffle pennants and hairdos but never spirits. Not on this day.

The red carpet was less familiar but not unexpected. Over 500 feet of imitation velvet swerved up Courtenay Place to the doors of the Embassy Cinema, recently refurbished at a cost of $5 million to a fetching cream and caramel Art Deco scheme. One of the myriad cinematic gifts Peter Jackson had bestowed upon his hometown. Fittingly, fifteen years earlier, his debut film, Bad Taste, had premiered at the Embassy, albeit with less salubrious décor and a smaller turnout.

Less in keeping with the old movie-palace aesthetic was the cowled Nazgûl astride a fell beast that had landed on top of the cinema virtually overnight to take up silent watch over the day’s festivities.

That full-size model, or maquette, with its great-scooped neck and outspread wings, sculpted by the imperious talents of Weta Workshop, still exists. Like so many Middle-earthian relics, it has been squirrelled away for posterity in one of Jackson’s dusty warehouses, the Mines of Moria of the Upper Hutt Valley.

Jackson might have to still undertake the mandatory global press tour on behalf of his new film, with its procession of glad-handing and crowd waving, but he had been adamant that the official world premiere for The Return of the King was to be in Wellington, the city at the heart of the production. This was the victory lap for a filmmaking triumph that, even in his innermost fantasies, he could never have imagined, and he wanted to share the moment with the people who had contributed so much.

Naturally, it was to be a party of special magnificence.

The good folk of Wellington were beginning to line the streets, bringing picnics and an unusual air of excitement for such an imperturbable race. Some had even camped out overnight. It felt like a public holiday, or a homecoming parade. And in some senses that is exactly what it was. By the afternoon, over 125,000 locals were crammed ten rows deep on either side of the streets — quite something for a city with a population of 164,000 — their ranks swelled by out-of-towners (decreed honorary Wellingtonians for such an occasion), many wearing homespun wizard hats and Elf-ears, who had crammed themselves onto long-haul flights from every corner of the world just to be here on this day. You could hear the noise halfway to Wanganui.

Soon enough the stars and filmmakers would glide through the city, setting off from Parliament House on Lambton Quay in a fleet of Ford Mustang convertibles, soaking up the adoration of the crowd with a royal wave, flanked by Gondorian cavalry, enshrouded Nazgûl on stoic horses, pug-ugly Orcs hefting Weta-made swords, beefcake Uruk-hai, supermodel Elves, and dancing hobbits trying not to trip over their outsized feet. At their head, in deference to the country that had become Middle-earth, was an outlier of Māori warriors with florid tā moko tattoos and waggling tongues. They might as well have been another extraordinary tribe dreamed up in leafy Oxford, a million miles away, in the mind of a pipe-smoking don.

When Orlando Bloom wafted past accompanied by Liv Tyler, there was screaming of a kind that was once the preserve of Beatlemania. There exists a framed photo of the four young actors who played the heroic hobbits — Elijah Wood, Sean Astin, Billy Boyd and Dominic Monaghan — that they had made for Jackson’s birthday. They are in their hobbit wigs, Shire garments and prosthetic feet, but playing instruments and posed exactly like John, Paul, George and Ringo. ‘The Hobbits’ is emblazoned on the bass drum. The Beatles are Jackson’s favourite band, and had themselves once pondered making their own version of Tolkien’s epic as a musical extravaganza.

New Line had reputedly spent millions on the last official world premiere of the film trilogy they had staked their future on. What an inspired decision that seemed now. Had any film in history received a welcome like this? Bob Shaye, the tall, graceful, slightly bohemian CEO of New Line, would sit alongside Jackson in the lead car, the man who had taken the chance on this young director. It hadn’t been the easiest relationship. Hollywood’s risk-averse mentality was not an ideal mix with the natural Kiwi courage to take on the odds. There would be further tensions to come. For now, Shaye and his partner Michael Lynne’s gamble on the impossible book, which had seemed so foolhardy if not outright suicidal to their peers, had that shimmer of Hollywood history about it. That sense of divine obsession on which the movie industry was built, where for every Gone with the Wind there was a Heaven’s Gate.

Figurative tickertape was raining down on Wellington; it was the stuff of dreams with the city’s favourite son capturing it all on his video camera. He knew he would never remember it all, it would pass in a blur.

They had made it to the Moon and back again in filmmaking terms. The Return of the King, a fantasy epic, that laughably unsophisticated genre, would soon pick up eleven Oscar nominations. This was the culminating chapter in a staggering, and staggeringly successful, adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, considered for so long as impossible to capture on film.

Helen Clark, New Zealand’s prime minister, the day’s host, would give her thanks for all the films had brought to this country. Not only Hollywood dollars and employment — when the accounting was done the films would have utilised the talents of 23,000 Kiwis — but the tourism boom his trilogy of marvels had launched. With the help of a different world Jackson had put New Zealand onto the map.

How proud his country was of him, she said. How much she hoped his success would continue on into the future.

Jackson too would address the crowd, giving his thanks and saying how humble he felt that so many of them would turn out. He wasn’t even an All Black.

Everyone would give speeches. Each roared on by the crowd. It was like a wedding or a coronation, with 2,500 specially invited guests. Only this time Viggo Mortensen wasn’t expected to sing.

*

Earlier that day, amid the bustle of party business, with various planners and executives clamouring into walky-talkies and lumpen Nokias, Jackson had dutifully arrived on time at his allotted meeting point. Then, he hadn’t had to travel far. His home in Seatoun was barely ten minutes away, twenty if you caught Wellington at rush hour when the tailbacks can stretch to as many as ten cars long.

Seatoun lies on the seaward side of the quiet Wellington suburb of the Miramar Peninsula that plays home to Jackson’s filmmaking empire — studio, offices, post-production facilities, Weta Workshop, Weta Digital. Hollywood visitors still had trouble seeing past the corrugated iron roofs, brick warehouses, and general disrepair of the former paint factory on Stone Street. Outwardly, barring the immediate beauty of the landscape, everything here seemed so … Well, so unlikely.

How unlikely too that, in all their planning, no one had thought what to do with their director, the man who had made all this happen, while the final arrangements for the premiere were being made. So it was that Jackson had been guided to a perfectly nice hotel suite to wait in a celebrity holding pattern while the more rigorous demands of readying film stars for a public appearance took place elsewhere.

The memory still strikes Jackson as strange. ‘I thought, well, that sounds nice. I thought there would be the actors, but it was just me, and they shut the door. And I was sitting in this hotel room for at least an hour and a half. I was lying there thinking, this is pretty weird. Why aren’t we having a drink down in the bar?’

He was as nervous as anyone would be about to speak in front of hundreds of thousands of people. A drink, a laugh, simply passing the time with someone would have helped.

What might have struck him as strangest of all, however, was that he had been left to his own devices. As long as he stayed put. New Line’s army of wedding planners weren’t going to let their prize catch wriggle free. They virtually put him under lock and key. Gandalf imprisoned on the roof of Orthanc.

Only hours before, with the eleventh hour disappearing in the rear-view mirror, had he completed his adaptation of The Lord of the Rings trilogy. With a running time of three hours twenty-one minutes, long even by his own extended standards — and even then he knew that fans would bemoan the loss of lovely sequences that wouldn’t be retrieved until the Extended Edition a year from now — The Return of the King was ready for its heroic debut. For the first time in five years, maybe longer, Jackson didn’t need to worry about his films.

There was no need to approve any fresh artwork from the peerless and tireless pencils of John Howe or Alan Lee; or clear an effects shot, a music cue, a sound edit, a costume alteration, a set that had sprung up overnight, a mooted location or schedule, a poster design, or indeed head to the edit suite, because when all else was done he always needed to head to the edit. No actors would need to call upon his wisdom; no lighting set-up or shot trajectory was open for discussion. No stunt team needed marshalling. No new script pages needed to be wrestled into submission; as he no longer needed to fine-tune the sometimes-cumbersome complexities of Tolkien’s world toward the dynamic world of cinema — to choose this path or that, often depending on which one smelled the better. Even those public relations folk, who had called upon him to speak to the press when he could least afford the time, were now busy elsewhere.

The constant background noise inherent in this awesome undertaking had finally been silenced — all he could hear was the crowd a few blocks away, cheering even the carpet sweepers.

Jackson was left alone with his thoughts.

He turned on the television and found a telemovie, whatever was playing. He can’t remember what it was about let alone what it was called; he doubts it was any good.

Lying there on the bed, some cheesy, low-budget melodrama in the background, his mind must surely have wandered back through the forest of days, the miraculous events and unaccountable toil that had brought him here to this moment of triumph and farewell.