Читать книгу Daniel O'Thunder - Ian Weir - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJACK

IAM NOT the devil. I need this to be understood, from the outset. If you won’t accept it, then please stop reading. Set these pages aside, and go away. Go and judge someone else.

God knows I am not an angel, either. I don’t even profess to be a very good man, for we are none of us good, not in the way that Heaven yearns for us to be. I am just a man. I have needs and desires, some of them lamentable, for like yours my nature is Fallen. I have from time to time indulged these desires, for like you I am weak. At moments indeed I have walked at the Devil’s side, and heard his sweet seductive whispers, and perhaps even for the span of a heartbeat been his man—as you have—body and soul. But at all times I swear that I have wished to be better. I have prayed to be good, and fixed my eyes upon the image of Goodness Itself that winked and glimmered on the far horizon—so remote from us, and separated by such torturous terrain. I have staggered towards it all my life, and stumbled and fallen, and grovelled for a time and then stood up and staggered some more, though my feet were lacerated and my poor heart ready to burst. Just like you, my friend. Just exactly like you.

Are you still there? Still reading? Wherever it is you like to read—in the comfortable chair in your parlour, perhaps. Or stretched out beneath your favourite tree, with Trusty the spaniel dozing close to hand. Fine: if you’re still reading, then I’ll trust we have a bargain. You will not judge—and I will tell the truth. Or at least you will withhold your judgement as far as seems humanly possible—which is seldom very far—and I will tell as much truth as can reasonably be expected from a man—which is seldom as much as one might hope—and between us we’ll do the best we can.

Yes? Then we begin.

It is 1888 as I write these words. I am an old man now, scratching syllables by candlelight at an old desk in a dingy room in Whitechapel. The wallpaper peels in the ever-present damp, and a filthy window overlooks Dorset Street. Sometimes I write of the Devil, and of his activities amongst us in London some decades ago, my connection to which may grow more clear as we proceed. But mainly I write of a man named Daniel O’Thunder. I write of Daniel as I knew him, and since no man may know the entire truth about anyone or anything, I have collected as well the accounts of others. In some cases these have been set down in writing by the teller. In other cases I have had to go beyond an editor’s role and conjure the tale as the teller would surely have told it, had he or she the opportunity. In these instances I have relied scrupulously upon such details as have been made available to me, supplemented where necessary with judicious suppositions and my own insights into human nature. In short I may here and there have invented certain facts, but always in the service of a greater Truth. As indeed did Matthew and Mark and Luke and John—and every single word they wrote was Gospel.

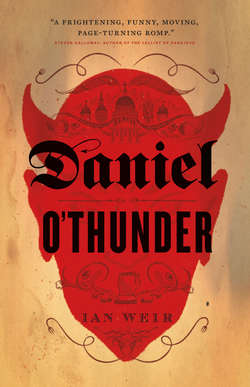

Daniel O’Thunder was—and remains—the most remarkable man I have ever met. He was a complicated man of deep and abiding contradictions, and yet he was at one and the same time a simple man with a very simple goal. He wanted to call the Devil forth, and face him and fight him, and—finally and forever— defeat him.

This, then, is my Book of Daniel.

In writing it—in telling you the tale of Daniel O’Thunder, and his deadly Enemy—I am of course telling the tale of myself as well. And to tell my story we must begin where it all began to go so wrong.

A SUNDAY MORNING in 1849. We are in Cornwall. More specifically we are in the little church of St Kea’s-by-the-sea. It is a church in the stark Gothic Perpendicular style, dating originally to Norman times, set upon a hillside above the village of Porthmullion. The churchyard is a riot of colour, for it is spring and the daffodils have begun to bloom amidst the headstones. There is a towering grey Cornish Cross outside the front door, carved atop a granite column. Nearby is the Holy Well where miracles were wont to occur in bygone days, and might—we are Christians, and live in hope—occur again. Here inside the church it is cool; it smells of damp and piety and distant sea-brine. Sun slants in through stained glass, and dust-motes dance like angels. Mounted upon the walls are slate tablets with inscriptions commemorating bygone parishioners, such as young William Barnstable:

Short blaze of life, meteor of human Pride, Essayed to live, but liked it not and died.

In the windows are Bible scenes, and images of the Four Evangelists. Set into the west wall is a portrait of St Kea. His golden head is haloed, and his eyes glow with an unsettling admixture of humility and fervid derangement. This conceivably reflects the limitations of the artisan, but possibly it doesn’t, St Kea being one of those Dark Age divines who paddled to Cornwall from Ireland on a boulder. There is in Kea’s expression a certain agitation as well, an incipient alarm, as if he glimpses Someone Else amongst us, and would call out a warning if only he weren’t trapped forever in stained glass.

The saint is quite correct, of course. The Devil is here, and he is watching. He’s watching dear old Petherick, the verger, nodding off in the choir. He’s watching young Bob Odgers—pay attention, Bob, and stop pinching your sister. He’s even daring to watch Sir Richard Scantlebury, Bart., slumbering in his family pew. Oh yes he is—open your eyes, Sir Richard. Beware! He’s watching right this second.

And on that fine spring Sunday, looking out from the pulpit in my cassock and my jampot collar, I told them so. Behold the young Revd Mr Jack Beresford, in earnest oratorical flight.

“For the Devil does not sleep,” I said, “and he does not blink. The Devil’s eye is a basilisk’s eye, and it is fixed upon you, and you, and you, and upon each and every one of us, from the moment we draw breath until the moment we are Judged. And if in this Judgement we are found wanting, then that eye will remain fixed forever.”

In a different parish such ruminations might well have been seen as alarmingly Low Church, or indeed slightly mad. But here in St Kea’s there was a little frisson of dark satisfaction. Mine was a congregation composed primarily of labourers and fisherfolk. Cornish labourers and fisherfolk to boot, dour and stolid men and women who quite liked the idea of their neighbours being Judged, especially if they should also be Found Wanting.

“Now, I have met with those,” I continued, “who maintain that the Devil does not exist. They say to me, ‘surely the Devil is just a story, made up to frighten children.’ And what do I say to this? I say: ‘my friend, if you don’t believe in the Devil, then I’m not sure I believe in you. For if you looked at yourself closely—if you looked down deep in your heart—I suspect you’d see a devil soon enough.’”

I happened to be looking straight at Sir Richard, Bart., as I said this, which was unfortunate. Sir Richard, Bart., had awakened with a snort and a fart a moment or two earlier, and he was a man who felt perceived insults keenly. The Scantlebury pew was curtained and carved and raised above the rest to balcony level, for the Scantleburys were the local aristocracy—which is to say that they were a clan of inbred horrors descended from smugglers and pirates. Sir Richard’s great-grandfather was the notorious Reeking Scantlebury, a freebooter equally noted for his rapacity and his contempt for personal hygiene. He married Black Bess Timberfoot, a twenty-stone one-legged pirate queen who was known for flaying her captives alive and feeding their vital organs to her parrot, Beaky Norman. From them are descended the present generation of appalling pig-farming gentry.

Granted, I’m supplying one or two details of my own here. Such as the parrot, and the pirate queen, and Reeking himself. As you come to know me better, you will learn that I have a vivid imagination, and an instinct for the dramatic. Still, many Cornish fortunes did indeed begin in smuggling, and these guessed-at details would go a long way towards explaining the present occupants of Scantlebury Hall. Sir Richard was a man of porcine bulk and ponderous self-regard, sitting like a champion boar amidst his brood. On his right scowled the son and heir, Little Dick, half a head taller and even broader athwart. Beside Little Dick was young Geoffrey: a pouting thing of twelve or so with a head of yellow curls, proof that the breeding of sons is not as exact a science as the breeding of Dorsetshire Saddlebacks, and that even the saltiest sea-captain may sire the occasional cabin-boy. On Sir Richard’s sinister side sat Bathsheba, the most unsettling Scantlebury of all.

Bathsheba Scantlebury was one-and-twenty. She was her father’s daughter, and clearly destined for the Scantlebury bulk, complete with the squinting Scantlebury eye and perhaps even a wen upon the snorting Scantlebury snout. But not yet. Bathsheba was still beautiful—or if not precisely beautiful, then nonetheless keenly desirable, in an ill-tempered sluttish up-against-the-cowshed sort of way. She had a gaze that pinned you wriggling to the wall, and a curl to her lip that said: “I know what the world is like, and what it wants in its filthy black heart—and more than that, I know you.”

I gripped the sides of the pulpit and continued, like a mariner in his cockpit gazing down upon a troubled sea.

“You say to me, ‘Mr Beresford, I have looked high and low—I have looked within and without—and I have never seen the Devil, no not once.’ Well, I’m afraid I must reply that this is very bad indeed. For if you don’t see the Devil, what it almost certainly means is, he’s already got you.

“For the Devil is a busy man, my friends. The wide world is his hunting-ground, and all of humankind his quarry. So when he passes a hardened sinner, he exults: ‘This one is already mine— pass on to the next!’ A grasping man of business, extracting the last mite from a widow? ‘Pass on.’ The man and the woman eyeing one another, aglow with the secret fires of lust? ‘Well done, my good and faithful servants—you’ll join me soon enough, and my flames are everlasting. Pass on!’ So take no solace when you cannot see the Devil, and never suppose that he has forgotten you. For the gates of Hell are gaping wide, and the Devil is forever rising up.”

I shot a swift guilty glance upwards to Bathsheba Scantlebury. Her own eyes had widened slightly—for damn it all, these infernal musings had provoked a certain agitation down below, and the Devil was rising up indeed. The pulpit hid this from most of the congregation, but Bathsheba in the elevated Scantlebury pew stared down from above. And she had seen.

Oh, Lord. I could hear my voice growing constricted, and sought refuge in shrivelling images.

“Once the Devil has risen up, he will not rest until he has dragged you down. And what does it mean, to be dragged down by the Devil? Well, let me tell you. You are sealed in your coffin, and plunged head downwards into the Pit. And this Pit is like a mine shaft, except far narrower, just wide enough to accommodate your coffin, which in turn is so close that your face presses up against the wood, so tightly that you cannot draw a single breath, even if there were air to breathe in Hell, which there is not. There you are, pinioned upside-down, suffocating in the stench of the unquenchable sulphur flames—and yet ice-cold, a cold that gnaws into your very pith and marrow, for the flames of Hell generate no heat, but a cold so intense it cannot be conceived.

“And there’s worse to come. After an age of agony, there comes an instant of hope. You hear a scraping sound above, and a voice crying, and your poor heart leaps with the thought: ‘They’ve come to fetch me out of this!’ Your coffin gives a lurch and a shudder and a grind, but the cry you heard was not the angels winging to deliver you. It was the sinner next in line, who has just been loaded in on top. An endless line of sinners, each one atop the last, each one forcing you six feet deeper down that suffocating shaft.

“And now comes the worst of all. You realize: you are utterly alone. God has turned His face from you—now, and for all eternity. God has forgotten you ever existed. He has let you go.”

I had shaken them. I could see it in the faces staring back at me: some of them slack-jawed, a few of them frankly appalled. Even Sir Richard blinked, and shifted his bulk uncomfortably. I could have continued. I could have told them: trust me—it’s true— I know. I’ve read my Calvin and my Dante, and a hundred hellfire evangelists beside. What’s more, I’ve looked into my own heart, and understood what I deserve. I felt the prick of tears, and there was a moment—there really was—when I might have fallen to my knees, and wept, and confessed my sins to God and the people of Porthmullion, and vowed to walk the paths of righteousness all the days of my life.

But Bathsheba Scantlebury was staring down at me. Her head was cocked appraisingly, and her lip said: “Oh, you dog—I know you.”

The Devil stared straight back at her, and twitched.

I SHOULD NEVER have been a clergyman in the first place. That should have been my brother. Tobias was two years younger, a boy who could pray for hours at a stretch, and who would utter things like, “God sees the little sparrow fall, but He trusts in you and me to mend its wing.” He nursed wounded birds in his bedchamber, did Toby, keeping them in a little box beneath a picture of Our Lord holding a lamb in his arms. Our Lord had a tiny sad smile on his face—you know the smile I mean. He smiles because he loves us, but he is sad because so many of us are damned and just don’t know it yet. Late at night, passing by, I would hear the sweet earnest murmur of brother Toby entreating Our Lord to forgive me. Toby was in short a sanctimonious little horror. But just as you were on the verge of ducking him in the pond, he’d finish all your chores and disappear before you could thank him, or else ask you why you were crying and impulsively give you his new compass, or perform some other such act that would send you slinking away with a withering sense of your own selfishness, and the deeply discomfiting realization: my God, he actually is good, isn’t he?

In this he took after our maternal grandfather, an ineffectual but beloved provincial vicar who occupied pride of place in my mother’s personal canon of saints. So when Toby announced—at the age of three—his vocation for the priesthood, it was a day of rejoicing for my mother, not to mention a vast relief to me. Now that Toby’s chubby hand had taken up the torch, I was free to follow my own true nature, which much more closely favoured our father. He was a provincial solicitor—we lived on the outskirts of a bleak Midlands industrial town, whose belching smokestacks fed my child’s intuition that Hell’s Gate was just beyond the next hill. More to the point, my father was the second son of a second son, a man of feckless charm and determined demons who frittered away a modest patrimony in a sequence of ill-conceived initiatives. After each catastrophe he would plunge into drink, proceeding through fury to despair and tearful encomiums to self-slaughter, before staggering back to his feet in the renewed conviction that something grand might turn up next week.

But my brother never took up holy orders. A chill gripped Toby on the evening of his fifteenth birthday, and he withdrew to his chamber under the sad watchful gaze of Our Lord. By morning the chill had become a racking cough, and by nightfall a fever that made the doctor shake his head in gloomy resignation. Toby departed at dawn, brave and devout, actually whispering with his last breath: “Don’t cry, Jack. Look—my angel’s come—he’s reaching out to take my hand.”

Well, this is quite the legacy to leave your older brother. I was seventeen at the time, and had almost settled upon the Law as a suitable career for a young man with decent intelligence and keen material expectations, but no particular gift for application—my father’s son, in other words. But now the weight of maternal hope had nowhere else to fall. My poor mother was sufficiently distraught to clutch at any straw, even the belief that I might make a clergyman after all—so how could I say no, with the flowers still fresh on Toby’s grave? Besides, I was genuinely haunted—and have remained so, all my life—by the look on my brother’s face as he struggled to lift his hand towards his angel. It was a look so radiant that it could make even a wretched Doubter half-believe that it was true—that Toby’s angel was there—and more, that there was a second angel in the room, reaching out to Toby’s brother and telling him: “This is your destiny. Put down your nets and follow me.”

So. You conjure consolatory dreams of deanships and bishoprics, which soon wither in the reality of a third-class degree from Oxford and a family with no money and less influence. Finally the Future presents itself in the form of a seventy-pound-per-annum curacy in the outer reaches of Cornwall. And what do you do then? Why, you do your best.

MY BEST IS WHAT I was doing on the afternoon of that fateful Sunday.

I had spent an hour or so alone after service, despairing over failures and inadequacies, and dreaming of escape. Today’s dream had to do with California, whence news of a Gold Rush had reached the newspapers even in Cornwall. This conjured an agreeable image of myself, ministering selflessly to spade-bearded miners in a verdant wilderness, before succumbing to a fever even more spectacular than the one that had taken my brother. I had just come to the point where news of my death reached Bathsheba Scantlebury—she was secretly shattered—when I saw that the hour was nearly two o’clock. God’s Work awaited just down the road, and so I gave myself a shake and roused myself to it.

Old Ned Moyle had been failing badly these past few months. He was past ninety and no longer able to walk to church, so I’d fallen into the habit of taking the Communion bread and wine out to him. This meant a five-mile trudge along the cliffs to the fisherman’s cottage where Old Ned lived with his son, Young Ned, and then of course a five-mile trudge back, which was no bargain—let me tell you—when the weather was up. But on a fine spring afternoon, I confess I enjoyed it—a walk that was all sharp salt air and plunging ocean vistas, with prowling waves and secret coves where you could picture low-slung sloops at anchor under the black flag, and Reeking Scantlebury plotting his depredations, and Black Bess in the fo’cs’le feeding your kidneys to Beaky Norman.

The Moyles lived in the sort of rough dwelling you’ll find all along the Cornish coast, clinging to the rock like barnacles. Their low stone cottage was set into the hillside, with a steep path winding past a desultory vegetable garden and down to the sea. The sun was sloping westward when I arrived. Young Ned was at work out front, mending his nets. “Why, it’s the young Reverend, coom to zee us,” he exclaimed, as surprised as he had been last Sunday afternoon, and each Sunday afternoon before that. Young Ned was well on the shady side of seventy himself—still as strong as a bull, but his memory was no longer what it once had been. The result was that life was full of surprises for Young Ned, and some of them were pleasant, which I suppose must count as a blessing.

“Coom in, young Reverend,” he beamed, wringing my hand and leading me inside. It was cramped and damp but surprisingly clean, though full of clutter and fisherman’s paraphernalia. The stick that was Old Ned reclined in a cot by the window, covered with a tatty old shawl. I performed the Eucharist with my customary sense that someone else would be more convincing in the role, pausing as usual while Old Ned gummed the wafer and worked it down. Afterwards I stayed for a chat, which was identical to the chat we had enjoyed the previous Sunday, and all the Sundays preceding, the gist being as follows:

YOUNG NED: “Well, Da. Here’s the young reverend.”

OLD NED: “It’s the legs, you know. They’ve give out.”

REVD BERESFORD: “I’m afraid God sends these things to try us.”

OLD NED: “WHAT?”

YOUNG NED: “E ZAYS, GOD ZENDS THESE THINGS!”

OLD NED: “Aye, God zave the Queen.”

(Brief interlude, in which are vague patriotic noddings.)

YOUNG NED: “Well, Da. Here’s the young reverend.”

Et cetera. The chat lingered, as it often did, owing to the excellent quality of Young Ned’s ale. We toasted the Queen, and the Prince Consort, and various heirs to the throne, and it was well past five o’clock by the time I rose and blessed Old Ned— something that always made me feel utterly fraudulent, but also oddly happy. Young Ned walked me out to the head of the path. It was clear there was something on his mind, and I waited while he hummed and hawed.

“’E’s not entirely well, is ’e?” he said at length, with a sidelong look, as if half hoping that I might contradict him.

“He’s an old man, Ned,” I said. Sometimes it’s best to stick with the blindingly obvious.

“’Is legs’ve give out.”

“His poor old legs.”

“Aye. Them legs.”

Young Ned stood pondering his father’s legs for a few moments, rocking from toes to heels, sucking ruminatively upon his teeth.

“But it’s more than that, isn’t it?” he resumed. “I’m ztarting to think . . . ’e might be gone, one of these days. One of these days quite zoon.”

There was such wistful look in his eyes—a man of more than seventy, about to be orphaned—that my heart went out.

“We’ll all be gone one of these days, Ned. But here’s what I think. I’m pretty certain—I think I can say for a fact—that he’ll be here when I come back next Sunday afternoon. So we’ll raise a glass of your excellent ale, and we’ll toast Her Majesty and all her loyal subjects, and we’ll spend a splendid afternoon.”

Sometimes when we open our mouths, the right words come spilling out. Young Ned began to nod, a happy look creeping across his weathered old face. “Well, young Reverend,” he said. “We’ll all look forward to that.”

I LEFT WITH a feeling of warmth inside that wasn’t entirely due to Ned’s ale. For a few lovely moments I was buoyed by the sense that God’s business had just been carried out—and carried out by me—and that against all odds I might actually have a vocation for this after all. I imagined Toby and his angel smiling down in dewy-eyed approval, and all at once I felt a powerful urge to go searching for fallen sparrows. But this passed, for the weather was turning.

It was later than I’d intended. Twilight was creeping across the hills, and with it came a rising wind and dark clouds massing overhead. I pulled my coat more tightly round myself and hurried; you didn’t want to be caught on the cliffs after dark, especially with a storm rising. I had reached the crest of the headland, just where the trail grew narrowest and the rocks plunged most precipitously into the sea below, when I heard the sound of hoofbeats behind me, emerging out of the roar of wind and waves. I looked back, and shouted in alarm, for the rider was already upon me.

“Look out, you fool!”

This being the rider’s shout, not mine. A moment later I was raising myself to hands and knees, winded and indignant, having sprawled for safety half a heartbeat before the hooves thundered past. Ahead, the horse was brought skittering to a stop.

“I say, look where you’re going—you could have killed me!”

“Then stay out of the damned road!”

A great grey gelding shied and pranced, and I recognized the rider. It was Bathsheba Scantlebury, in tall black boots and a black riding cloak. She gave a little start as she recognized me in return.

“Is that the curate?” she exclaimed.

She brought the horse skittering closer, to be sure.

“The Revd Mr Beresford—it is you. What the Devil are you doing up here on the cliffs, with a storm coming on?” Her hair was loose, and her colour was high with the wind and the gallop. Cocking her head, she eyed me with jaundiced appraisal. “I’d best not discover you’ve been poaching.”

“P-poaching?”

You try getting the word out without a splutter—an accusation like that, when you’re already fair dancing with the indignation of it.

“This is all Scantlebury land. Lay a hand on a single pheasant, and I don’t care who you are—I’ll have you horsewhipped.”

“You sulky supercilious bitch,” I cried—or at least, imagined myself crying. Indeed, I imagined stalking forward in seething masculine dudgeon, and saying other things besides, such as: “You’re the one who should be horsewhipped, Miss Scantlebury. I’ve half a mind to turn you over a knee myself—and I see by the wanton gleam in those eyes that you might jolly well like it!”

But of course I said no such thing, being a man of the cloth.

“In point of fact I’ve been to see a parishioner,” I said, clutching what tatters of dignity I could lay hands upon. “Not that it’s any particular business of yours. I just walked five miles to comfort the afflicted, and now I’m walking fives miles home again. That’s what a priest does, Miss Scantlebury, because that’s what the Lord expects of him. I am also called to feed the hungry,” I added, “and clothe the naked.”

Damn. The instant it was out of my mouth.

One eyebrow arched. “Yes, I can well believe that the naked concern you, Mr Beresford. I suspected as much this morning.”

I could feel the morning’s humiliation rushing scarlet to my face. And she just looked at me, brazen as Babylon.

“Come on, then—I won’t leave you out here in a storm. Climb up, and you can ride behind.”

But a man has his pride. I straightened my back, and met that gaze with actual—yes—froideur.

“Not if yours, Miss Scantlebury, was the last behind in Cornwall.”

I admit, an unclerical thing to say. But by the God who made me, it was splendid to say it. Bathsheba’s jaw actually dropped, as she searched for a suitable retort. But whatever it might have been, it was lost in a startled exclamation. Lightning had flickered a few moments before, and now thunder cracked, directly overhead. Her horse, already skittish in the rising wind, reared back; taken unawares, she tumbled.

“Miss Scantlebury!”

She was on her back and rolling, and in another instant she must have gone straight over the cliff-edge. But I had already leapt forward, and caught her by the arm to steady her. Bathsheba lay breathless for a moment, stunned by the fall and by the narrow escape—for this had been a near-run thing. We stared down at the jagged rocks and the heaving sea far below.

“Are you all right?”

“Take your hands off me!”

I released her and stepped back, expecting her to stand. Instead she lay where she was, gasping for breath and glaring furiously up at me.

“I’ve hurt my leg, damn you.”

“That’s hardly my fault.”

“I damned you on general principle. I say it again: damn you, and damn that look you’re giving me right now. That’s supposed to be manly concern, is it? And I suppose you think you’re fetching—the young curate, with his soulful eyes. Well, don’t bother, because I know you.”

I hesitated. “May I . . . ?”

“No, you may not!”

But I did. I knelt and asked which leg was hurt, and she lifted the right one an inch or two. It seemed to be her ankle—a surprisingly delicate ankle, at the end of a beautifully formed calf, above which there was of course a knee and—oh dear God. “I don’t think it’s broken,” I hazarded. But clearly it was badly sprained, for the gentlest touch made her gasp, and when I glanced up her eyes had actually filled with tears. For a heart-stopping moment she was a child again, hurt and vulnerable and secretly frightened.

“What do we do now?” she asked, for clearly we faced a dilemma. Her horse was already gone and galloping homeward, and here we were—a good two miles from the Moyles’ cottage, and at least another three from Porthmullion, with night falling and the storm beginning to rage in earnest.

“Lean against me,” I urged, helping her up. “Here, we can manage it!”

But we couldn’t. This was clear enough after the first few hobbling steps, which left just two possibilities. The first was to leg it for home myself, leaving Bathsheba to rot—which I confess I considered. The alternative was an old abandoned shepherd’s hut. It was above us, in a cleft between two hills.

I pointed. Rain lashed down, and I had to raise my voice against the wind. “It isn’t much, but at least there’s a roof. It’ll keep us dry while we wait out the storm. Look, I’m going to have to carry you, all right?”

“I swear, I really will have you horsewhipped!”

Which under the circumstances I interpreted as agreement.

The uphill path was arduous, and several times I nearly fell. But as I struggled onward—her arms round my neck—I began to see myself as I still do, frequently, to this day: as an actor thrust into a role upon the stage, wholly unprepared and fearing himself unequal to the task, but plucky and determined and finding his light, and discovering resources that he had never dared hope he possessed. I believe I had an image of myself as the hero of one of Mr Boucicault’s melodramas—the one in which he rescues the foul-mouthed slut. But after an eternity of slips and strangled oaths and “Christ, watch where you’re going, you imbecile!”, the old stone hut was there before us, and we staggered in.

It was small and dank, and it smelled of piss, but it had a roof, and a door that pulled shut with a tattered leather strap and kept out the howling wind. There were even a few sticks of furniture. I kicked apart a rickety chair for kindling, and after a few attempts I managed to start a little fire, which crackled and generated actual warmth. We stripped off our sodden cloaks and huddled in front of it. I discovered I still had half a jug of ale, and this improved things even further.

“Young Ned gave it to me, before I left. Young Ned and his father—that’s who I went to see.”

“You mean you really were seeing a parishioner?”

I wasn’t offering it as proof that I’d been telling the truth, but apparently she took it as such.

“Do you want to search my pockets for pheasants?”

“Oh, don’t sulk. You think it makes you look dark and brooding, but it doesn’t.”

Her expression was sour, but there was also a certain—well, if not warmth, then at least neutrality. She was sitting on an old blanket that I’d found on a shelf and spread out in front of the fire. Her dress clung to her, and as I uncorked the jug I caught her sneaking another sidelong look in my direction.

The fact is, I was a good-looking fellow in those departed days of 1849. It wasn’t the face I show to the world these four long decades later, ruined by the years and much else besides—a face that would cause you to start if you saw it, and flinch. For that’s what you would do—oh yes you would—if I looked up abruptly from my glass in some low tavern, or perhaps came upon you suddenly in the London fog. But back then I was quite the lad, in a crookedly smiling boyish sort of way. The brown eyes were large, and there was a wing of brown hair that would fall down over them, which I had a way of flipping back with a movement of my hand. The overall effect might indeed have been too boyish, except for the scar: a horseshoe-shaped scar by my left eye, courtesy of a childhood set-to with a butcher’s apprentice who had been bullying my brother. I’d been carried home in a cart, to be sewn up on the kitchen table, but apparently I’d inflicted some damage in return, for my adversary never troubled poor Toby again. And I afterwards discovered that the girls were quite affected by my scar—it gave me a rugged cast—so all in all I decided I’d come rather well out of the bargain.

Miss Scantlebury and I shared the ale, and divided the loaf of bread and the lump of cheese that I’d brought with me too. Soon enough we were feeling warmer, and beginning to talk. Then we were talking some more, and laughing, and agreeing that this was a very odd place for a picnic. I found myself telling her about the old Welsh pony I rode as a boy, and never saw the Devil until it was too late.

“The last behind in Cornwall?” She eyed me aslant.

“Yes, well. I apologize,” I said. “That was rude, and ungentlemanly.”

“I shouldn’t forgive you,” said she, with a little pout. “But under the circumstances, I suppose I shall.”

“You’re very good.”

“No I’m not. I’m not very good at all. That’s what you like best about me.”

“Miss Scantlebury, what are you doing?”

For a hand was upon my leg.

You’ll have guessed the sequel, of course. Someone like yourself, who knows the way of the world and the frailties of the human heart. And of course I knew it was wicked, and wrong, and hateful in the eyes of God. But the Devil had slipped in from the storm without our noticing, and now there was the dark sweet murmur of Infernal blandishments—go on, my friends, for you want to so much; it’s lovely, it’s harmless, and who’s ever to know, on a night so dark and God’s eyes surely elsewhere?—and then the lash of his riding crop. Before I quite realized what was happening, Bath-sheba was a wondrous writhing rubbery thing. Breasts burst from linen; she cried out. The first hot cascading plunge, and finding the stride, and then the great gallop—ears pinned back and the Devil’s whip-hand flailing—thundering around the turn and down the stretch to the last gate, the storm raging both within us and without. We were up and over and tumbling down the other side, utterly spent and lying limp as rags. And then, just as triumph began to give way to the first cold stabbings of remorse— that familiar sick lurch into self-loathing—just at that very point, I felt an icy gust of wind. The door was open, and someone was standing in the doorway, holding up a torch.

“Bathsheba?!”

It was her younger brother, the Cabin Boy. Behind him loomed Little Dick. I exclaimed, grabbing at the blanket to cover myself. Despite my confusion, I expected to hear Bathsheba’s voice, uttering furious oaths and ordering them out.

“Help,” whispered Bathsheba.

“I beg your pardon?” I said, bewildered.

“I tried to fight him, but he forced me.”

“I did not!”

“Oh God, oh God, oh God, my Virtue.”

I sprang to my feet. But a sledge-hammer fist came whistling, and the world exploded into blackness.

THIS IS WHERE my account grows unreliable. The memory of what happened next has the swooning unreality of nightmare; I have been forced to conclude that some of it—much of it?— was pure hallucination, brought on by that first concussive blow. But I have pledged to tell my tale to the best of my ability, and so here is what I seem to recollect.

I am swimming back to consciousness. A vast echoing room, with great rough wooden beams, lit by torchlight. A cavernous fireplace, and tapestries on the walls, and animals stuffed and mounted: the heads of stags and boars, and the entire forms of smaller predators—ferrets and badgers and stoats—frozen forever in attitudes of coiled malevolence. Among these are human portraits: bloated grandsires with bulging eyes, and cold-eyed viragos as coiled and malignant as the stoats.

Even in my disorientation, I can guess whose ancestors these were. This shrine to slaughter and misanthropy is Scantlebury Hall, and here assembled are the current denizens. Sir Richard on a vast oaken chair, with Little Dick louring beside him. Bathsheba recumbent nearby on a low divan, wrapped in a blanket and managing to look shattered, attended by the curly-haired Cabin Boy.

I struggle to my knees.

“Look here,” a voice says woozily, as if from a good distance. Apparently it is mine. “I don’t—you can’t just—dear God in Heaven.”

The voice that replies is like metal grinding upon stone. “The charge against you is as follows. That you did lie feloniously in wait for a virgin of unimpeachable character, viz. my daughter, upon whom you did perpetrate an act of savage assault and rapine, in such a manner as to place you beyond any appeal to common humanity, and all hope of mercy in this life or the life to come.”

Sir Richard Scantlebury, Bart.

“A charge? What are you talking about?”

“How do you plead?”

“I didn’t touch her!”

This is not of course strictly true. A stammered emendation: “I mean, yes, of course I—well, you know. And it was wrong— a priest—obviously. A shitten shepherd—a disgrace to the cloth—I condemn myself utterly. But we walked down that path together, and I swear I am not the sort of man who would ever—just ask her!”

“You ask me to believe,” grates Sir Richard, “that my daughter— what—seduced you? That she participated in the act? Of her own volition, and without protest?”

“Yes!”

They stare: a convocation of stoats contemplating a rabbit.

Bathsheba’s bottom lip quivers.

What happens next is assuredly an hallucination. I seem to see young Geoffrey stepping forward. Inexplicably, he seems to be wearing a peasant smock and carrying a basket of baguettes. He points a finger in righteous venom, as if standing in the shadow of the guillotine.

“J’accuse,” says the Cabin Boy.

“What?” I exclaim, bewildered. “What’s he saying?”

The room gives a lurch, and steadies. Geoffrey is himself again, and he is lying through his teeth.

“ . . . and I was hurrying home with my brother, Sir, when I heard my sister screaming. We ran to help her, thinking she was being murdered by ruffians, or tortured by Red Indians, so terrible was the cries. Instead we found her in the embrace of the curate, him standing right there, rutting in his lust with his bottom bare and horrible, and shouting, ‘Scream all you please, my Pretty, for I only like it better when you do!’”

All eyes are upon me. Sir Richard and his brood, and their ancestors upon the walls, and the ferrets and the stoats. Such eyes as I have glimpsed in my darkest dreams of perdition.

“Do you have anything to say,” says Sir Richard, “before sentence is passed?”

“Sentence? This is no court!”

“This is the manor court, convened by ancient baronial privilege, and I am the baron.”

“You’re all mad!”

Or else I am. But things are happening very swiftly now.

“Kill him!” cries Bathsheba, bursting into tears. “Kill him—but geld him, first!”

Little Dick reaches out. But in moments of crisis we discover what we are made of, and this moment confirms what had been intimated in the Battle of Butcher’s Apprentice—to wit, the Revd Mr Beresford is descended from warriors. If not actual warriors, then at least the sort of men who could survive a skirmish on the fringes of the main conflagration—men who could raise their heads a few breathless moments after the last cannon had echoed into silence, and look around, and blink, and exclaim: “Are we done, then? By the Lord Harry, that was almost too close for comfort.”

I duck my head and charge, butting Little Dick in the solar plexus. He staggers back, trout-faced. The window—quick! The Cabin Boy skitters to block my way, too late. A bound and a leap and a shattering of glass, and I am through the window headlong and landing with bone-jarring impact.

All air is driven from my lungs. Howling wind and lashing rain. Somehow I am back upon my feet. But there are shouts behind me, and a gunshot. Christ! I am running now, running blind. Then the ground is gone beneath my feet. I pitch forward. A sickening sensation of falling—and falling.

Even in my wild confusion, I know what this means. There is a sheer cliff on the windward side of Scantlebury Hall, and I have blundered over. Now there is nothing but the icy black sea and the jagged rocks below.

But now comes the most incredible moment of all. I swear this to be true. In that moment of horrid realization—plunging helpless, like a minor rebel from the fields of Heaven—there is a light in the darkness. I seem to see a shining face, and a hand reaching towards me. In my confusion it seems to me at first that this is the visage of blessed stained-glass St Kea, paddling to my deliverance on a boulder. But it is another face entirely. A man’s great laughing face, lumpen and scarred from old battles but somehow beautiful nonetheless, with a lopsided jaw and a tumult of yellow hair. The face of a warrior archangel, and a voice like the flight of eagles, saying: “Fear not, brother, no never fear at all, for I am with you always.”

“Who are you?” I cry.

He says: “O’Thunder.”