Читать книгу Daniel O'Thunder - Ian Weir - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление• LONDON, 1851 • NELL

IT WAS EARLIER that night when I seen the Devil, outside the theatre. The Kemp Theatre, north of Holborn, near King’s Cross. He was on the corner, passing out handbills. Or not the Devil himself, but one of his demons, spindly and wretched and black with sulphur smoke. Leastways that’s what I assumed, cos what else would he be, outside a theatre? An actor, got up as one of Satan’s henchmen, passing out handbills for the play.

But he wasn’t. I realized when I got closer and looked again— the sulphur smoke was ink. So he was a printer’s devil, an apprentice in a print shop. Apparently he wasn’t much good at it either, cos he’d got inkstains all over. He was skinny and shabby, with hands that stuck out the ends of his sleeves and trousers that come halfway up his shins, and it wasn’t handbills for the play he was giving out. It was tracts—you know, the Christian ones, all about living a better life and what happens to you if you don’t. Well, I don’t live the one, so I can hardly afford to care about the other, can I? So I ignored him and elbowed my way in with the crowd, and I’d never have give him another thought the rest of my life, if it hadn’t been for what happened later.

I always loved the theatre. I loved it more than practically anything. Back then, all those years ago when I lived in London, I’d go nearly every night of the week. I’d go see any kind of play, even Shakespeare. I seen Charlie Kean play Hamlet once, and Macready, and afterwards I went with one of them. Not Kean or Macready, but one of the others. We went to a night house nearby, and had a drain or two of pale, and then took one of the little rooms. Nothing happened much, even though I gave it a good try. It just dangled there like a wrinkled stocking, between his skinny old shanks. But he paid up like a gentleman, and we drank some more, and he blubbered a bit and called me his own dear child who reminded him of his salad days when he was young and the world was full of hope—yes, he talked like that—so perhaps he got his half crown’s worth. If he didn’t, ah well. Fuck ’im.

But the ones I really liked were the melodramas. Mrs Dalrymple used to take me when she was alive, and now that she was dead I’d go to the theatre with one of the other girls, or lots of times just by myself. A highwayman and a lass, and a toff who was really the villain, and a first-rate murder and a duel, and everything going horribly wrong before turning out right in the end—those were the plays for me. Or the ones that made you shriek out loud, with blue demons dancing, and red demons rising up, and the Devil disappearing with a BANGthrough a hole in the floor. This particular night—the night I’m telling you about—it was a play about two Corsican brothers. The one gets foully murdered by a villainous French toff, and of course the other has to take revenge. It was the first time I’d seen it, so naturally I had to watch it close.

“This is wrong.”

A voice in my ear.

“What?”

“These are bad places.”

It was him—the Printer’s Devil. He was right behind me in the crowd.

“I shouldn’t be here, I shouldn’t have come, and neither should you, such places lead us into wickedness.”

He spoke like that, a low worried voice and the words all spilling out on top of each other. He was staring at the stage like it offended him so much he just couldn’t look away from it for a second. I was familiar with that look, from all the times it was directed at me, by gentlemen with high moral principles and low filthy longings. This one was no gentleman, and of course he was just a boy, sixteen maybe, although he was tall for his age. A lot taller than me.

“You’re gay, ent you?” he asked.

“Never you mind what I am.”

“You’re gay, you’re a whore, you’re here to flaunt yourself and have carnal connection.”

“I’m here to watch the play. So fuck off.”

He was right, though—the part about me being a whore. Why deny it? There was lots of us gay girls here—dozens of us, just like every night—and most of ’em had come for the business. At the big music halls, the ones where four thousand punters could crowd in, there might be two hundred girls at work, and private rooms behind the boxes, where a gentleman could retire for half an hour with a girl and a bottle of wine. There were no little rooms at theatres like the Kemp—it wasn’t grand enough for that. But there was the night houses across the way, and alleyways behind, where the world could go round as the world has gone round since Adam met Eve, and will continue doing till Judgement Day comes. But me personally, I was here to watch the play. Besides, there was something just a little bit wrong with this one, the Printer’s Devil with his gabbling worried voice. You get so you can sense it straight off, the ones you’d better steer clear of. So I edged forward, through the crowd.

We were way up top, of course, cos that’s where you’d go for a sixpence. The theatre was packed, like usual, and I’d come in too late to get a seat on the benches, which left me standing at the back. The pit was a shilling, and them who could afford three shillings were in the boxes—merchants and such and the real titled gents and ladies—though they steered pretty much clear of theatres like this. Up here it was tradesmen and shop-girls and apprentices and dollymops, and all manner of riff-raff like myself, crammed in cheek-to-giblets and craning to see round someone’s hat. The smell was what you’d imagine, all mixed in with gunpowder from the explosions and oranges being eaten by the crowd, and the heat was terrible, from all the bodies and the gaslights. But the play was prime.

It had just got to the part where the ghost of the one brother appears to the other, all quavery and beyond-the-grave with his hair standing straight up on end, and blood and gore on his breast from the sword that foully struck him down. There were gasps at the sight of him, and shouts to his brother of, “hear him, hear him!” and “it was the Frenchman done this!”—you know, in case he wasn’t clear on who he should be killing for revenge. For they were enjoying this, and not jeering as they do when the play’s no good, although they weren’t impressed with the actor who was playing the Frenchman’s friend, and there’d been a few orange peels flung at him already.

“They incite the passions, that’s what they do, they stir up our animal spirits, such low and lewd entertainments.”

Fucksake. He’d come up behind me again, talking low and faster than ever.

“The door is open, just a crack but that’s all he needs, the door is open and the Devil slips in. That’s why it’s wrong, I shouldn’t be here, I should leave.”

“Then go.”

“I want you to come with me. I want you to come right now.”

“What for?”

But of course I knew what for. He was pushed up against me in the press of bodies and I could feel it, sticking into my back.

“Christ, would you take that bloody thing—?”

“No, not for that!”

The look on his phiz was pure distress—enough to make you laugh out loud. Cos of course I had him pegged from the first second he started gabbling. One of them bible-thumpers so horrified by the goings-on in his breeches that he torments himself barmy. Suddenly—Gawd help us—he was Bearing Witness. Something about being a norrible sinner and in the Devil’s clutches till he was Saved by the Light and it was someone called the Captain who rescued him.

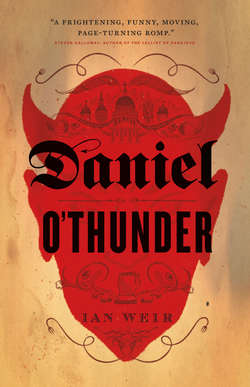

“The Cap’n loves me, he said ‘I love you Young Joe like a son.’ He said so this very morning and I could of wept with happiness. And I dreamt one time of how the Devil come for me, but the Cap’n was there to stop him. He seized the Devil by the nose, the Cap’n did, and thrashed him with a stick, Cap’n Daniel O’Thunder!”

The name meant fuck all to me, and besides I’d had enough of this. Now he was clutching my arm to keep me from getting away.

“I swear, he thrashed the Devil till he howled, and—argh!”

What you do is, you stamp down hard with the sharp heel of your boot on his instep. It works a treat if you do it right, and I’d had plenty of practice, trust me. With a shriek he lurched back into the punters behind him, who didn’t like this one bit, and let him know it. I slipped through the bodies, quick and nimble, for I can flit like a swallow when needs be. When I looked back I seen his face for just an instant, twisted and clenched, and then he was swallowed up in the crowd.

So I forgot about him, and watched the rest of the play. It was very satisfactory. The French villain who killed the first Corsican brother tried to flee in his carriage, but crashed in a forest. He was with his friend—the friend being another Frenchman, tricked out in a great black wig and the worst stage whiskers I ever seen. He couldn’t act a lick to save his soul, this friend, but it was a small part so it didn’t matter so much. Anyroad, the second Corsican brother stepped through the trees and challenged the villain to a duel. There was a great sword-fight and the villain fell dying in agony and at the very end the ghost appeared again to talk to his brother. Both brothers were played by the same actor, a wonderful trick that must have been done with mirrors, and you should have heard the shouts and applause. After the play there was an acrobat, and then the burlesque, and it was nearly midnight when it was finished. You tell me where else you’d find yourself an evening like that for a sixpence, because you wouldn’t. You wouldn’t find it for a pound.

And if I’d seen my mother on that stage, it would have been perfect. I was watching for her, of course, like I always did. But, just like always, it turned out she was somewhere else.

THE NIGHT AIR was cold, coming out of the theatre, and Christ the noise and jostle. The street out front was clattering with coaches, looming at you out of the fog—cos what else would there be except fog, on a London night? Yellow fog in the gas-lamps, waiting to swallow us, and rivers of Londoners flowing in all directions. That was London, all hours. Just slip into the current and let it carry you away, like a tiny lump of something—don’t ask what—bobbing along on the Thames.

Just before it carried me round the corner, I seen the Printer’s Devil again. He was standing under a gas-lamp clutching his tracts. Someone had stopped to take one—a tall old gentleman in a queer old-fashioned black coat and boots and a slouchy low-brimmed hat. The gentleman was standing very close, looming over him like a hawk on a tree branch. I only seen them for a second, and it was hard to be sure with the fog, but it seemed to me like the gentleman was saying something. The Printer’s Devil was shrinking back with his eyes wide and white, like a horse’s when a fist is raised to strike.

That’s when the gentleman looked across and seen me. Just an instant. His face beneath the low-brimmed hat, staring at me from out of the fog, like something coiled up in a cave.

I WAS A NGLING SOUTH and west towards the Haymarket, so the route took me along the edges of the old rookery of St Giles. The Holy Land itself—the biggest and worst of all the London slums.

It wasn’t like it was in the old days, or so I’d been told. In the old days the Holy Land was one great maze of tiny stinking streets and blind alleyways, stretching from Drury Lane west to Charing Cross Road, and from Great Russell Street in the north all the way to Long Acre. You could stumble in and not come out again, not ever—just wander lost till someone took pity and slit your throat. A lot of it had been torn down, but parts of it remained. Houses so rickety you’d think the next big wind would blow them over, all jumbled together so close that one couldn’t fall without taking a hundred more with it. Broken windows patched up with rags and paper, with poles sticking out for hanging clothes, and slops being emptied look-out-below. In the old days there was paths through the Holy Land that never saw the light of day—you could go from one end to the other through windows and cellars. This was wonderful handy for thieves and footpads, for how was the Watch to follow? Nip in and just disappear, like a rabbit in a field of brambles. There were still routes like this, if you knew where to look—and I did, since the Holy Land is where I’d lived with Mrs Dalrymple.

But I wasn’t deep into the rookery that night, just on the very fringes. The roads beyond were still crowded and busy, but here it was just filthy and quiet. Dark too, and choked with fog, for who’d waste good gaslight on a shit-hole like St Giles?

That’s when I knew someone was following me.

I looked quickly round, but of course there was no one there.

“Hello?”

Nothing.

I started forward again, and tried to tell myself I was just being a fool, and frightening myself with imaginings. But I was moving fast, now. This was London, and you knew the risk you took. There were gangs who roamed these streets at night, looking for a girl on her own, to rob and do things to and leave half dead. There was eyes watching from alleyways, belonging to God knows who. And if you were really unlucky, there was the London Burkers. Luna Queerendo laughed at this, but Luna was a twat. God forgive me for saying that, but she was, no matter what happened to her afterwards.

The London Burkers were a gang of murderers. They crept about in the London fog slitting throats and selling the corpses to medical students, who wanted them for cutting up and studying. When Luna heard me mention this, she gave that laugh of hers— hooting like an owl, all smug—and said the last of the London Burkers was hung at Newgate twenty years ago, which everybody knew except for poor Nell apparently. And anyway the law’d been changed so medical students could get their corpses other ways, poor Nell she’s such a daisy isn’t she, hoot-hoot-hoot.

Twat.

Besides, there was worse than the London Burkers. There was Spring-Heeled Jack. I knew for a fact he was out there, cos everyone knew about Spring-Heeled Jack. I knew someone once who actually seen him. She nearly died. He jumped up from behind a wall—jumped twenty feet into the air—with his eyes burning and two horns on his head. Except you couldn’t think that way. You couldn’t slink about scared all the time, cos then you couldn’t live a life at all.

I’d been listening to my own footsteps echoing on the cobblestones: one-two-one-two. And then I heard the others: muffled and uneven. They stopped, half a second after I did. But I’d heard them, behind me.

Clip-clop.

I stood very still.

“Who the fuck is there?”

Silence and fog, growing thicker by the second. A deadly chill creeping over the cobbles.

“You better know, I got a knife. I know how to use it. You don’t believe me? Then try.”

Fog like a living thing, moving.

There. Something moving that wasn’t fog.

I ran for my life, with him behind me—whoever it was. I slipped, and almost fell, and every second I expected to feel hot breath on the back of my neck, and hands laying hold. But I was fast, and he wouldn’t catch me. I knew these streets—I knew where I was going. Except I’d turned the wrong way, or this was the wrong street, cos it was a dead end. In front of me was a wall of brick.

The yellow glare of a bull’s-eye lantern came lurching at me out of the fog. There was a face. I screamed.

“Good God!” he exclaimed.

A chalk-white face with the eyes black and horrible. “Christ, you startled me! No, it’s all right. Look, I’m sorry. I think I got turned around—bit lost—the fog and these damned winding . . . Look, I really wish you wouldn’t wave that thing in my face.”

Cos I had the knife in both hands, never mind how both of them was shaking. “You bastard—keep away!”

“Yes—fine. Look, I’m not going to hurt you . . .”

The two of us, in the yellow pool of light from the bull’s-eye. I’d seen him before—I was suddenly sure of that. But where?

“Stop following me!”

“Following you? How could I be following you? I was coming the other way. I was back there—whichever way it was. I was coming from the theatre, and now I’m completely turned around.”

The Kemp Theatre. The black around his eyes was make-up. That was where I’d seen him. He stood uncertainly, the lantern rocking in his hand.

“Look, I’m sorry if I frightened you, but look here, could you please stop—Christ!”

He broke off with a shout of pain. He’d put his other hand out, and this startled me, which was too bad for him, cos I was still very twitchy—even though I recognized him now.

“You’re him. You’re that French turd.”

“Look what you’ve done! What did you do that for? You’ve sliced my hand to the bone!

“Not the first turd—the other one. You’re the French turd’s friend. From the bloody play.”

I was so relieved I started to laugh. He was shorter without his high-heeled shoes, and of course his face was different, without the black wig and glued-on whiskers. But it was him, all right. Now he was clutching his hand and tottering back, staring at me all shock and disbelief. You’d think I’d just run him through the heart.

“Fucksake, it’s a nick. Look at you, a grown man, carrying on. Besides, it’s your own fault, cos you startled me—so don’t go blaming me, I fucking hate that. And mister? Maybe this ent the time, but someone’s got to tell you the truth. You just can’t act for dogshit.”

PEOPLE CLAIMED Mother Clatterballock had been a famous beauty in her day, with men from all over London queuing up with guineas in their hand. Hard to believe, but looking back I suppose it makes sense. It would explain how she’d managed to earn the money in the first place, to set herself up in business— that and a great grasping fist, and a nose that could sniff out an advantage like a bloodhound, and an ear that could hear a farthing drop onto a feather bolster half a parish away. Now she was twenty stone poured into a purple velvet dress, with a great braying laugh and a nose like a potato and her bosoms billowing up from her bodice like two great wobbling blancmanges. But she had her charm, when she wanted to use it—give the old girl her due—and she was decent enough to me, more or less, much of the time. So you take the bad with the good, and get on with your business, don’t you?

Mother C kept a house in Panton Street, across from a dance hall and wedged between a hot baths and Dalley’s Oyster Rooms. Two floors up rickety stairs there was rooms for the girls, and down below was the night house. It was like any such house, with wooden benches and trestle tables all crammed in, and piss-smelling sawdust, where you could get a drink and a meal at all hours, providing you weren’t too particular. There was always a few sporting gentlemen, meaning gamblers and swells and layabouts, mixed in with a regular working man or two and maybe a table of law students out on a spree. And of course them as come creeping out of their holes after dark. Thieves of all manner, for thieves came in every category you could imagine, and they all had names. Burglars and sneaks and dog-thieves. Cracksmen who specialized in breaking locks, rampsmen who specialized in breaking heads, and bug-hunters who preyed on them as was staggering drunk. Swindlers and card-cheats and sharpers, and hard men talking flash, and girls from the Haymarket. There was a painting of Tom Cribb on the wall, who was once champion prize-fighter of all England, and a story that the great man once raised a glass here years ago, long before Mother C ever came. People said he danced a sailor’s hornpipe on top of a table, though whether there’s truth in that I couldn’t say. Another time a man come in and emptied an entire sack of rats out onto the floor. I can tell you that was true, cos I was here the night it happened, and Lord you should have seen it. A hundred people in a room thirty foot by twenty, shrieking and yelling and brown sewer rats running everywhere and biting. I’m not sure why the man done it. He was a sporting gentleman.

I was hardly through the door before old Lushing Mary spotted me. She came screeching like a seagull.

“Where did you get to? Where? I was frantic!”

I rolled my eyes a bit, and reassured her. “I’m fine, Mary. I went out, but now I’m back again, ent I? Back again safe and sound.”

“And what if you weren’t? What if you were floating in the river right now? Or face down with your windpipe slit like a chicken’s, you selfish little slut! For then just think what would happen to me!”

It was a fair enough point. I wasn’t supposed to go out at all, except when I had Mary with me. This was the arrangement for all the girls who lived at Mother Clatterballock’s, and such places. Mother C couldn’t have a girl sneaking off to do her business and pocketing all the coin for herself, or perhaps sneaking off and never coming back at all, wearing clothes on her back that belonged to Mother C, since she provided the dresses we wore. So when a girl went out, she had an old lady with her, and mine was Lushing Mary.

I slipped off fairly regular, of course, whenever Mary was in her cups or turned the other way. Mother C knew about it, too, but she didn’t make too much of a fuss, cos she trusted me, as far as she ever trusted anybody. Or at least she was willing to take a chance where I was concerned, after first explaining what would happen to me if I ever tried to sneak away from her. Explaining very carefully, and in specific detail. Besides, Mother C done well out of me—selling me for a virgin every night for three weeks running, when I first turned twelve and was old enough. It’s an easy enough trick, with a bit of acting and a few drops of sheep’s blood. She’d done well enough from me ever since, seeing as I had a bright eye and a fine set of teeth—every one of them still in my head.

“I’d be in the park—that’s where I’d be, if something happened to you!” cried Mary. “You want me to end my days in the park? God save us, the girl’s a monster—she’s got no feelings at all. An old woman in the park, reduced to all manner of depravity!”

When gay girls got too old and lost their charms, they had to find another way to scrape their living together. Some of them, like Mary, managed to get themselves kept on at houses like this, cleaning up in the daytime, and at night minding one of the girls. In return, they’d get a roof to sleep under, and food to eat, and enough gin to keep them limping through another day. If Mary lost her position, then where else would she go? Except down to the river to drown herself, or else to the park, like she said? And the river was the cleaner of the two, for all the stench and the shit floating down, pumped in from every sewer in London.

You could see the women in Hyde Park every night, as soon as it was dark. The old ones who couldn’t show their faces in the gaslight, no matter how heavy they painted. They’d creep about like crows, and in the end they’d be just a bundle of rags a-laying on the ground, to be discovered when the sun come up and carted off like all the bundles of rags before them. But till then they’d sell themselves for pennies to men who wanted things they couldn’t get from anyone else. Things you couldn’t even think of without your stomach turning. Things you’d die before you’d ever do, except here you were in the park, doing them.

“Come on, now, don’t cry,” I said. My arm around her shoulder, giving her a squeeze, cos she was working herself into a state. “We’ll get you something to drink. For Christ’s sake, buy her a glass of daffy—it’s the least you can do.”

“The least I can do? Jesus wept!”

This being my actor gentleman.

“Who’s the injured party, here?” he demanded. “I’m the injured party!”

“And I gave you my handkerchief to wrap it with, didn’t I? A brand-new handkerchief, practically new, and now it’s ruint— got blood all over. So stop moaning and buy a lady a fucking drink.”

He was cradling the hand in his lap, like it was a kitten that got run over in the street. Milking this for every last drop, and being most wonderfully wounded and aggrieved. A bit dramatic, was my actor gentleman. He would surely have been even worse if he hadn’t also been hunkering himself down in the darkest corner of the room, and hoping that Mother C’s fine customers would fail to notice him. But they did, of course, and were currently eyeing him pretty much exactly the way you’d expect: which is to say, like a pack of wolves noticing a piglet.

“I shouldn’t be here,” he muttered, out the side of his mouth. “I just wanted to see you home safely. And now I’m liable to end up floating in the Thames. Christ, no good deed goes unpunished.”

He tried a rough little laugh as he said it, like a man accustomed to risking his life as if ’twere nothing at all. Like I said: dramatic. Give him a cloak and a French accent, and he’d be the Count of Monte Cristo.

“He’s an actor,” I said to Mary.

He essayed another rough laugh. “But not, apparently, a particularly good one.”

“Dogshit,” I agreed, with a shrug. “Sorry.”

“An actor. D’you act in Shakespeare?”

This was Old Mary. She’d stopped her blubbering once the glass of daffy was in her hand, for being alive is never so bad if there’s gin to take the edges off. Now she actually perked up.

“I approve of Shakespeare.” She was sitting up a little straighter on the bench—as straight as she could manage, with a back bowed like a question-mark—and God save us if there wasn’t a spark in her eye. “My father was a schoolmaster, you know.”

I’d heard her say that before. I’d also heard her say her father was a Member of Parliament, or else a vicar. This last was something you’d hear an astonishing amount, with gay girls. On any given night, the dens and night houses of London was apparently chock full of vicars’ daughters, all painted and flat on their backs. How much of this was true I couldn’t say, though I certainly had my suspicions. If I had to guess about Mary, I’d guess she wasn’t sure herself, any more. But I’d actually seen her reading books. I’d even given her a book once, and told her it was for her birthday, though God only knew when her birthday was. It was a book of poems, with a cover of dark green pebbled leather. I wrote her name inside—to my friend Mary Bartram, on her birthday—and she grew all grave and said it was a treasure. She didn’t speak like she come from the streets, either, or from the servants’ quarters of some dirty provincial town. She spoke like someone who’d had an education, even after all these years, and falling all this long way down—all the way down to Mother Clatterballock’s, gulping her gin and holding on by her fingertips, with nothing but Hyde Park beneath her. There was a thought to cheer you up, wasn’t it? To comfort you about the ways of the world, and give you hope.

Often I heard Old Mary, when dawn finally came and the house was quiet, sobbing herself to sleep. I did that sometimes too, of course. But I was quiet as a mouse, and you’d never have known.

“That’s him!”

A woman’s screech, and my actor gentleman went rigid.

“That’s the one! Him right there!”

It was Luna Queerendo. She’d come in a minute ago, and now there she was with Mother Clatterballock, rearing up like an angry stick-bug. She was long and skinny, was Luna, with a little head wobbling on a long stick-bug neck, and a great long nose for looking down at you, and long bony fingers like Death himself in an old painting, and one of them was pointing straight at my actor.

Mother C peered through the haze of smoke, and saw. “Tim!” she called, in a voice like doom.

There was a stirring across the room, and Tim Diggory raised his awful head.

Tim was the bully here, which is to say he made sure gentlemen took no liberties but the ones they paid for. He was six and a half foot tall, with a chimney-pot hat on top of it, and a lantern jaw that worked from side to side when he was trying to get his thoughts round an idea, for Tim weren’t swift. Not even to begin with, and that was before a hand with a cosh in it had reached out from a drunken brawl one night. It laid Tim out twitching, and he never rose again for three days. He finally got up, but the cosh had broken something crucial, some kind of spring deep inside the brainpan, and Tim was never quite right again—even by Tim’s standards.

Now he came looming up behind Luna, who had that finger in my actor gentleman’s face. He was shrunk back against the wall like the last rat left alive in the rat-killing ring.

“He never pays for his drink last time, the shitsack! He never pays for me neither! He pulls it out, I reaches for the basin, and he’s gone—out the door and down the stairs, still hoisting his breeches up over his spindly erse!”

Tim Diggory fixed his left eye upon my actor gentleman. His right eye drifted across the room. Tim’s eyes always looked in different directions, and the left eye—the one he used for fixing upon you—was changeable. Sometimes it was sleepy, like a child’s. On those occasions there might even be a little smile on Tim’s lips, like he’d just remembered something that used to make him happy. But then without warning his eye would go all narrow, and flash like a telescope on a hill. When that happened, God help somebody—which God never did of course, either because he didn’t care to look round in places such as Tim Diggory was to be found, or else because God was no fool, and lay low like everyone else when Tim’s left eye went flash.

It was flashing right now.

“No, look, I’m sorry,” my actor gentleman was stammering. “I’m terribly sorry, but there’s been a misunderstanding. I’ve never been here in my life.”

“Fuck you ent been here!” cried Luna.

“All right, then I was—you’re quite right about that, ha ha—but I paid—I did—I left the money on my way out—at least I thought I did. Ha ha ha. There’s clearly been some mistake, and—”

“There’s been a mistake indeed,” Mother Clatterballock wheezed, for she’d put herself out of breath hauling her bulk across the room, “and you’re the one who’s made it.” She held out a great grubby hand. “Two pound.”

“Two pounds?”

“A pound for Loo, five shillings for the drink, five shillings for putting me out of temper, and ten shillings for the hinsult to the hestablishment. Plus the collection fee and something for Tim—better round it out to two guineas. Payable instanter.”

I laughed out loud.

“Oh, come on. Luna was never worth a pound on the best day in her life—and God knows that day came and went.”

“You shut your pie-hole, Nell Rooney!” cried Luna. “I’m worth more than you’ll ever be, with your pinched little phiz like a weasel. And my name isn’t Luna, you little scrawny slut, it’s Louise!”

Matter of fact, this was true. Her real name was Louise Maggs. I started calling her Luna Queerendo after finding out she’d been married once. The marriage happened years earlier, when some poor wealthy gentleman actually fell in love with her, and him with three thousand pounds a year. Well, this was the magical pot of gold she’d been dreaming of all her stick-bug life. But when the gentleman’s family found out they got themselves a writ—de lunatico inquirendo, which meant some magistrate had to judge whether he was soft in the head. Sure enough, guess what? That was the marriage annulled, and the pot of gold snatched back again, which would have been very sad I suppose if I hadn’t hated her. And of course I felt bad as anything about what happened to her in the end. I wouldn’t have wished that on any living creature in this world.

“I don’t have two guineas!” my actor gentleman was stammering. “Dear God, where would I get hold of two guineas? Look, here’s what I’ve got. I’ve got a shilling—that’s all the money I have, I swear. But you can have it. It’s yours, with my very best wishes. And I won’t come back. At least, I will come back—yes—I’ll come back directly, with the rest of the money. All right? You just wait here.”

He looked from Luna to Mother C to Tim, all charming and desperate, like a piglet hoping these wolves might like vegetables instead. There was silence.

“It’s the cheek of it,” said Mother Clatterballock. “That’s what stuns you. The sheer gall.” She looked to Tim Diggory, like a magistrate about to reach for the black cap. “Tim? I don’t believe I want to see this one again.”

“No, listen to me. Wait—please—!”

My actor gentleman’s voice was sounding strangled, but nowhere near as strangled as it was about to be, cos Tim Diggory was already reaching out to take him by the throat.

“Oh, leave him be, for Christ’s sake. I’ll pay what he owes.”

“You?” Mother C shifted to stare at me. “Cos why?”

“Cos he’s my brother.”

Even Tim stopped.

I’m still not sure why I said it. It’s not as if I liked him, even. Probably it was just me being contrary.

“And it’s not two guineas, it’s ten shillings. Three for the drink, two for the trouble, and five for Luna—which is at least three shillings on the generous side, where’s she’s concerned.”

That was the other reason I spoke up. I couldn’t stomach the smarmy sneer on Luna’s face, with her supposing anyone could value her at a pound.

“Don’t you have a doll to go play with?” Luna flung back after sputtering for a bit, this being her best go at deadly sarcastic wit.

Mother C wasn’t listening. Her eyes were fixed on the guinea I had fetched out of my pocket.

“You can take it out of this,” I said, very casual. “I was give it by a gentleman I met this afternoon—a real gentleman, with a carriage, who liked what he saw, and knows you have to pay top price for quality.”

This was God’s own truth, or some of it at least. I was never a beauty, but I was small, and there are gentlemen who like that. This one wanted a naughty child that required correction, so that’s what I gave him. I was a naughty child that stole things too.

“Oh, you peach,” wheezed Mother C, and had the guinea before I could think twice. “Is this my clever girl? Oh, my.”

I’d never see that guinea again, nor any part of it. But the expression on Luna’s gob almost made me forgive myself. Besides, I still had the gentleman’s gold watch, which was in his weskit when the gentleman wasn’t. It was worth a good sight more than a guinea, and Mother C was never going to know about that. Anyroad it was always a good investment to stay Mother Clatterballock’s peach. Then there weren’t so many questions about coming and going as I pleased.

“Your brother, eh?” Mother C was eyeing my actor gentleman. “And ’as ’e come to rescue his little Nell from out o’ this life?” She said it with her old whore’s squint, the one that said both I’m just having a joke with you, ducks, and think very careful what you say next.

“No,” I said, “he’s here to ask money of me. For there has to be one in each family that’ll do a day’s work, and he ent it.”

I don’t suppose I fooled her one bit. But after a moment, Mother C’s squint relaxed into a leer. “Well, then, enjoy your family time,” she said, “for this hestablishment is built on family walues. At least, enjoy yourselves for a minute or two. But after three minutes, I’d best see you back at work, Nell, for the sake of all concerned. And you, sir,” she added, with another look at my actor, “won’t be showing your phiz ’ere again without you got coin of the realm clinking in your pocket, family or no family, brother or no brother, for Tim Diggory is here seven days o’ the week, every week o’ the year, and that hincludes Christmas. Ent that right, Tim? Yes it is. So nod your ’ead, Tim, and let go the gemmun’s windpipe, and we’ll take our leave—and so will the gemmun. ’E’ll be on his way directly, and won’t be ’anging about like a fartleberry from an arsehole. Come on then, Loo. Loo! I’m talking to you, you surly slut. Pinch your cheeks all rosy-nice, and smile for the lads, for no one wants to fuck a lemon.”

So they left, with Luna shooting unspeakable looks every second step. That left me and my actor gentleman, staring at each other.

“Yer welcome,” I said.

“Yes. God, yes. Thank you.”

He sat with a whump on the bench, like his legs had clean give way beneath him. I matched the saving of his hide against that guinea of mine in Mother C’s fat grubby palm. Good exchange, Nell, I said to myself, you twat.

“I’ll pay you back, of course.”

“Yes you bloody well will. You’ll pay me back with fucking interest. By the time you’ve finished paying back, you’ll wish you’d gone to the moneylenders instead.”

He started to laugh, with the sheer relief of it. He was actually nice looking, when he laughed. In fact, he was almost handsome— or at least he would’ve been if he’d had a bit more in the way of a chin. All that Count of Monte Cristo business—the brooding stranger, rough and bitter—that was nothing but an act he tried to put on. But just when you were fed to the teeth with him, he’d cock his head a quarter of an inch, and sneak a peek at you out from under the wing of soft brown hair that had fallen over his eyes, as if to ask: how am I doing so far? Then he’d flip it back with a movement of his hand, and give a crooked boyish smile. A rake’s younger brother, maybe—wishing he could be dangerous and wicked, but not getting much past coy.

Maybe I didn’t dislike him as much as I’d thought.

“My name is Hartright,” he said. “Jack Hartright. At least, this is the name I go by, in these days of my exile from a former life.”

“Then go buy me another drink, Jack Hartright, just before you fuck off. Cos your three minutes are about up.”

He laughed again, and shook his head. He had a scar at the side of one eye—a strange thing to see on such a smooth face. It was shaped like a horseshoe.

“My God, but you’re a curious little creature, aren’t you?”

There was several things I could have said to this, and probably would have, in another half a second. Starting with: “Tim Diggory? Come back here please, cos I’ve decided I’d like you to kill him after all.” But I didn’t get the chance.

“I’ll be glad to buy you a drink,” he said.

Except it wasn’t Jack Hartright who said it.

Tall and thin and dressed in black, with a limp and high boots and a low slouching hat. The old gentleman from outside the theatre. He’d come in behind me, without my knowing he was there.

He’d brought the night in with him; suddenly the air was cold.

“What would you like to drink, my dear?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Thank you very kindly, but I ent available.”

“No? But I think you are.”

He had a coin in his hand. He’d plucked it out of the air, some fucking conjurer’s trick.

“I’ll pay you a crown.”

It was good money—except you always knew, when it was wrong. In the first second, you just knew, before they said a word. But this was different. This was all wrong, but wrong in a way I’d never come up against before. I opened my mouth to call for Tim Diggory.

“A guinea,” I heard myself saying instead.

His lip crept up over his teeth. I suppose you’d call it a smile.

I STOOD BY the window. My room was at the top of the stairs, on the third floor, at the back. There was a bed, and a little low table with a pitcher and a basin and a candle fluttering, and a trunk against the wall by the door. He looked round the room. He looked at the trunk. Then he sat down on the lid of it, slow and creaking, and looked at me.

The room was icy with him.

“Let’s have the guinea, then,” I said.

All my things were in that trunk he was sitting on. Everything I owned. Bits of clothes, and other things too—most of them useless, but they were mine. An old clock with some of the insides missing, except maybe I’d meet someone who could mend it. A wooden soldier with arms and legs that moved when you pulled a string. My hat with a feather and some lace and a real silk handkerchief. I had some books, too. One of them was lying on top of the trunk. He picked it up.

“You can read?”

“Of course I can bloody read.”

“Well done.”

It was a little book about Dick Turpin’s famous ride. I had some other books too, inside the trunk. One about Tom Thumb, and also Bewick’s Birds with beautiful drawings.

“My guinea,” I said. “You said a guinea, so let’s have it.”

He plucked it out of the air—that fucking conjuring trick of his—and smiled. “Here,” he said. He held it out, but only partway, so’s I’d have to step closer to take it. When I did, his other hand moved faster than I could see. I gave a cry and pulled back, thinking he was grabbing at my throat. But it was my locket he wanted—the one I had on a chain around my neck.

“Give that back!”

He turned it with his fingers, examining it in the candlelight.

“I mean it. Give it here. Look, it’s only brass, all right? It isn’t gold—it ent worth anything to you, so just give it here. Mister? Fucksake . . . !”

“What do I get,” he asked, “for my guinea?”

His eyes, pinning me. Narrow dark eyes, with flecks of colour in them. They didn’t blink. There was a smell about him, a strange smell of lavender water and something else, something dark and sharp. Sulphur?

“I expect you’d do almost anything I asked,” he said, musing. “A girl like you. For a guinea.”

“Then you’d be wrong, mister.”

“Would I?”

“Yes. You’d be expecting wrong.”

“But you’d do anything for five guineas, wouldn’t you?”

“Five?”

With five guineas in my hand I could leave this hole. With five guineas every week, I could be someone different completely. I could have my own rooms, and a servant. I could have a carriage. There were girls all over Mayfair, set up like ladies, cos they had a gentleman who would give them five guineas a week.

He smiled a little, as if he’d seen the thought cross my mind.

Oh, Christ—but not five guineas from this one. Not five hundred guineas, if it had to come from this one.

“What would you want,” I heard myself asking, “for five guineas?”

He mused for another minute. He was trying to pass for a younger man, maybe five-and-forty, but that was done with paints and dye. He was much older, but there was a ropey strength about him too.

“I think what I want most of all,” he said finally, “is for someone to die. Yes, I believe I’d like someone to die, for sheer love of me. For five guineas, would you do that?”

The window behind me was tiny. Even small as I am, I’d never squeeze through. To reach the door, I’d have to get past him, and he knew it.

“I think you’d best leave, now.”

“It’s only dying. Everyone does it, sooner or later. One way or another.”

“I’m warning you. If you don’t leave, I’ll shout for Tim Diggory.”

“You’d certainly die for ten guineas—because I’d give them to Mother Clatterballock. For ten guineas, she’d hand you over with her blessings. She’d applaud while the deed was done, and for an extra shilling she’d lay on refreshments.”

“Were you the one that followed me, tonight?”

It came in a cold flash. I remembered his footsteps on the stairs as he followed me up to the room. With a limp: clip-clop.

“Tim!”

But Tim was three long rickety flights below. Oh Christ, I thought, you’ve done it now. You’ve really done it, haven’t you, Nell? You’ve finally done it this time.

“God’s blood, you’re so much like her.”

He’d opened the locket, and was looking at the little picture inside. Something had shifted in his face.

“You truly are. You’re so much like your mother.”

This came so unexpected that I just stared at him.

“Her picture, in the locket. That’s your mother, isn’t it? Yes, I saw it in you straight away, outside the theatre. It’s not the features, exactly, but the expression. The eyes, and the set of the mouth. For a moment, I actually thought it was her, come back to me.”

I made a grab, and snatched my locket back. He was looking at me with the strangest expression.

“You never knew my mother.”

“I knew your mother well. I had her many times.”

“You’re a liar!”

“But not about this.”

I was trembling. From the cold of him, and more than that.

“Where is she, then? Tell me about her.” My voice was shaking now. “If you can tell me where she is, I’ll do what you want.”

But whatever he was going to say was lost in the ruckus that bust out suddenly from the next room. It had been brewing for a bit—a man’s voice, muttering, and a woman’s, rising. I’d hardly noticed, for obvious reasons. But suddenly it was shouts and crashes, and the man hollering that he’d been bit, and someone’s head being pounded against the wall, and the woman—it was Luna Queerendo; I’d know that voice anywhere—shrieking for Tim Diggory. Except she wasn’t shrieking for Tim, but shrieking at him.

“Take yer filthy—stop it! Oh please, for Christ’s sake—no!—you filthy—help! Murder! Murder!”

How it happened I don’t exactly know, but in the next second I was out the door and onto the landing. There was a great splintering as Luna crashed clear through the door of the next room, with Tim on top. More people were coming up the stairs, shouting for Tim to let her go. But none of it was going to help, for Tim was going to kill her.

He’d always been sweet on Luna, and followed her about— being just her type, since no one was softer in the head than Tim Diggory. He never quite worked up his nerve to touch, cos I think he actually had a notion that she might yet fall in love with him, even though she treated him like a dog. Besides he was terrified of Mother C, who warned him if he pestered the girls she’d have him gelded like a Clydesdale, and his onions stewed for oysters. But tonight, something had happened. I suppose he’d turned that eye on Luna—the one that flashed—and now all Hell had risen up inside. He had her by the hair with one hand, pinned down on the landing, and in half a second Luna was dead. Cos Tim was rearing over her and in his other hand he had a cudgel.

But the killing blow never fell. Tim went staggering forward and headfirst into the wall, so hard I swear the whole house shook. Someone had come thundering up the stairs behind, and slammed straight into him. It was a man with a shaggy head of yellow hair, and a great wide face, crying in a voice with an Irish lilt: “This won’t do, brother! No, brother—this won’t do at all!”

He had a spider’s legs, long and spindly—except they weren’t really, which I didn’t realize till afterwards. It was just that the body on top of them legs was so wide, a great barrel body and the arms of a blacksmith.

But Tim Diggory was even bigger. Tim had his cudgel too, and now both Tim’s eyes were wild. When the Irishman seen them eyes, he groaned.

“It’s the Devil!” cried the Irishman. “Aw, look at this poor man—it’s the Devil himself has risen up within. But we don’t despair—no, never that, no matter what. For when the Devil rises up, we cut him down to size again.”

Tim Diggory swung his cudgel in a blow that would dash the Irishman’s brains out. But the Irishman’s mauleys were raised, and he stepped inside the sweep of it. One, two—them mauleys landed on Tim’s ribs with a sound like pumpkins dropped from the roof to the cobbles.

“Forgive me, brother—and I hope you and I may yet be friends— but I will not abide the Devil.”

The next blow was flush on Tim’s jaw like chopping wood. Tim’s legs gave a wobble, and then down he went like an ox in a slaughteryard.

“And look how strong the Devil is still.”

Tim was struggling to rise to his knees again, grovelling for his cudgel. So the Irishman dropped onto his haunches, which put a stop to whatever the Devil had in mind, since the haunches were on Tim’s head.

The stairs were packed with gawkers now, peering and exclaiming, and trying to get a glimpse of what was going on through the bodies wedged in front. In the midst was two nice-dressed older women in grey cloaks and bonnets, fluttering wide-eyed with distress and making little strangled cooing sounds like doves. It crossed my mind to wonder what on earth they was doing in a place like this, but like all the rest I couldn’t take my eyes off the Irishman. His face was broad and ugly and red with breathing hard, with side-whiskers like hedges and a nose like a knob of gristle. But there was something about him that made you hold your breath and pray he’d look your way.

“That’s it!” shrieked Luna. “Now kill the bastard!” She was standing in the doorway, clutching bits of her dress to cover herself.

But the Irishman shook his head in sorrow, as Tim give off little muffled protests from underneath his hindquarters.

“Kill him? No, we’d never do such a thing as that, for he’s our own poor brother. We love him and we forgive him—not because he deserves it, but just because it’s in our power to do—exactly the same as our Lord forgives us, even though we none of us deserve it, not for a second. We don’t deserve from him anything at all, but he loves us still, the Lord Jesus, no matter what we do in return. And one day he’ll come back, and on that blessed day he’ll beat the Devil like a yellow dog.”

That voice of his—I’d never heard anything like it. The words soared out of him like birds. I thought: I could listen to this voice forever.

“Yes, Our Lord will beat the Devil till all the welkins are ringing with his howls. Then he’ll fling him down into the Pit and bar the doors, and that’ll be the Devil done for once and all. But until that great day dawns, brothers, the battle’s in our hands— brothers and sisters too, for we’re all battlers together, battling for the Lord. So when you see the Devil, you stand up to him, and twist his nose, and fetch him a clout to rattle his teeth, and let him know what he’s up against! For the Devil’s a great coward, brothers and sisters—he won’t stand against a healthy Christian. And now I’d like us to sing. We’ll raise our voices in a hymn together, and we’ll make this house resound with a gladsome noise—all of us singing lustily, including our brother here I’m sitting on, for he has gone quiet now and still, and I believe this to indicate that the peace of our Lord has come upon him at last.”

There was uneasy exclamations at this point. One of the Dove Ladies caught the Irishman’s eye and fluttered enough to indicate that Tim wasn’t still from the peace of God upon him. It was more that the Irishman’s hindquarters was upon him, and he was suffocating. So the Irishman got up instanter, with a sound of dismay. Mother Clatterballock arrived at last just in time to see this— Mother C having wheezed her way up three flights of stairs. She exclaimed, “Christ Jesus, ’e’s squashed Tim like a bug!” But a bit of brandy got Tim restored, and sitting up again, with all the wildness squashed right out of his eye. The Irishman looked relieved.

“Are you a madman, then? Or just a fool?”

It was the tall icy gentleman in black. He was standing behind me in the doorway to my room, staring at the Irishman. His smile was wintry and mocking, but there was something else too—like he’d seen the Irishman before, and was trying to place him. The Irishman seemed like he might be thinking the same thing in return, cos they neither of them moved for a moment or so, the way two fighting dogs will do when they meet by accident. Stiff-legged and bristling. Waiting to see if the other will lunge, or pass by.

“I am a man who goes here and there,” said the Irishman, “in the name of the Lord. If that makes me his fool, then it is my honour to be so.”

“And what does the Lord’s fool call himself?”

“My name is Captain Daniel O’Thunder. And who, brother, are you?”

The tall icy gentleman looked him slowly up and down again, the way an actor does on the stage, to show contempt.

“I am one who is beyond you,” he said. “Utterly.”

He put on his hat, and raised his lip, and shouldered through the press of gawkers. They all flinched back to let him pass.

“May the Lord bless you and keep you,” the Irishman called after him, “and mark you for his own forever.”

The tall icy gentleman looked back, and raised his lip again. Then he passed down the stairs—clip-clop—and was gone.